08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E

BOOK REVIEW Einstein’s Italian Mathematicians: Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E. Rowe Einstein’s Italian modern Italy. Nor does the author shy away from topics Mathematicians: like how Ricci developed his absolute differential calculus Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the as a generalization of E. B. Christoffel’s (1829–1900) work Birth of General Relativity on quadratic differential forms or why it served as a key By Judith R. Goodstein tool for Einstein in his efforts to generalize the special theory of relativity in order to incorporate gravitation. In This delightful little book re- like manner, she describes how Levi-Civita was able to sulted from the author’s long- give a clear geometric interpretation of curvature effects standing enchantment with Tul- in Einstein’s theory by appealing to his concept of parallel lio Levi-Civita (1873–1941), his displacement of vectors (see below). For these and other mentor Gregorio Ricci Curbastro topics, Goodstein draws on and cites a great deal of the (1853–1925), and the special AMS, 2018, 211 pp. 211 AMS, 2018, vast secondary literature produced in recent decades by the world that these and other Ital- “Einstein industry,” in particular the ongoing project that ian mathematicians occupied and helped to shape. The has produced the first 15 volumes of The Collected Papers importance of their work for Einstein’s general theory of of Albert Einstein [CPAE 1–15, 1987–2018]. relativity is one of the more celebrated topics in the history Her account proceeds in three parts spread out over of modern mathematical physics; this is told, for example, twelve chapters, the first seven of which cover episodes in [Pais 1982], the standard biography of Einstein. -

The Birth of Hyperbolic Geometry Carl Friederich Gauss

The Birth of Hyperbolic Geometry Carl Friederich Gauss • There is some evidence to suggest that Gauss began studying the problem of the fifth postulate as early as 1789, when he was 12. We know in letters that he had done substantial work of the course of many years: Carl Friederich Gauss • “On the supposition that Euclidean geometry is not valid, it is easy to show that similar figures do not exist; in that case, the angles of an equilateral triangle vary with the side in which I see no absurdity at all. The angle is a function of the side and the sides are functions of the angle, a function which, of course, at the same time involves a constant length. It seems somewhat of a paradox to say that a constant length could be given a priori as it were, but in this again I see nothing inconsistent. Indeed it would be desirable that Euclidean geometry were not valid, for then we should possess a general a priori standard of measure.“ – Letter to Gerling, 1816 Carl Friederich Gauss • "I am convinced more and more that the necessary truth of our geometry cannot be demonstrated, at least not by the human intellect to the human understanding. Perhaps in another world, we may gain other insights into the nature of space which at present are unattainable to us. Until then we must consider geometry as of equal rank not with arithmetic, which is purely a priori, but with mechanics.“ –Letter to Olbers, 1817 Carl Friederich Gauss • " There is no doubt that it can be rigorously established that the sum of the angles of a rectilinear triangle cannot exceed 180°. -

Circle Theorems

Circle theorems A LEVEL LINKS Scheme of work: 2b. Circles – equation of a circle, geometric problems on a grid Key points • A chord is a straight line joining two points on the circumference of a circle. So AB is a chord. • A tangent is a straight line that touches the circumference of a circle at only one point. The angle between a tangent and the radius is 90°. • Two tangents on a circle that meet at a point outside the circle are equal in length. So AC = BC. • The angle in a semicircle is a right angle. So angle ABC = 90°. • When two angles are subtended by the same arc, the angle at the centre of a circle is twice the angle at the circumference. So angle AOB = 2 × angle ACB. • Angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal. This means that angles in the same segment are equal. So angle ACB = angle ADB and angle CAD = angle CBD. • A cyclic quadrilateral is a quadrilateral with all four vertices on the circumference of a circle. Opposite angles in a cyclic quadrilateral total 180°. So x + y = 180° and p + q = 180°. • The angle between a tangent and chord is equal to the angle in the alternate segment, this is known as the alternate segment theorem. So angle BAT = angle ACB. Examples Example 1 Work out the size of each angle marked with a letter. Give reasons for your answers. Angle a = 360° − 92° 1 The angles in a full turn total 360°. = 268° as the angles in a full turn total 360°. -

