Post-Socialist Urban Infrastructures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WSN in Prague Metro

WSN in Prague metro Martin Vaníček - CTU WSN installation in Prague - past • Test site Near Dejvická metro station (~70m) • The reason for this site was to test the WSN network in the environment of Prague metro, especially as on line A is installed a signalling system running on the Wi-Fi band as Zig-bee • 8 wireless nodes + Stargate gateway installed • 5 nodes + Stargate in one ring • 3 nodes along tunnel ~ 17m distance • Linksys GPRS router for internet access next to Stargate • Encountered problems • GPRS connection dropping, most probably due to the distance from the station • Stargate stopped working due to faulty power supply, the WSN removed during January visit WSN in Prague Metro Prague 4 - 5 November 2008 Martin Vaníček WSN installation in Prague - present • Situation at line C between Nádraží Holešovice and Vltavská stations: • WSN is installed in similar set up as in London • The gateway used is Balloon computer & MIB600 board • Internet – using USB modem connected to Balloon • The signal is strong enough as we are closer to the station • The systém is working fine since August this year • Peter Bennet will give you more details in his presentation WSN in Prague Metro Prague 4 - 5 November 2008 Martin Vaníček WSN installation in Prague – future • Proposal: • WSN will be installed in 2 more locations in Prague metro – near station Můstek on line A and on Nuselský bridge on line C • WSN will be based on Crossbow‘s implementation (Stargate Netbridge gateway with X-mesh protocol) the collection of data from network will be based on Cambridge implementation as is on Balloon • Internet connection will be done using Linksys router • Netbridge gateway will be connected with MIB600 board via about 100m long Ethernet cable that is proved to work in metro on line C, we will try to implement powering of MIB 600 by PoE • Regarding sensors we want to install 4 inclinometers and 2 crackmeters on each site of course together with measurements of temperature, pressure and humidity. -

Final Exploitation Plan

D9.10 – Final Exploitation Plan Jorge Lpez (Atos), Alessandra Tedeschi (DBL), Julian Williams (UDUR), abio Massacci (UNITN), Raminder Ruprai (NGRID), Andreas Schmitz ( raunhofer), Emilio Lpez (URJC), Michael Pellot (TMB), Zden,a Mansfeldov. (ISASCR), Jan J/r0ens ( raunhofer) Pending of approval from the Research Executive Agency - EC Document Number D1.10 Document Title inal e5ploitation plan Version 1.0 Status inal Work Packa e WP 1 Deliverable Type Report Contractual Date of Delivery 31 .01 .20 18 Actual Date of Delivery 31.01.2018 Responsible Unit ATOS Contributors ISASCR, UNIDUR, UNITN, NGRID, DBL, URJC, raunhofer, TMB (eyword List E5ploitation, ramewor,, Preliminary, Requirements, Policy papers, Models, Methodologies, Templates, Tools, Individual plans, IPR Dissemination level PU SECONO.ICS Consortium SECONOMICS ?Socio-Economics meets SecurityA (Contract No. 28C223) is a Collaborative pro0ect) within the 7th ramewor, Programme, theme SEC-2011.E.8-1 SEC-2011.7.C-2 ICT. The consortium members are: UniversitG Degli Studi di Trento (UNITN) Pro0ect Manager: prof. abio Massacci 1 38100 Trento, Italy abio.MassacciHunitn.it www.unitn.it DEEP BLUE Srl (DBL) Contact: Alessandra Tedeschi 2 00113 Roma, Italy Alessandra.tedeschiHdblue.it www.dblue.it raunhofer -Gesellschaft zur Irderung der angewandten Contact: Prof. Jan J/r0ens 3 orschung e.V., Hansastr. 27c, 0an.0uer0ensHisst.fraunhofer.de 80E8E Munich, Germany http://www.fraunhofer.de/ UNIVERSIDAD REL JUAN CARLOS, Contact: Prof. David Rios Insua 8 Calle TulipanS/N, 28133, Mostoles david.riosHur0c.es -

Ita Tribune 31

N° 31 - MAY 2007 - ISSN 1267-8422 TRIBUNE I TA newsletter la lettre de l'AITES Visualisation of the Lochkov tunnel portal Visualisation des têtes du tunnel de Lochkov. SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS BUREAU EXÉCUTIF ET COMITÉ DE RÉDACTION EXECUTIVE COUNCIL AND EDITORIAL BOARD H . P a r k e r U S A Editorial 6 Editorial A . M . Muir Wood U K A . A s s i s B r a z i l Focus sur la Rep. Tchèque 7 Focus on Czech Republic K . O n o J a p a n M . K n i g h t s U K H . Wa g n e r A u s t r i a Résumés des présentations de 20 WTC’07 Open Session Y. E r d e m Tu r k e y la séance publique WTC’07 Abstracts M . B e l e n k i y R u s s i a E . G r ø v N o r w a y Rapports 2006 des Nations 22 Member Nations 2006 F. Grübl G e r m a n y Membres reports Y. L e b l a i s F r a n c e P. Grasso I t a l y Rapports 2006 des "Prime 40 ITA "Prime Sponsors” 2006 W. Liu P R C h i n a Sponsors" de l’AITES reports I H r d i n a Czech Rep. F. Vu i l l e u m i e r S w i t z e r l a n d Rapports 2006 des 45 ITA "Supporters” 2006 reports C . -

