Math 1330 - Section 4.1 Special Triangles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Square Rectangle Triangle Diamond (Rhombus) Oval Cylinder Octagon Pentagon Cone Cube Hexagon Pyramid Sphere Star Circle

SQUARE RECTANGLE TRIANGLE DIAMOND (RHOMBUS) OVAL CYLINDER OCTAGON PENTAGON CONE CUBE HEXAGON PYRAMID SPHERE STAR CIRCLE Powered by: www.mymathtables.com Page 1 what is Rectangle? • A rectangle is a four-sided flat shape where every angle is a right angle (90°). means "right angle" and show equal sides. what is Triangle? • A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. what is Octagon? • An octagon (eight angles) is an eight-sided polygon or eight-gon. what is Hexagon? • a hexagon is a six-sided polygon or six-gon. The total of the internal angles of any hexagon is 720°. what is Pentagon? • a plane figure with five straight sides and five angles. what is Square? • a plane figure with four equal straight sides and four right angles. • every angle is a right angle (90°) means "right ang le" show equal sides. what is Rhombus? • is a flat shape with four equal straight sides. A rhombus looks like a diamond. All sides have equal length. Opposite sides are parallel, and opposite angles are equal what is Oval? • Many distinct curves are commonly called ovals or are said to have an "oval shape". • Generally, to be called an oval, a plane curve should resemble the outline of an egg or an ellipse. Powered by: www.mymathtables.com Page 2 What is Cube? • Six equal square faces.tweleve edges and eight vertices • the angle between two adjacent faces is ninety. what is Sphere? • no faces,sides,vertices • All points are located at the same distance from the center. what is Cylinder? • two circular faces that are congruent and parallel • faces connected by a curved surface. -

Applying the Polygon Angle

POLYGONS 8.1.1 – 8.1.5 After studying triangles and quadrilaterals, students now extend their study to all polygons. A polygon is a closed, two-dimensional figure made of three or more non- intersecting straight line segments connected end-to-end. Using the fact that the sum of the measures of the angles in a triangle is 180°, students learn a method to determine the sum of the measures of the interior angles of any polygon. Next they explore the sum of the measures of the exterior angles of a polygon. Finally they use the information about the angles of polygons along with their Triangle Toolkits to find the areas of regular polygons. See the Math Notes boxes in Lessons 8.1.1, 8.1.5, and 8.3.1. Example 1 4x + 7 3x + 1 x + 1 The figure at right is a hexagon. What is the sum of the measures of the interior angles of a hexagon? Explain how you know. Then write an equation and solve for x. 2x 3x – 5 5x – 4 One way to find the sum of the interior angles of the 9 hexagon is to divide the figure into triangles. There are 11 several different ways to do this, but keep in mind that we 8 are trying to add the interior angles at the vertices. One 6 12 way to divide the hexagon into triangles is to draw in all of 10 the diagonals from a single vertex, as shown at right. 7 Doing this forms four triangles, each with angle measures 5 4 3 1 summing to 180°. -

Circle Theorems

Circle theorems A LEVEL LINKS Scheme of work: 2b. Circles – equation of a circle, geometric problems on a grid Key points • A chord is a straight line joining two points on the circumference of a circle. So AB is a chord. • A tangent is a straight line that touches the circumference of a circle at only one point. The angle between a tangent and the radius is 90°. • Two tangents on a circle that meet at a point outside the circle are equal in length. So AC = BC. • The angle in a semicircle is a right angle. So angle ABC = 90°. • When two angles are subtended by the same arc, the angle at the centre of a circle is twice the angle at the circumference. So angle AOB = 2 × angle ACB. • Angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal. This means that angles in the same segment are equal. So angle ACB = angle ADB and angle CAD = angle CBD. • A cyclic quadrilateral is a quadrilateral with all four vertices on the circumference of a circle. Opposite angles in a cyclic quadrilateral total 180°. So x + y = 180° and p + q = 180°. • The angle between a tangent and chord is equal to the angle in the alternate segment, this is known as the alternate segment theorem. So angle BAT = angle ACB. Examples Example 1 Work out the size of each angle marked with a letter. Give reasons for your answers. Angle a = 360° − 92° 1 The angles in a full turn total 360°. = 268° as the angles in a full turn total 360°. -

