Redalyc.Maria Helena Mendes Pinto and the Encounter with Japan: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ceramics in Portuguese Architecture (16Th-20Th Centuries)

CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) CERAMICS IN PORTUGUESE ARCHITECTURE (16TH-20TH CENTURIES) A. M. Portela, F. Queiroz Art Historians - Portugal [email protected] ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to present a synoptic view of the evolution of Portuguese architectural ceramics, particularly focusing on the 19th and 20th centuries, because the origins of current uses of ceramic tiles in Portuguese architecture stem from those periods. Thus, the paper begins with the background to the use of ceramics in Portuguese architecture, between the 16th and 18th centuries, through some duly illustrated paradigmatic examples. The study then presents examples of the 19th century, in a period of transition between art and industry, demonstrating the diversity and excellence of Portuguese production, as well as the identifying character of the phenomenon of façade tiling in the Portuguese urban image. The study concludes with a section on the causes of the decline in the use of ceramic materials in Portuguese architecture in the first decades of the 20th century, and the appropriation of ceramic tiling by the popular classes in their vernacular architecture. Parallel to this, the paper shows how the most erudite route for ceramic tilings lay in author works, often in public buildings and at the service of the nationalistic propaganda of the dictatorial regime. This section also explains how an industrial upgrading occurred that led to the closing of many of the most important Portuguese industrial units of ceramic products for architecture, foreshadowing the current ceramic tiling scenario in Portugal. 1 CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) 1. INTRODUCTION In Portugal, ornamental ceramics used in architecture are generally - and almost automatically - associated only with tiles, even though, depending on the historical period, one can enlarge considerably the approach, beyond this specific form of ceramic art. -

Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, a Portuguese Art Nouveau Artist Rita Nobre Peralta, Leonor Da Costa Pereira Loureiro, Alice Nogueira Alves

Strand 2. Art Nouveau and Politics in the Dawn of Globalisation Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, a portuguese Art Nouveau artist Rita Nobre Peralta, Leonor da Costa Pereira Loureiro, Alice Nogueira Alves Abstract The Art Nouveau gradual appearance in the Portuguese context it’s marked by the multidimensional artist Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, and by his audacious affirmation as an avant- garde figure focused upon the industrial modernity, that is able to highlight some of the most original artistic solutions of his time. He manages to include in his production a touch of Portuguese Identity alongside with the new European trends of the late 19th century, combining traditional production techniques, themes and typologies, which are extended to artistic areas as varied as the press, the decorative arts and the decoration of cultural events. In this article, we pretend to analyse some of his proposals within Lisbon's civil architecture interior design and his participation in the Columbian Exhibition, held in Madrid in 1892, where he was a member of the Portuguese Legation, co-responsible for the selection and composition of the exhibition contents. Keywords: Art Nouveau, Cultural heritage, Portuguese identity, 19 th Century, interior and exterior design, Decorative arts, ceramics, tiles, furniture, Colombian Exposition of Madrid 1892 1 THE FIRST YEARS - PRESS, HUMOR AND AVANT-GARDE Rafael Augusto Prostes Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905) was born on March 21, 1846, in Lisbon, Portugal. His taste for art has always been boosted up by his father, Manuel Maria Bordalo Pinheiro who, together with his occupation as a civil servant, was also known as a painter and an external student of the Academy of Fine Arts of Lisbon. -

Booklet of Information

1 ESMC2009 7th EUROMECH Solid Mechanics Conference Instituto Superior Técnico Lisbon, Portugal. September 7-11, 2009 PROGRAMME Lisbon 2009 2 3 Welcome On behalf of European Mechanics Society (EUROMECH) we are pleased to welcome you to Lisbon for the 7th EUROMECH Solid Mechanics Conference held at Instituto Superior Técnico of the Technical University of Lisbon. EUROMECH has the objective to engage in all activities intended to promote in Europe the development of mechanics as a branch of science and engineering. Activities within the field of mechanics range from fundamental research to applied research in engineering. The approaches used comprise theoretical, analytical, computational and experimental methods. Within these objectives, the society organizes the EUROMECH Solid Mechanics Conference every three years. Following the very successful Conferences in Munich, Genoa, Stockholm, Metz, Thessaloniki and Budapest, the 7th EUROMECH Solid Mechanics Conference (ESMC2009) is now held in Lisbon. The purpose of this Conference is to provide opportunities for scientists and engineers to meet and to discuss current research, new concepts and ideas and establish opportunities for future collaborations in all aspects of Solid Mechanics. We invite you to be an active participant in this Conference and to contribute to any topic, or mini-symposium, of your scientific interest. By promoting a relaxed atmosphere for discussion and exchange of ideas we expect that new paths for research are stimulated and promoted and that new collaborations can be -

