Course Descriptions for German, Nordic, and Slavic Courses Taught in Literature in Translation Spring 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mind-Crafting: Anticipatory Critique of Transhumanist Mind-Uploading in German High Modernist Novels Nathan Jensen Bates a Disse

Mind-Crafting: Anticipatory Critique of Transhumanist Mind-Uploading in German High Modernist Novels Nathan Jensen Bates A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Richard Block, Chair Sabine Wilke Ellwood Wiggins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2018 Nathan Jensen Bates University of Washington Abstract Mind-Crafting: Anticipatory Critique of Transhumanist Mind-Uploading in German High Modernist Novels Nathan Jensen Bates Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Richard Block Germanics This dissertation explores the question of how German modernist novels anticipate and critique the transhumanist theory of mind-uploading in an attempt to avert binary thinking. German modernist novels simulate the mind and expose the indistinct limits of that simulation. Simulation is understood in this study as defined by Jean Baudrillard in Simulacra and Simulation. The novels discussed in this work include Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg; Hermann Broch’s Die Schlafwandler; Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz: Die Geschichte von Franz Biberkopf; and, in the conclusion, Irmgard Keun’s Das Kunstseidene Mädchen is offered as a field of future inquiry. These primary sources disclose at least three aspects of the mind that are resistant to discrete articulation; that is, the uploading or extraction of the mind into a foreign context. A fourth is proposed, but only provisionally, in the conclusion of this work. The aspects resistant to uploading are defined and discussed as situatedness, plurality, and adaptability to ambiguity. Each of these aspects relates to one of the three steps of mind- uploading summarized in Nick Bostrom’s treatment of the subject. -

German and Dutch Courses

Course Descriptions for German Courses Spring 2017 See also our courses listed under Literature in Translation. ----------------------------- German 101 First Semester German, 4 credits 001 09:55 AM 10:45 AM MTWRF 002 11:00 AM 11:50 AM MTWRF 003 11:00 AM 11:50 AM MTWRF 004 12:05 PM 12:55 PM MTWRF 005 01:20 PM 02:10 PM MTWRF 006 03:30 PM 04:50 PM MWR Prerequisites: None. (This course is also offered for graduate students as German 401.) Presumes no knowledge of the German language. In the course students learn basic vocabulary around topics such as classroom objects, daily routines, descriptions of people and objects, simple narration in present time, etc. German 101 covers material presented in the textbook VORSPRUNG from Kapitel 1 to Kapitel 6. Students read and discuss “real” texts (written by and for native) speakers from the start. Grammar is explained using examples from these texts as well as from a graphic novel, told in installments, that traces the journey of an American exchange student, Anna Adler, to the university in Tübingen as well as her adventures once there. The course also offers basic cultural insights and comparisons that are further elaborated on in second-year courses. Testing is done in increments of chapter quizzes; there is no mid- term and no traditional final exam. Students also complete writing & reading assignments as well as matching assessments, all with a take-home component. There are two oral projects. Class participation is encouraged and an attendance policy is in place. This course cannot be audited. -

Und Dooh Ist Vielleioht Niemand Inniger Damit Verbunden Als Ich

Durham E-Theses Sie haben mich immer in der Zuruckgesogenheit meiner Lebensart fur isoliert von der welt gehalten; und dooh ist vielleioht niemand inniger damit verbunden als ich Von Kleist, Heinrich How to cite: Von Kleist, Heinrich (1958) Sie haben mich immer in der Zuruckgesogenheit meiner Lebensart fur isoliert von der welt gehalten; und dooh ist vielleioht niemand inniger damit verbunden als ich, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9727/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 "Sie haben mich immer in der ZurLiokgesogenheit meiner Lebensart tUr isoliert von der Welt sehaltan; und dooh ist vielleioht niemand inniger dami t verbunden ala ioh." HEINRICH VON KLEIST. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Mitteilungen Für Die Presse

