Zhang Yimou's Shanghai Triad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun's Work

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun’s Work By Yuanhai Zhu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Literature University of Alberta ©Yuanhai Zhu, 2015 ii Abstract This thesis explores decolonizing nationalism in early 20th century China through its literary embodiment. The topic in the thesis is Lu Xun, a canonical modern Chinese realist whose work is usually and widely discussed in scholarly works on Chinese literature and Chinese history in this period. Meanwhile, late 19th century and early 20th century, as the only semi-post-colonial period in China, has been investigated by many scholars via the theoretical lens of post-colonialism. The intellectual experience in China during this period is usually featured by the encounters between Eastern and Western intellectual worlds, the translation and appropriation of Western texts in the domestic Chinese intellectual world. In this view, Lu Xun’s work is often explored through his individualism which is in debt to Nietzsche, as well as other western romanticists and existentialists. My research purpose is to reinvestigate several central topics in Lu Xun’s thought, like the diagnosis of the Chinese national character, the post-colonial trauma, the appropriation of Nietzsche and the critique of imperialism and colonization. These factors are intertwined with each other in Lu Xun’s work and embody the historical situation in which the Chinese decolonizing nationalism is being bred and developed. Furthermore, by showing how Lu Xun’s appropriation of Nietzsche falls short of but also challenges its original purport, the thesis demonstrates the critique of imperialism that Chinese decolonizing nationalism initiates, as well as the aftermath which it brings to modern China. -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Comparative Literature by Xiangyang Liu Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Wai-lim Yip 2010 The Thesis of Xiangyang Liu is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents…………….…………………………………………………...… iv Abstract………………………………………………………………..…................ v Introduction…………………………………………………………… …………... 1 Chapter One A Modern City in the Perspective of Two Generations……………………………... 3 Chapter Two Urban Culture: Transmission and circling………………………………………….. 27 Chapter Three Negotiation with Shanghai’s Present and Past…………………………………….... 51 Conclusion………………………...………………………………………………… 86 Bibliography..……………………..…………………………………………… …….. 90 iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film by Xiangyang Liu Master of Arts in Comparative Literature University of California, San Diego, 2010 Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair This thesis is intended to investigate a series of films produced since the 1990s. All of these films deal with -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

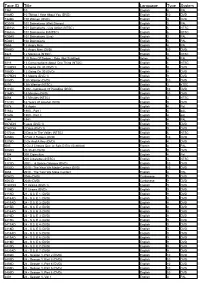

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Recommended Films: a Preparation for a Level Film Studies

Preparation for A-Level Film Studies: First and foremost a knowledge of film is needed for this course, often in lessons, teachers will reference films other than the ones being studied. Ideally you should be watching films regularly, not just the big mainstream films, but also a range of films both old and new. We have put together a list of highly useful films to have watched. We recommend you begin watching some these, as and where you can. There are also a great many online lists of ‘greatest films of all time’, which are worth looking through. Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 1941 Arguably the greatest film ever made and often features at the top of film critic and film historian lists. Welles is also regarded as one the greatest filmmakers and in this film: he directed, wrote and starred. It pioneered numerous film making techniques and is oft parodied, it is one of the best. It’s a Wonderful Life: Frank Capra, 1946 One of my personal favourite films and one I watch every Christmas. It’s a Wonderful Life is another film which often appears high on lists of greatest films, it is a genuinely happy and uplifting film without being too sweet. James Stewart is one of the best actors of his generation and this is one of his strongest performances. Casablanca: Michael Curtiz, 1942 This is a masterclass in storytelling, staring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. It probably has some of the most memorable lines of dialogue for its time including, ‘here’s looking at you’ and ‘of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine’. -

Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films

Travelling Films: Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films Goldsmiths College University of London PhD thesis (Cultural Studies) Ji Yeon Lee Abstract This thesis analyses western criticism, labelling practices and the politics of European international film festivals. In particular, this thesis focuses on the impact of western criticism on East Asian films as they attempt to travel to the west and when they travel back to their home countries. This thesis draws on the critical arguments by Edward Said's Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient (1978) and self-Orientalism, as articulated by Rey Chow, which is developed upon Mary Louise Pratt's conceptual tools such as 'contact zone' and 'autoethnography'. This thesis deals with three East Asian directors: Kitano Takeshi (Japanese director), Zhang Yimou (Chinese director) and 1m Kwon-Taek (Korean director). Dealing with Japanese, Chinese and Korean cinema is designed to show different historical and cultural configurations in which each cinema draws western attention. This thesis also illuminates different ways each cinema is appropriated and articulated in the west. This thesis scrutinises how three directors from the region have responded to this Orientalist discourse and investigates the unequal power relationship that controls the international circulation of films. Each director's response largely depends on the particular national and historical contexts of each country and each national cinema. The processes that characterise films' travelling are interrelated: the western conception of Japanese, Chinese or Korean cinema draws upon western Orientalism, but is at the same time corroborated by directors' responses. Through self-Orientalism, these directors, as 'Orientals', participate in forming and confirming the premises of western Orientalism. -