2017 the 2017 Paris Biennial

THE 2017 PARIS BIENNIAL THE GRAND PALAIS FROM MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11 THROUGH SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 2017 THE PROGRAM PRESS RELEASE — PARIS, MAY 15, 2017 THE BIENNALE PARIS PRESS RELEASE — PARIS, MAY 15, 2017 2 THE 2017 PARIS BIENNIAL NEW DATES TO ADAPT TO THE ANNUALIZATION OF THE PARIS BIENNIAL The Paris Biennial will be held from Monday, September 11 to Sunday, September 17, 2017 Vernissage: Sunday, September 10, 2017 With the announcement of its annualization, The Paris Biennial confirms its commitment to renewal and development, adopting a shorter, more dynamic format, while offering two potential weekends to French and international collectors and professionals. A CULTURAL AND ARTISTIC BACK-TO-SCHOOL WEEK IN 2017 The Paris Biennial also wishes to support and encourage the development of a more compelling cultural and artistic program to accompany Back-to-School Week. Ultimately, it is the idea of a week of artistic excellence that is sought by collectors and professionals, thus making Paris, in mid-September of every year, the principal cultural destination on an international scale. Organized in conjunction with The 2017 Paris Biennial, there will be two major exhibitions initiated by the Marmottan Monet and the Jacquemart André Museums, the former presenting a first-of-its-kind exhibition on « Monet, Collector » and the second exhibiting a tribute to Impressionism With «The Impressionist Treasures of the Ordrupgaard Collection - Sisley, Cézanne, Monet, Renoir, Gauguin.» THE BIENNALE PARIS PRESS RELEASE — PARIS, MAY 15, 2017 3 THE PARIS BIENNIAL AND « CHANTILLY ARTS AND ELEGANCE: RICHARD MILLE » In this spirit, The 2017 Paris Biennial has initiated a partnership with « Chantilly Arts and Elegance Richard Mille » which will, on September 10, 2017, present the most world’s most beautiful historical and collectors’ cars, along with couturiers’ creations, automobile clubs and the French Art of Living, at the Domaine de Chantilly. -

International Literary Program

PROGRAM & GUIDE International Literary Program LISBON June 29 July 11 2014 ORGANIZATION SPONSORS SUPPORT GRÉMIO LITERÁRIO Bem-Vindo and Welcome to the fourth annual DISQUIET International Literary Program! We’re thrilled you’re joining us this summer and eagerly await meeting you in the inimitable city of Lisbon – known locally as Lisboa. As you’ll soon see, Lisboa is a city of tremendous vitality and energy, full of stunning, surprising vistas and labyrinthine cobblestone streets. You wander the city much like you wander the unexpected narrative pathways in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the program’s namesake. In other words, the city itself is not unlike its greatest writer’s most beguiling text. Thanks to our many partners and sponsors, traveling to Lisbon as part of the DISQUIET program gives participants unique access to Lisboa’s cultural life: from private talks on the history of Fado (aka The Portuguese Blues) in the Fado museum to numerous opportunities to meet with both the leading and up-and- coming Portuguese authors. The year’s program is shaping up to be one of our best yet. Among many other offerings we’ll host a Playwriting workshop for the first time; we have a special panel dedicated to the Three Marias, the celebrated trio of women who collaborated on one of the most subversive books in Portuguese history; and we welcome National Book Award-winner Denis Johnson as this year’s guest writer. Our hope is it all adds up to a singular experience that elevates your writing and affects you in profound and meaningful ways. -

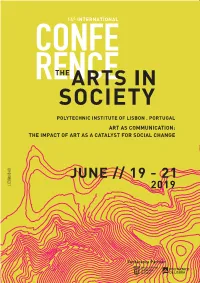

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

IN ASSOCIATION with CÂMARA MUNICIPAL DE LISBOA out There out There Beginner’S Survival Guide

