Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun's Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGINEERING the Official Journal of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and Higher Education Press

ENGINEERING The official journal of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and Higher Education Press AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.12 ISSN: 2095-8099 DESCRIPTION . Engineering is an international open-access journal that was launched by the Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE) in 2015. Its aims are to provide a high-level platform where cutting- edge advancements in engineering R&D, current major research outputs, and key achievements can be disseminated and shared; to report progress in engineering science, discuss hot topics, areas of interest, challenges, and prospects in engineering development, and consider human and environmental well-being and ethics in engineering; to encourage engineering breakthroughs and innovations that are of profound economic and social importance, enabling them to reach advanced international standards and to become a new productive force, and thereby changing the world, benefiting humanity, and creating a new future. We are interested in: (1) News & Hightlights— This section covers engineering news from a global perspective and includes updates on engineering issues of high concern; (2) Views & Comments— This section is aimed at raising academic debates in scientific and engineering community, encouraging people to express new ideas, and providing a platform for the comments on some comprehensive issues; (3) Research— This section reports on outstanding research results in the form of research articles, reviews, perspectives, and short communications regarding critical engineering issues, and so on. All manuscripts must be prepared in English, and are subject to a rigorous and fair peer-review process. -

Inventing Chinese Buddhas: Identity, Authority, and Liberation in Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism

Inventing Chinese Buddhas: Identity, Authority, and Liberation in Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism Kevin Buckelew Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Kevin Buckelew All rights reserved Abstract Inventing Chinese Buddhas: Identity, Authority, and Liberation in Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism Kevin Buckelew This dissertation explores how Chan Buddhists made the unprecedented claim to a level of religious authority on par with the historical Buddha Śākyamuni and, in the process, invented what it means to be a buddha in China. This claim helped propel the Chan tradition to dominance of elite monastic Buddhism during the Song dynasty (960–1279), licensed an outpouring of Chan literature treated as equivalent to scripture, and changed the way Chinese Buddhists understood their own capacity for religious authority in relation to the historical Buddha and the Indian homeland of Buddhism. But the claim itself was fraught with complication. After all, according to canonical Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha was easily recognizable by the “marks of the great man” that adorned his body, while the same could not be said for Chan masters in the Song. What, then, distinguished Chan masters from everyone else? What authorized their elite status and granted them the authority of buddhas? According to what normative ideals did Chan aspirants pursue liberation, and by what standards did Chan masters evaluate their students to determine who was worthy of admission into an elite Chan lineage? How, in short, could one recognize a buddha in Song-dynasty China? The Chan tradition never answered this question once and for all; instead, the question broadly animated Chan rituals, institutional norms, literary practices, and visual cultures. -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

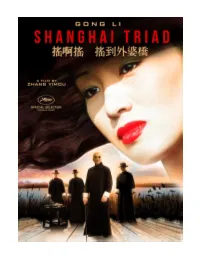

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

Understanding Chinese Film Culture at the End of the Twentieth Century : the Case of Not One Less by Zhang Yimou

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 4 Issue 2 Vol. 4.2 四卷二期 (2001) Article 8 1-1-2001 Understanding Chinese film culture at the end of the twentieth century : the case of Not one less by Zhang Yimou Sheldon H. LU University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Lu, S. H. (2001). Understanding Chinese film culture at the end of the twentieth century: The case of Not one less by Zhang Yimou. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 4(2), 123-142. This Discussion is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中 心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Understanding Chinese Film Culture at the End of the Twentieth Century: The Case of Not One Less by Zhang Yimou* Sheldon H. Lu Under the current political system, he [Zhang Yimou] feels that the biggest difference between himself and directors from foreign countries, Hong Kong, and Taiwan lies in the fact that <lwhen I receive a film script, the first thing I think about is not whether there will be an investor for the film, but how I can make the kind of film I want with the approval of the authorities.” Zeng Guang 巳y the end of the twentieth century, it has become increasingly apparent that the 1990s mark a new phase of cultural development distinct from that of the preceding decade. -

I Spy with My ›Little Eye‹«: GIS and Archaeological Perspectives on Eleventh-Century Song Envoy Routes in the Liao Empire Gwen P