Read the speech online: www.bundespraesident.de Page 1 of 4 Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier in a video message for the digital ceremony “Thinker, Poet, Democrat. Heinrich Mann on his 150th Birthday” in Berlin on 25 March 2021 Good evening from Schloss Bellevue, wherever you are tuning in from. This is not the first time that Berlin’s Academy of the Arts is hosting a ceremony in Heinrich Mann’s honour. In March 1931, invitations were issued for an event on the premises of the Prussian Academy of Arts to congratulate the newly elected Chairman of its Literature Section on his 60th birthday. The guests at the time included Ricarda Huch and Alfred Döblin, and the speakers were Max Liebermann, Adolf Grimme and Thomas Mann. They hailed the great man as a modern artist and “clandestine politician”, as a “grand écrivain” and “European moralist”. That was how the writer Heinrich Mann was feted at the time, in the Weimar Republic. What a wonderful, illustrious gathering to mark his birthday. Today, the Academy of the Arts has issued another invitation to honour Heinrich Mann, this time on his 150th birthday. The setting is, for various reasons, slightly different than it was back then, with a livestream as opposed to a gala reception, a video message as opposed to a speech, and the Federal President in attendance as opposed to the great man’s brother and Nobel Laureate. Nevertheless, I am delighted that we want to try this evening to revive the spirit of Heinrich Mann and his age. We want to take a closer look at a writer, who after his death in 1950 was co opted by the GDR for its own political ends, who was eclipsed in West Germany by his renowned younger brother, and who is not forgotten yet whose works are seldom read today. -

An Introduction to the Songs of Felix Wolfes (1892-1971) with Complete Chronological Catalogue

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1995 An Introduction to the Songs of Felix Wolfes (1892-1971) With Complete Chronological Catalogue. Viola R. Dacus Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Dacus, Viola R., "An Introduction to the Songs of Felix Wolfes (1892-1971) With Complete Chronological Catalogue." (1995). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6004. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6004 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Univerzita J

Univerzita J. Selyeho – Pedagogická fakulta – Katedra modernej filológie Selye János Egyetem – Tanárképző Kar – Modern Filológiai Tanszék Predmet-Tantárgy: Literaturgeschichte 1880-1945 Vyučujúci – Oktató: doc. Károly Vajda, PhD. Tematický plán – Tematikus terv Školský rok – Iskolai év: 2014/2015 Kód – Kód: LT4 Ročník – Évfolyam: III Spôsob hodnotenia – Az értékelés módja: mündliche Prüfung Prednáška - Előadás / Seminár – Szeminárium Ziel des Kurses Das Anliegen der Vorlesungen und der anschließenden Seminare besteht in der Einführung der Studierenden in die wichtigsten literatur- und teilweise kulturgeschichtlichen Erscheinungen der Epoche 1880-1945. Großes Gewicht wird dabei auf innovative Initiativen gelegt. Aus dem Wirrwarr von Strömungen und Ismen werden eminente Erzählungen, Romane und Gedichte ausgewählt, besprochen und in ihren verschiedenen Zusammenhängen analysiert. 13 hétre lebontva /Semesterstruktur der Veranstaltungen: Wöchentlich findet je eine Doppelstunde statt, die in der Form entweder einer Seminarsitzung oder einer Vorlesung abgehalten wird (siehe einschlägige Anmerkung). 1 Epochale Fragen - Epochenmachende Zweifel (Vorl.) 2 Naturalismus - Hintergründe - Textproben (Sem.) 3 Naturalistisches Erzählen - Gerhart Hauptmann: Bahnwärter Thiel (Vorl.) 4 Jahrhundertwende - Donaumonarchie (Robert Musil: Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törleß, Sem.) 5 Erneuerung deutscher Erzählliteratur aus Prag (Rilke: Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge, Vorl.) 6 Neue Wege der Lyrik - Rilkes Dinggedichte (Sem.) 7 Expressionalismus und Kafka (Vorl.) 8 Literatur als Kult, Sprachkrise (Stefan George, Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Ein Brief, Sem.) 9 Romanliteratur um die Jahrhundertwende (Ricarda Huch, Thomas Mann, Vorl.) 10 Neuromantik, Hermann Hesse: Der Steppenwolf (Sem.) 11 Die Erneuerung des Theaters (Bertold Brecht, Vorl.) 12 Höllenfahrt Europa - Literatur im Schatten der Hitlerei (Sem.) 13 Epochenroman und Epochenlüge - Thomas Mann: Doktor Faustus (Vorl.) Fachliteratur Geschichte der Deutschen Literatur / Helmuth Nürnberger. - 1. -

