Transcript by Rev.Com Had Seating for 100 People, and Would Have Been the Emergency Senate Chamber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

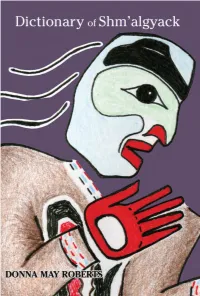

Tsimshian Dictionary

Dictionary of Shm’algyack Donna May Roberts Sealaska Heritage Institute Juneau, Alaska © 2009 by Sealaska Heritage Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 1440401195 EAN-13:9781440401190 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939132 Sealaska Heritage Institute One Sealaska Plaza, Suite 301 Juneau, Alaska 99801 907-463-4844 www.sealaskaheritage.org Printing: Create Space, Scotts Valley, CA, U.S.A. Front cover design: Kathy Dye Front cover artwork: Robert Hoffmann Book design and computational lexicography: Sean M. Burke Copy editing: Suzanne G. Fox, Red Bird Publishing, Inc., Bozeman, MT Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 3 Dictionary of Shm’algyack Shm’algyack to English ................ 7 English to Shm’algyack ............... 67 Dictionary of Shm'algyack - 1 aam verb to be fine, good, well PLURAL: am'aam Shm'algyack to ·Aam wila howyu. I’m feeling good. ·Na sheepg nakshu ashda 'guulda English shada dowl mahlda doctor hla aam wila waald gya'win. My wife was sick the other day but the doctor said she’s aab noun my father good now. ·Yagwa goom wunsh aabdu. My aamggashgaawt verb to be of father is hunting for deer. medium size, of a good size aad noun; verb net; to seine ·Aamggashgaawt ga yeeh. The King PLURAL: ga'aad salmon was of a good size. ·Geegsh Dzon shu aad dm hoyt hla aamhalaayt noun headdress, aadmhoant. John bought a new net mask, regalia, shaman’s mask; shaman for fishing. -

Concept and Types of Tourism

m Tourism: Concept and Types of Tourism m m 1.1 CONCEPT OF TOURISM Tourism is an ever-expanding service industry with vast growth potential and has therefore become one of the crucial concerns of the not only nations but also of the international community as a whole. Infact, it has come up as a decisive link in gearing up the pace of the socio-economic development world over. It is believed that the word tour in the context of tourism became established in the English language by the eighteen century. On the other hand, according to oxford dictionary, the word tourism first came to light in the English in the nineteen century (1811) from a Greek word 'tomus' meaning a round shaped tool.' Tourism as a phenomenon means the movement of people (both within and across the national borders).Tourism means different things to different people because it is an abstraction of a wide range of consumption activities which demand products and services from a wide range of industries in the economy. In 1905, E. Freuler defined tourism in the modem sense of the world "as a phenomena of modem times based on the increased need for recuperation and change of air, the awakened, and cultivated appreciation of scenic beauty, the pleasure in. and the enjoyment of nature and in particularly brought about by the increasing mingling of various nations and classes of human society, as a result of the development of commerce, industry and trade, and the perfection of the means of transport'.^ Professor Huziker and Krapf of the. -

An ESSAY on the PRINCIPLES of CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE, Illustrated by Numerous Cases

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com A N E S S A Y ON THE PRINCIPLES OF CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE, 3Jllugtratûù bp Jßumerotig Cageg. BY WILLIAM WILLS, Esq. Nulla denique est causa, in qua id, quod in judicium venit, ex reorum per sonis, non generum ipsorum universa disputatione quæratur.—Cic. De Oratore. THIRD EDITION. LONDON ; HENRY BUTTERWORTH, 7, FLEET STREET, 3Ìafm 33udí£cIIcr anù 38ubIigbcr. HODGES AND SMITH, GRAFTON STREET, DUBLIN. 1850. BIBLIOTHECA REGIA MONACENSIS. N PRINTED BY RICHARD AND JOHN E. TAYLOR, RED Lion court, FLEET STREET. PR E FA C E TO THE FIRST EDITION. THE most important doctrines of Circumstantial Evidence have been so ably treated in the learned works of Mr. Bentham and Mr. Starkie, that an apology may be thought necessary for this publication. It will however be per ceived, that the design of the following Essay is different in some important particulars from that of either of the above-mentioned authors; and that an attempt has been made to illustrate the subject by the application of many instructive cases, some of which have been compiled from original documents, and others from publications not easily accessible. It has not always been practicable to support the state ment of cases by reference to books of recognised authority, or of an equal degree of credit; but discrimination has uniformly been exercised in the adoption of such state ments; and they have generally been verified by compa rison with contemporaneous and independent accounts. -