20. Geometry of the Circle (SC)

20. GEOMETRY OF THE CIRCLE PARTS OF THE CIRCLE Segments When we speak of a circle we may be referring to the plane figure itself or the boundary of the shape, called the circumference. In solving problems involving the circle, we must be familiar with several theorems. In order to understand these theorems, we review the names given to parts of a circle. Diameter and chord The region that is encompassed between an arc and a chord is called a segment. The region between the chord and the minor arc is called the minor segment. The region between the chord and the major arc is called the major segment. If the chord is a diameter, then both segments are equal and are called semi-circles. The straight line joining any two points on the circle is called a chord. Sectors A diameter is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. It is, therefore, the longest possible chord of a circle. In the diagram, O is the center of the circle, AB is a diameter and PQ is also a chord. Arcs The region that is enclosed by any two radii and an arc is called a sector. If the region is bounded by the two radii and a minor arc, then it is called the minor sector. www.faspassmaths.comIf the region is bounded by two radii and the major arc, it is called the major sector. An arc of a circle is the part of the circumference of the circle that is cut off by a chord. -

Petrie Schemes

Canad. J. Math. Vol. 57 (4), 2005 pp. 844–870 Petrie Schemes Gordon Williams Abstract. Petrie polygons, especially as they arise in the study of regular polytopes and Coxeter groups, have been studied by geometers and group theorists since the early part of the twentieth century. An open question is the determination of which polyhedra possess Petrie polygons that are simple closed curves. The current work explores combinatorial structures in abstract polytopes, called Petrie schemes, that generalize the notion of a Petrie polygon. It is established that all of the regular convex polytopes and honeycombs in Euclidean spaces, as well as all of the Grunbaum–Dress¨ polyhedra, pos- sess Petrie schemes that are not self-intersecting and thus have Petrie polygons that are simple closed curves. Partial results are obtained for several other classes of less symmetric polytopes. 1 Introduction Historically, polyhedra have been conceived of either as closed surfaces (usually topo- logical spheres) made up of planar polygons joined edge to edge or as solids enclosed by such a surface. In recent times, mathematicians have considered polyhedra to be convex polytopes, simplicial spheres, or combinatorial structures such as abstract polytopes or incidence complexes. A Petrie polygon of a polyhedron is a sequence of edges of the polyhedron where any two consecutive elements of the sequence have a vertex and face in common, but no three consecutive edges share a commonface. For the regular polyhedra, the Petrie polygons form the equatorial skew polygons. Petrie polygons may be defined analogously for polytopes as well. Petrie polygons have been very useful in the study of polyhedra and polytopes, especially regular polytopes. -

Foundations of Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Foundations of geometry Lawrence Michael Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Lawrence Michael, "Foundations of geometry" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3419 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Approved by: 3)?/08 Murran, Committee Chair Date _ ommi^yee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member 1 Peter Williams, Chair, Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics iii Abstract In this paper, a brief introduction to the history, and development, of Euclidean Geometry will be followed by a biographical background of David Hilbert, highlighting significant events in his educational and professional life. In an attempt to add rigor to the presentation of Geometry, Hilbert defined concepts and presented five groups of axioms that were mutually independent yet compatible, including introducing axioms of congruence in order to present displacement. -