Deutschland Im Spiegel Der Dichtung

DEUTSCHLAND © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by libraries associated to dandelon.com network. IM SPIEGEL DER DICHTUNG Zusammengestellt von Marianne Bernhard Inhalt VORWORT 5 Joseph von Eichendorff, Heimweh 7 • Heinrich Heine 7 AN DER NORDSEE 9 Christian Morgenstern, In den Dünen 9 • Theodor Storm, Ostern 9 • Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, Auf dem Deich 10 FLENSBURG 11 Konrad Weiss 11 HUSUM 12 Theodor Storm, Die Stadt 12 NORDERNEY 12 Heinrich Heine 12 AUF SYLT 13 Wilhelm Raabe 13 IM DITHMARSCHER LAND 14 Konrad Weiss 14 SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN 14 Karl Friedrich Straß, Matthäus Friedrich Chemnitz, Schleswig- Holstein, meerumschlungen 14 IN DER HEIDE 15 Theodor Storm, Abseits 15 • Theodor Storm, Über die Heide 16 • Ricarda Huch, Blühende Heide 16 AN DER NORDSEE 16 Heinrich Heine 16 • Christian Morgenstern, Nebel am Watten- mer 17 • Theodor Storm, Meeresstrand 17 • Wilhelm Busch, Einer Hotelbeschließerin ins Stammbuch 18 • Rainer Maria Rilke, Die Nordsee-Insel 19 HELGOLAND 21 Grün ist das Land 21 • Friedrich Hebbel 21 • Heinrich von Kleist 22 • Heinrich Heine, Meergruß 22 • Heinrich Heine 24 441 KIEL . 25 Pierre Bertius 25 • Johann Gottfried Seume 25 • Hermann Bier- natzki 25 • Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock 26 • Adelbert von Bau- dissin 26 HOLSTEIN 26 Johann Heinrich Voss 26 LÜBECK 26 Franz Hogenberg/Georg Braun 26 • Joseph von Eichendorff 27 • Emanuel Geibel 27 • Adelbert von Baudissin 28 • Theodor Storm, Der Bau der Marienkirche 28 • Thomas Mann 31 RATZEBURG 32 Ricarda Huch 32 ALTONA -

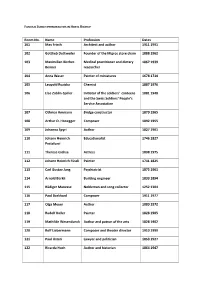

Room No. Name Profession Dates 101 Max Frisch Architect and Author 1911 1991

FAMOUS ZURICH PERSONALITIES IN HOTEL RIGIHOF Room No. Name Profession Dates 101 Max Frisch Architect and author 1911 1991 102 Gottlieb Duttweiler Founder of the Migros store chain 1888 1962 103 Maximilian Bircher- Medical practitioner and dietary 1867 1939 Benner researcher 104 Anna Waser Painter of miniatures 1678 1714 105 Leopold Ruzicka Chemist 1887 1976 106 Else Züblin-Spiller Initiator of the soldiers‘ canteens 1881 1948 and the Swiss Soldiers‘ People’s Service Association 107 Othmar Ammann Bridge constructor 1879 1965 108 Arthur O. Honegger Composer 1892 1955 109 Johanna Spyri Author 1827 1901 110 Johann Heinrich Educationalist 1746 1827 Pestalozzi 111 Therese Giehse Actress 1898 1975 112 Johann Heinrich Füssli Painter 1741 1825 113 Carl Gustav Jung Psychiatrist 1875 1961 114 Arnold Bürkli Building engineer 1833 1894 115 Rüdiger Manesse Nobleman and song collector 1252 1304 116 Paul Burkhard Composer 1911 1977 117 Olga Meyer Author 1889 1972 118 Rudolf Koller Painter 1828 1905 119 Mathilde Wesendonck Author and patron of the arts 1828 1902 120 Rolf Liebermann Composer and theatre director 1910 1999 121 Paul Usteri Lawyer and politician 1853 1927 122 Ricarda Huch Author and historian 1864 1947 200 Lukas Zeiner Glass painter 1454 1513 201 Anna Heer Gynaecologist and surgeon 1863 1918 202 Johann Caspar Lavater Pastor and author 1741 1801 203 Alfred F. Bluntschli Architect 1842 1930 204 Verena Loewensberg Painter 1912 1986 205 Conrad Ferdinand Author 1825 1898 Meyer 206 Suzanne Perrottet Dance educationalist and therapist 1889 1983 207 -