Commodification of Cultural Identities And/Or Empowerment of Local Communities: Developing a Route of Nuclear Tourism

SOCIETY. INTEGRATION. EDUCATION Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Volume V, May 25th-26th, 2018. 145-158 COMMODIFICATION OF CULTURAL IDENTITIES AND/OR EMPOWERMENT OF LOCAL COMMUNITIES: DEVELOPING A ROUTE OF NUCLEAR TOURISM Natalija Mažeikienė Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania Eglė Gerulaitienė Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania Šiauliai University, Lithuania Abstract. Research presented in the paper focuses on commodification of cultural identities and community empowerment strategies of cultural tourism in Visaginas. One of challenges in developing tourism is orientation toward profit and commodification of culture, which becomes a problem in regard to practicing authentic identities. The article presents efforts of researchers working in the project EDUATOM to scientifically substantiate construction of new educational nuclear/ atomic tourism route in the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant (INPP) region. The authors discuss what diverse parameters and elements of place identity could be included and represented in the tourism in Visaginas and how community empowerment and involvement of different stakeholders might contribute to practicing various commodification strategies. The article analyses commodification of cultural identities and community empowerment strategies of educational, cultural, nuclear/atomic tourism in Visaginas, using research strategy of case study, including methods of document analysis, conversations (formal and informal) with stakeholders, secondary data analysis, construction of Post-Soviet -

Join Vivian on the Road

10/2017 John Grisham on North Carolina Bookwatch • Rootle’ween • Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Join Vivian on the Road his season, hit the road for some tasty Tadventures with James Beard Award- winning Chef Vivian Howard (and her food truck) as she supports her first cookbook, a 500-page, New York Times bestselling “culinary love letter.” Don’t miss a morsel of A Chef’s Life’s fifth season—new episodes premiere Thursday nights, at 9:30, on UNC-TV, Public Media North Carolina. Photos: Josh Woll aboutUNC-TV CenterPiece is the monthly program guide of UNC-TV, North Carolina’s public media network and broadcast service licensed to the University UNC-TV’s Exciting Fall Line Up! of North Carolina. Contributions are tax deduct- ible to the extent permitted by law. UNC-TV’s central offices and studios are housed in the Make no mistake about it—the key to new programs on Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Communications UNC-TV is you. We know you share our uncompromising Center in Research Triangle Park. standards and value the opportunity to provide the funds that make our public media service second to none. 10 TW Alexander Drive PO Box 14900 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-4900 So when you see this envelope in your mailbox, please 1-919-549-7000 or 1-800-906-5050 send your special donation to UNC-TV today and keep UNC-TV network stations are: more great programs coming your way. Contribute Asheville WUNF-TV securely online at unctv.org/programs. Canton/Waynesville WUNW-TV Chapel Hill/Raleigh/Durham WUNC-TV Charlotte/Concord WUNG-TV Thank you for -

Nativity Scene Marks Christinas Santa Clans Parade Saturday Lots

LEDGER ENTRIES SHORT DAYS FIFTY-FIFTH YEAR LOWELL, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, DEC. 11, 1947 NUMBER 32 Now that the big giune hunters We have come close to the time have ail returned home, It !• claim- of year when the calendar shows ed that the hamburg. ia playing neo- the shortest days. The sun Is far ond fiddle to the deerburg. Said to Mrs. Gerald Staal Lawrence Ridgway away from us. He is flooding the be real tavory. Nativity Scene Santa Clans Parade Saturday South American countries with his — The HUlto — Passes at Age 32 Military Funeral Court's Decision bright sunshine. They revel In Mrs. Gerald Staal, 32, who was their own summer, and are happy The Lowell Board of Trade In in his golden light. The land of ths holding an old-time Chrtotmas taken to Osteopathic hospital in Orand Rapids late Tuesday after- rhumba and the tango flourishes party this Thursday evening at six Marks Christinas Lots of Fun For Young And Old Would Aid Lowell under his stimulating rays. o'clock at South Boston Orange noon, passed away about 1:30 Wed- hall. The ladies of the Orange will nesday morning. She had been in Plans for the first annual Santa Claus parade to be staged Satur- Legislature May Try To The sunlight now strikes us at a serve a turkey dinner which will be Hour Program Each Night poor health for some time. She is day, December 13 at 3 p. m. arc complete and the event promises very slanting angle, and there Is followed by a grand program and survived by the husband, a son Jack to hold plenty of fun for young snd old. -