»I Spy with my ›Little Eye‹«: GIS and Archaeological Perspectives on Eleventh-Century Song Envoy Routes in the Liao Empire Gwen P. Bennett* Archaeological data, combined with GIS analysis has given us new perspectives on eleventh century medieval period envoy missions from the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) to the Liao Empire (907-1125 CE). Lu Zhen and Wang Zhen were Song envoys sent in 1008 and 1012 by the Song to the Liao’s Middle Capital or Zhongjing, in present day Chifeng Inner Mongolia, the Peoples Republic of China (PRC). Lu Zhen recorded information about the route he tra- veled that allows us to locate it on administrative maps of the Song-Liao period and present day maps of the PRC. Viewshed analysis of the route combined with information Wang Zhen recorded about it lets us calculate population densities for an area that he passed through that can be used to extrapolate population density estimates from archaeological data for other areas in Chifeng. Viewshed analysis provides insights about the areal extent of the landscape and what man-made structures the envoys might have been able to see along the route during their travels. Combined, these analyses give us better insights into some of the concerns that the Liao had about these foreign missions crossing their territory and the steps they took to address them. Keywords: Liao Empire, Song Dynasty, archaeology, GIS, China, landscape analysis, viewsheds, optimal routes. Introduction Chinese historical sources tell us that in 1008, Lu Zhen was sent as an envoy from the Song Dynasty capital at Bianjing (modern day Kaifeng) to the Liao Empire (907-1125), centered in what is now Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China (Fig. -

Rui Liu Thesis (PDF 1MB)

Competition and Innovation: Independent Production in the Chinese TV Industry by Rui Liu Art BA /Journalism MA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2011 Competition and Innovation: Independent Production in Chinese TV Industry Competition and Innovation: Independent Production in Chinese TV Industry Abstract Independent television production is recognised for its capacity to generate new kinds of program content, as well as deliver innovation in formats. Globally, the television industry is entering into the post-broadcasting era where audiences are fragmented and content is distributed across multiple platforms. The effects of this convergence are now being felt in China, as it both challenges old statist models and presents new opportunities for content innovation. This thesis discusses the status of independent production in China, making relevant comparisons with independent production in other countries. Independent television production has become an important element in the reform of broadcasting in China in the past decade. The first independent TV production company was registered officially in 1994. While there are now over 4000 independent companies, the term „independent‟ does not necessarily constitute autonomy. The question the thesis addresses is: what is the status and nature of independence in China? Is it an appropriate term to use to describe the changing environment, or is it a misnomer? The thesis argues that Chinese independents operate alongside the mainstream state- owned system; they are „dependent‟ on the mainstream. Therefore independent television in China is a relative term. By looking at several companies in Beijing, mainly in entertainment, TV drama and animation, the thesis shows how the sector is injecting fresh ideas into the marketplace and how it plays an important role in improving innovation in many aspects of the television industry. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Kino gegen das Vergessen“ Die filmischen Metamorphosen des Zhang Yimou Verfasserin Stefanie Rauscher angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. a phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michael Gissenwehrer I want to bring Chinese film to the world Zhang Yimou Abstract In ihrem inhaltlichen Schwerpunkt gewährt die Arbeit einen umfangreichen Einblick in die Entwicklungsgeschichte des chinesischen Films von seinen Anfängen im ausgehenden 19.Jahrhundert bis in das frühe 21.Jahrhundert. In der konkreten Untersuchung des definierten Forschungsgegenstandes entsteht eine differenzierte Analyse der fundamentalen politischen Dimension hinsichtlich ihrer determinierenden Wirkung auf die Entfaltung kultureller Phänomene. Dabei wird besonders die sich wandelnde Positionierung des Mediums Film im Kontext der Etablierung des kommunistischen Staatssystems betrachtet. Anhand des innovativen Mediums werden die Parameter der politischen und sozialen Wirklichkeit - die eine umfassende Einschränkung der künstlerischen Freiheit bedeuten - mit der historischen Realität abgeglichen. Im Hinblick auf die signifikante Intermedialität des chinesischen Films wird der analytische Fokus ergänzend auf traditionelle Volkskünste – wie Pekingoper, chinesisches Schattenspiel und Sprechtheater verweisen, -