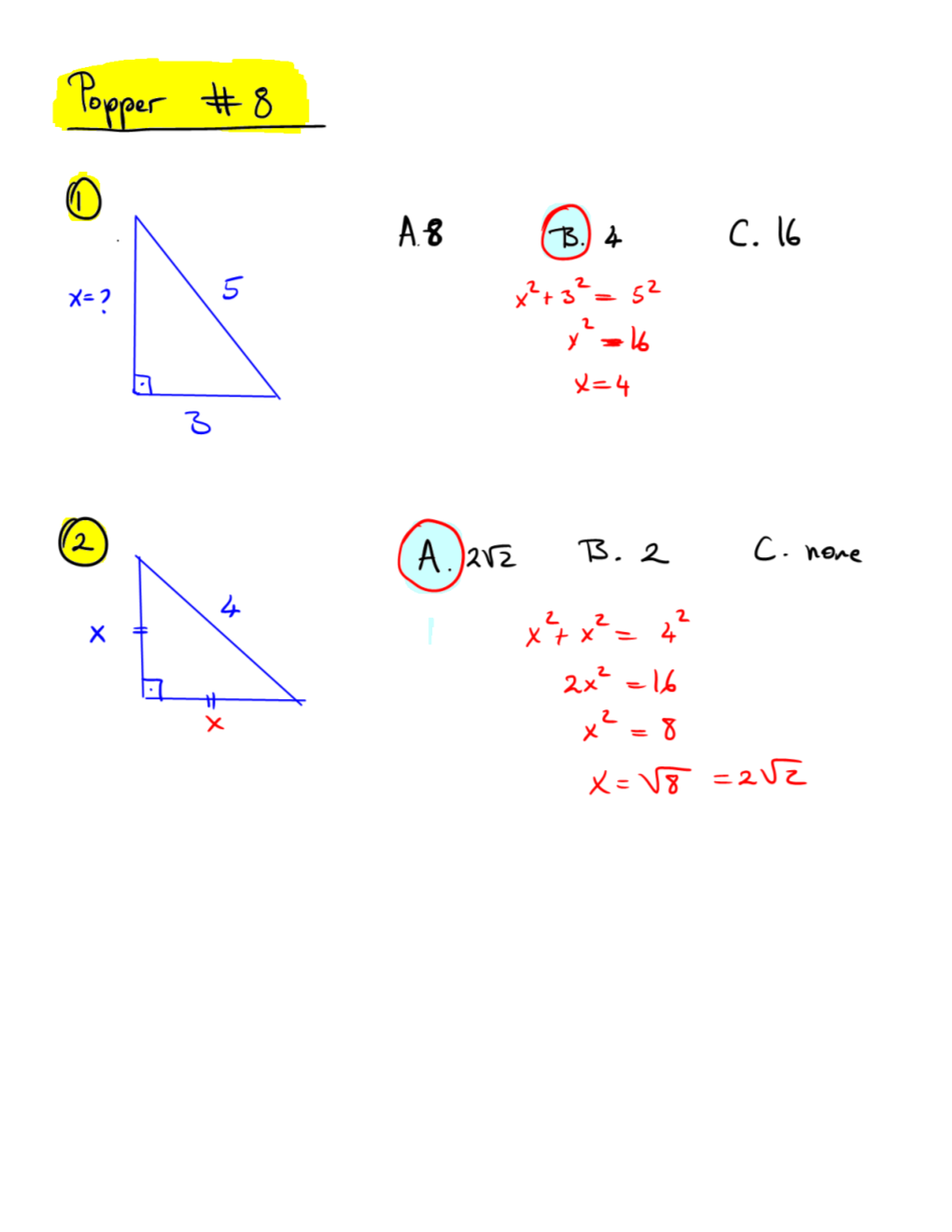

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

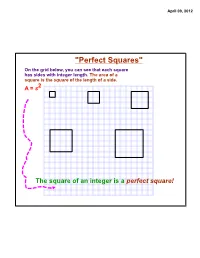

"Perfect Squares" on the Grid Below, You Can See That Each Square Has Sides with Integer Length

April 09, 2012 "Perfect Squares" On the grid below, you can see that each square has sides with integer length. The area of a square is the square of the length of a side. A = s2 The square of an integer is a perfect square! April 09, 2012 Square Roots and Irrational Numbers The inverse of squaring a number is finding a square root. The square-root radical, , indicates the nonnegative square root of a number. The number underneath the square root (radical) sign is called the radicand. Ex: 16 = 121 = 49 = 144 = The square of an integer results in a perfect square. Since squaring a number is multiplying it by itself, there are two integer values that will result in the same perfect square: the positive integer and its opposite. 2 Ex: If x = (perfect square), solutions would be x and (-x)!! Ex: a2 = 25 5 and -5 would make this equation true! April 09, 2012 If an integer is NOT a perfect square, its square root is irrational!!! Remember that an irrational number has a decimal form that is non- terminating, non-repeating, and thus cannot be written as a fraction. For an integer that is not a perfect square, you can estimate its square root on a number line. Ex: 8 Since 22 = 4, and 32 = 9, 8 would fall between integers 2 and 3 on a number line. -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 April 09, 2012 Approximate where √40 falls on the number line: Approximate where √192 falls on the number line: April 09, 2012 Topic Extension: Simplest Radical Form Simplify the radicand so that it has no more perfect-square factors. -

Cyclic Quadrilaterals — the Big Picture Yufei Zhao [email protected]

Winter Camp 2009 Cyclic Quadrilaterals Yufei Zhao Cyclic Quadrilaterals | The Big Picture Yufei Zhao [email protected] An important skill of an olympiad geometer is being able to recognize known configurations. Indeed, many geometry problems are built on a few common themes. In this lecture, we will explore one such configuration. 1 What Do These Problems Have in Common? 1. (IMO 1985) A circle with center O passes through the vertices A and C of triangle ABC and intersects segments AB and BC again at distinct points K and N, respectively. The circumcircles of triangles ABC and KBN intersects at exactly two distinct points B and M. ◦ Prove that \OMB = 90 . B M N K O A C 2. (Russia 1995; Romanian TST 1996; Iran 1997) Consider a circle with diameter AB and center O, and let C and D be two points on this circle. The line CD meets the line AB at a point M satisfying MB < MA and MD < MC. Let K be the point of intersection (different from ◦ O) of the circumcircles of triangles AOC and DOB. Show that \MKO = 90 . C D K M A O B 3. (USA TST 2007) Triangle ABC is inscribed in circle !. The tangent lines to ! at B and C meet at T . Point S lies on ray BC such that AS ? AT . Points B1 and C1 lies on ray ST (with C1 in between B1 and S) such that B1T = BT = C1T . Prove that triangles ABC and AB1C1 are similar to each other. 1 Winter Camp 2009 Cyclic Quadrilaterals Yufei Zhao A B S C C1 B1 T Although these geometric configurations may seem very different at first sight, they are actually very related. -

