Poetics and Politics: Bikini Atoll and World Heritage Listing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Nuclear Issues Through Popular Culture Texts

Social Education 82(3), pp. 149–150, 151–154 ©2018 National Council for the Social Studies The Bomb and Beyond: Teaching Nuclear Issues through Popular Culture Texts Hiroshi Kitamura and Jeremy Stoddard America’s atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—on August 6 and 9, 1945, of ways, but often revolves around an respectively—instantly killed some 200,000 Japanese and precipitated the end of effort to understand how and why the World War II. They also helped usher in the Cold War, a new era of global tension Truman administration unleashed a that pushed the world towards the brink of destruction. In this menacing climate, in pair of destructive weapons on a mass which the United States and the then-Soviet Union pursued a fierce international of civilians. Often a debate or delibera- rivalry, nuclear issues became central to top-level diplomacy and policymaking. tion model is used to engage students in Citizens around the world experienced a full spectrum of emotions—fear, paranoia, exploring the motives and implications rage, and hope—as they lived in this “nuclear world.” of official U.S. decision making—such as to save American lives, check Soviet Presently, nearly three decades after classroom, including films, TV shows, expansionism, or justify the two-billion- the fall of the Berlin Wall, the original video games, photography, and online dollar cost of the Manhattan Project. But nuclear arms race has subsided, but databases. These cultural texts illustrate this intellectual exercise also carries the nuclear issues remain seminal. Continued diverse societal views from different risk of reducing the experience to strate- challenges related to the development points in time. -

Post-Nuclear Monuments, Museums, and Gardens

Post~nuclear Monuments, Museums, and Gardens * MIRA ENGLER INTRODUCTION Mira Engler, Associate Professor of Lanrucape Architecture at Iowa ARKED BY THE SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY of atomic energy, the nuclear age, which State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, spans the twentieth century, has changed the nature of culture as well as M United States of America. l the landscape. Vast, secret landscapes play host to nuclear arms and commercial Email: [email protected] energy producers.2 Nuclear sites concern not only scientists and politicians, but also environmental designers/artists. The need to evoke a cultural discourse, protect future generations, reveal or conceal radioactive burial sites and recycle retired installations engenders our participation. How do we intersect with these hellish places? Do we have a potent role in addressing this conundrum? In what follows, I confront the consumption and design of today's most daunting places - the landscapes of nuclear material production, processing, testing and burial. The first part of this essay examines the cultural phenomenon of "danger consumption" embodied in atomic museums and landmarks across the United KEY WORDS States. The second part reviews the role of artists and designers in this paradoxical Nuclear culture undertaking, particularly designers who mark the danger sites, making them Nuclear landscape publicly safe and accessible, or who fashion 'atomic monuments'. The role of Post-nuclear monuments design and art is further examined using the submissions to the 2001 Bulletin of Atomic museums Atomic Scientists Plutonium Memorial Contest, which highlights a range of Post-nuclear gardens/wilderness design approaches to creating a memorial to the world's storage of the lasting, Nuclear waste glowing poison. -

The Historical Film As Real History ROBERT A. ROSENSTONE

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert The Historical Film as Real History ROBERT A. ROSENSTONE Let's face the facts and admit it: historical films trouble and disturb (most) professional historians. Why? We all know the obvious answers. Because, historians will say, films are inaccurate. They distort the past. They fictionalize, trivialize, and romanticize important people, events, and movements. They falsify History. As a subtext to these overt answers, we can hear some different, unspoken answers: Film is out of the control of historians. Film shows that academics do not own the past. Film creates a historical world with which the written word cannot compete, at least for popularity .Film is a disturbing symbol of an increasingly postliterate world (in which people can read but won't). Let me add an impolite question: How many professional historians, when it comes to fields outside their areas of expertise, learn about the past from film? How many Americanists, for example, know the great Indian leader primarily from Gandhi ? Or how many Europeanists the American Civil War from Glory , or Gone with the Wind ? Or how many Asianists early modern France from The Return of Martin Guerre ? My point: the historical film has been making its impact upon us (and by «us» I mean the most serious of professional historians) for many years now, and its time that we began to take it seriously. By this I mean we must begin to look at film, on its own terms, as a way of exploring the way the past means to us today. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. COLLISIONS OF HISTORY AND LANGUAGE: NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTING, HUMAN ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS ABUSES, AND COVER-UP IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS by Holly M. -

