An ESSAY on the PRINCIPLES of CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE, Illustrated by Numerous Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

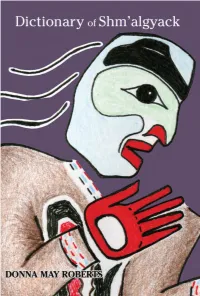

Tsimshian Dictionary

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

Transcript by Rev.Com Had Seating for 100 People, and Would Have Been the Emergency Senate Chamber

Joanne Freeman: Major funding for Back Story is provided by an anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Virginia, and the Robert and Joseph Cornel Memorial Foundation. Ed Ayers: From Virginia Humanities, this is Back Story. Brian Balogh: Welcome to Back Story, the show that explains the history behind today's headlines. I'm Brian Balogh. Ed Ayers: I'm Ed Ayers. Joanne Freeman: I'm Joanne Freeman. Ed Ayers: If you're new to the podcast, we're all historians. Each week, we explore the history of one topic that's been in the news. Joanne Freeman: Now, picture a luxury hotel. Attentive staff buzz around serving drinks to thirsty golfers who've just come in after playing 18 holes; but behind a false wall, there's a blast door intended to keep out radiation from a nuclear bomb. Nobody who works here knows, but this is where the American president, senators, and congressmen will hide out if America comes under attack by nuclear weapons. Sounds like a James Bond movie, right? Joanne Freeman: We're going to start off today by going underground to a secret facility standing by not far from here. Garrett Graff: ... I ever went to was the Greenbrier bunker, which would have been the congressional bunker and relocation facility during the course of the Cold War. Brian Balogh: This is the writer and historian, Garrett Graff. Garrett Graff: It was this bunker hidden under this very fine golf resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. The resort is still used as a annual congressional retreat. -

Nativity Scene Marks Christinas Santa Clans Parade Saturday Lots

LEDGER ENTRIES SHORT DAYS FIFTY-FIFTH YEAR LOWELL, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, DEC. 11, 1947 NUMBER 32 Now that the big giune hunters We have come close to the time have ail returned home, It !• claim- of year when the calendar shows ed that the hamburg. ia playing neo- the shortest days. The sun Is far ond fiddle to the deerburg. Said to Mrs. Gerald Staal Lawrence Ridgway away from us. He is flooding the be real tavory. Nativity Scene Santa Clans Parade Saturday South American countries with his — The HUlto — Passes at Age 32 Military Funeral Court's Decision bright sunshine. They revel In Mrs. Gerald Staal, 32, who was their own summer, and are happy The Lowell Board of Trade In in his golden light. The land of ths holding an old-time Chrtotmas taken to Osteopathic hospital in Orand Rapids late Tuesday after- rhumba and the tango flourishes party this Thursday evening at six Marks Christinas Lots of Fun For Young And Old Would Aid Lowell under his stimulating rays. o'clock at South Boston Orange noon, passed away about 1:30 Wed- hall. The ladies of the Orange will nesday morning. She had been in Plans for the first annual Santa Claus parade to be staged Satur- Legislature May Try To The sunlight now strikes us at a serve a turkey dinner which will be Hour Program Each Night poor health for some time. She is day, December 13 at 3 p. m. arc complete and the event promises very slanting angle, and there Is followed by a grand program and survived by the husband, a son Jack to hold plenty of fun for young snd old. -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield. -