Points, Lines, and Planes a Point Is a Position in Space. a Point Has No Length Or Width Or Thickness

Points, Lines, and Planes A Point is a position in space. A point has no length or width or thickness. A point in geometry is represented by a dot. To name a point, we usually use a (capital) letter. A A (straight) line has length but no width or thickness. A line is understood to extend indefinitely to both sides. It does not have a beginning or end. A B C D A line consists of infinitely many points. The four points A, B, C, D are all on the same line. Postulate: Two points determine a line. We name a line by using any two points on the line, so the above line can be named as any of the following: ! ! ! ! ! AB BC AC AD CD Any three or more points that are on the same line are called colinear points. In the above, points A; B; C; D are all colinear. A Ray is part of a line that has a beginning point, and extends indefinitely to one direction. A B C D A ray is named by using its beginning point with another point it contains. −! −! −−! −−! In the above, ray AB is the same ray as AC or AD. But ray BD is not the same −−! ray as AD. A (line) segment is a finite part of a line between two points, called its end points. A segment has a finite length. A B C D B C In the above, segment AD is not the same as segment BC Segment Addition Postulate: In a line segment, if points A; B; C are colinear and point B is between point A and point C, then AB + BC = AC You may look at the plus sign, +, as adding the length of the segments as numbers. -

Cyclic Quadrilaterals

GI_PAGES19-42 3/13/03 7:02 PM Page 1 Cyclic Quadrilaterals Definition: Cyclic quadrilateral—a quadrilateral inscribed in a circle (Figure 1). Construct and Investigate: 1. Construct a circle on the Voyage™ 200 with Cabri screen, and label its center O. Using the Polygon tool, construct quadrilateral ABCD where A, B, C, and D are on circle O. By the definition given Figure 1 above, ABCD is a cyclic quadrilateral (Figure 1). Cyclic quadrilaterals have many interesting and surprising properties. Use the Voyage 200 with Cabri tools to investigate the properties of cyclic quadrilateral ABCD. See whether you can discover several relationships that appear to be true regardless of the size of the circle or the location of A, B, C, and D on the circle. 2. Measure the lengths of the sides and diagonals of quadrilateral ABCD. See whether you can discover a relationship that is always true of these six measurements for all cyclic quadrilaterals. This relationship has been known for 1800 years and is called Ptolemy’s Theorem after Alexandrian mathematician Claudius Ptolemaeus (A.D. 85 to 165). 3. Determine which quadrilaterals from the quadrilateral hierarchy can be cyclic quadrilaterals (Figure 2). 4. Over 1300 years ago, the Hindu mathematician Brahmagupta discovered that the area of a cyclic Figure 2 quadrilateral can be determined by the formula: A = (s – a)(s – b)(s – c)(s – d) where a, b, c, and d are the lengths of the sides of the a + b + c + d quadrilateral and s is the semiperimeter given by s = 2 . Using cyclic quadrilaterals, verify these relationships. -

Foundations for Geometry

Foundations for Geometry 1A Euclidean and Construction Tools 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lab Explore Properties Associated with Points 1-2 Measuring and Constructing Segments 1-3 Measuring and Constructing Angles 1-4 Pairs of Angles 1B Coordinate and Transformation Tools 1-5 Using Formulas in Geometry 1-6 Midpoint and Distance in the Coordinate Plane 1-7 Transformations in the Coordinate Plane Lab Explore Transformations KEYWORD: MG7 ChProj Representations of points, lines, and planes can be seen in the Los Angeles skyline. Skyline Los Angeles, CA 2 Chapter 1 Vocabulary Match each term on the left with a definition on the right. 1. coordinate A. a mathematical phrase that contains operations, numbers, and/or variables 2. metric system of measurement B. the measurement system often used in the United States 3. expression C. one of the numbers of an ordered pair that locates a point on a coordinate graph 4. order of operations D. a list of rules for evaluating expressions E. a decimal system of weights and measures that is used universally in science and commonly throughout the world Measure with Customary and Metric Units For each object tell which is the better measurement. 5. length of an unsharpened pencil 6. the diameter of a quarter __1 __3 __1 7 2 in. or 9 4 in. 1 m or 2 2 cm 7. length of a soccer field 8. height of a classroom 100 yd or 40 yd 5 ft or 10 ft 9. height of a student’s desk 10. length of a dollar bill 30 in.