Post-Nuclear Monuments, Museums, and Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Nuclear Issues Through Popular Culture Texts

Social Education 82(3), pp. 149–150, 151–154 ©2018 National Council for the Social Studies The Bomb and Beyond: Teaching Nuclear Issues through Popular Culture Texts Hiroshi Kitamura and Jeremy Stoddard America’s atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—on August 6 and 9, 1945, of ways, but often revolves around an respectively—instantly killed some 200,000 Japanese and precipitated the end of effort to understand how and why the World War II. They also helped usher in the Cold War, a new era of global tension Truman administration unleashed a that pushed the world towards the brink of destruction. In this menacing climate, in pair of destructive weapons on a mass which the United States and the then-Soviet Union pursued a fierce international of civilians. Often a debate or delibera- rivalry, nuclear issues became central to top-level diplomacy and policymaking. tion model is used to engage students in Citizens around the world experienced a full spectrum of emotions—fear, paranoia, exploring the motives and implications rage, and hope—as they lived in this “nuclear world.” of official U.S. decision making—such as to save American lives, check Soviet Presently, nearly three decades after classroom, including films, TV shows, expansionism, or justify the two-billion- the fall of the Berlin Wall, the original video games, photography, and online dollar cost of the Manhattan Project. But nuclear arms race has subsided, but databases. These cultural texts illustrate this intellectual exercise also carries the nuclear issues remain seminal. Continued diverse societal views from different risk of reducing the experience to strate- challenges related to the development points in time. -

Concept and Types of Tourism

m Tourism: Concept and Types of Tourism m m 1.1 CONCEPT OF TOURISM Tourism is an ever-expanding service industry with vast growth potential and has therefore become one of the crucial concerns of the not only nations but also of the international community as a whole. Infact, it has come up as a decisive link in gearing up the pace of the socio-economic development world over. It is believed that the word tour in the context of tourism became established in the English language by the eighteen century. On the other hand, according to oxford dictionary, the word tourism first came to light in the English in the nineteen century (1811) from a Greek word 'tomus' meaning a round shaped tool.' Tourism as a phenomenon means the movement of people (both within and across the national borders).Tourism means different things to different people because it is an abstraction of a wide range of consumption activities which demand products and services from a wide range of industries in the economy. In 1905, E. Freuler defined tourism in the modem sense of the world "as a phenomena of modem times based on the increased need for recuperation and change of air, the awakened, and cultivated appreciation of scenic beauty, the pleasure in. and the enjoyment of nature and in particularly brought about by the increasing mingling of various nations and classes of human society, as a result of the development of commerce, industry and trade, and the perfection of the means of transport'.^ Professor Huziker and Krapf of the. -

Transcript by Rev.Com Had Seating for 100 People, and Would Have Been the Emergency Senate Chamber

Joanne Freeman: Major funding for Back Story is provided by an anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Virginia, and the Robert and Joseph Cornel Memorial Foundation. Ed Ayers: From Virginia Humanities, this is Back Story. Brian Balogh: Welcome to Back Story, the show that explains the history behind today's headlines. I'm Brian Balogh. Ed Ayers: I'm Ed Ayers. Joanne Freeman: I'm Joanne Freeman. Ed Ayers: If you're new to the podcast, we're all historians. Each week, we explore the history of one topic that's been in the news. Joanne Freeman: Now, picture a luxury hotel. Attentive staff buzz around serving drinks to thirsty golfers who've just come in after playing 18 holes; but behind a false wall, there's a blast door intended to keep out radiation from a nuclear bomb. Nobody who works here knows, but this is where the American president, senators, and congressmen will hide out if America comes under attack by nuclear weapons. Sounds like a James Bond movie, right? Joanne Freeman: We're going to start off today by going underground to a secret facility standing by not far from here. Garrett Graff: ... I ever went to was the Greenbrier bunker, which would have been the congressional bunker and relocation facility during the course of the Cold War. Brian Balogh: This is the writer and historian, Garrett Graff. Garrett Graff: It was this bunker hidden under this very fine golf resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. The resort is still used as a annual congressional retreat. -

Commodification of Cultural Identities And/Or Empowerment of Local Communities: Developing a Route of Nuclear Tourism