And Are Lines on Sphere B That Contain Point Q

11-5 Spherical Geometry Name each of the following on sphere B. 3. a triangle SOLUTION: are examples of triangles on sphere B. 1. two lines containing point Q SOLUTION: and are lines on sphere B that contain point Q. ANSWER: 4. two segments on the same great circle SOLUTION: are segments on the same great circle. ANSWER: and 2. a segment containing point L SOLUTION: is a segment on sphere B that contains point L. ANSWER: SPORTS Determine whether figure X on each of the spheres shown is a line in spherical geometry. 5. Refer to the image on Page 829. SOLUTION: Notice that figure X does not go through the pole of ANSWER: the sphere. Therefore, figure X is not a great circle and so not a line in spherical geometry. ANSWER: no eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 11-5 Spherical Geometry 6. Refer to the image on Page 829. 8. Perpendicular lines intersect at one point. SOLUTION: SOLUTION: Notice that the figure X passes through the center of Perpendicular great circles intersect at two points. the ball and is a great circle, so it is a line in spherical geometry. ANSWER: yes ANSWER: PERSEVERANC Determine whether the Perpendicular great circles intersect at two points. following postulate or property of plane Euclidean geometry has a corresponding Name two lines containing point M, a segment statement in spherical geometry. If so, write the containing point S, and a triangle in each of the corresponding statement. If not, explain your following spheres. reasoning. 7. The points on any line or line segment can be put into one-to-one correspondence with real numbers. -

20. Geometry of the Circle (SC)

20. GEOMETRY OF THE CIRCLE PARTS OF THE CIRCLE Segments When we speak of a circle we may be referring to the plane figure itself or the boundary of the shape, called the circumference. In solving problems involving the circle, we must be familiar with several theorems. In order to understand these theorems, we review the names given to parts of a circle. Diameter and chord The region that is encompassed between an arc and a chord is called a segment. The region between the chord and the minor arc is called the minor segment. The region between the chord and the major arc is called the major segment. If the chord is a diameter, then both segments are equal and are called semi-circles. The straight line joining any two points on the circle is called a chord. Sectors A diameter is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. It is, therefore, the longest possible chord of a circle. In the diagram, O is the center of the circle, AB is a diameter and PQ is also a chord. Arcs The region that is enclosed by any two radii and an arc is called a sector. If the region is bounded by the two radii and a minor arc, then it is called the minor sector. www.faspassmaths.comIf the region is bounded by two radii and the major arc, it is called the major sector. An arc of a circle is the part of the circumference of the circle that is cut off by a chord. -

Riemann's Contribution to Differential Geometry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematics 9 (1982) l-18 RIEMANN'S CONTRIBUTION TO DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY BY ESTHER PORTNOY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, URBANA, IL 61801 SUMMARIES In order to make a reasonable assessment of the significance of Riemann's role in the history of dif- ferential geometry, not unduly influenced by his rep- utation as a great mathematician, we must examine the contents of his geometric writings and consider the response of other mathematicians in the years immedi- ately following their publication. Pour juger adkquatement le role de Riemann dans le developpement de la geometric differentielle sans etre influence outre mesure par sa reputation de trks grand mathematicien, nous devons &udier le contenu de ses travaux en geometric et prendre en consideration les reactions des autres mathematiciens au tours de trois an&es qui suivirent leur publication. Urn Riemann's Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Differentialgeometrie richtig einzuschZtzen, ohne sich von seinem Ruf als bedeutender Mathematiker iiberm;issig beeindrucken zu lassen, ist es notwendig den Inhalt seiner geometrischen Schriften und die Haltung zeitgen&sischer Mathematiker unmittelbar nach ihrer Verijffentlichung zu untersuchen. On June 10, 1854, Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann read his probationary lecture, "iber die Hypothesen welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen," before the Philosophical Faculty at Gdttingen ill. His biographer, Dedekind [1892, 5491, reported that Riemann had worked hard to make the lecture understandable to nonmathematicians in the audience, and that the result was a masterpiece of presentation, in which the ideas were set forth clearly without the aid of analytic techniques. -

Foundations of Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Foundations of geometry Lawrence Michael Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Lawrence Michael, "Foundations of geometry" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3419 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Approved by: 3)?/08 Murran, Committee Chair Date _ ommi^yee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member 1 Peter Williams, Chair, Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics iii Abstract In this paper, a brief introduction to the history, and development, of Euclidean Geometry will be followed by a biographical background of David Hilbert, highlighting significant events in his educational and professional life. In an attempt to add rigor to the presentation of Geometry, Hilbert defined concepts and presented five groups of axioms that were mutually independent yet compatible, including introducing axioms of congruence in order to present displacement. -