The Historical Film : Ten Words Cannot

51 Robert A. Rosenstone Looking tit the Past in a Postliterate Age Dislike (or fear) of the visual media has not prevented historians from becom- ing increasingly involved with film in recent years: film has invaded the class- room, though it is difficult to specify if this is due to the "laziness" of teachers, the postliteracy of students, or the realization that film can do something writ- The Historical Film : ten words cannot . Scores, perhaps hundreds, of historians have become periph- erally involved in the Looking process of making films : some as advisers on film projects, at the Past in a dramatic and documentary, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities (which requires that filmmakers create panels of advisers but-to Postliterate Age disappoint Gottschalk-makes no provision that the advice actually be taken); others as talking heads in historical documentaries . Sessions on history and film have become a routine part of academic conferences, as well as annual conven- tions ofmajor professional groups like the Organization of American Historians and the American Historical Association . Reviews of historical films have become features of such academic journals as the American Historical Review, Historians and Film Journal of American History, Radical History Review, Middle Eastern Studies Association Bulletin, and Latin American Research Review. Let's be blunt and admit it: historical films trouble All this activity and disturb professional his- has hardly led to a consensus on how to evaluate the con- torians-have -

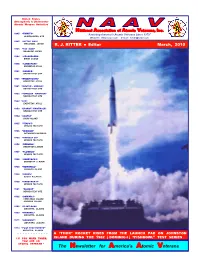

Mar 2010 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor March, 2010 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA ------------ A “THOR” ROCKET RISES FROM THE LAUNCH PAD ON JOHNSTON “ IF YOU WERE THERE, ISLAND DURING THE 1962 ( DOMINIC-I ) “FISHBOWL” TEST SERIES YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDERS COMMENTS efforts. It is important to note that the Directors and Officers of NAAV dedicate their service to our Mission Statement without NAAV is now entering it’s 31st. year of assist- compensation. Our sole source of operating income is derived ing America’s Atomic-Veteran community in from annual membership dues and ( tax exempt ) contribu- the areas of obtaining proper documentation tions. -

CSIF/Calgary Public Library 16Mm and Super 8 Film Collection

CSIF Film Library CSIF/Calgary Public Library 16mm and Super 8 Film Collection Film Running Time Number Title Producer Date Description (min) A long, hard look at marriage and motherhood as expressed in the views of a group of young girls and married women. Their opinions cover a wide range. At regular intervals glossy advertisements extolling romance, weddings, babies, flash across the screen, in strong contrast to the words that are being spoken. The film ends on a sobering thought: the solution to dashed expectations could be as simple as growing up before marriage. Made as part of the Challenge for Change 1 ... And They Lived Happily Ever After Len Chatwin, Kathleen Shannon 1975 program. 13 min Presents an excerpt from the original 1934 motion picture. A story of bedroom confusions and misunderstandings that result when an American dancer begins pursuing and English woman who, in turn, is trying to invent the technical grounds of 2 Gay Divorcee, The (excerpt) Films Incorporated 1974 divorce 14 A hilarious parody of "Star Wars". Uses a combination of Ernie Fosselius and Michael Wiese special effects and everyday household appliances to simulate 4 Hardware Wars (Pyramid Films) 1978 sophisticated space hardware. 10 Laurel and Hardy prepare for a Sunday outing with their wives 5 Perfect Day, A Hal Roach Studios (Blackhawk Films) 1929 and Uncle Edgar Kennedy, who has a gouty foot. 21 Witty, sad, and often bizarre anecdotes of Chuck Clayton, the 73-year-old former manager of the largest cemetery east of 6 Boo Hoo National Film Board of Canada 1975 Montreal, told as he wanders nostalgically through its grounds. -