SOCIETY. INTEGRATION. EDUCATION Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Volume V, May 25th-26th, 2018. 145-158 COMMODIFICATION OF CULTURAL IDENTITIES AND/OR EMPOWERMENT OF LOCAL COMMUNITIES: DEVELOPING A ROUTE OF NUCLEAR TOURISM Natalija Mažeikienė Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania Eglė Gerulaitienė Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania Šiauliai University, Lithuania Abstract. Research presented in the paper focuses on commodification of cultural identities and community empowerment strategies of cultural tourism in Visaginas. One of challenges in developing tourism is orientation toward profit and commodification of culture, which becomes a problem in regard to practicing authentic identities. The article presents efforts of researchers working in the project EDUATOM to scientifically substantiate construction of new educational nuclear/ atomic tourism route in the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant (INPP) region. The authors discuss what diverse parameters and elements of place identity could be included and represented in the tourism in Visaginas and how community empowerment and involvement of different stakeholders might contribute to practicing various commodification strategies. The article analyses commodification of cultural identities and community empowerment strategies of educational, cultural, nuclear/atomic tourism in Visaginas, using research strategy of case study, including methods of document analysis, conversations (formal and informal) with stakeholders, secondary data analysis, construction of Post-Soviet -

Join Vivian on the Road

10/2017 John Grisham on North Carolina Bookwatch • Rootle’ween • Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Join Vivian on the Road his season, hit the road for some tasty Tadventures with James Beard Award- winning Chef Vivian Howard (and her food truck) as she supports her first cookbook, a 500-page, New York Times bestselling “culinary love letter.” Don’t miss a morsel of A Chef’s Life’s fifth season—new episodes premiere Thursday nights, at 9:30, on UNC-TV, Public Media North Carolina. Photos: Josh Woll aboutUNC-TV CenterPiece is the monthly program guide of UNC-TV, North Carolina’s public media network and broadcast service licensed to the University UNC-TV’s Exciting Fall Line Up! of North Carolina. Contributions are tax deduct- ible to the extent permitted by law. UNC-TV’s central offices and studios are housed in the Make no mistake about it—the key to new programs on Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Communications UNC-TV is you. We know you share our uncompromising Center in Research Triangle Park. standards and value the opportunity to provide the funds that make our public media service second to none. 10 TW Alexander Drive PO Box 14900 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-4900 So when you see this envelope in your mailbox, please 1-919-549-7000 or 1-800-906-5050 send your special donation to UNC-TV today and keep UNC-TV network stations are: more great programs coming your way. Contribute Asheville WUNF-TV securely online at unctv.org/programs. Canton/Waynesville WUNW-TV Chapel Hill/Raleigh/Durham WUNC-TV Charlotte/Concord WUNG-TV Thank you for -

Table of Contents Instructor Information Course Materials

STUDENT WARNING: This course syllabus is from a previous semester archive and serves only as a preparatory reference. Please use this syllabus as a reference only until the professor opens the classroom and you have access to the updated course syllabus. Please do NOT purchase any books or start any work based on this syllabus; this syllabus may NOT be the one that your individual instructor uses for a course that has not yet started. If you need to verify course textbooks, please refer to the online course description through your student portal. This syllabus is proprietary material of APUS. School of Arts & Humanities MILH699 Master of Arts in History - Thesis Credit Hours: 3 Length of Course: 16 Weeks Prerequisite: HIST691 Table of Contents Instructor Information Course Materials Course Description Evaluation Procedures Course Scope Course Outline Course Objectives Online Research Services Course Delivery Method Selected Bibliography Instructor Information Table of Contents Course Description Preparation for the Master of Arts in Military History Capstone (Thesis) seminar begins on day one of a student's graduate program of study. The theories, research methods and analytical skills, and substantive knowledge obtained through their master's curriculum provide the basis for the thesis project. Students are required to develop primary and secondary source materials on their research topic and address the writing requirements as described in the syllabus and classroom assignments. The thesis proposal must provide a clear description of a question or problem and a proposed method of answering the question or solving the problem. Guidance on the format of the research proposal and a sample proposal are contained in the APUS Thesis Manual. -

The Historical Film As Real History ROBERT A. ROSENSTONE

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert The Historical Film as Real History ROBERT A. ROSENSTONE Let's face the facts and admit it: historical films trouble and disturb (most) professional historians. Why? We all know the obvious answers. Because, historians will say, films are inaccurate. They distort the past. They fictionalize, trivialize, and romanticize important people, events, and movements. They falsify History. As a subtext to these overt answers, we can hear some different, unspoken answers: Film is out of the control of historians. Film shows that academics do not own the past. Film creates a historical world with which the written word cannot compete, at least for popularity .Film is a disturbing symbol of an increasingly postliterate world (in which people can read but won't). Let me add an impolite question: How many professional historians, when it comes to fields outside their areas of expertise, learn about the past from film? How many Americanists, for example, know the great Indian leader primarily from Gandhi ? Or how many Europeanists the American Civil War from Glory , or Gone with the Wind ? Or how many Asianists early modern France from The Return of Martin Guerre ? My point: the historical film has been making its impact upon us (and by «us» I mean the most serious of professional historians) for many years now, and its time that we began to take it seriously. By this I mean we must begin to look at film, on its own terms, as a way of exploring the way the past means to us today. -

Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1959-1989 Michael A

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2016 Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989 Michael A. St. Jacques James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation St. Jacques, Michael A., "Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989" (2016). Masters Theses. 102. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/102 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Their Swords, Our Plowshares: "Peaceful" Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1949-1989 Michael St. Jacques A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2016 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Maria Galmarini Dr. Alison Sandman Dedication For my wife, my children, my siblings, and all of my family and friends who were so supportive of me continuing my education. At the times when I doubted myself, they never did. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. COLLISIONS OF HISTORY AND LANGUAGE: NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTING, HUMAN ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS ABUSES, AND COVER-UP IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS by Holly M. -

Foia/Pa-2011-0118/Foia/Pa-2011

From: Bulletin News To: NRC-editors(bbulletinnews.com Subject: NRC News Summary for Monday, April 04, 2011 Date: Monday, April 04, 2011 7:08:53 AM Attachments: NRCSummarv110404.doc NRCSummarv110404.odf NRCCliis110404,doc NRCClips11O404,pdf This morning's Nuclear Regulatory Commission News Summary and Clips are attached. Website: You can also read today's briefing, including searchable archive of past editions, at http://www.BulletinNews.com/nrc. Full-text Links: Clicking the hypertext links in our write-ups will take you to the newspapers' original full-text articles. Interactive Table of Contents: Clicking a page number on the table of contents page will take you directly to that story. Contractual Obligations and Copyright: This copyrighted material is for the internal use of Nuclear Regulatory Commission employees only and, by contract, may not be redistributed without BulletinNews' express written consent. Contact Information: Please contact us any time at 703-483-6100 or NRC [email protected]. Use of this email address will automatically result in your message being delivered to everyone involved with your service, including senior management. Thank you. A4g NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION NEws SUMMARY MONDAY, APRIL 4,2011 7:00 AM EDT W .BULLETINNEWS.COM/NRC TODAY'S EDITION I NRC News: PPL Will Learn Lessons From Japan As It Seeks NRC Approval NRC To Conduct Seismic Review At All US Reactor Sites .......... 1 For New Plant .............................................................. 9 Jaczko's Comment On Spent Fuel Storage Faulted ................ 2 GE CEO Offers Assistance To TEPCO .................................. 9 NRC Lists Recent Violations At Fort Calhoun Plant ................ 2 Panelists Say Nuclear Industry Freeze Unlikely, Say Industry Wolf Creek Says Problem Areas Returned To Normal ........... -

The Historical Film : Ten Words Cannot

51 Robert A. Rosenstone Looking tit the Past in a Postliterate Age Dislike (or fear) of the visual media has not prevented historians from becom- ing increasingly involved with film in recent years: film has invaded the class- room, though it is difficult to specify if this is due to the "laziness" of teachers, the postliteracy of students, or the realization that film can do something writ- The Historical Film : ten words cannot . Scores, perhaps hundreds, of historians have become periph- erally involved in the Looking process of making films : some as advisers on film projects, at the Past in a dramatic and documentary, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities (which requires that filmmakers create panels of advisers but-to Postliterate Age disappoint Gottschalk-makes no provision that the advice actually be taken); others as talking heads in historical documentaries . Sessions on history and film have become a routine part of academic conferences, as well as annual conven- tions ofmajor professional groups like the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association . Reviews of historical films have become features of such academic journals as the American Historical Review, Historians and Film Journal of American History, Radical History Review, Middle Eastern Studies Association Bulletin, and Latin American Research Review. Let's be blunt and admit it: historical films trouble All this activity and disturb professional his- has hardly led to a consensus on how to evaluate the con- torians-have -

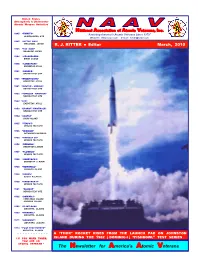

Mar 2010 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor March, 2010 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA ------------ A “THOR” ROCKET RISES FROM THE LAUNCH PAD ON JOHNSTON “ IF YOU WERE THERE, ISLAND DURING THE 1962 ( DOMINIC-I ) “FISHBOWL” TEST SERIES YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDERS COMMENTS efforts. It is important to note that the Directors and Officers of NAAV dedicate their service to our Mission Statement without NAAV is now entering it’s 31st. year of assist- compensation. Our sole source of operating income is derived ing America’s Atomic-Veteran community in from annual membership dues and ( tax exempt ) contribu- the areas of obtaining proper documentation tions.