IN ASSOCIATION WITH CÂMARA MUNICIPAL DE LISBOA Out there Out there Beginner’s survival guide Greet people with two kisses, forget the high heels, dodge the queues and bypass restaurants with food pictures by the front door. Here are our best tips to avoid tourist traps. You’re welcome. We speak the metro network, Don’t take just a creation is tricky terrain, have we been English whether you want risks: book to lure tourists with the city’s duped? As a rule of (and a bit to take a train or a table in. Creative, famous seven thumb, if the menu of everything an elevator – you’ll The recent boom but a deception hills and slippery is actually good, it else) avoid long queues. of trendy spaces nonetheless, so be Portuguese doesn’t need to be Portuguese people and experiences, aware, especially in pavement making paraded so much. are known for Expect kisses particularly in the the city centre, the the walking Keep this in mind their linguistic The Portuguese restaurant scene, most fertile ground experience (ideal when walking abilities, not to love kissing, and has made Lisbon’s for these traps. for discovering around Baixa, mention their cheek-kissing is gastronomy even every nook and Belém and other hospitality. You’re very much alive more appealing. Choose your cranny) into a tourist hotspots. very likely to find in Lisbon. So be With a caveat: if fado house real challenge. people who speak prepared to greet you’re not quick carefully Your breathing Don’t pay English better than (and be greeted by) enough, you’ll risk Fado is Portugal’s capacity may be ridiculous average, and maybe strangers with a not getting a table traditional music – tested to the max amounts even some French kiss on each cheek in the majority of nothing new here but, on the bright of money (especially the (or just on one, in popular venues – and it suddenly side, the city is for pressed older generations), posher settings). -

Lisbon, What the Tourist Should See

Fernando Pessoa Lisbon, what the tourist should see ... illustrated and geolocalized http://lisbon.pessoa.free.fr 1 of 48 What the Tourist Should See Over seven hills, which are as many points of observation whence the most magnificent panoramas may be enjoyed, the vast irregular and many-coloured mass of houses that constitute Lisbon is scattered. For the traveller who comes in from the sea, Lisbon, even from afar, rises like a fair vision in a dream, clear-cut against a bright blue sky which the sun gladdens with its gold. And the domes, the monuments, the old castles jut up above the mass of houses, like far-off heralds of this delightful seat, of this blessed region. The tourist's wonder begins when the ship approaches the bar, and, after passing the Bugio lighthouse 2 - that little guardian-tower at the mouth of the river built three centuries ago on the plan of Friar João Turriano -, the castled Tower of Belém 3 appears, a magnificent specimen of sixteenth century military architecture, in the romantic-gothic-moorish style (v. here ). As the ship moves forward, the river grows more narrow, soon to widen again, forming one of the largest natural harbours in the world with ample anchorage for the greatest of fleets. Then, on the left, the masses of houses cluster brightly over the hills. That is Lisbon . Landing is easy and quick enough ; it is effected at a point of the bank where means of transport abound. A carriage, a motor-car, or even a common electric trail, will carry the stranger in a few minutes right to the centre of the city. -

Art &Architectural History

Art & Architectural History The Age of Opus Anglicanum Colour A Symposium The Art and Science of edited by Michael A. Michael Illuminated Manuscripts The essays included here break new by S. Panayotova ground in the understanding of both The focus of the exciting and innova- liturgical and secular embroidery, tive exhibition to which this is the covering topics such as interesting companion volume is on color: it iconographic aspects found in Opus demonstrates and explains the acqui- Anglicanum; hitherto unpublished Limited quantity sition and chemistry of pigments, the data from the royal accounts of Edward Available while stocks last basic materials and constitution of the III related to commissions and pay- artist’s color palette, the technique ments to embroidery specialists and a detailed study of late medieval English and art of their application by the illuminator, and finally the understanding palls accompanied by a Handlist of the major extant examples. and aesthetic impact on the viewer. 240p, over 200 col illus (Harvey Miller Publishers, October 2016, Studies in 420p, 414 col illus (Harvey Miller Publishers, June 2016, Studies in Medieval and English Medieval Embroidery 1) hardcover, 9781909400412, $143.00. Early Renaissance Art History) paperback, 9781909400573, $65.00. Special Offer $115.00 Special Offer $52.00 Works in Collaboration Portraits After Existing Prototypes Jan Brueghel I & II by Koenraad Jonckheere by Christine van Mulders Rubens was mesmerized by faces. He studied physiognomy, Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder were collabo- which postulated that a person’s character could be read rating as painters as early as c. 1598, before Rubens’s stay in from their facial features. -