In the Shadow of the Moon 2007 PG 109 Minutes David Sington And

In the Shadow of the Moon 2007 PG 109 minutes David Sington and Christopher Riley's acclaimed documentary reveals the history of the Apollo space program through interviews with the brave astronauts who lived through a paradigm-shifting chapter in world history. Devoted to President John F. Kennedy's goal of sending a man to the moon, the NASA project pushed the envelope of what was humanly possible. But the program also experienced several failures, one of which resulted in tragedy. Man on Wire 2008 PG-13 94 minutes Philippe Petit captured the world's attention in 1974 when he successfully walked across a high wire between New York's Twin Towers. This Oscar winner for Best Documentary explores the preparations that went into the stunt as well as the event and its aftermath. Obsessed with the towers even before they were fully constructed, Petit sneaked into the buildings several times to determine the equipment he needed to accomplish his daring feat. American Experience: Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple 2006 NR 86 minutes How could one man -- Peoples Temple leader Jim Jones -- persuade 900 people to commit mass suicide by drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid in the jungles of Guyana? This penetrating portrait of the demented preacher attempts to answer that question. Using never- before-seen footage and audio accounts of two Jonestown survivors, documentarian Stanley Nelson paints a chilling picture of a social experiment gone horribly awry. When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts 2006 TV-MA 3 discs Spike Lee commemorates the people of New Orleans with a four-hour epic documentary that not only recounts the events of late August 2005 but asks why they unfolded the way they did in the first place. -

GORSKI-THESIS.Pdf (2.396Mb)

Copyright by Susanna Brooks Gorski 2010 The Thesis Committee for Susanna Brooks Gorski Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Artist, the Atom, and the Bikini Atoll: Ralston Crawford Paints Operation Crossroads APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson John R. Clarke The Artist, the Atom, and the Bikini Atoll: Ralston Crawford Paints Operation Crossroads by Susanna Brooks Gorski, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2010 Abstract The Artist, the Atom, and the Bikini Atoll: Ralston Crawford Paints Operation Crossroads Susanna Brooks Gorski, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson This thesis explores Ralston Crawford‘s canvases painted after witnessing the events of Operation Crossroads at the Bikini Atoll in 1946. Commissioned by Fortune, the artist provides the viewer with a unique and captivating view of the destruction wrought by atomic weaponry. Through a careful look at Crawford‘s relationship with Fortune, Edith Halpert‘s Downtown Gallery, and Crawford‘s artistic contemporaries, this thesis positions the paintings within the art historical and cultural context of the mid- twentieth century and asserts their importance to the history of the Atomic Age. The thesis traces Crawford‘s artistic development and his use of an Americanized Cubist language. In addition, the thesis looks closely at the rich cultural fabric of the postwar era and evaluates Crawford‘s position in the American Art scene. -

Revolutionary Era Unit 3: New Nation Unit 4: Expansion, Reform

Unit 1: Colonization Unit 10: Cold War Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner) Post-WWII Economy & Society 1492: Conquest of Paradise Salesman Apocalypto Death of a Salesman The New World A Beautiful Mind The Mission Awakenings Black Robe Good Night & Good Luck God in America: Episode 1 - The New Adam The Majestic We Shall Remain: Episode 1 - After the Mayflower Citizen Cohn Africans in America: The Terrible Transformation* Point of Order America: The Story of Us - Rebels* The Good Shepherd The Scarlet Letter Atomic Cafe The Crucible* Radio Bikini The Salem Witch Trials* Chosin The Last of the Mohicans* American Experience: The Lobotomist Unit 2: Revolutionary Era American Experience: The Polio Crusade Pleasantville Benjamin Franklin: Citizen of the World* American Experience: Tupperware! The Declaration of Independence* Julie & Julia Founding Brothers* 1776 Space Race & Cold War Technology The Crossing* October Sky The Patriot* The Right Stuff American Experience: War Letters From the Earth to the Moon American Experience: Into the Deep - America, Whaling & the When We Left Earth World Apollo 13 America: The Story of Us - Revolution* American Experience: The Living Weapon Africans in America: Revolution* Saving the National Treasures* Capote National Treasure Dr. Strangelove Unit 3: New Nation J. Edgar John Adams* Hoffa Ken Burns: Thomas Jefferson* Thirteen Days Sally Hemings: An American Scandal JFK Jefferson in Paris The Kennedys Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery* Bobby Sacagawea American Experience: The Kennedys We Shall Remain: -