Prague Metro Project Line a Extension

PRAGUE METRO PROJECT LINE A EXTENSION PRAKAB.CZ | MEMBER OF SKB-GROUP KEY FACTS • 4 metro stations – Červený Vrch, Veleslavín, Petřiny and Motol, beyond the Dejvická station • Total construction length 6134 m • Completed and opened for public April 6, 2015 PROJECT Construction duration 5 years • The aim of the extension of metro line A was to Investment approx. 20 billion CZK • significantly improve transportation services to the muni- More than 600 km of cables PRAKAB • cipal district Prague 6, and reducing bus transportation. After its opening pollution from buses was greatly reduced. The metro line extension to Motol Hospital helped to improve the health care avai- lability in the Prague 6 district and its surroundings. Motol Hospital is at the same time a big employer, thus the extension of metro line A ensured a better way to work for thousands of employees. CONTRACT The construction project of the four new stations of the metro line A was partially financed from EU funds. Out of the total of 20 billion CZK more than 100 million was invested in the cables from PRAKAB PRAŽSKÁ KABELOVNA, s.r.o.. Electrical energy 230/400V at the new stations of line A is distribut- ed either directly to respective place of consumption, or to sub distribu- tion switchboards located in the separate switch rooms. The important devices are connected directly to the main switchboard in the electrical station. The total length of low-voltage cables of the Prague metro is over several thousand km and for this reason special cable trays, rooms and ducts are built, with 22kV cables conducted simultaneously. -

Podzemne Željeznice U Prometnim Sustavima Gradova

Podzemne željeznice u prometnim sustavima gradova Lesi, Dalibor Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Fakultet prometnih znanosti Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:119:523020 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-06 Repository / Repozitorij: Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences - Institutional Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FAKULTET PROMETNIH ZNANOSTI DALIBOR LESI PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA DIPLOMSKI RAD Zagreb, 2017. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet prometnih znanosti DIPLOMSKI RAD PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA SUBWAYS IN THE TRANSPORT SYSTEMS OF CITIES Mentor: doc.dr.sc.Mladen Nikšić Student: Dalibor Lesi JMBAG: 0135221919 Zagreb, 2017. Sažetak Gradovi Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne i Liverpool su europski gradovi sa različitim sustavom podzemne željeznice čiji razvoj odgovara ekonomskoj situaciji gradskih središta. Trenutno stanje pojedinih podzemno željeznićkih sustava i njihova primjenjena tehnologija uvelike odražava stanje razvoja javnog gradskog prijevoza i mreže javnog gradskog prometa. Svaki od prijevoznika u podzemnim željeznicama u tim gradovima ima različiti tehnički pristup obavljanja javnog gradskog prijevoza te korištenjem optimalnim brojem motornih prijevoznih jedinica osigurava zadovoljenje potreba javnog gradskog i metropolitanskog područja grada. Kroz usporedbu tehničkih podataka pojedinih podzemnih željeznica može se uvidjeti i zaključiti koji od sustava podzemnih željeznica je veći i koje oblike tehničkih rješenja koristi. Ključne riječi: Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne, Liverpool, podzemna željeznica, javni gradski prijevoz, linija, tip vlaka, tvrtka, prihod, cijena. Summary Cities Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne and Liverpool are european cities with different metro system by wich development reflects economic situation of city areas. -