Post-Nuclear Monuments, Museums, and Gardens

Post~nuclear Monuments, Museums, and Gardens * MIRA ENGLER INTRODUCTION Mira Engler, Associate Professor of Lanrucape Architecture at Iowa ARKED BY THE SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY of atomic energy, the nuclear age, which State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, spans the twentieth century, has changed the nature of culture as well as M United States of America. l the landscape. Vast, secret landscapes play host to nuclear arms and commercial Email: [email protected] energy producers.2 Nuclear sites concern not only scientists and politicians, but also environmental designers/artists. The need to evoke a cultural discourse, protect future generations, reveal or conceal radioactive burial sites and recycle retired installations engenders our participation. How do we intersect with these hellish places? Do we have a potent role in addressing this conundrum? In what follows, I confront the consumption and design of today's most daunting places - the landscapes of nuclear material production, processing, testing and burial. The first part of this essay examines the cultural phenomenon of "danger consumption" embodied in atomic museums and landmarks across the United KEY WORDS States. The second part reviews the role of artists and designers in this paradoxical Nuclear culture undertaking, particularly designers who mark the danger sites, making them Nuclear landscape publicly safe and accessible, or who fashion 'atomic monuments'. The role of Post-nuclear monuments design and art is further examined using the submissions to the 2001 Bulletin of Atomic museums Atomic Scientists Plutonium Memorial Contest, which highlights a range of Post-nuclear gardens/wilderness design approaches to creating a memorial to the world's storage of the lasting, Nuclear waste glowing poison. -

Table of Contents Instructor Information Course Materials

STUDENT WARNING: This course syllabus is from a previous semester archive and serves only as a preparatory reference. Please use this syllabus as a reference only until the professor opens the classroom and you have access to the updated course syllabus. Please do NOT purchase any books or start any work based on this syllabus; this syllabus may NOT be the one that your individual instructor uses for a course that has not yet started. If you need to verify course textbooks, please refer to the online course description through your student portal. This syllabus is proprietary material of APUS. School of Arts & Humanities MILH699 Master of Arts in History - Thesis Credit Hours: 3 Length of Course: 16 Weeks Prerequisite: HIST691 Table of Contents Instructor Information Course Materials Course Description Evaluation Procedures Course Scope Course Outline Course Objectives Online Research Services Course Delivery Method Selected Bibliography Instructor Information Table of Contents Course Description Preparation for the Master of Arts in Military History Capstone (Thesis) seminar begins on day one of a student's graduate program of study. The theories, research methods and analytical skills, and substantive knowledge obtained through their master's curriculum provide the basis for the thesis project. Students are required to develop primary and secondary source materials on their research topic and address the writing requirements as described in the syllabus and classroom assignments. The thesis proposal must provide a clear description of a question or problem and a proposed method of answering the question or solving the problem. Guidance on the format of the research proposal and a sample proposal are contained in the APUS Thesis Manual. -

Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1959-1989 Michael A

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2016 Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989 Michael A. St. Jacques James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation St. Jacques, Michael A., "Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989" (2016). Masters Theses. 102. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/102 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Their Swords, Our Plowshares: "Peaceful" Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1949-1989 Michael St. Jacques A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2016 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Maria Galmarini Dr. Alison Sandman Dedication For my wife, my children, my siblings, and all of my family and friends who were so supportive of me continuing my education. At the times when I doubted myself, they never did. -