Bunn Broccardo Sotomayor

8 BUNN BROCCARDO SOTOMAYOR RATED T 0 0 8 1 1 $3.99US MARVEL.COM 7 59606 08344 2 Known to the world as Kid Kaiju, Kei Kawade has the Inhuman ability to summon and create monsters simply by drawing them. JOINED BY CREATURE-EXPERT Elsa Bloodstone, Kid Kaiju AND HIS TEAM protect the world from monsters gone bad. kid kaiju elsa aegis hi-vo mekara scragg slizzik bloodstone Kei has been having nightmares of creatures from another universe--and when he wakes up, he realizes he’s been sleep- drawing them, too! And now he’s accidentally summoned one of these creatures--a monster that looks similar to Fin Fang Foom! The creature wants to take Kei back to his home universe and use Kei as a conduit to bring other monsters through…their plan? Take over our universe! When Kei summoned his monsters to fight this creature, they were struck down. How do you deal with an alternate-universe Fin Fang Foom? Well, summon the original Foom to do battle with this evil incarnation of himself! Cullen Bunn Andrea Broccardo Chris Sotomayor Writer artist color artist VC’s Travis Lanham r.b. silva & Nolan Woodard letterer cover art Christina Harrington mark paniccia editor senior editor axel alonso joe quesada dan buckley alan fine Editor in chief chief creative officer pRESIDENT executive producer MONSTERS UNLEASHED No. 8, January 2018. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. -

Kirby Interview Steve Rude & Mike Mignola Stan Lee's Words Fantastic Four #49 Pencils Darkseid, Red Skull, Doctor Doom, At

THE $5.95 In The US ISSUE #22, DEC. 1998 A 68- PAGE COLLECTOR ISSUE ON KIRBY’S VILLAINS! AN UNPUBLISHED Kirby Interview INTERVIEWS WITH Steve Rude & Mike Mignola COMPARING KIRBY’S MARGIN NOTES TO Stan Lee’s Words STUNNING UNINKED Fantastic Four #49 Pencils SPECIAL FEATURES: Darkseid, Red Skull, Doctor Doom, Atlas Monsters, . s Yellow Claw, n e v e t S e & Others v a D & y b r THE GENESIS OF i K k c a J King Kobra © k r o w t r A . c Unpublished Art n I , t INCLUDING PENCIL n e PAGES BEFORE m n i a THEY WERE INKED, t r e t AND MUCH MORE!! n E l e v r a M NOMINATED FOR TWO 1998 M T EISNER r e AWARDS f r INCLUDING “BEST u S COMICS-RELATED r PUBLICATION” e v l i S 1998 HARVEY AWARDS NOMINEE , m “BEST BIOGRAPHICAL, HISTORICAL o OR JOURNALISTIC PRESENTATION” o D . r D THE ONLY ’ZINE AUTHORIZED BY THE Issue #22 Contents: THE KIRBY ESTATE Morals and Means ..............................4 (the hows and whys of Jack’s villains) Fascism In The Fourth World .............5 (Hitler meets Darkseid) So Glad To Be Sooo Baaadd! ..............9 (the top ten S&K Golden Age villains) ISSUE #22, DEC. 1998 COLLECTOR At The Mercy Of The Yellow Claw! ....14 (the brief but brilliant 1950s series) Jack Kirby Interview .........................17 (a previously unpublished chat) What Truth Lay Beneath The Mask? ..22 (an analysis of Victor Von Doom) Madame Medusa ..............................24 (the larcenous lady of the living locks!) Mike Mignola Interview ...................25 (Hellboy’s father speaks) Saguur ..............................................30 (the -

