Understanding Chinese Film Culture at the End of the Twentieth Century : the Case of Not One Less by Zhang Yimou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun's Work

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun’s Work By Yuanhai Zhu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Literature University of Alberta ©Yuanhai Zhu, 2015 ii Abstract This thesis explores decolonizing nationalism in early 20th century China through its literary embodiment. The topic in the thesis is Lu Xun, a canonical modern Chinese realist whose work is usually and widely discussed in scholarly works on Chinese literature and Chinese history in this period. Meanwhile, late 19th century and early 20th century, as the only semi-post-colonial period in China, has been investigated by many scholars via the theoretical lens of post-colonialism. The intellectual experience in China during this period is usually featured by the encounters between Eastern and Western intellectual worlds, the translation and appropriation of Western texts in the domestic Chinese intellectual world. In this view, Lu Xun’s work is often explored through his individualism which is in debt to Nietzsche, as well as other western romanticists and existentialists. My research purpose is to reinvestigate several central topics in Lu Xun’s thought, like the diagnosis of the Chinese national character, the post-colonial trauma, the appropriation of Nietzsche and the critique of imperialism and colonization. These factors are intertwined with each other in Lu Xun’s work and embody the historical situation in which the Chinese decolonizing nationalism is being bred and developed. Furthermore, by showing how Lu Xun’s appropriation of Nietzsche falls short of but also challenges its original purport, the thesis demonstrates the critique of imperialism that Chinese decolonizing nationalism initiates, as well as the aftermath which it brings to modern China. -

Karrin E. Wilks, Interim President, BMCC Monday | March 30, 2020

Welcoming Remarks: Karrin E. Wilks, Interim President, BMCC Monday | March 30, 2020 | 9:15 am- 9:30 am | Theatre 2 Opening Remarks: Maria Enrico, Chair, Modern Languages Department Monday | March 30, 2020 | 9:30 am-9.45 am | Theatre 2 Wonder Women! The Untold Story of American Superheroines Monday | March 30, 2020 | 10: 00 am-11: 30 pm | Theatre 2 Bande de filles | Girlhood Monday | March 30, 2020 | 12:00 pm- 2: 30 pm | Theatre 2 Bellisima Monday | March 30, 2020 | 3.00 pm-4:45 pm | Theatre 2 Welcoming Tuesday | March 31, 2020 | 9:15 am- 9:30 am | Theatre 2 وجدة | Wadjda Tuesday | March 31, 2020 | 9:30 am-11:30 am | Theatre 2 Not One Less | 一个都不能少 | Yīgè dōu bùnéng shǎo Tuesday | March 31, 2020 | 12:00 pm-2:30 pm | Theatre 2 Roma Tuesday | March 31, 2020 | 3:00 pm-5:40 pm | Theatre 2 Closing Write a review of your favorite movie O U R P E O P L E MARIA ENRICO (CHAIR) · RAFAEL CORBALÁN · EDA HENAO · SILVIA ÁLVAREZ-OLARRA · MARGARET CARSON · If you want to write reviews that carry PETER CONSENSTEIN · RACHEL CORKLE · ·BERENICE DARWICH · MARÍA DE LOS ÁNGELES DONOSO MACAYA · some authority, then you need to learn everything you can. GERMÁN GARRIDO · EVELIN GAMARRA-MARTÍNEZ · AINOA ÍÑIGO· LAURIE LOMASK · LING (EMILY) LUO · Some believe that in order to be a truly good film critic you must ALICIA PERDOMO H. · PATRIZIA COMELLO PERRY · SILVIA ROIG · SOPHIE MARÍÑEZ · JOHN THOMAS MEANS · have worked as a director, or that in order to review music you CHUN-YI PENG · NIDIA PULLÉS-LINARES · ÁLISTER RAMÍREZ-MÁRQUEZ · MARILYN RIVERA · FANNY M. -

After the Livestock Revolution Free-Grazing Ducks and Influenza Uncertainties in South China