Foia/Pa-2011-0118/Foia/Pa-2011

From: Bulletin News To: NRC-editors(bbulletinnews.com Subject: NRC News Summary for Monday, April 04, 2011 Date: Monday, April 04, 2011 7:08:53 AM Attachments: NRCSummarv110404.doc NRCSummarv110404.odf NRCCliis110404,doc NRCClips11O404,pdf This morning's Nuclear Regulatory Commission News Summary and Clips are attached. Website: You can also read today's briefing, including searchable archive of past editions, at http://www.BulletinNews.com/nrc. Full-text Links: Clicking the hypertext links in our write-ups will take you to the newspapers' original full-text articles. Interactive Table of Contents: Clicking a page number on the table of contents page will take you directly to that story. Contractual Obligations and Copyright: This copyrighted material is for the internal use of Nuclear Regulatory Commission employees only and, by contract, may not be redistributed without BulletinNews' express written consent. Contact Information: Please contact us any time at 703-483-6100 or NRC [email protected]. Use of this email address will automatically result in your message being delivered to everyone involved with your service, including senior management. Thank you. A4g NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION NEws SUMMARY MONDAY, APRIL 4,2011 7:00 AM EDT W .BULLETINNEWS.COM/NRC TODAY'S EDITION I NRC News: PPL Will Learn Lessons From Japan As It Seeks NRC Approval NRC To Conduct Seismic Review At All US Reactor Sites .......... 1 For New Plant .............................................................. 9 Jaczko's Comment On Spent Fuel Storage Faulted ................ 2 GE CEO Offers Assistance To TEPCO .................................. 9 NRC Lists Recent Violations At Fort Calhoun Plant ................ 2 Panelists Say Nuclear Industry Freeze Unlikely, Say Industry Wolf Creek Says Problem Areas Returned To Normal ........... -

Dissertation Greece: Tourism Performance During the Financial Crisis (2009 – 2017)

Hellenic Open University Master in Business Administration (MBA) Dissertation Greece: Tourism performance during the financial crisis (2009 – 2017) Bournazou Eleni Supervisor: Persefoni Polychronidou Patras, Greece, July 2018 Theses / Dissertations remain the intellectual property of students (“authors/creators”), but in the context of open access policy they grant to the HOU a non-exclusive license to use the right of reproduction, customisation, public lending, presentation to an audience and digital dissemination thereof internationally, in electronic form and by any means for teaching and research purposes, for no fee and throughout the duration of intellectual property rights. Free access to the full text for studying and reading does not in any way mean that the author/creator shall allocate his/her intellectual property rights, nor shall he/she allow the reproduction, republication, copy, storage, sale, commercial use, transmission, distribution, publication, execution, downloading, uploading, translating, modifying in any way, of any part or summary of the dissertation, without the explicit prior written consent of the author/creator. Creators retain all their moral and property rights. 1 Greece: Tourism performance during the financial crisis (2009 – 2017) Eleni Bournazou Supervising Committee Supervisor: Co-Supervisor: Persefoni Polychronidou Maria Mavri Assistant Professor at Technological Assistant Professor of Quantitative Educational Institute of Central Methods at Department of Business Macedonia Administration of the University of the Aegean 2 “Eleni Bournazou”, “Greece: Tourism performance during the financial crisis (2009-2017)” Acknowledgments After an intensive period of working in the mornings and writing till late in the night for my thesis, I would like to reflect on the people who have supported and helped me so much throughout the last months. -

Tourism Introduction • 1

TOURISM INTRODUCTION • 1. TOURIST – Is a temporary visitor staying for a period of at least 24 hours in the country visited and the purpose of whose journey can be classified under one of the following heads: • a) Leisure (recreation, holiday, health, study, religion and sport) b) Business, family, mission, meeting. – As per the WTO’s definition following persons are to be regarded as tourists: – i) Persons travelling for pleasure, for domestic reasons, for health etc. – ii) Persons travelling for meetings or in representative capacity of any kind (scientific, administrative, religious etc.) – iii) Persons travelling for business purposes. – iv) Persons arriving in the course of sea cruises, even when they stay for less than 24 hours (in respect of this category of persons the condition of usual place of residence is waived off. 2 • 2. EXCURSIONIST—is a temporary visitor staying for a period of less than 24hours in the country visited. (Including travellers on the cruises). • 3. TRAVELER or TRAVELLER - commonly refers to one who travels, especially to distant lands. 3 Visitor • As per WTO is that it does not talk about the Visits made within the country. • For these purposes a distinction is drawn between a Domestic and an International Visitor. • Domestic Visitor-A person who travels within the country he is residing in, outside the place of his usual environment for a period not exceeding 12 months. • International Visitor –A person who travels to a country other than the one in which he has his usual residence for a period not exceeding