German Studies Grant Brochure

Thomas Saine (1941- Hans Wagener (1940- 2013) was an 2013) was a prolific scholar internationally noted who published scholar of eighteenth- monographs and articles century German culture on topics ranging from the (history, philosophy, German Baroque all the literature, aesthetics), way to 20th-century particularly of the works writers such as Erich Maria Remarque, Erich of Karl Philipp Moritz, Georg Forster, and Kästner, Stefan Andres, FranK WedeKind, Goethe. He was one of the founders of the Gabriele Wohmann, Sarah Kirsch, Siegfried now well-established Goethe Society of North Lenz, Carl ZucKmeyer, Franz Werfel, Lion America and the founding editor of Feuchtwanger, and Robert Neumann. Indeed, the Goethe Yearbook, an important venue for interpreting literature in its historical and Eighteenth-Century Studies, which he edited political contexts was Hans's passion. He from 1982-1999. He began his career at Yale, taught at UCLA for over 40 years, and on his his undergraduate and graduate alma mater, website, he stated that he was passionate where he taught as assistant and associate about "the function of literature as an professor of German from 1969-1975. After expression and part of ongoing historical and two terms as Visiting Professor at the political debates.” Hans was PAMLA University of Cincinnati, Tom moved to UC President from 1990-91, served for many Irvine. Author of numerous booKs and articles years on the executive committee, and GERMAN and recipient of distinguished grants and presented papers at numerous PAMLA many accolades, he was a strong advocate for conferences. His unwavering dedication to STUDIES German Studies in the United States and an scholarship and German Studies is evident in accomplished practitioner of that discipline. -

The Critical Reception of German Poetry and Fiction in Translation by Specific American News Media, 1945-1960

The critical reception of German poetry and fiction in translation by specific American news media, 1945-1960 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Fousel, Kenneth Dale, 1930- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 14:22:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318920 THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF GERMAN POETRY AND FICTION IN . -'TRANSLATION BY SPECIFIC AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA, 1945-1960 b y : . " ' • . • Kenneth D, Fousel — A Thesis Submitted, to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements' For the Degree of . ' MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College - THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1962 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree ait the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use. of the material is in the interest of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Lyrisches Gespür

Burkhard Lyrisches Gespür Vom geheimen Sensorium moderner Poesie Wilhelm Fink INHALTSVERZEICHNIS EINLEITUNG den des Gespürs (S. 17)-Woran erkennt man „lyrisches Gespür"? (S. - Das sprachliche Indiz (S. 24) - Das transitorische Indiz (S. 26) - Das atmosphärische Indiz (S. 29) - Das hypothetische Indiz (S. 31) - Das rhythmische Indiz (S. 34) - Situationslyrik: Zum terminus einer neuphänomenologischen Poetik (S. 38) - Zur These: Leiblichkeit als Entdeckung moderner Lyrik (S. 43) DER BEGRIFF DES GESPÜRS 49 Das Spüren und das Gespür (S. 52) - Bauchgefühle: Gespür als intuitive Entscheidungshilfe (S. 54) Könnerschaft: Gespür als Erfahrungswissen (S. 57) — Vom Verdichtungsbereich zum Verankerungspunkt: Gespür als situatives Sensorium (S. 59) - Außengründe: Zur Kunst des Spurenlesens (S. 61) - Außengründe deuten: Zum Begriff der Abduktion (S. 64) - Innengründe: Das Spüren als „Einheitsarbeit" (S. 67) - Innengründe deuten: Zwischen Authentizität und Leiblichkeit (S. 69) - Zusammenfassung (S. 71) STIMMUNGEN - ATMOSPHÄREN - SITUATIONEN: LYRISCHES GESPÜR ALS GESTALTUNG DES AMORPHEN 73 Stimmungen als „background (S. 76) - Stimmungen als feelings" (S. 79) - Stimmungen als „räumlich ergossene Atmosphären" (S. 82) - Epoche oder Ingression? Stimmungsdynamiken im Vergleich (S. 84) - Epoche oder Ingression? Spürende Nachtgedichte im Vergleich (S. 88) - Zusammenfassung (S. 90) „SITUATIONSLYRIK": ZUM PROFIL EINER NEUPHÄNOMENOLOGISCHEN POETIK Ausgangspunkt „Stimmungslyrik": Zur Geschichte eines Missverständnisses (S. 93) - Rettungsversuche (I): Die Stimmungslyrik im Symbolismus (S. 97) - Rettungsversuche (II): Stimmungslyrik bei Staiger, Kommereil, Böckmann und (S. 102) - Die finale Kritik: Friedrich, Link, Lamping, Conrady (S. 104) - Der Lösungsvorschlag: Stimmungslyrik als Situationslyrik (S. 107) - A) Das lyrische Ich präpersonale Form der Subjektivität (S. 109) - B) Die Abduktion als Fiktionalisierung leiblicher Erfahrung (S. C) Lyrische Bilderzwischen Verdichtung und Verankerung (S. - D) Engung und Weitung als metrische Kategorien (S. -