ARTICLE After the livestock revolution Free-grazing ducks and influenza uncertainties in South China Lyle Fearnley Abstract Since the 1970s, virologists have pointed to South China as a hypothetical ‘epicenter’ of influenza pandemics. In particular, several key studies highlighted the farming practice of ‘free-grazing’ ducks (fangyang) as the crucial ecological factor driving the emergence of new flu viruses. Following the emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in 1997 and 2004, free-grazing ducks became a primary target of biosecurity interventions from global health agencies and China’s national government. This article compares the global health ‘problematization’ of free-grazing ducks as a pandemic threat with the manner in which duck farmers around Poyang Lake, China, engage with the dangers of disease in their flocks. Showing how both global health experts and duck farmers configure the uncertainty of disease against ideal modes of ordering the relations among species, I conclude by examining how these two problematizations interact in ways that mutually intensify – rather than moderate – uncertainty. Keywords pandemics, influenza, agrarian change, multispecies, human-animal relations, uncertainty Medicine Anthropology Theory 5 (3): 72–98; https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.5.3.378. © Lyle Fearnley, 2018. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Medicine Anthropology Theory 73 Out in the rice fields and waterways that surround China’s enormous Poyang Lake, located in southern Jiangxi Province, ducks are a common sight. The lowland environment of the lake region, filled with canals and small ponds, is certainly suitable for the husbandry of waterfowl. Provincial planning reports from the 1980s called for the lake region to be developed as a ‘production base’ for commercial waterfowl (Studies on Poyang Lake Editorial Committee 1988). -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 123 2nd International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (ICESAME 2017) Study on the Contribution of Xiling's Poetry to Poetry Flourished in Earlier Qing Dynasty Liping Gu The Engineering & Technical College of Chengdu University of Technology, Leshan, Sichuan, 614000 Keywords: Xiling Poetry, Poetry Flourished, Qing Dynasty Abstract. At the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, Xiling language refers to the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty in Xiling a word activities of the word group, including Xiling capital of the poet, including the official travel in Xiling’s poetry, is a geographical, The family, the teacher as a link to the end of the alliance as an opportunity, while infiltration Xiling heavy word tradition, in the late Ming Dynasty poetry specific poetry language formation in the group of people. They are more rational and objective theory, especially emphasizing the essence of the word speculation, pay attention to the word rhyme and the creation of the law of the summary, whether it is theory or creation, the development of the Qing Dynasty have far-reaching impact. In short, the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty Xiling language in the word from the yuan, the decline since the turn of the Qing Dynasty to the revival of the evolution of this process is a can not be ignored. Introduction The formation and development of the Xiling School are inseparable from the development of the same language. Many people regard the Western Cold School as the rise of the cloud and even as part of the cloud. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films

Travelling Films: Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films Goldsmiths College University of London PhD thesis (Cultural Studies) Ji Yeon Lee Abstract This thesis analyses western criticism, labelling practices and the politics of European international film festivals. In particular, this thesis focuses on the impact of western criticism on East Asian films as they attempt to travel to the west and when they travel back to their home countries. This thesis draws on the critical arguments by Edward Said's Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient (1978) and self-Orientalism, as articulated by Rey Chow, which is developed upon Mary Louise Pratt's conceptual tools such as 'contact zone' and 'autoethnography'. This thesis deals with three East Asian directors: Kitano Takeshi (Japanese director), Zhang Yimou (Chinese director) and 1m Kwon-Taek (Korean director). Dealing with Japanese, Chinese and Korean cinema is designed to show different historical and cultural configurations in which each cinema draws western attention. This thesis also illuminates different ways each cinema is appropriated and articulated in the west. This thesis scrutinises how three directors from the region have responded to this Orientalist discourse and investigates the unequal power relationship that controls the international circulation of films. Each director's response largely depends on the particular national and historical contexts of each country and each national cinema. The processes that characterise films' travelling are interrelated: the western conception of Japanese, Chinese or Korean cinema draws upon western Orientalism, but is at the same time corroborated by directors' responses. Through self-Orientalism, these directors, as 'Orientals', participate in forming and confirming the premises of western Orientalism. -