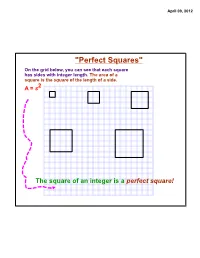

"Perfect Squares" on the Grid Below, You Can See That Each Square Has Sides with Integer Length

April 09, 2012 "Perfect Squares" On the grid below, you can see that each square has sides with integer length. The area of a square is the square of the length of a side. A = s2 The square of an integer is a perfect square! April 09, 2012 Square Roots and Irrational Numbers The inverse of squaring a number is finding a square root. The square-root radical, , indicates the nonnegative square root of a number. The number underneath the square root (radical) sign is called the radicand. Ex: 16 = 121 = 49 = 144 = The square of an integer results in a perfect square. Since squaring a number is multiplying it by itself, there are two integer values that will result in the same perfect square: the positive integer and its opposite. 2 Ex: If x = (perfect square), solutions would be x and (-x)!! Ex: a2 = 25 5 and -5 would make this equation true! April 09, 2012 If an integer is NOT a perfect square, its square root is irrational!!! Remember that an irrational number has a decimal form that is non- terminating, non-repeating, and thus cannot be written as a fraction. For an integer that is not a perfect square, you can estimate its square root on a number line. Ex: 8 Since 22 = 4, and 32 = 9, 8 would fall between integers 2 and 3 on a number line. -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 April 09, 2012 Approximate where √40 falls on the number line: Approximate where √192 falls on the number line: April 09, 2012 Topic Extension: Simplest Radical Form Simplify the radicand so that it has no more perfect-square factors. -

Positional Astronomy Coordinate Systems

Positional Astronomy Observational Astronomy 2019 Part 2 Prof. S.C. Trager Coordinate systems We need to know where the astronomical objects we want to study are located in order to study them! We need a system (well, many systems!) to describe the positions of astronomical objects. The Celestial Sphere First we need the concept of the celestial sphere. It would be nice if we knew the distance to every object we’re interested in — but we don’t. And it’s actually unnecessary in order to observe them! The Celestial Sphere Instead, we assume that all astronomical sources are infinitely far away and live on the surface of a sphere at infinite distance. This is the celestial sphere. If we define a coordinate system on this sphere, we know where to point! Furthermore, stars (and galaxies) move with respect to each other. The motion normal to the line of sight — i.e., on the celestial sphere — is called proper motion (which we’ll return to shortly) Astronomical coordinate systems A bit of terminology: great circle: a circle on the surface of a sphere intercepting a plane that intersects the origin of the sphere i.e., any circle on the surface of a sphere that divides that sphere into two equal hemispheres Horizon coordinates A natural coordinate system for an Earth- bound observer is the “horizon” or “Alt-Az” coordinate system The great circle of the horizon projected on the celestial sphere is the equator of this system. Horizon coordinates Altitude (or elevation) is the angle from the horizon up to our object — the zenith, the point directly above the observer, is at +90º Horizon coordinates We need another coordinate: define a great circle perpendicular to the equator (horizon) passing through the zenith and, for convenience, due north This line of constant longitude is called a meridian Horizon coordinates The azimuth is the angle measured along the horizon from north towards east to the great circle that intercepts our object (star) and the zenith. -

Spherical Geometry

987023 2473 < % 52873 52 59 3 1273 ¼4 14 578 2 49873 3 4 7∆��≌ ≠ 3 δ � 2 1 2 7 5 8 4 3 23 5 1 ⅓β ⅝Υ � VCAA-AMSI maths modules 5 1 85 34 5 45 83 8 8 3 12 5 = 2 38 95 123 7 3 7 8 x 3 309 �Υβ⅓⅝ 2 8 13 2 3 3 4 1 8 2 0 9 756 73 < 1 348 2 5 1 0 7 4 9 9 38 5 8 7 1 5 812 2 8 8 ХФУШ 7 δ 4 x ≠ 9 3 ЩЫ � Ѕ � Ђ 4 � ≌ = ⅙ Ё ∆ ⊚ ϟϝ 7 0 Ϛ ό ¼ 2 ύҖ 3 3 Ҧδ 2 4 Ѽ 3 5 ᴂԅ 3 3 Ӡ ⍰1 ⋓ ӓ 2 7 ӕ 7 ⟼ ⍬ 9 3 8 Ӂ 0 ⤍ 8 9 Ҷ 5 2 ⋟ ҵ 4 8 ⤮ 9 ӛ 5 ₴ 9 4 5 € 4 ₦ € 9 7 3 ⅘ 3 ⅔ 8 2 2 0 3 1 ℨ 3 ℶ 3 0 ℜ 9 2 ⅈ 9 ↄ 7 ⅞ 7 8 5 2 ∭ 8 1 8 2 4 5 6 3 3 9 8 3 8 1 3 2 4 1 85 5 4 3 Ӡ 7 5 ԅ 5 1 ᴂ - 4 �Υβ⅓⅝ 0 Ѽ 8 3 7 Ҧ 6 2 3 Җ 3 ύ 4 4 0 Ω 2 = - Å 8 € ℭ 6 9 x ℗ 0 2 1 7 ℋ 8 ℤ 0 ∬ - √ 1 ∜ ∱ 5 ≄ 7 A guide for teachers – Years 11 and 12 ∾ 3 ⋞ 4 ⋃ 8 6 ⑦ 9 ∭ ⋟ 5 ⤍ ⅞ Geometry ↄ ⟼ ⅈ ⤮ ℜ ℶ ⍬ ₦ ⍰ ℨ Spherical Geometry ₴ € ⋓ ⊚ ⅙ ӛ ⋟ ⑦ ⋃ Ϛ ό ⋞ 5 ∾ 8 ≄ ∱ 3 ∜ 8 7 √ 3 6 ∬ ℤ ҵ 4 Ҷ Ӂ ύ ӕ Җ ӓ Ӡ Ҧ ԅ Ѽ ᴂ 8 7 5 6 Years DRAFT 11&12 DRAFT Spherical Geometry – A guide for teachers (Years 11–12) Andrew Stewart, Presbyterian Ladies’ College, Melbourne Illustrations and web design: Catherine Tan © VCAA and The University of Melbourne on behalf of AMSI 2015. -

Points, Lines, and Planes a Point Is a Position in Space. a Point Has No Length Or Width Or Thickness

Points, Lines, and Planes A Point is a position in space. A point has no length or width or thickness. A point in geometry is represented by a dot. To name a point, we usually use a (capital) letter. A A (straight) line has length but no width or thickness. A line is understood to extend indefinitely to both sides. It does not have a beginning or end. A B C D A line consists of infinitely many points. The four points A, B, C, D are all on the same line. Postulate: Two points determine a line. We name a line by using any two points on the line, so the above line can be named as any of the following: ! ! ! ! ! AB BC AC AD CD Any three or more points that are on the same line are called colinear points. In the above, points A; B; C; D are all colinear. A Ray is part of a line that has a beginning point, and extends indefinitely to one direction. A B C D A ray is named by using its beginning point with another point it contains. −! −! −−! −−! In the above, ray AB is the same ray as AC or AD. But ray BD is not the same −−! ray as AD. A (line) segment is a finite part of a line between two points, called its end points. A segment has a finite length. A B C D B C In the above, segment AD is not the same as segment BC Segment Addition Postulate: In a line segment, if points A; B; C are colinear and point B is between point A and point C, then AB + BC = AC You may look at the plus sign, +, as adding the length of the segments as numbers. -

Foundations for Geometry

Foundations for Geometry 1A Euclidean and Construction Tools 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lab Explore Properties Associated with Points 1-2 Measuring and Constructing Segments 1-3 Measuring and Constructing Angles 1-4 Pairs of Angles 1B Coordinate and Transformation Tools 1-5 Using Formulas in Geometry 1-6 Midpoint and Distance in the Coordinate Plane 1-7 Transformations in the Coordinate Plane Lab Explore Transformations KEYWORD: MG7 ChProj Representations of points, lines, and planes can be seen in the Los Angeles skyline. Skyline Los Angeles, CA 2 Chapter 1 Vocabulary Match each term on the left with a definition on the right. 1. coordinate A. a mathematical phrase that contains operations, numbers, and/or variables 2. metric system of measurement B. the measurement system often used in the United States 3. expression C. one of the numbers of an ordered pair that locates a point on a coordinate graph 4. order of operations D. a list of rules for evaluating expressions E. a decimal system of weights and measures that is used universally in science and commonly throughout the world Measure with Customary and Metric Units For each object tell which is the better measurement. 5. length of an unsharpened pencil 6. the diameter of a quarter __1 __3 __1 7 2 in. or 9 4 in. 1 m or 2 2 cm 7. length of a soccer field 8. height of a classroom 100 yd or 40 yd 5 ft or 10 ft 9. height of a student’s desk 10. length of a dollar bill 30 in.