Teaching Post-Mao China Not Connected

RESOURCES FILM REVIEW ESSAY documentary style with which filmmaker Zhang Yimou is normally Teaching Post-Mao China not connected. This style—long shots of city scenes filled with people Two Classic Films and a subdued color palette—contribute to the viewer’s understand - ing of life in China in the early 1990s. The village scenes could be By Melisa Holden from anytime in twentieth century China, as the extent of moderniza - tion is limited. For example, inside peasants’ homes, viewers see Introduction steam spewing from characters’ mouths because of the severe cold The Story of Qiu Ju and Beijing Bicycle are two films that have been and lack of central heating. However, when Qiu Ju travels to the ur - used in classrooms since they were produced (1992 and 2001, respec - banized areas, it becomes obvious that the setting is the late twentieth tively). Today, these films are still relevant to high school and under - century. The film was shot only a couple of years after the Tiananmen graduate students studying history, literature, and related courses Square massacre in 1989. Zhang’s previous two films ( Ju Dou and about China, as they offer a picture of the grand scale of societal Raise the Red Lantern ) had been banned in China, but with The Story change that has happened in China in recent decades. Both films il - of Qiu Ju , Zhang depicts government officials in a positive light, lustrate contemporary China and the dichotomy between urban and therefore earning the Chinese government’s endorsement. One feels rural life there. The human issues presented transcend cultural an underlying tension through Qiu Ju’s search for justice, as if it is not boundaries and, in the case of Beijing Bicycle , feature young charac - only justice for her husband’s injured body and psyche, but also jus - ters that are the age of US students, allowing them to further relate to tice supposedly found through democracy. -

Perspectives in Flux

Perspectives in Flux Red Sorghum and Ju Dou's Reception as a Reflection of the Times Paisley Singh Professor Smith 2/28/2013 East Asian Studies Thesis Seminar Singh 1 Abstract With historical and critical approach, this thesis examined how the general Chinese reception of director Zhang Yimou’s Red Sorghum and Ju Dou is reflective of the social conditions at the time of these films’ release. Both films hold very similar diegeses and as such, each generated similar forms of filmic interpretation within the academic world. Film scholars such as Rey Chow and Sheldon Lu have critiqued these films as especially critical of female marginalization and the Oedipus complex present within Chinese society. Additionally, the national allegorical framing of both films, a common pattern within Chinese literary and filmic traditions, has thoroughly been explored within the Chinese film discipline. Furthermore, both films have been subjected to accusations of Self-Orientalization and Occidentalism. The similarity between both films is undeniable and therefore comparable in reference to the social conditions present in China and the changing structures within the Chinese film industry during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although Red Sorghum and Ju Dou are analogous, each received almost opposite reception from the general Chinese public. China's social and economic reform, film censorship, as well as the government’s intervention and regulation of the Chinese film industry had a heavy impact upon each film’s reception. Equally important is the incidence of specific events such as the implementation of the Open Door policy in the 1980s and 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. -

Foreignizing Translation on Chinese Traditional Funeral Culture in the Film Ju Dou

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 15, No. 1, 2017, pp. 47-50 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/9758 www.cscanada.org Foreignizing Translation on Chinese Traditional Funeral Culture in the Film Ju Dou PENG Xiamei[a],*; WANG Piaodi[a] [a]School of Foreign Languages, North China Electric Power University, Since Red Sorghum, the first film directed by him has Beijing, China. won the Golden Bear on February 23th, 1988, Zhang and *Corresponding author. his films produced a series of surprises for the Chinese Supported by The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central people and the world (Ban, 2003). He was said to be one Universities (JB2017074). of the most advanced figures in Chinese movies, and his films are regarded as a symbol of Chinese contemporary Received 15 April 2017; accepted 17 July 2017 culture. Published online 26 July 2017 In Zhang’s films, you’ll see a profound understanding of Chinese traditional feudal consciousness and strong Abstract critical spirit, which proves to be a strong sense of China is a country with more than five thousand years of history and life consciousness. It’s a peculiar landscape traditional cultures, which is broad and profound. With the of traditional folk customs and also praises for women’s increasing international status of China in recent years, rebellious spirit. The constant exploration and innovation more and more countries are interested in China and its in the film style and language represent the rise of a traditional culture as well. Film and television works, as new film trend. -

La Sociedad China a Través De Su Cine

E.G~oooo OCIOO 1'11 ~ ,qq~ ~ QC4 (j) 1q~t Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Campus Eugenio Garza Sada La sociedad china a través de su cine Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de Maestro en Educación con especialidad en Humanidades Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán Asesor: Dr. Víctor López Villafañe Monterrey, N.L. abril de 1997 INTITUTO TECNOLOGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY CAMPUS EUGENIO GARZA SADA La sociedad china a través de su cine Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de Maestro en Educación con especialidad en Humanidades Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán Asesor: Dr. Victor López Villafañe Monterrey, N.L. abril de 1997. A Martha, Alberto y Viridiana, por el tiempo robado. i Reconocimientos Al Dr. Victor López Villafañe, por el interés en este trabajo y por las palabras de aliento. Al ITESM Campus Sinaloa, por el apoyo nunca regateado. i i Resumen Tesis: "El cine chino a través de su cine". Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán. Asesor: Dr. Víctor López Villafañe. La presente investigación. llamada "La sociedad china a través de su cine", pretende arribar al conocimiento de los mecanismos sociales, culturales y de poder de la sociedad china en el siglo XX, todo ello a través del estudio de la cinematografía del país más poblado del mundo. Desde los albores de la industria hasta la inminente fusión de Hong Kong con la China continental, el cine ha sido un importantísimo medio cultural, de entretenimiento y de propaganda, que ha sido testigo y actor fundamental de las grandes transformaciones de este país.