For Additions to This Section Please See the Media Resources Desk. for Availability Check the Library Catalog

UNLV LIBRARY Abraham Lincoln: In His Own Words. MEDIA RESOURCES CATALOG Teaching Co. (1999) HISTORY Presents an analysis of the speeches Summer 2011 of Abraham Lincoln. pt. 1. A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs & Freedom. lecture 1. Lincoln and rhetoric California Newsreel (1996) lecture 2. The Lyceum speech, 1838 Biography of African-American labor lecture 3. The temperance speech, leader, journalist, and civil rights activist, A. 1842 Philip Randolph. lecture 4. Lincoln as a young Whig Video Cassette (1 hr. 27 min.) lecture 5. Lincoln returns to politics E 185.97 R27 A62 lecture 6. The Peoria speech, 1854 lecture 7. Lincoln's rhetoric and Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House politics, 1854-1857 Divided. lecture 8. The Springfield speech, WGBH Educational Foundation (2001) 1857 A six-part program which examines lecture 9. The House divided speech, the Lincolns' family life and marriage, 1858 Abraham Lincoln's presidency, and the Civil lecture 10. The Chicago speech, July War era. 1858 disc 1. Ambition ; We are elected lecture 11. The Springfield speech, disc 2. Shattered ; Dearest of all July 1858 things lecture 12. The debate about the disc 3. This frightful war ; Blind with debates weeping pt. 2. 3 videodiscs (360 min.) lecture 13. The Lincoln-Douglas E457.25 .A37 2001 discs 1-3 debates I lecture 14. The Lincoln-Douglas Abraham Lincoln: A New Birth of debates II Freedom. lecture 15. The Lincoln-Douglas Quest Productions (1993) debates III Describes Abraham Lincoln as a lecture 16. The aftermath of the person and tells of his responsibility in debates bringing an end to slavery in the U.S. -

1985 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1985 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL Now under the administration of Sundance Institute, The United States Film Festival presented over 80 feature- length fi lms this year, including: STRANGER THAN PARADISE, THE FALCON AND THE SNOWMAN, MRS. SOFFEL, BEFORE STONEWALL: THE MAKING OF A GAY AND LESBIAN COMMUNITY, THE KILLING FLOOR, BLOOD SIMPLE, THE TIMES OF HARVEY MILK, BROTHER FROM ANOTHER PLANET, THE KILLING FIELDS, and WHERE THE GREEN ANTS DREAM. The Festival also spotlighted the work of Christopher Petit (AN UNSUITABLE JOB FOR A WOMAN, FLIGHT TO BERLIN), Francois Truffaut (THE 400 BLOWS, DAY FOR NIGHT), Ivan Passer (INTIMATE LIGHTING, CUTTER’S WAY) and the students of Roger Corman. There was an emphasis on international fi lm, with screenings of seven new Australian works alone. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE Documentary—SEVENTEEN, directed by Joel DeMott and Jeff Kreines Dramatic—BLOOD SIMPLE, directed by Joel Coen SPECIAL JURY PRIZES Documentary—AMERICA AND LEWIS HINE, directed by Nina Rosenblum; THE TIMES OF HARVEY MILK, directed by Rob Epstein; STREETWISE, directed by Martin Bell; KADDISH, directed by Steve Brand; and IN HEAVEN THERE IS NO BEER, directed by Les Blank Dramatic—THE KILLING FLOOR, directed by William Duke; ALMOST YOU, directed by Adam Brooks; and STRANGER THAN PARADISE, directed by Jim Jarmusch. USFF Staff Group Photo. PHOTO BY SANDRIA MILLER JURORS [Documentary Competition] Frederick Wiseman, D.A. Pennebaker, Barbara Kopple [Dramatic Competition] Robert M. Young, Peter Biskind, Mirra Bank 1985 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL FILMS 400 Blows,