00043827 PRODOC Sabana Camaguey 3 Firmado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Day-By-Day Itinerary

Your Day-by-Day Itinerary With the long-awaited dawn of a new era of relations between the U.S. and Cuba, Grand Circle Foundation is proud to introduce a new 13-day journey revealing the sweep of this once-forbidden Caribbean island’s scenic landscapes, colonial charm, and cultural diversity. Witness the winding lanes of colonial gem Camaguey, the magic of Spanish- influenced Remedios—and the electricity of Havana, a vibrant city with a revolutionary past and a bright future. And immerse yourself in Cuban culture during stops at schools, homes, farms, and artist workshops— while dining in family-run paladares and casas particulares. Join us on this new People-to-People program and experience the wonders of Cuba on the brink of historic transformation. Day 1 Arrive Miami After arriving in Miami today and transferring to your hotel, meet with members of your group for a Welcome Briefing and what to expect for your charter flight to Camaguey tomorrow (Please note: No meals are included while you are in Miami). D2DHotelInfo Day 2 Camaguey This morning we fly to Camaguey, Cuba. Upon arrival, we’ll be met by our Cuban Trip Leader. Then, we begin a walking tour of Camaguey. Founded as a port town in 1514—and the sixth of Cuba’s original seven villas—within 14 years Camaguey was moved inland. The labyrinthine streets and narrow squares were originally meant to confuse marauding pirates (the notorious privateer Sir Henry Morgan once sacked Camaguey), and during our stay, we’ll view the city’s lovely mix of colonial homes and plazas in its well-preserved histori- cal center, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. -

Distribution, Abundance, and Status of Cuban Sandhill Cranes (Grus Canadensis Nesiotes)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250071729 Distribution, Abundance, and Status of Cuban Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis nesiotes) Article in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology · September 2010 DOI: 10.1676/09-174.1 CITATIONS READS 2 66 2 authors, including: Felipe Chavez-Ramirez Gulf Coast Bird Observatory 45 PUBLICATIONS 575 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Felipe Chavez-Ramirez on 09 January 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND STATUS OF CUBAN SANDHILL CRANES (GRUS CANADENSIS NESIOTES) XIOMARA GALVEZ AGUILERA1,3 AND FELIPE CHAVEZ-RAMIREZ2,4 Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 122(3):556–562, 2010 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND STATUS OF CUBAN SANDHILL CRANES (GRUS CANADENSIS NESIOTES) XIOMARA GALVEZ AGUILERA1,3 AND FELIPE CHAVEZ-RAMIREZ2,4 ABSTRACT.—We conducted the first country-wide survey between 1994 and 2002 to examine the distribution, abundance, and conservation status of Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis nesiotes) populations throughout Cuba. Ground or air surveys or both were conducted at all identified potential areas and locations previously reported in the literature. We define the current distribution as 10 separate localities in six provinces and the estimated total number of cranes at 526 individuals for the country. Two populations reported in the literature were no longer present and two localities not previously reported were discovered. The actual number of cranes at two localities was not possible to evaluate due to their rarity. Only four areas (Isle of Youth, Matanzas, Ciego de Avila, and Sancti Spiritus) each support more than 70 cranes. -

Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra De Cubitas

Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas 08 Rapid Biological Inventories : 08 Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas THE FIELD MUSEUM ograms 2496, USA Drive vation Pr – e 12.665.7433 5 3 r / Partial funding by Illinois 6060 , onmental & Conser .fieldmuseum.org/rbi 12.665.7430 F Medio Ambiente de Camagüey 3 T Chicago 1400 South Lake Shor www The Field Museum Envir Financiado po John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Instituciones Participantes / Participating Institutions The Field Museum Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba Centro de Investigaciones de Rapid Biological Inventories Rapid biological rapid inventories 08 Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas Luis M. Díaz,William S.Alverson, Adelaida Barreto Valdés, y/and TatzyanaWachter, editores/editors ABRIL/APRIL 2006 Instituciones Participantes /Participating Institutions The Field Museum Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba Centro de Investigaciones de Medio Ambiente de Camagüey LOS INFORMES DE LOS INVENTARIOS BIOLÓGICOS RÁPIDOS SON Cita sugerida/Suggested citation PUBLICADOS POR/RAPID BIOLOGICAL INVENTORIES REPORTS ARE Díaz, L., M., W. S. Alverson, A. Barreto V., y/ and T. Wachter. 2006. PUBLISHED BY: Cuba: Camagüey, Sierra de Cubitas. Rapid Biological Inventories Report 08. The Field Museum, Chicago. THE FIELD MUSEUM Environmental and Conservation Programs Créditos fotográficos/Photography credits 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Carátula / Cover: En la Sierra de Cubitas, hay una inusual frecuencia Chicago Illinois 60605-2496, USA del chipojo ceniciento (Chamaeleolis chamaeleonides, Iguanidae), T 312.665.7430, F 312.665.7433 tanto los adultos como los juveniles. Esta especie incluye en www.fieldmuseum.org su dieta gran cantidad de caracoles, que son muy comunes en las Editores/Editors rocas y los suelos calizos de la Sierra. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article Journal's Webpage in Redalyc.Org Scientific Information System Re