Verzeichnis Der Gedichte Naturstimmungen Und Naturbilder Seite Ostern Joh

Verzeichnis der Gedichte Naturstimmungen und Naturbilder Seite Ostern Joh. Wol'fgang Goethe 7 Mondnacht Joseph v. Eichendorff 8 Er ists . Eduard Mörike 8 Traumwald Christian Morgenstern 8 Abseits Theodor Storm 9 Feldeinsamkeit Hermann Alkners. .. 9 Aus "Phantasus" Arno Holz io Seltsame Mondnacht Hans Siemsen io Schöne weite Welt Lied des Türmers Joh. Wolfgang Goethe ... 12 Sehnsucht Joseph v. Eichendorff ... 12 Die Sterne Ernst Moritz Arndt... .. i3 Das Hirtenfeuer Annette v. Droste-Hüls- hoff 14 Abendlied Gottfried Keller- 15 Wandern Der junge Schiffer Friedrich Hebbel 16 Wanderlied Emanuel Geibel 19 Wanderlied der Jugend ... .. Hermann Claudius 20 Wanderlied Jürgen'Brand 20 Naturgewalten Die Fe'uersbrunst Friedrich Schiller .. 21 Die Brücke am Tay Theodor Fontane 23 Trutz blanke Hans Detlev v. Liliencron .. 24 Liebe Schön Rohtraut . Eduard Mörike Es waren zwei Königskinder . Volkslied 27 Heideröslein . Joh. Wolfgang Goethe . 28 Es fiel ein Reif . Volkslied .. 28 Das zerbrochene Ringlein . Joseph v. Eichendorff . 28 http://d-nb.info/992235847 t Mutterliebe und Väterrat Seite So einer war auch er Arno Holz 29 Wiegenlied .... Matthias Claudius 30 Mutterns Hände . : . •• Kurt Tucholsky •. 32' Neueste Väterweisheit Theodor Fontane . .. .. 33 Für meine Söhne Theodor Storni 33 Das Erkennen Johann Nepomuk Vogl . 34 Helden John Maynard Theodor Fontane 35 Der Lotse Ludwig Giesebrecht . 36 Nis Randers Otto Ernst 38 Pidder Lüng .... Detlev v. Liliencron . 3g Jacta est alea Conrad Ferdinand Meyer 41 Durch die Jahrhunderte Belsazer Heinrich Heine 43 Die Bürgschaft Friedrich Schiller 45 Die Weiber von Weinsberg' ... Adalbert v. Chamisso . 48 Archibald Douglas Theodor Fontane 49 Ein Lied der Bauern Heinrich von Reder . 51 Die Füsse im Feuer Conrad Ferdinand Meyer 53 Wiegenlied Ricarda Huch 54 Die Balinesenfrauen auf Lombok Theodor Fontane 56 Wie ist doch die Zeitung so in teressant Hoffmann v.