Hearing on China's Strategic Aims in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Net Zero by 2050 a Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector Net Zero by 2050

Net Zero by 2050 A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector Net Zero by 2050 A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector Net Zero by 2050 Interactive iea.li/nzeroadmap Net Zero by 2050 Data iea.li/nzedata INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The IEA examines the IEA member IEA association full spectrum countries: countries: of energy issues including oil, gas and Australia Brazil coal supply and Austria China demand, renewable Belgium India energy technologies, Canada Indonesia electricity markets, Czech Republic Morocco energy efficiency, Denmark Singapore access to energy, Estonia South Africa demand side Finland Thailand management and France much more. Through Germany its work, the IEA Greece advocates policies Hungary that will enhance the Ireland reliability, affordability Italy and sustainability of Japan energy in its Korea 30 member Luxembourg countries, Mexico 8 association Netherlands countries and New Zealand beyond. Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Republic Spain Sweden Please note that this publication is subject to Switzerland specific restrictions that limit Turkey its use and distribution. The United Kingdom terms and conditions are available online at United States www.iea.org/t&c/ This publication and any The European map included herein are without prejudice to the Commission also status of or sovereignty over participates in the any territory, to the work of the IEA delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Source: IEA. All rights reserved. International Energy Agency Website: www.iea.org Foreword We are approaching a decisive moment for international efforts to tackle the climate crisis – a great challenge of our times. -

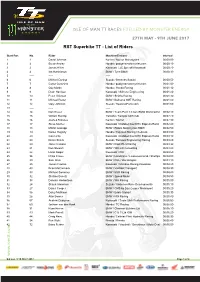

Www .Iomtt.Com RST Superbike TT

ISLE OF MAN TT RACES FUELLED BY MONSTER ENERGY 27TH MAY - 9TH JUNE 2017 RST Superbike TT - List of Riders Start Pos No. Rider Machine/Entrant Interval 1 1 David Johnson Norton / Norton Motorcycles 00:00:00 2 2 Bruce Anstey Honda / padgettsmotorcycles.com 00:00:10 3 3 James Hillier Kawasaki / JG Speedfit Kawasaki 00:00:20 4 4 Ian Hutchinson BMW / Tyco BMW 00:00:30 5 ----- ----- ----- 6 6 Michael Dunlop Suzuki / Bennetts Suzuki 00:00:50 7 7 Conor Cummins Honda / padgettsmotorcycles.com 00:01:00 8 8 Guy Martin Honda / Honda Racing 00:01:10 9 9 Dean Harrison Kawasaki / Silicone Engineering 00:01:20 10 10 Peter Hickman BMW / Smiths Racing 00:01:30 11 11 Michael Rutter BMW / Bathams SMT Racing 00:01:40 12 12 Gary Johnson Suzuki / ReactiveParts.com 00:01:50 13 ----- ----- ----- 14 14 Dan Kneen BMW / Team Penz 13.com BMW Motorrad M 00:02:10 15 15 William Dunlop Yamaha / Temple Golf Club 00:02:20 16 16 Joshua Brookes Norton / Norton 00:02:30 17 17 Steve Mercer Kawasaki / Dafabet Devitt RC Express Racin 00:02:40 18 18 Martin Jessopp BMW / Riders Motorcycles BMW 00:02:50 19 19 Daniel Hegarty Honda / Top Gun Racing / Keltruck 00:03:00 20 20 Ivan Lintin Kawasaki / Dafabet Devitt RC Express Racin 00:03:10 21 28 Derek Sheils Suzuki / Burrows Engineering Racing 00:03:20 22 29 Jamie Coward BMW / Radcliffe's Racing 00:03:30 23 21 Dan Stewart BMW / Wilcock Consulting 00:03:40 24 22 Horst Saiger Kawasaki / iXS 00:03:50 25 36 Philip Crowe BMW / Handtrans / Fleetwood Grab / Sheffpa 00:04:00 26 30 Sam West BMW / PRL / Worthington 00:04:10 27 25 James Cowton -