Cultivos Tropicales ISSN: 1819-4087 Ediciones INCA Benítez-Fernández, Bárbara; Crespo-Morales, Anaisa; Casanova, Caridad; Méndez-Bordón, Aliek; Hernández-Beltrán, Yaima; Ortiz- Pérez, Rodobaldo; Acosta-Roca, Rosa; Romero-Sarduy, María Isabel Impactos de la estrategia de género en el sector agropecuario, a través del Proyecto de Innovación Agropecuaria Local (PIAL) Cultivos Tropicales, vol. 42, no. 1, e04, 2021, January-March Ediciones INCA DOI: https://doi.org/10.1234/ct.v42i1.1578 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=193266707004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Cultivos Tropicales, 2021, vol. 42, no. 1, e04 enero-marzo ISSN impreso: 0258-5936 Ministerio de Educación Superior. Cuba ISSN digital: 1819-4087 Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas http://ediciones.inca.edu.cu Original article Impacts of the gender strategy in the agricultural sector, through the Local Agricultural Innovation Project (PIAL) Bárbara Benítez-Fernández1* Anaisa Crespo-Morales2 Caridad Casanova3 Aliek Méndez-Bordón4 Yaima Hernández-Beltrán5 Rodobaldo Ortiz-Pérez1 Rosa Acosta-Roca1 María Isabel Romero-Sarduy6 1Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), carretera San José-Tapaste, km 3½, Gaveta Postal 1, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba. CP 32 700 2Policlínico Docente “Pedro Borrás Astorga”, Calle Comandante Cruz # 70, La Palma, Pinar del Río, Cuba 3Universidad de Cienfuegos “Carlos Rafael Rodríguez”, carretera a Rodas, km 3 ½, Cuatro Caminos, Cienfuegos, Cuba 4Universidad Las Tunas, Centro Universitario Municipal “Jesús Menéndez”, calle 28 # 33, El Cenicero, El batey, Jesús Menéndez, Las Tunas, Cuba 5Universidad de Sancti Spíritus “José Martí Pérez”. -

Jardines Del Rey Ciego De Ávila

i Guide Jardines del Rey Ciego de Ávila FREE | 1 2 | | 3 |SUMMARY 7 WELCOME TO JARDINES DEL REY 10 CIEGO DE ÁVILA NATURE JEWEL 14 BEACHES 18 SAND DUNES 20 REEFS AND SEABED 22 CAYS 24 LAKES 26 TREKKING 30 JARDINES DE LAS REINA 31 MARINE ATTRACTIONS 33 DIVING 34 FISHING 36 NEARBY CITIES 39 PARKS, SQUARES AND MONUMENTS 44 OTHER INTERESTING PLACES 54 TRANSPORTATION 56 FESTIVITIES AND EVENTS | EDITORIAL BOARD PRESIDENTS: Janet Ayala, Ivis Fernández Peña, Annabel Fis Osbourne INFORMATION CHIEF: Juan Pardo & Luis Báez. EDITION: Tania Peña, Aurora Maspoch & Agnerys Sotolongo CORRECTION: Hortensia Torres & Sonia López DESIGN: Prensa Latina DISTRIBUTION: Pedro Beauballet PRINTING: Ediciones Caribe Year 2015 ISSN 1998-3166 NATIONAL OFFICE OF TOURIST INFORMATION Calle 28 No. 303 e/ 3ra. y 5ta. Miramar, Playa. La Habana. Tel: (53 7) 204 6635 E-mail: [email protected] 4 | | 5 Welcome to JARDINES DEL REY This archipelago takes up a 495 kilometers long strip toward the central-northern coast of Cuba and it´s the largest among the four ones surrounding the main island. One of its special characteristics is the imposing coral barrier that protects it, with almost 400 kilometers long, regarded among the major in the Caribbean, behind the Australian Great Coral Wall. It was Diego Velázquez —about 1513 and 1514— who christened the archipelago, located between the island of Cuba and the Old Channel of Bahamas, with this name, in honor of Fernando el Católico, king of Spain that time. Some chronicler asserted that he did such designating as a counterproposal of that of Christopher Columbus when he named the southern archipelago with the name of Jardines de la Reina, in honor of Her Majesty Queen Isabel of Castile. -

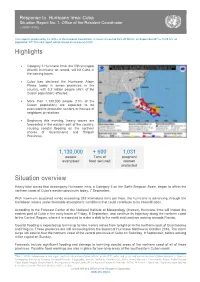

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

Un Pueblo De ¡Patria O Muerte!