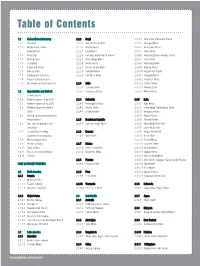

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

Innovative, Inspiring: Lrt's Great 12 Months

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tramnews.net JANUARY 2014 NO. 913 INNOVATIVE, INSPIRING: LRT’S GREAT 12 MONTHS Cincinnati: Streetcar scheme to hit the buffers? Adelaide plans all-new LRT network Alstom considers asset disposals Midland Metro growth linked to HS2 ISSN 1460-8324 £4.10 Chicago Kyiv 01 Modernisation and Football legacy and renewals on the ‘L’ reconnection plans 9 771460 832036 FOR bOOKiNgs AND sPONsORsHiP OPPORTUNiTiEs CALL +44 (0) 1733 367603 11-12 June 2014 – Nottingham, UK 2014 Nottingham Conference Centre The 9th Annual UK Light Rail Conference and exhibition brings together 200 decision-makers for two days of open debate covering all aspects of light rail development. Delegates can explore the latest industry innovation and examine LRT’s role in alleviating congestion in our towns and cities and its potential for driving economic growth. Packed full of additional delegate benefits for 2014, this event also includes a system visit in conjunction with our hosts Nottingham Express Transit and a networking dinner open to all attendees hosted by international transport operator Keolis. Modules and debates for 2013 include: ❱ LRT’s strategic role as a city-building tool ❱ Manchester Metrolink expansion: The ‘Network Effect’ ❱ Tramways as creators of green corridors ❱ The role of social media and new technology ❱ The value of small-start/heritage systems ❱ Ticketing and fare collection innovation ❱ Funding light rail in a climate of austerity ❱ Track and trackform: Challenges and solutions ❱ HS2: A golden -

Orgnisations That Participated in the Uitp Declaration on Climate Leadership at the 2014 Un Secretary General Climate Summit

INTRODUCTION UITP is the only worldwide network to bring together all public transport stakeholders and all sustainable transport modes, including vehicle manufacturers and technology providers. UITP has over 1,600 members in 100 countries and represents the key players needed for low carbon urban mobility. ABOUT THIS REPORT For the occasion of COP 25, this report provides an update on implementation of the actions pledged under the UITP Declaration on Climate Leadership since it was launched at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Summit in 2014. This is to provide a stock take of collective action in the public transport sector and to share stories of implementation which can provide an inspiration for action to help inform the update of Parties’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 6 KEY MESSAGES FOR COP 25 Key Message 1: Net decarbonisation of the transport sector by 2050 is possible, but will require an immediate and concerted turnaround of global policy action. Key Message 2: Sustainable urban mobility based on public transport is necessary for countries to deliver on their NDCs. Key Message 3: Safe, low carbon, efficient and affordable mobility, notably by expanding public, walking and cycling for all is essential to sustainable human development and must be enabled in all climate and sustainable development policies. Key Message 4: Investments in low and zero carbon public transport yields substantial, long-term benefits by increasing social cohesion and equity and reducing disability and deaths. Key Message 5: Integrated mobility solutions on the backbone of public transport has the potential to transform cities into more efficient, low carbon, clean air, people-centred and planet-sensitive solutions. -

ISTT Recognises Mears Group for Complicated Installation – PAGE 16

ISSUE 38 | WINTER 2018 The official publication of the International Society for Trenchless Technology AWARD-WINNING ISTT recognises Mears Group HDD for complicated installation – PAGE 16 No-Dig flourishes in NASTT No-Dig Findings of CIPP 14 the Americas 26 Show preview 47 report challenge ISO 9001:2008 FM 56735 FM 588513 17-12-11-012_ID18023_eAZ_HDD_Trenchless International_210x297_RZgp Flexibility Trailer, crawler or modular rigs by Herrenknecht. Quick installation, successful worldwide. FP AD 1 Power PAGE ONEE f fi c i e n t Herrenknecht HDD rigs with 100–600 t. Torque and pull forces continuously adjustable for optimum performance at each operating point. Plus tailor-made onsite services and a full range Herrenknechtof additional equipment. Control Modern sensor systems with real-time monitoring and online analysis of drilling data. To protect drill rods and tools in the borehole. For maximum performance. Pioneering Underground Technologies www.herrenknecht.com 17-12-11-012_ID18023_eAZ_HDD_Trenchless International_210x297_RZgp.indd 1 11.12.17 13:04 | CONTENTS | INSIDE TRENCHLESS INTERNATIONAL 16 | Cover Story PROJECT AWARD Mears Group has received as ISTT Award at Trenchless World Congress for a challenging HDD installation in Florida, US. 14 26 FP AD 2 GREAT SOUTHERN PRESS PTY LTD Primus Line ACN 005 716 825 ABN 28 096 872 004 Suite 1, Level 3 169-171 Victoria Parade Fitzroy VIC 3065 Australia TEL: +61 3 9248 5100 REPORTS NASTT NO-DIG SHOW [email protected] From the Chairman’s desk 6 Event preview 26 www.trenchlessinternational.com -