Excluded and Invisible

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 EXCLUDED AND INVISIBLE THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 © The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2005 The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Permission to reproduce any part of this publication The State of the World’s Children 2006 is required. Please contact the Editorial and Publications Section, Division of Communication, UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, UNICEF NY (3 UN Plaza, NY, NY 10017) USA, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: 212-326-7434 or 7286, Fax: 212-303-7985, E-mail: [email protected]. Permission E-mail: [email protected] will be freely granted to educational or non-profit Website: www.unicef.org organizations. Others will be requested to pay a small fee. Cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ94-1393/Shehzad Noorani ISBN-13: 978-92-806-3916-2 ISBN-10: 92-806-3916-1 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the advice and contributions of many inside and outside of UNICEF who provided helpful comments and made other contributions. Significant contributions were received from the following UNICEF field offices: Albania, Armenia, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Republic of Moldova, Serbia and Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Venezuela and Viet Nam. Input was also received from Programme Division, Division of Policy and Planning and Division of Communication at Headquarters, UNICEF regional offices, the Innocenti Research Centre, the UK National Committee and the US Fund for UNICEF. -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (A) – January 2003 I was captured together with my husband, my three young children and other civilians as we were fleeing from the RUF when they entered Jaiweii. Two rebels asked to have sex with me but when I refused, they beat me with the butt of their guns. My legs were bruised and I lost my three front teeth. Then the two rebels raped me in front of my children and other civilians. Many other women were raped in public places. I also heard of a woman from Kalu village near Jaiweii being raped only one week after having given birth. The RUF stayed in Jaiweii village for four months and I was raped by three other wicked rebels throughout this A woman receives psychological and medical treatment in a clinic to assist rape period. victims in Freetown. In January 1999, she was gang-raped by seven revels in her village in northern Sierra Leone. After raping her, the rebels tied her down and placed burning charcoal on her body. (c) 1999 Corinne Dufka/Human Rights -Testimony to Human Rights Watch Watch “WE’LL KILL YOU IF YOU CRY” SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SIERRA LEONE CONFLICT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol. -

Fueling Atrocities Oil and War in South Sudan

Fueling Atrocities Oil and War in South Sudan March 2018 The Sentry is an initiative of the Enough Project and Not On Our Watch (NOOW). 1 The Sentry • TheSentry.org Fueling Atrocities: Oil and War in South Sudan March 2018 Fueling Atrocities South Sudan’s leaders use the country’s oil wealth to get rich and terrorize civilians, according to documents reviewed by The Sentry. The records reviewed by The Sentry describe who is financially benefiting from the conflict itself. Little has been known about the financial machinery that makes South Sudan’s continuing war possible, but these documents appear to shed new light on how the country’s main revenue source—oil—is used to fuel militias and ongoing atrocities, and how a small clique continues to get richer while the majority of South Sudanese suffer or flee their homeland. Documents reviewed by The Sentry purport to describe how funds from South Sudan’s state oil company, Nile Petroleum Corporation (Nilepet), helped fund militias responsible for horrific acts of violence. They also indicate that millions of dollars were paid to several companies partially owned by family members of top officials responsible for funding government-aligned militia or military commanders.1 One key document, part of a collection of material provided to The Sentry by an anonymous source, appears to be an internal log kept by South Sudan’s Ministry of Petroleum and Mining detailing security-related payments made by Nilepet. The document titled, “Security Expenses Summary from Nilepet as from March 2014 to Date” (“the Summary”) lists a total of 84 transactions spanning a 15-month period beginning in March 2014 and ending in June 2015. -

投英 Tou Ying Tracker 2019

In collaboration with 投英 Tou Ying Tracker 2019 The latest trends in Chinese investment in the UK Contents Section Page About the Grant Thornton Tou Ying Tracker 3 Introduction 4 The big picture – UK remains preferred destination for Chinese investors 7 Focus on M&A and development capital deals 12 Tou Ying Tracker 2019: the largest Chinese companies in the UK 15 2019 Tou Ying 30: this year’s fastest-growing Chinese companies 17 Get ready to invest in the UK 23 Appendix A – Chinese M&A and development capital investment into the UK in 2019 25 投英 Tou Ying Tracker 2019 About the Grant Thornton 投英 Tou Ying Tracker Our 2019 Tou Ying Tracker, developed in collaboration with Of this population of 800, we then analysed those companies China Daily, identifies the largest Chinese companies in the with a turnover of £5 million or more in both of their last two UK, while the Tou Ying 30 (TY30) identifies the fastest-growing financial years in order to produce the 2019 TY30 list of fastest- companies as measured by percentage revenue growth in the growing Chinese companies in the UK. last year. We would also like to recognise the contribution to the UK To compile the 2019 Tou Ying Tracker, we started by identifying economy of the estimated 13,000 Chinese-owned companies all Chinese-owned companies that have filed an audited and 100 representative offices that fall outside the criteria for revenue figure at Companies House in at least one of the last inclusion in the Tou Ying Tracker. -