“Lo imposible, es posible”. José Martí ÓRGANO DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO COMUNISTA DE CUBA / CAMAGÜEY, 21 DE SEPTIEMBRE DEL 2019 “AÑO 61 DE LA REVOLUCIÓN”. No. 40. AÑO LXI. 20 Ctvs. (ISSN 0864-0866). Cierre: 8:00 p.m. Un pueblo de ¡Patria o Muerte! El Buró Provincial del Partido extiende una afectuosa felicita- ción a los investigadores, es- pecialistas, funcionarios, técni- cos, y muy especialmente a los activistas y colaboradores del Sistema de Estudios Sociopo- líticos y de Opinión, en su ani- versario 52. Ustedes constitu- yen eslabón fundamental para que la dirección del país en todos los niveles ponga cada vez más, como ha llamado Raúl, “el oído en la tierra”. Las aspiraciones, las críticas, las sugerencias, el respaldo o el rechazo del pueblo ante cada proceso determinan la toma de decisiones, por lo que el histórico momento que vive nuestra Revolución reafirma la importancia de su labor cotidiana, a la cual sabemos continuarán dedicando su mayor esfuerzo, entusiasmo y responsabilidad. “Estamos trabajando distinto, pero con “¿Por qué renunciar a que los carros es- gía, deseos de hacer, ellos en pocos años los mismos principios de solidaridad, la- tatales recojan personas en las paradas; ocuparán nuestros cargos y ahora hay que boriosidad, con la misma voluntad y con- a que las panaderías y centros de elabo- aprovechar para que aprendan en tiempo vicción de victoria que caracteriza a los cu- ración tengan más de una fuente para la real esos cuadros del futuro”. banos”, expresó Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermú- cocción; a seguir desplazando -

Kids Stay Free Summer

KIDS STAY FREE ON YOUR SUMMER HOLIDAY 2020! KIDS STAY FREE TERMS AND CONDITIONS: The irst child under 12 years old will stay free of charge, sharing a standard double room with two adults. To take advantage of this offer, the child must be included in the booking. The following hotels offer free stays for children when you book between 9 September and 24 November 2019, for stays between 1 April 2020 and 31 October 2020. Don’t miss out! Book early HOTEL NAME CITY/COUNTRY KIDS STAY FREE MELIÁ VILLAITANA ALICANTE 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE SOL PELICANOS OCAS BENIDORM 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE MELIÁ BENIDORM BENIDORM 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE MELIÁ GRAND HERMITAGE BULGARIA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 11 YEARS GOES FREE SOL LUNA BAY RESORT BULGARIA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 11 YEARS GOES FREE SOL MARINA PALACE BULGARIA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 11 YEARS GOES FREE SOL NESSEBAR PALACE AI BULGARIA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 11 YEARS GOES FREE SOL NESSEBAR BAY AI BULGARIA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 11 YEARS GOES FREE SOL NESSEBAR MARE AI BULGARIA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 11 YEARS GOES FREE SOL SANCTI PETRI CADIZ 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE MELIÁ ATLANTERRA CADIZ 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE MELIÁ CALA D'OR CALA D´OR - MALLORCA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE SOL CALAS DE MALLORCA ALL INCLUSIVE CALAS DE MALLORCA - MALLORCA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE SOL MIRADOR DE CALAS CALAS DE MALLORCA - MALLORCA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE SOL CALA ANTENA CALAS DE MALLORCA - MALLORCA 1ST KID FROM 2 TO 12 YEARS GOES FREE MELIÁ CALVIA BEACH -