Dezember 2019

PROGRAMMINFORMATION NR.250 DEZEMBER 2019 SPECIALS ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD HOLLYWOODS PHILOSOPHIE MI 04.12.19 19:00 S.13 Ein Filmvortrag von Johannes Dezember Binotto Klostergasse 5 Im Sputnik Liestal 4051 Basel / beim Kunsthallengarten Im Fachwerk Allschwil www.stadtkinobasel.ch Im Marabu Gelterkinden SHOW PEOPLE Tel. 061 272 66 88 www.landkino.ch DO 19.12.19 21:00 S.13 Mit Live-Vertonung vom Ensemble Improcinema – Günter Buchwald (Piano), Bruno Spoerri (Saxophon), Marc Roos (Posaune), SÉLECTION LE BON FILM LANDKINO S.11 Frank Bockius (Schlagzeug) S.27 «A DOG CALLED S.24 BRITISH HEIST MOVIES MONEY» VON ONCE UPON A | ONCE UPON A TIME SPECIAL ZHANG YIMOU SEAMUS MURPHY IN HOLLYWOOD | SÉLECTION LE BON COMING HOME BASLER FILMTREFF DO 05.12.19 18:00 S.23 DIE BASLER KAMERA- TIME IN FILM S.20 Mit einem einführenden Vortrag FRAU ALINE LÁSZLÓ ABSCHIEDSFILM von Luc Schaedler – DEN MOMENT S.26 «À BOUT DE SOUFFLE» EIN FANGEN ODER HOLLYWOOD – EIN ABSCHIED UND SPECIAL BASLER FILMTREFF BILDER INSZENIEREN? S.18 EIN NEUBEGINN VAKUUM MO 09.12.19 18:30 ZHANGLEBEN! YIMOU S.23 Im Rahmen des Basler Filmtreffs gibt die Kamerafrau Aline László Einblick in ihre Arbeitsweise. SPECIAL ABSCHIEDSFILM À BOUT DE SOUFFLE Mi 11.12.19 18:30 S.26 Im Anschluss Apéro. SONNTAG 13:15 ZHANG YIMOU JU DOU S.20 China/Japan 1990 95 Min. Farbe. 35 mm. OV/d/f ZHANG YIMOU, YANG FENGLIANG1 15:15 ONCE UPON A TIME SUNSET BOULEVARD S.14 USA 1950 110 Min. sw. DCP. E/d BILLY WILDER 17:30 ZHANG YIMOU TO LIVE S.20 China/Hongkong 1994 133 Min. -

La Sexualité, La Violence Et Le Politiquement Correct Dans Les Films De Zhang Yimou Wei Sun

Les tabous et l’autocensure : la sexualité, la violence et le politiquement correct dans les films de Zhang Yimou Wei Sun To cite this version: Wei Sun. Les tabous et l’autocensure : la sexualité, la violence et le politiquement correct dans les films de Zhang Yimou. Art et histoire de l’art. Université Paul Valéry - Montpellier III, 2019. Français. NNT : 2019MON30003. tel-02918132 HAL Id: tel-02918132 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02918132 Submitted on 20 Aug 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ! ! ! Délivré par UNIVERSITÉ PAUL-VALÉRY MONTPELLIER III Préparée au sein de l’école doctorale 58 Et de l’unité de recherche RIRRA21 Spécialité : Études cinématographiques et audiovisuelles Présentée par SUN Wei Les tabous et l’autocensure: La sexualité, la violence et le politiquement correct dans les films de Zhang Yimou !"#$%&% Soutenue le 1 ! mars 2019 devant le jury composé de Monsieur Michel CADÉ, Professeur à l’Université de Perpignan, Président du jury Monsieur Angel QUINTANA, Professeur à l’Université de Gerone (Espagnol), -

Shanghai Triad (1995)