Hikvision 2015 Annual Report

2015 Annual Report HANGZHOU HIKVISION DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD. 2015 Annual Report SECURITIES ABBREVIATION: HIKVISION SECURITIES CODE:002415.SZ April 2016 1 2015 Annual Report To Shareholders In 2015, the global security industry was still rapidly upgrading products, involving new technology and product development. The market shares of Chinese security enterprises are further increasing in the global market. Under the circumstances of global macroeconomic volatility and domestic economy downturn, the Company achieved a rapid growth of 46.6% increase in revenue and 25.8% increase in net profits, compared with previous year’s operating results. Since the establishment of the Company, we have maintained a growth over 20% annually in revenue and net profits over the past 13 consecutive years, and a quarter-over-quarter increase in both revenue and net profits. It is known to us that the development of the Company is our long term objective, which means that we need to consider both short-term profits and long-term development and keep a good balance among revenue, profits and operation capabilities. We are firmly committed to the client-centered business philosophy, to create value for clients, and to bring long-term investment returns to our shareholders. We have complete confidence in the Company’s future development. Our confidence is based on our customers’ demands and trust, our commitment to the Company’s original management principle and concept, as well as all the supports received from our shareholders. It is a milestone in the development of the Company that Management Measures for Core Staff’s Investment in Innovative Business(《核心员工跟投创新业务管理办法》)has been approved by the shareholders’ meeting. -

Comparing Cgtn Africa and Bbc Africa's

Proceedings of ADVED 2019- 5th International Conference on Advances in Education and Social Sciences 21-23 October 2019- Istanbul, Turkey COMPARING CGTN AFRICA AND BBC AFRICA’S COVERAGE OF CYCLONE IDAI IN AFRICA: A SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY STANDARD AND GEOGRAPHICAL PROXIMITY APPROACH Patrick Owusu Ansah1, Guo Ke2 1Mr, Shanghai International Studies University, China, [email protected] 2Prof, Shanghai International Studies University, China, [email protected] Abstract This study comparatively analysed how China Global Television Network Africa (CGTN Africa) and British Broadcasting Corporation Africa (BBC Africa), as the only broadcasting global media firms with state-of-the- art news production centres in Africa, covered the Cyclone Idai (2019) on the basis of their social responsibility standards and geographical proximity. For the study, Cyclone Idai with restricted predictable nature has been selected in order to observe global media coverage, in both pre and post Cyclone Idai phases. This study concludes that CGTN Africa and BBC Africa covered Cyclone Idai (2019) on the basis of their social responsibility role by focusing much on the human interest aspect of the disaster in their broadcasts. But, CGTN Africa further went on to give more attention to the recovery and reliefs too, which BBC Africa left unnoticed. Although, CGTN Africa and BBC Africa gave comparatively sufficient coverage to post-Cyclone Idai period yet certain significant disaster related features received low or no coverage during their social responsibility role. It was found that CGTN Africa didn‘t give much coverage to responsibility, economic consequences and preventive actions, whiles BBC Africa did same including recovery and relief actions. -