Book Bin Order Form

BOOK BIN ORDER FORM MARVEL BOOK BINS New comic book & graphic novel book bins from ABDO! Each collection includes a free 2-handled bin with cover, a poster, and a set of bookmarks. Free Marvel cardboard standup with order of two bins or more! Book bins are perfect for afterschool programs, ELL programs, Special Education, book clubs, summer reading, libraries, classrooms, and more! Corresponding lesson plans and discussion questions are available with book bin purchase, or with a custom bin or series order of $750.00 or more. For questions on bins, email [email protected] MARVEL COLLECTION BINS Grades 2-8 Collection bins are perfect for any setting! With one copy of each book, these bins will help you start your graphic novel collection or add more popular graphic novels to your collection. With reinforced bindings, these books will withstand the circulation they will get in your school, library, program, or club! These collection bins include between 33-51 books, 1 copy of each book. Spotlight © 2006-2012 - Reinforced Library Binding AVENGERS ASSEMBLE! COLLECTION BIN All the characters kids love from the hit movie placed in one exciting and irresistible bin! This collection bin includes 51 books, 1 copy of each book. Series included are: The Avengers (12 titles), The Hulk (8 titles), Captain America (5 titles), Captain America: The Korvac Saga (4 titles), Iron Man (12 titles), Thor, Son of Asgard (6 titles), and Iron Man and Thor (4 titles). Each Bin: $1,234.71 (List) / $864.45 (School/Library) Qty Item # Title ISBN ATOS __________ B102-7 AVENGERS ASSEMBLE! COLLECTION BIN 978-1-61479-102-7 2.2-4.2 SPIDER-MAN SPECTACULAR! COLLECTION BIN A great collection of adventures starring kids’ favorite superhero! This collection bin includes 46 books, 1 copy of each book. -

The Magazine for Students of Film and Media Studies

THE MAGAZINE FOR STUDENTS OF FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES APRIL 2018 ISSUE 64 GLOW PAN’S LABYRINTH SUNRISE CONTINUITY EDITING THE LAST JEDI DO THE RIGHT THING I, DANIEL BLAKE JUDITH BUTLER SIXTEEN YEARS OF MEDIAMAG: A REFLECTION MM64 artwork cover.indd 1 23/03/2018 16:41 Contents 04 Making the Most of 26 Critical Hit! MediaMag Caroline Bayley explains how a perfect MediaMagazine is published storm of technological developments by the English and Media 06 Sixteen years of led to the enormous success of online Centre, a non-profit making MediaMagazine: a history role-playing game, Critical Role. organisation. The Centre of the media in 64 issues publishes a wide range of Jenny Grahame looks 30 It’s personal: the presentation classroom materials and back over her 16 years as of masculinity in John Wick runs courses for teachers. Editor of MediaMagazine. Fay Jessop considers an emerging If you’re studying English franchise featuring a stereotypical at A Level, look out for 10 Doing the Right Thing hard-man tempered by grief in a emagazine, also published Nick Lacey looks at the more complex representation of by the Centre. enduring success of Lee’s masculinity than you might expect. indie movie focusing on the lives African Americans 34 G.L.O.W in 80s Brooklyn. Is GLOW the ultimate feminist text, or just another male gaze media 14 Studying Sunrise product designed to objectify women? Caroline Birks introduces Claire Kennedy investigates. this new Eduqas set text, a lesser-known masterpiece from F. W. Murnau. 18 I, Daniel Blake: A Case Study in Disruptive Marketing Michelle Thomason explains how the politically proactive marketing of this powerful The English and Media Centre film has amplified its activist 18 Compton Terrace message for audiences. -

Jack Kirby Collector #77•Summer 2019•$10.95

THE BREAK OUT DDT AND RUN FOR YOUR LIFE! IT’S THE AND BUGS ISSUE JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #77•SUMMER 2019•$10.95 with ERIC POWELL•MICHAEL CHO•MARK EVANIER•SEAN KLEEFELD•BARRY FORSHAW•ADAM McGOVERN•NORRIS BURROUGHS•SHANE FOLEY•JERRY BOYD 4 5 6 3 0 0 8 5 6 2 8 1 STARRING JACK KIRBY•DIRECTED BY JOHN MORROW•FEATURING RARE KIRBY ARTWORK•A TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING RELEASE Monster, Forager TM & © DC ComicsNew • Goom Gods TM TM & ©& Marvel © DC Characters,Comics. Inc. • Lightning Lady TM & © Jack Kirby Estate Contents THE Monsters & Bugs! OPENING SHOT ................2 ( something’s bugging the editor) FOUNDATIONS ................4 (S&K show the monsters inside us) ISSUE #77, SUMMER 2019 RETROSPECTIVE ..............12 Collector (from Vandoom to Von Doom) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY .....23 (you recall Giganto, don’t you?) KIRBY KINETICS ..............25 (the FF’s strange evolution) INFLUENCEES ................30 (cover inker Eric Powell speaks) GALLERY 1 ..................34 (monsters, in pencil) HORRORFLIK ................42 (Jack’s ill-fated Empire Pictures deal) KIRBY OBSCURA .............46 (vintage 1950s monster stories) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM .........48 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) POW!ER ....................49 (two monster Kirby techniques) UNEXPLAINED ...............51 (three major myths of Kirby’s) BOYDISMS ...................54 (monsters, all the way back to the ’40s) KIRBY AS A GENRE ...........64 (Michael Cho on his Kirby influences) ANTI-MAN ..................68 (we go foraging for bugs) GALLERY 2 ..................72 (the bugs attack!) UNDISCOVERED -

EL UNIVERSO CROMÁTICO DE Mccoy, Medusa Melter Mentallo Mephisto Merlin Norton

El color de su creatividad Colores predominantes Stan Lee presentó al mundo personajes notables por su complejidad y realismo. Creó íconos del cómic como: Spider-Man, X-Men, Iron Man, Thor o Avengers, casi siempre acompañado de los dibujantes Steve Ditko y Jack Kirby. En el siguiente desglose te presentamos los dos colores Desgl se Nombre del predonimantes en el diseño de cada una de sus creaciones. personaje Abomination Absorbing Aged Agent X Aggamon Agon Aireo Allan, Liz Alpha Amphibion Ancient One Anelle Ant-Man Ares Avengers* Awesome Man Genghis Primitive Android Balder Batroc the Beast Beetle Behemoth Black Bolt Black Knight Black Black Widow Blacklash Blastaar Blizzard Blob Bluebird Boomerang Bor Leaper Panther Betty Brant Brother Blockbuster Blonde Brotherhood Burglar Captain Captain Carter, Chameleon Circus Clea Clown Cobra Cohen, Izzy Collector Voodoo Phantom of Mutants** Barracuda Marvel Sharon of Crime** Crime Crimson Crystal Cyclops Daredevil Death- Dernier, Destroyer Diablo Dionysus Doctor Doctor Dormammu Dragon Man Dredmund Dum Dum Master Dynamo Stalker Jacques Doom Faustus the Druid Dugan Eel Egghead Ego the Electro Elektro Enchantress Enclave** Enforcers** Eternity Executioner Fafnir Falcon Fancy Dan Fandral Fantastic Farley Living Planet Four** Stillwell Fenris Wolf Fin Fang Fisk, Richard Fisk, Fixer Foster, Bill Frederick Freak Frigga Frightful Fury, Nick Galactus Galaxy Gargan, Mac Gargoyle Gibbon Foom Vanessa Foswell Four** Master Gladiator Googam Goom Gorgilla Gorgon Governator Great Green Goblin Gregory Grey Grey, Elaine Grey, Dr. Grey, Jean Grizzly Groot Growing Gambonnos** Gideon Gargoyle John Man The Guardian H.E.R.B.I.E. Harkness, Hate Monger Hawkeye Heimdall Hela Hera Herald of Hercules High Happy Hogun Hulk Human Human Project** Agatha Galactus Evolutionary Hogan Cannonball Torch Iceman Idunn Immortus Imperial Impossible Inhumans** Invisible Iron Man Jackal John J. -

PHYSICAL THERAPY PRACTICE the Magazine of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, APTA