Sources for the History of Art Museums in Portugal» Final Report

PROJETHA Projects of the Institute of Art History Sources for the History of Art Museums in Portugal [PTDC/EAT-MUS/101463/2008 ] Final Report PROJETHA_Projects of the Institute of Art History [online publication] N.º 1 | «Sources for the History of Art Museums in Portugal» _ Final Report Editorial Coordination | Raquel Henriques da Silva, Joana Baião, Leonor Oliveira Translation | Isabel Brison Institut of Art History – Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa | 2013 PROJETHA_ Projects of the Institute of Art History SOURCES FOR THE HISTORY OF ART MUSEUMS IN PORTUGAL CONTENTS Mentioned institutions - proposed translations _5 PRESENTATION | Raquel Henriques da Silva _8 I. PARTNERSHIPS The partners: statements Instituto dos Museus e da Conservação | João Brigola _13 Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga | António Filipe Pimentel _14 Art Library of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation | Ana Paula Gordo _15 II . THE TASKS TASK 1. The origins of the Galeria Nacional de Pintura The origins of the Galeria Nacional de Pintura | Hugo Xavier _17 TASK 2. MNAA’s historical archives database, 1870-1962 The project “Sources…” at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga | Celina Bastos e Luís Montalvão _24 Report of the work undertaken at the Archive of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Research Fellowship | Andreia Novo e Ema Ramalheira _27 TASK 3. Exhibitions in the photographic collection of MNAA . The Photographic Archive at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. A historical sketch | Hugo d’Araújo _35 TASK 4. Inventory and study of the “Arrolamentos” of the Royal Palaces of Necessidades and Ajuda. The project “Sources…” at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda | PNA _52 Report of the work undertaken at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda. -

African Art at the Portuguese Court, C. 1450-1521

African Art at the Portuguese Court, c. 1450-1521 By Mario Pereira A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Mario Pereira VITA Mario Pereira was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1973. He received a B.A. in Art History from Oberlin College in 1996 and a M.A. in Art History from the University of Chicago in 1997. His master’s thesis, “The Accademia degli Oziosi: Spanish Power and Neapolitan Culture in Southern Italy, c. 1600-50,” was written under the supervision of Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Cummins. Before coming to Brown, Mario worked as a free-lance editor for La Rivista dei Libri and served on the editorial staff of the New York Review of Books. He also worked on the curatorial staff of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum where he translated the exhibition catalogue Raphael, Cellini and a Renaissance Banker: The Patronage of Bindo Altoviti (Milan: Electa, 2003) and curated the exhibition Off the Wall: New Perspectives on Early Italian Art in the Gardner Museum (2004). While at Brown, Mario has received financial support from the Graduate School, the Department of History of Art and Architecture, and the Program in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies. From 2005-2006, he worked in the Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design. In 2007-2008, he received the J. M. Stuart Fellowship from the John Carter Brown Library and was the recipient of an Andrew W. -

Pdf Catalogo Daciano D

DACIANODACOSTADESIGNER The Calouste Gulbenkian Ana Caetano | Ana Monteiro da Costa Fine Arts Service | António Aguiar | Carlos Alberto Silva Foundation thanks Manuel da Costa Cabral, Director | Carlos Costa | Carlos Reis | Carlos Lucília Alvoeiro, Deputy Director all the people Silva | Catarina Amaro da Costa | and institutions Catarina Monteiro da Costa | Commissioner Conceição and Alexandre Rebelo | João Paulo Martins that have made Dionísio Pestana | Fátima Libório | possible Eduardo Afonso Dias | Filipa Queiroz Production e Mello | Hermann Simon | João Rita da Fabiana the exhibition Soares | Joaquim Flórido | José Barata and the catalogue Moura | José Fernando Anacleto | Administrative Support José Manuel Torrão | Manuel Fernando Gaiaz Magalhães | Maria do Rosário Raposo | Maria do Rosário Santos | Maria Luísa Exhibition Design Cabral | Mário Brilhante | Margarida Atelier Daciano da Costa Ricardo Covões | Margarida Veiga | Cristina Sena da Fonseca Michael Schoomewagin | Pedro Martins Pereira | Rita Martinez | Mounting Coordination Rui Correia | Salette and José Brandão | Cristina Sena da Fonseca Sofia Nobre | Teresa Monteiro da Costa | Thomaz Rossner | Mounting Vasco Morgado Construções António Martins Sampaio ana, Aeroporto de Lisboa | Lighting design ana, Aeroporto Francisco Sá-Carneiro, fcg Central Services Porto | Biblioteca Nacional, Lisboa | Caixa Geral de Depósitos | Câmara Photo Enlargements Municipal de Lisboa | Carlton Alvor Textype (scanning) Hotel | Coliseu dos Recreios, Lisboa F. Costa (printing) | Companhia de Seguros Império | Crédito Predial Português | Crowne Graphic Design Plaza Resort Madeira, Funchal | Atelier B2 ddi, Difusão Internacional de José Brandão | Teresa Olazabal Cabral Design, Lda. | Fundação Centro Cultural de Belém | Hotel Altis, Transportation Lisboa | Hotel Madeira Palácio, rntrans, actividades transitárias Funchal | Interescritório. Mobiliário Internacional para Escritório, Insurance Lda. | Julcar, Augusto Carvalho Fidelidade Seguros & Flórido, Lda.