Cuba Birding Tour: Endemics and Culture in Paradise

CUBA BIRDING TOUR: ENDEMICS AND CULTURE IN PARADISE 01 – 12 MARCH 2022 01 – 12 MARCH 2023 Bee Hummingbird; the world’s smallest bird species (Daniel Orozco)! www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Cuba Birding Tour: Endemics and Culture in paradise The smallest bird on the planet, Bee Hummingbird, a myriad Cuban Todies and Cuban Trogons in every patch of scrub, and a host of other endemics and regional specials – all on an idyllic island paradise that is full of history and culture! Combining this 12-day Cuba tour with our Jamaica birdwatching tour provides opportunities to see almost 60 single-island endemics spread across two islands: Cuba, the largest of the Greater Antilles, and Jamaica, the smallest of the main islands in the group. Then you can also combine these tours with our Dominican Republic birding tour to see an endemic family (Palmchat) and further suite of endemics of another large (second only to Cuba in size) Caribbean Island, Hispaniola. In addition, on this Cuba birding holiday, we will have chances to find a number of multi-island endemics and regional specialties, some of which may, in the future, be upgraded in their taxonomic status. Cuban Tody is one of our main targets on this tour (photo William Price). This is a tour in which we aim to find all of Cuba’s realistic avian endemics, a host of wider Caribbean endemics, and finally a bunch of north American migrants (like a stack of brightly colored wood warblers), while also having time to snorkel during the heat of the day when not birding, to see the amazing architecture not only of Cuba’s capital but also of Camagüey and other towns, and of course to enjoy the old American cars and the general atmosphere of this tropical paradise. -

1.1. Área De Estudio Y Metodología General

GENERALIDADES 1.1. ÁREA DE ESTUDIO Y METODOLOGÍA GENERAL El Archipiélago de Sabana-Camagüey (ASC),conocido vegetales y animales, valores paisajísticos, arqueológi- también como Jardines del Rey, se extiende paralelo a cos y culturales. Esuna zona de gran importancia en los las costas de las provincias de Matanzas, Villa Clara, procesos biogeográficos relacionados con la diversidad Sancti Spíritus, Ciego de Ávila y Camagüey; desde la biológica en el Gran Caribe septentrional; sobresalen península de Hicacos, hasta la punta de Prácticos en entre ellos los eventos migratorios de varias especies la bahía de Nuevitas. Su longitud aproximada es de de aves, tortugas y peces (tiburones, túnidos, etc.), ade- 470 km, y está conformado por una hilera de cayos y más de albergar, metapoblaciones de arrecifes y pastos cayuelos, en grupos o aislados, que se asientan sobre marinos (Alcoladoet al., 2007). una plataforma común de poco fondo y están sepa- El ASC ha sido objeto de varias designaciones con rados entre sí por numerosos canales y canalizas, los fines conservacionistas. Por sus valores naturales y cuales permiten el acceso por mar a las costas de la grandes recursos de biodiversidad, fue declarado por isla de Cuba. Entre los cayos y la costa firme se forman el Ministerio de Ciencia Tecnología y Medio Ambiente extensas áreas de agua poco profundas denominadas de Cuba, como Área de Gran Prioridad para la Conser- bahías, entre ellas: la de Santa Clara, de Carahatas, vación. Fue reconocido por la Organización Marítima de Buena Vista, de Jigüey, de Gloria y de Nuevitas Internacional como Área Marina Sensible Protegida, se (CNNG, 2000). -

ANASTASIA VALECCE Assistant Professor of Spanish Dept

ANASTASIA VALECCE Assistant Professor of Spanish Dept. of World Languages and Literature, Box 719 450 Cosby Building Spelman College 350 Spelman Lane SW Atlanta, GA 30314 Tlf. (+1) 404 270 5542 [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION Spring 2013 PhD Emory University, Department of Spanish and Portuguese. Specialization: Latin American Studies with a focus on contemporary Spanish Caribbean, cinema, queer and gender studies, visual culture, performance, and literature. Dissertation Title: Cine y (r)evolución. El neorrealismo italiano en Cuba (1959-1969) [Cinema and (R )evolution. Italian Neorealism in Cuba (1959-1969)] Dissertation Committee: Dr. José Quiroga (Adviser), Dr. Maria Mercedes Carrión, Dr. Mark Sanders, Dr. Juan Carlos Rodríguez. 2006 Siena (Italy) M. A. “Università di Lettere e Filosofia”[University of Literature and Philosophy.] Specialization: Literary Translation and Text Editing from Spanish into Italian. Work as a translator, interpreter, and editor for Gorèe Press, Siena, Italy. Masters Thesis: Translation Project from Spanish into Italian of Mexican piece Yo soy Don Juan para servirle a usted [This is Don Juan Here to Serve You] by Mexican play writer Dante Medina. Thesis Adviser: Dr. Antonio Melis. 2004 Naples (Italy) B. A. “Istituto Universitario l’Orientale,” Foreign Languages and Literature (major in Spanish and English, minor in Portuguese). Honors Thesis: L’immigrazione sirio libanese in Argentina (1850-1950) [The Syrian and Lebanese Immigration to Argentina (1850-1950)] Thesis Adviser: Dr. Angelo Trento. AWARDS 2018 Spring Best Honors Thesis Award. Adviser for Honor thesis La Identidad Racial en la Sociedad Cubana: Una mirada a los Cubanos Afrodescendientes [Racial Identity In Cuban Society: An Overview of Afro Cubans], Spelman College.