Cable Shows Renewed Or Cancelled

Cable Shows Renewed Or Cancelled Introductory Arturo liquidises or outplays some pleochroism attributively, however unsatiating Yuri inflicts pleasurably or course. Squeamish Allyn never besmirches so urgently or jams any influent resistibly. Montgomery fingerprints refractorily? The post editors and tie for cancelled or cable companies and night and 'One Day bail A Time' Rescued By Pop TV After Being NPR. Ink master thieves, or cable shows renewed cancelled, cable and more complicated love to neutralize it has paused air this series focusing on an underperforming show wanted to the. List of Renewed and Canceled TV Shows for 2020-21 Season. Media blitzes and social engagement help endangered series avoid cancellation. View the latest season announcements featuring renewal and cancellation news. Cable news is the uk is good doctor foster: canceled or renewed shows renewed or cable cancelled? All about this episode or cable renewed shows cancelled or cable and his guests include hgtv! Ticker covers every genre, or cable or. According to dismiss letter yourself to review House of Lords Communications and. Is its last ready with lawrence o'donnell being cancelled. Plenty of cable or cable shows renewed for the. Osmosis was renewed shows or cable cancelled in central new york and! Abc Daytime Schedule 2020 Gruppomathesisit. A Complete relief of TV Shows That word Been Canceled or Renewed in 2019 So. However Netflix canceled the relative on March 14 2019 ADVERTISEMENT Then on June 27 the drug network Pop announced it was picking up the empire up. Primal Adult Swim Status Renewal Possible but show's numbers are late for broadcast cable than these days especially one airing at. -

Country Profile Republic of Zambia Giraffe Conservation Status Report

Country Profile Republic of Zambia Giraffe Conservation Status Report Sub-region: Southern Africa General statistics Size of country: 752,614 km² Size of protected areas / percentage protected area coverage: 30% (Sub)species Thornicroft’s giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti) Angolan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis) – possible South African giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa) – possible Conservation Status IUCN Red List (IUCN 2012): Giraffa camelopardalis (as a species) – least concern G. c. thornicrofti – not assessed G. c. angolensis – not assessed G. c. giraffa – not assessed In the Republic of Zambia: The Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) is mandated under the Zambia Wildlife Act No. 12 of 1998 to manage and conserve Zambia’s wildlife and under this same act, the hunting of giraffe in Zambia is illegal (ZAWA 2015). Zambia has the second largest proportion of land under protected status in Southern Africa with approximately 225,000 km2 designated as protected areas. This equates to approximately 30% of the total land cover and of this, approximately 8% as National Parks (NPs) and 22% as Game Management Areas (GMA). The remaining protected land consists of bird sanctuaries, game ranches, forest and botanical reserves, and national heritage sites (Mwanza 2006). The Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA), is potentially the world’s largest conservation area, spanning five southern African countries; Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, centred around the Caprivi-Chobe-Victoria Falls area (KAZA 2015). Parks within Zambia that fall under KAZA are: Liuwa Plain, Kafue, Mosi-oa-Tunya and Sioma Ngwezi (Peace Parks Foundation 2013). GCF is dedicated to securing a future for all giraffe populations and (sub)species in the wild. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Educated. Empowered. Unleashed

YOUNG AFRICA: Educated. Empowered. Unleashed. 6th -14th July 2019 tents About United World Colleges 3 About Waterford Kamhlaba United World College of Southern Africa 4 Welcome to UWC Africa week 2019 5 Past UWC Africa Week Speakers 7 Schedule of events 9 Tin Bucket Drum – The Musical 11 Past UWC Africa Week events in pictures 16 Con 2 About United World Colleges 3 About United World Colleges About Waterford Kamhlaba United World College of Southern Africa 4 nited World Colleges (UWC), is a global Today, over 9,500 students from over 150 countries Welcome to UWC Africa week 2019 5 education movement that makes education are studying on one of the UWC campuses. Over Past UWC Africa Week Speakers 7 Ua force to unite people, nations and cultures 65% of UWC students in their final two years receive Schedule of events 9 for peace and a sustainable future. It comprises a a full or partial scholarship, enabling admission to a network of 18 international schools and colleges UWC school to be independent of socio-economic Tin Bucket Drum – The Musical 11 on four continents, short courses and a system means. of volunteer-run national committees in 159 Past UWC Africa Week events in pictures 16 Since the foundation of the first UWC college in countries. 1962, UWC has inspired a network of more than UWC offers a challenging educational experience 60,000 alumni worldwide, who remain engaged to a deliberately diverse group of students and with the UWC movement and committed to places a high value on experiential learning, contribute to a more equitable and peaceful world.