Shanghai Triad (1995) FILM FESTIVAL REVIEW; Soulfully Speaking A Universal Language Felt by the Oppressed By JANET MASLIN Published: September 29, 1995 OPENING night of this year's New York Film Festival should have been triumphant for the Chinese director Zhang Yimou, a film maker whose rare soulfulness and purity of vision have earned him a well-deserved place on the world stage. Instead, overshadowed by China's refusal to allow Mr. Zhang to appear here tonight, the event becomes a more Pyrrhic victory. Although his new film, "Shanghai Triad," is narrowed by the same atmosphere of political repression that keeps Mr. Zhang away this evening, it still speaks the stirring universal language of his bolder work. The power of that artistry is a reproach to those who deny it free reign. "Shanghai Triad" must be seen in its proper context, as a film that was shut down during production because of Mr. Zhang's political problems over "To Live," which addressed itself to recent Chinese history with an openly critical tone. (The cancellation of his trip to New York had nothing to do with his own work. Instead, this was retaliation against the festival for refusing to drop "The Gate of Heavenly Peace," an American documentary about the 1989 showdown in Tiananmen Square in Beijing.) In the aftermath of making "To Live," Mr. Zhang has acknowledged, he was not out to seek further trouble. Hence his choice of "Shanghai Triad," which may be as close as this great director can come to making a conventional film. Set in 1930, it tells of a powerful gangster and his bored, capricious mistress, a fallen woman who ultimately comes to know and regret her mistakes. -

Early Chinese Photographers from 1840 to 1870: Innovation and Adaptation in the Development of Chinese Photography

EARLY CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHERS FROM 1840 TO 1870: INNOVATION AND ADAPTATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHY By SHI CHEN A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Shi Chen 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my parents for their unconditional love and support. I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. Guolong Lai for his incredibly insightful and patient guidance from the conception to the very gradual completion of what began as a seemingly endless thesis project. I would also like to thank my committee member, Dr. Glenn Willumson for his great interest and support from the selection of my thesis project to the end product. I would like to thank Ms. Dixie Neilson and Dr. Amy Vigilante for the warmness they gave me over the past three years. Additionally, I owe my countless thanks to the following individuals, without whom this project would not have been possible: Dr. Frances Terpak, Beth Guynn, John Kiffe, and Teresa Mesquit at the Getty Research Institute; Dr. Raymond Lum at the Harvard East Asian Yanching Library; Dr. Phillip Prodger at the Peabody Essex Museum; and Claartje van Dijk at the International Center of Photography. Finally, I want to thank my friends, especially Zhenning Zhang, Lingling Xiang, Litao Lu, Zhen Liu, Ruth Sheng, Yue Zhang, Ruixin Jiang, Elizabeth Coker, Claudia Cervantes, Chole Smith, Sarah Mullersman, Oaklianna Brown and Dushanthi Jayawardena for helping me maintain both my sanity and sense of humor over the course of the last three years. -

Increasing Visibility of Lesbian Desire in Chinese Cinemas By

Shaping a New Identity: Increasing Visibility of Lesbian Desire in Chinese Cinemas by Virginia Mulky Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Submitted to the Undergraduate Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE This thesis was presented by Virginia Mulky It was defended on April 1, 2011 and approved by Alice Kuzniar, Professor, Germanic and Slavic Studies, University of Waterloo Xinmin Liu, Assistant Professor, East Asian Languages and Literatures Neepa Majumdar, Associate Professor, English and Film Studies Thesis Director: Mark Lynn Anderson, Associate Professor, English and Film Studies ii Copyright © by Virginia Mulky 2011 iii Shaping a New Identity: Increasing Visibility of Lesbian Desire in Chinese Cinemas Virginia Mulky, B.Phil. University of Pittsburgh, 2011 In recent years there has been a noticeable increase in Chinese-language films about lesbian romances. Many of these films have found commercial and critical success in Chinese markets such as Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as honors at international film festivals.In order to analyzes how these films reflect and shape Chinese lesbian identity, this thesis considers how a range of contemporary Chinese-language films produced in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and abroad deploys the figure of the lesbian. In particular, this study examines the production of such films by Chinese cultures outside of Mainland China as a means of promoting an alternative, inclusive Chinese identity in opposition to Mainland censorship. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 8 LOVE’S LONE FLOWER: RE-IMAGINING THE PAST...................................................