Free-Map.Pdf

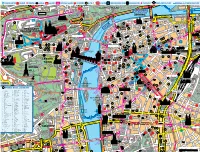

122 TOURIST CENTRE MUSEUM THEATRE CHURCH GALLERY NG NATIONAL GALLERY MONUMENT HOTEL HOSPITAL PEDESTRIANIZED ZONE UNDERGROUND TRAM STOP WALKS MEETING POINT BOAT DEPARTURE POINT 8 15 Štefánikův Bridge LUNCH/DINNER BOAT eše CRUISE DEPARTURE 14 Tram stop 22 for easy access to Prague Castle Classic River Boat nábř. Edvarda Ben 6 Pražský 22 23 hrad 23 Čechův 15 Bridge Postal 45 Museum 43 56 23 89 St. Agnes 12 sq. Convent Golden Lane 53 Old Castle Stairs JAZZ BOAT JEWISH 20 5 s DEPARTURE HRADČANY The Office TOWN St. Peter r St. George’ sq. Church PRAGUE CASTLE Basilica sq. 26 79 123 of the Government Synagogu Old-New Spanish St. Castullus St. Vitus Synagogue Church Cathedral All 72 Saints 6 Prague Valdštejnské 58 24 City Prague Castle 2- e square Kotva 69 52 Museum Complex Mánesův VltavaBridge Rive 26 99 14 square 114 Shopping 18 Castle Stairs 117 16 Mall 75 Bus Station square sq. 15 50 Florenc Maiselova St. James Palladium 107 113 15 11 the Greater 25 Shopping Mall 80 101 23 Church 64 EXC 111 Meeting 76 Žatecká 44 42 110 Point 83 103 19 HANGE St. Nicholas Church 29 7 Franz Republic 71 St. Nicholas sq. Franz Kafka Kafka sq. 48 Museum 39 sq. Church Old Týn Station Town PowderMunicipal Mariánské SquareChurch Gate House 78 sq. 15 Astronomical 21 60 Lennon 97 MaléClock 40 23 109 Wall OLD sq. 115 TOWN 112 30 sq. -15 sq. sq. 121 sq. 1 14 Havelský 62 108 Market 2 73 Na Příkopě 12 102 Strahov Jubilee 70 54 St. -

A Questionnaire Study About Fire Safety in Underground Rail Transportation Systems

A questionnaire study about fire safety in underground rail transportation systems Karl Fridolf, Daniel Nilsson Department of Fire Safety Engineering and Systems Safety Lund University, Sweden Brandteknik och Riskhantering Lunds tekniska högskola Lunds universitet Lund 2012 A questionnaire study about fire safety in underground rail transportation systems Karl Fridolf, Daniel Nilsson Lund 2012 A questionnaire study about fire safety in underground rail transportation systems Karl Fridolf, Daniel Nilsson Report 3164 ISSN: 1402-3504 ISRN: LUTVDG/TVBB--3164--SE Number of pages: 25 Illustrations: Karl Fridolf Keywords questionnaire study, fire safety, evacuation, human behaviour in fire, underground rail transportation system, metro, tunnel. © Copyright: Department of Fire Safety Engineering and Systems Safety, Lund University Lund 2012. Brandteknik och Riskhantering Department of Fire Safety Engineering Lunds tekniska högskola and Systems Safety Lunds universitet Lund University Box 118 P.O. Box 118 221 00 Lund SE-221 00 Lund Sweden [email protected] http://www.brand.lth.se [email protected] http://www.brand.lth.se/english Telefon: 046 - 222 73 60 Telefax: 046 - 222 46 12 Telephone: +46 46 222 73 60 Fax: +46 46 222 46 12 Summary A questionnaire study was carried out with the main purpose to collect information related to the fire protection of underground rail transportation systems in different countries. Thirty representatives were invited to participate in the study. However, only seven responded and finally completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was available on the Internet and included a total of 16 questions, which were both close-ended and open-ended. Among other things, the questions were related to typical underground stations, safety instructions and exercises, and technical systems, installations and equipment. -

Developing Strategic Approaches to Infrastructure Planning Developing Strategic Approaches to Infrastructure Planning

CPB Corporate Partnership Board Developing Strategic Approaches to Infrastructure Planning Developing Strategic Approaches to Infrastructure Planning Research Report 2021 The International Transport Forum The International Transport Forum is an intergovernmental organisation with 62 member countries. It acts as a think tank for transport policy and organises the Annual Summit of transport ministers. ITF is the only global body that covers all transport modes. The ITF is politically autonomous and administratively integrated with the OECD. The ITF works for transport policies that improve peoples’ lives. Our mission is to foster a deeper understanding of the role of transport in economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusion and to raise the public profile of transport policy. The ITF organises global dialogue for better transport. We act as a platform for discussion and pre- negotiation of policy issues across all transport modes. We analyse trends, share knowledge and promote exchange among transport decision-makers and civil society. The ITF’s Annual Summit is the world’s largest gathering of transport ministers and the leading global platform for dialogue on transport policy. The Members of the Forum are: Albania, Armenia, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China (People’s Republic of), Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Republic of Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States and Uzbekistan.