2019 / volume 31 / number 1 ORTHOPAEDIC PHYSICAL THERAPY PRACTICE The magazine of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, APTA FEATURE: Effect of Eccentric Exercises at the Knee with Hip Muscle Strengthening to Treat Patellar Tendinopathy in Active Duty Military Personnel 6938_OP_Jan.indd 501 12/17/18 12:55 PM 6938_OP_Jan.indd 502 12/17/18 12:55 PM ORTHOPAEDIC PHYSICAL THERAPY PRACTICE The magazine of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, APTA In this issue Regular features 8 Effect of ccentricE Exercises at the Knee with Hip Muscle Strengthening to 3 President's Corner Treat Patellar Tendinopathy in Active Duty Military Personnel: A Randomized Pilot 5 Editor’s Note Kerry MacDonald, Johnathan Day, Carol Dionne 6 New Year, New Editor 18 Manual Therapy and Exercise in Treatment of a Patient with 39 Wooden Book Reviews Cervical Radiculopathy Robert Boyles, Andrew Didricksen, Justin Higa, Daniel Kobayashi 40 Occupational Health SIG Newsletter 24 Manual Therapy Application in the Management of Baastrup’s Disease: 42 Performing Arts SIG Newsletter A Case Report Douglas Steele, Mark Kosier 49 Foot & Ankle SIG Newsletter 50 Pain SIG Newsletter 30 Clinical Application: Physical Examination Procedure to Assess Hip Joint Synovitis/Effusion 54 Imaging SIG Newsletter Damien Howell 55 Orthopaedic Residency/Fellowship 36 Rehabilitation Outcomes Following Primary vs Secondary Repair of SIG Newsletter Ruptured Tibialis Anterior Tendon: A Report of Two Cases Susan Kelvasa, Prarthana Gururaj 57 Animal Rehabilitation SIG Newsletter 60 Index to Advertisers OPTP Mission Publication Staff Managing Editor & Advertising Editor To serve as an advocate and Sharon L. Klinski Christopher Hughes, PT, PhD, OCS resource for the practice of Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Associate Editor Orthopaedic Physical Therapy by 2920 East Ave So, Suite 200 Rita Shapiro, PT, MA, DPT La Crosse, Wisconsin 54601 fostering quality patient/client care 800-444-3982 x 2020 Book Review Editor and promoting professional growth. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-ONE $9 95 IN THE US Contents THE NEW Everything Goes! OPENING SHOT . 2 (with hopefully no reruns...) UNDER THE COVERS . 3 (behind the scenes of covers for this issue and last ) JACK F.A.Q. s . 4 ISSUE #51, FALL 2008 Collector (Mark Evanier on Jacks Schiff and Kirby, plus Schiff discusses Kirby, and Roz discusses Schiff) FOUNDATIONS . 9 (Jack served two Masters ) SEARCHABILITY . 12 (Tom Stewart, our Comics Savant, looks for & finds a Kirby Planet) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . 14 (the 1970s Sandman really woke things up, design-wise) TOOLTIME . 15 (a pointed article on Jack’s pencils) KIRBY ENCOUNTERS . 16 (a close call with Jack) COVER STORY . 17 (Kirby cover redux) GALLERY . 18 (Atlas monsters, before & after) ADAM M cGOVERN . 44 (robots and zombies both love brains...) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . 47 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) COVERING IT ALL . 48 (a Timely decision about when S&K had Hitler covered ) STREETWISE . 50 (Kirby debunks some urban legends) ORIGINAL ART-IFACTS . 52 (Thor #149 cover original art) KIRBY OBSCUR A . 53 (Barry Forshaw on some Atlas Monsters) INFLUENCEES . 54 (short but sweet interviews with Jim Lee and Adam Hughes) GRINDSTONES . 56 (examining the Kirby work ethic) NUTS & BOLTS . 59 (dancing the Kirby method) LEGAL-EASE . 60 (the legal standing on Kirby and copyrights) TRIBUTE . 62 (the 2007 Kirby Tribute Panel, featuring Neil Gaiman, Darwyn Cooke, Erik Larsen, and Kirby attorney Paul Levine) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . 76 PARTING SHOT . 80 Front cover inks: FRANK GIACOIA Front cover colors: JACK KIRBY (with thanks to John Fleskes) Back cover paint: PETE VON SHOLLY The Jack Kirby Collector , Vol.