10883-APG-Portland Place School-Strive Year 9 V4.Indd

STRIVE YEAR 9 WHY? FOSTER YOUR PASSION STRETCH AND ENTHUSIASM YOUR FOR THE SUBJECTS LEARNING YOU LOVE IN FUN OUTSIDE THE AND EXCITING CLASSROOM. WAYS. BEGIN THINKING AND EXPERIMENTING DEVELOP WITH DIFFERENT STRATEGIES FOR WAYS OF INDEPENDENT LEARNING. LEARNING WHICH WILL BE ESSENTIAL FOR SUCCESS. Portland Place | Strive | Year 9 | Why? 3 We will give you recommendations based on what you can: STRIVE READ WATCH At Portland Place we want to provide you with the opportunity to: CONTENTS • Excite and broaden your mind on your favourite topics and subjects. ART 6 Stretch your learning far beyond the classroom. • COMPUTER SCIENCE 7 • Empower you to set your own learning direction. DRAMA 8 • Inspire and motivate you. DESIGN TECHNOLOGY 9 We want to provide you with the opportunity to explore topics ENGLISH 10 and issues further, to develop a sense of questioning and GEOGRAPHY 11 curiosity. When we are curious, we see things differently, making HISTORY WWI 12 connections and experiencing moments of insight and meaning — all of which provide the foundation for rich and satisfying HISTORY WWII 13 life experiences. HISTORY HOLOCAUST 14 This booklet outlines The Strive Programme, allowing you to HISTORY THE COLD WAR 14 harness your curiosity and deepen your interest and engagement HISTORY CIVIL RIGHTS 15 of a particular subject through closer study. Each subject has MATHEMATICS 16 suggestions about things you can,WATCH, READ, LISTEN, SEE LISTEN SEE MATHS & ARTS 17 AND DO to foster your passion and enthusiasm for the subjects you love and develop strategies for independent learning. The MUSIC 18 - 19 tasks are designed to be done at your pace and in your own time. -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin. -

Perspectives in Flux

Perspectives in Flux Red Sorghum and Ju Dou's Reception as a Reflection of the Times Paisley Singh Professor Smith 2/28/2013 East Asian Studies Thesis Seminar Singh 1 Abstract With historical and critical approach, this thesis examined how the general Chinese reception of director Zhang Yimou’s Red Sorghum and Ju Dou is reflective of the social conditions at the time of these films’ release. Both films hold very similar diegeses and as such, each generated similar forms of filmic interpretation within the academic world. Film scholars such as Rey Chow and Sheldon Lu have critiqued these films as especially critical of female marginalization and the Oedipus complex present within Chinese society. Additionally, the national allegorical framing of both films, a common pattern within Chinese literary and filmic traditions, has thoroughly been explored within the Chinese film discipline. Furthermore, both films have been subjected to accusations of Self-Orientalization and Occidentalism. The similarity between both films is undeniable and therefore comparable in reference to the social conditions present in China and the changing structures within the Chinese film industry during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although Red Sorghum and Ju Dou are analogous, each received almost opposite reception from the general Chinese public. China's social and economic reform, film censorship, as well as the government’s intervention and regulation of the Chinese film industry had a heavy impact upon each film’s reception. Equally important is the incidence of specific events such as the implementation of the Open Door policy in the 1980s and 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. -

Download Full Textadobe

JapanFocus http://japanfocus.org/articles/print_article/3285 Charter 08, the Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism Feng Chongyi The publication of Charter 08 in China at the end of 2008 was a major event generating headlines all over the world. It was widely recognized as the Chinese human rights manifesto and a landmark document in China’s quest for democracy. However, if Charter 08 was a clarion call for the new march to democracy in China, its political impact has been disappointing. Its primary drafter Liu Xiaobo, after being kept in police custody over one year, was sentenced on Christmas Day of 2009 to 11 years in prison for the “the crime of inciting subversion of state power”, nor has the Chinese communist party-state taken a single step toward democratisation or improving human rights during the year.1 This article offers a preliminary assessment of Charter 08, with special attention to its connection with liberal forces in China. Liu Xiaobo The Origins of Charter 08 and the Crystallisation of Liberal and Democratic Ideas in China Charter 08 was not a bolt from the blue but the result of careful deliberation and theoretical debate, especially the discourse on liberalism since the late 1990s. In its timing, Charter 08 anticipated that major political change would take place in China in 2009 in light of a number of important anniversaries. These included the 20th anniversary of the June 4th crackdown, the 50th anniversary of the exile of the Dalai Lama, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, and the 90th anniversary of the May 4th Movement. -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

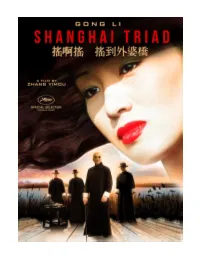

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao.