Rui Liu Thesis (PDF 1MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun's Work

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun’s Work By Yuanhai Zhu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Literature University of Alberta ©Yuanhai Zhu, 2015 ii Abstract This thesis explores decolonizing nationalism in early 20th century China through its literary embodiment. The topic in the thesis is Lu Xun, a canonical modern Chinese realist whose work is usually and widely discussed in scholarly works on Chinese literature and Chinese history in this period. Meanwhile, late 19th century and early 20th century, as the only semi-post-colonial period in China, has been investigated by many scholars via the theoretical lens of post-colonialism. The intellectual experience in China during this period is usually featured by the encounters between Eastern and Western intellectual worlds, the translation and appropriation of Western texts in the domestic Chinese intellectual world. In this view, Lu Xun’s work is often explored through his individualism which is in debt to Nietzsche, as well as other western romanticists and existentialists. My research purpose is to reinvestigate several central topics in Lu Xun’s thought, like the diagnosis of the Chinese national character, the post-colonial trauma, the appropriation of Nietzsche and the critique of imperialism and colonization. These factors are intertwined with each other in Lu Xun’s work and embody the historical situation in which the Chinese decolonizing nationalism is being bred and developed. Furthermore, by showing how Lu Xun’s appropriation of Nietzsche falls short of but also challenges its original purport, the thesis demonstrates the critique of imperialism that Chinese decolonizing nationalism initiates, as well as the aftermath which it brings to modern China. -

KANG-THESIS.Pdf (614.4Kb)

Copyright by Jennifer Minsoo Kang 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jennifer Minsoo Kang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar Karin G. Wilkins From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 by Jennifer Minsoo Kang, B.A.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my family; my parents, sister and brother Abstract From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 Jennifer Minsoo Kang, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar The format program trade has grown rapidly in the past decade and has become an important part of the global television market. This study aimed to give an understanding of this phenomenon by examining how global formats enter and become incorporated into the national media market through a case study analysis on the Korean format market. Analyses were done to see how the historical background influenced the imported format flows, how the format flows changed after the media liberalization period, and how the format uses changed from illegal copying to partial formats to whole licensed formats. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the global format program flows are different from the whole ‘canned’ program flows because of the adaptation processes, which is a form of hybridity, the formats go through. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

On the Rise and Decline of Wulitou 无厘头's Popularity in China

The Act of Seeing and the Narrative: On the Rise and Decline of Wulitou 无厘头’s Popularity in China Inaugural dissertation to complete the doctorate from the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne in the subject Chinese Studies presented by Wen Zhang ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks go to my supervisors, Prof. Dr. Stefan Kramer, Prof. Dr. Weiping Huang, and Prof. Dr. Brigitte Weingart for their support and encouragement. Also to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne for providing me with the opportunity to undertake this research. Last but not least, I want to thank my friends Thorsten Krämer, James Pastouna and Hung-min Krämer for reviewing this dissertation and for their valuable comments. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 0.1 Wulitou as a Popular Style of Narrative in China ........................................................... 1 0.2 Story, Narrative and Schema ................................................................................................. 3 0.3 The Deconstruction of Schema in Wulitou Narratives ................................................... 5 0.4 The Act of Seeing and the Construction of Narrative .................................................... 7 0.5 The Rise of the Internet and Wulitou Narrative .............................................................. 8 0.6 Wulitou Narrative and Chinese Native Cultural Context .......................................... -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

LETTERS to the EDITOR. Middle Cerebral Artery Tortuosity Associated

J Neurosurg 130:1763–1788, 2019 Neurosurgical Forum LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Middle cerebral artery tortuosity tective factors against aneurysm formation.” Nevertheless, according to that explanation, it can be inferred that the associated with aneurysm incidence of aneurysms in patients with local tortuosity development should be decreased rather than increased. Therefore, it would be better for the authors to provide an in-depth ex- planation about the above results and arguments. TO THE EDITOR: We read with great interest the ar- Second, the authors stated, “There are a few rare ge- ticle by Kliś et al.2 (Kliś KM, Krzyżewski RM, Kwinta netic syndromes that are linked to the presence of vessel BM, et al: Computer-aided analysis of middle cerebral tortuosity, such as artery tortuosity syndrome or Loeys- artery tortuosity: association with aneurysm develop- Dietz syndrome.” The genetic syndromes they mention ment. J Neurosurg [epub ahead of print May 18, 2018; are systemic lesions involving multiple parts of vessels DOI: 10.3171/2017.12.JNS172114]). The authors conclude of the body and therefore often involve multiple intracra- that “an increased deviation of the middle cerebral artery nial aneurysms.1,3,5 However, this article did not provide (MCA) from a straight axis (described by relative length detailed information on the characteristics of intracranial [RL]), a decreased sum of all MCA angles (described by aneurysms, for example, the incidence of multiple aneu- sum of angle metrics [SOAM]), a local increase of the rysms, the specific sites of the MCA aneurysms (M1, M2, MCA angle heterogeneity, and an increase in changes in M3, M4), and the size of the aneurysms, etc. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Xi Tian August 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Yenna Wu Copyright by Xi Tian 2014 The Dissertation of Xi Tian is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 by Xi Tian Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2014 Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson My dissertation rethinks satire and redefines our understanding of it through the examination of works from the 1930s and 1940s. I argue that the fluidity of satiric writing in the 1930s and 1940s undermines the certainties of the “satiric triangle” and gives rise to what I call, variously, self-satire, self-counteractive satire, empathetic satire and ambiguous satire. It has been standard in the study of satire to assume fixed and fairly stable relations among satirist, reader, and satirized object. This “satiric triangle” highlights the opposition of satirist and satirized object and has generally assumed an alignment by the reader with the satirist and the satirist’s judgments of the satirized object. Literary critics and theorists have usually shared these assumptions about the basis of satire. I argue, however, that beginning with late-Qing exposé fiction, satire in modern Chinese literature has shown an unprecedented uncertainty and fluidity in the relations among satirist, reader and satirized object. -

Correlation Between the Cerebralization, Astroglial Architecture and Blood-Brain Barrier Composition in Chondrichthyes

Correlation between the cerebralization, astroglial architecture and blood-brain barrier composition in Chondrichthyes Ph.D. thesis Csilla Ari Semmelweis University Neurobiology School of Doctoral Studies Supervisor: Dr. Mihály Kálmán, Ph.D. Reviewers: Dr. Anna Kiss, Ph.D. Dr. Klára Matesz, DSc Committee of Final Examination: Chairman: Dr. Béla Vígh, DSc Members: Dr.Tibor Wenger, DSc Dr. Tamás Röszer, Ph.D. Budapest, 2008. Introduction Comparison of cerebralization in chondrichthyan fishes with that of other Representing a separate radiation of vertebrates, Chondrichthyes underwent a vertebrate groups has been made by constructing ‘minimum convex polygons’ to unique brain evolution. They display a wide range of cerebralization, differences enclose data points in a double logarithmic scale of a brain weight/body weight in the glial architecture and in the composition of the blood-brain barrier. Some plot by Jerison (1973). The same method was applied to additional data, by groups of Chondrichthyes, and also some of their brain parts were neglected in Northcutt (1977, 1978, 1981) and Smeets et al. (1983). According to such previous neuroanatomical studies and only few immunohistological techniques analysis, chondrichthians exhibit a wide range of cerebralization. The brain were applied in order to describe the glial pattern of cartilaginous fishes. weight/body weight ratios in batoids and galeomorph sharks are two to six times Class of cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) comprises two major divisions larger than in squalomorph sharks. Within the superorder Batoidea (skates and (subclasses), the Elasmobranchii (sharks, skates and rays) and the Holocephali rays), Rajiformes (skates) have relatively low brain weight/body weight ratios, (chimaeras or ratfishes or ghostsharks). -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

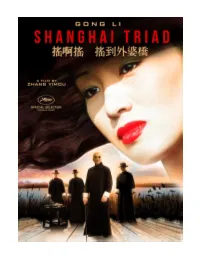

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Trans/National Chinese Bodies Performing Sex, Health, and Beauty in Cinema and Media a Diss

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Trans/national Chinese Bodies Performing Sex, Health, and Beauty in Cinema and Media A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Mila Zuo 2015 © Copyright by Mila Zuo 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Trans/national Chinese Bodies Performing Sex, Health, and Beauty in Cinema and Media by Mila Zuo Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Kathleen A. McHugh, Chair This dissertation explores the connections between Chinese body cultures and transnational screen cultures by tracing the Chinese body through representation in contemporary cinema and media in the post-Mao era. Images of Chinese bodies participate in the audio-visual manufacture of desire and pleasure, and ideas of “Chinese- ness” endure through repetitive, mediated performance. This dissertation examines how representations of sex, health, and beauty are mediated by social, cultural, and political belief systems, and how cine/televisual depictions of the body also, in turn, mediate gender, cultural, racial and ethnic identifications within and across national boundaries. The bodily practices and behaviors in the quotidian arenas of sex, health, and beauty reflect the internalization of culture and the politics of identity construction. This dissertation is interested in how the pleasures of cinema relate to the politics of the body, ii and how the pleasures of the body relate to the politics of cinema. -

World Cultural Review 100

Vol-1; Issue-4 January - February 2020 Delhi RNI No.: DELENG/2019/78107 WORLD CULTURAL REVIEW www.worldcultureforum.org.in 100 OVER A ABOUT US World Culture Forum is an international Cultural Organization who initiates peacebuilding and engages in extensive research on contemporary cultural trends across the globe. We firmly believe that peace can be attained through dialogue, discussion and even just listening. In this spirit, we honor individuals and groups who are engaged in peacebuilding process, striving to establish a boundless global filmmaking network, we invite everyone to learn about and appreciate authentic local cultures and value cultural diversity in film. Keeping in line with our mission, we create festivals and conferences along with extensively researched papers to cheer creative thought and innovation in the field of culture as our belief lies in the idea – “Culture Binds Humanity. and any step towards it is a step towards a secure future. VISION We envisage the creation of a world which rests on the fundamentals of connected and harmonious co-existence which creates a platform for connecting culture and perseverance to build solidarity by inter-cultural interactions. MISSION We are committed to providing a free, fair and equal platform to all cultures so as to build a relationship of mutual trust, respect, and cooperation which can achieve harmony and understand different cultures by inter-cultural interactions and effective communications. RNI. No.: DELENG/2019/78107 World Cultural Review CONTENTS Vol-1; Issue-4, January-February 2020 100 Editor Prahlad Narayan Singh [email protected] Executive Editor Ankush Bharadwaj [email protected] Managing Editor Shiva Kumar [email protected] Associate Ankit Roy [email protected] Legal Adviser Dr. -

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins In

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins in Experimental Photography from China Xavier Ortells-Nicolau Directors de tesi: Dr. Carles Prado-Fonts i Dr. Joaquín Beltrán Antolín Doctorat en Traducció i Estudis Interculturals Departament de Traducció, Interpretació i d’Estudis de l’Àsia Oriental Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 ii 工地不知道从哪天起,我们居住的城市 变成了一片名副其实的大工地 这变形记的场京仿佛一场 反复上演的噩梦,时时光顾失眠着 走到睡乡之前的一刻 就好像门面上悬着一快褪色的招牌 “欢迎光临”,太熟识了 以到于她也真的适应了这种的生活 No sé desde cuándo, la ciudad donde vivimos 比起那些在工地中忙碌的人群 se convirtió en un enorme sitio de obras, digno de ese 她就像一只蜂后,在一间屋子里 nombre, 孵化不知道是什么的后代 este paisaJe metamorfoseado se asemeja a una 哦,写作,生育,繁衍,结果,死去 pesadilla presentada una y otra vez, visitando a menudo el insomnio 但是工地还在运转着,这浩大的工程 de un momento antes de llegar hasta el país del sueño, 简直没有停止的一天,今人绝望 como el descolorido letrero que cuelga en la fachada de 她不得不设想,这能是新一轮 una tienda, 通天塔建造工程:设计师躲在 “honrados por su preferencia”, demasiado familiar, 安全的地下室里,就像卡夫卡的鼹鼠, de modo que para ella también resulta cómodo este modo 或锡安城的心脏,谁在乎呢? de vida, 多少人满怀信心,一致于信心成了目标 en contraste con la multitud aJetreada que se afana en la 工程质量,完成日期倒成了次要的 obra, 我们这个时代,也许只有偶然性突发性 ella parece una abeja reina, en su cuarto propio, incubando quién sabe qué descendencia. 能够结束一切,不会是“哗”的一声。 Ah, escribir, procrear, multipicarse, dar fruto, morir, pero el sitio de obras sigue operando, este vasto proyecto 周瓒 parece casi no tener fecha de entrega, desesperante, ella debe imaginar, esto es un nuevo proyecto, construir una torre de Babel: los ingenieros escondidos en el sótano de seguridad, como el topo de Kafka o el corazón de Sión, a quién le importa cuánta gente se llenó de confianza, de modo que esa confianza se volvió el fin, la calidad y la fecha de entrega, cosas de importancia secundaria.