Increasing Visibility of Lesbian Desire in Chinese Cinemas By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun's Work

Chinese National Revitalization and Social Darwinism in Lu Xun’s Work By Yuanhai Zhu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Literature University of Alberta ©Yuanhai Zhu, 2015 ii Abstract This thesis explores decolonizing nationalism in early 20th century China through its literary embodiment. The topic in the thesis is Lu Xun, a canonical modern Chinese realist whose work is usually and widely discussed in scholarly works on Chinese literature and Chinese history in this period. Meanwhile, late 19th century and early 20th century, as the only semi-post-colonial period in China, has been investigated by many scholars via the theoretical lens of post-colonialism. The intellectual experience in China during this period is usually featured by the encounters between Eastern and Western intellectual worlds, the translation and appropriation of Western texts in the domestic Chinese intellectual world. In this view, Lu Xun’s work is often explored through his individualism which is in debt to Nietzsche, as well as other western romanticists and existentialists. My research purpose is to reinvestigate several central topics in Lu Xun’s thought, like the diagnosis of the Chinese national character, the post-colonial trauma, the appropriation of Nietzsche and the critique of imperialism and colonization. These factors are intertwined with each other in Lu Xun’s work and embody the historical situation in which the Chinese decolonizing nationalism is being bred and developed. Furthermore, by showing how Lu Xun’s appropriation of Nietzsche falls short of but also challenges its original purport, the thesis demonstrates the critique of imperialism that Chinese decolonizing nationalism initiates, as well as the aftermath which it brings to modern China. -

Bad Blood, Good Movie? Laurie Kelley and Paul Clement a Viewer’S Guide: New Documentary About Hemophilia HIV History

PEN 11-10 CL_PEN 11/16/10 6:27 AM Page 1 Parent Empowerment Newsletter LA Kelley Communications, Inc. inside 3 As I See It: The Hemophilia Archive 4 Inhibitor Insights: Inhibitor Products 5 Transitions: Living Abroad with Peace of Mind 6 Richard’s Review: Hemophilia and AIDS in Film Bad Blood, Good Movie? Laurie Kelley and Paul Clement A Viewer’s Guide: New Documentary about Hemophilia HIV History A new film about hemophilia during the HIV crisis of the 1980s has energized our community. Bad Blood documents events that caused the mass contamination of factor products. Community advocates cheer the movie’s release and hope it will bring more attention to the hemophilia community—for funds, for continued blood safety, and for preserving memories of our fallen heroes. But will Bad Blood needlessly raise fears about plasma- derived products? Most Americans with hemophilia use recombinant products, and most don’t fully understand the difference between product safety and purity. Many of us aren’t aware of the complex production of products, or the fact that all US products are now considered safe. Use of plasma-derived products is on the rise as a treatment for inhibitors—and parents are worried. Now, along comes a film that taps into a parent’s deepest fear: what am I injecting into my child? Will this new documentary reinforce that fear, preventing parents from making good product choices? Flashback It was November 2008, the opening event of National Hemophilia Foundation’s annual meeting in Denver. The audience of hemophilia families and hemophilia chapter representatives filed into a large, festive room decorated with red and blue balloons. -

Rainie Yang Ambiguous Download

Rainie yang ambiguous download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Las letras y el video de la canción Ambiguous de Rainie Yang: Ambiguous make people become greedy until waiting lost its means pity that me and you could not write out an renuzap.podarokideal.ru://renuzap.podarokideal.ru · Clip de Rainie Yang sur Ambiguous Pour le Drama "Devil Beside You" avec Mike He Jun Xiangrenuzap.podarokideal.ru Yesterday was Taiwanese actress-singer Rainie Yang’s 31st birthday and she posted a youthful-looking selfie on Weibo of herself with the peace sign. Her rumoured boyfriend, Chinese singer-songwriter Li Ronghao, posted an ambiguous birthday wish on Weibo yesterday morning without saying to whom the blessing was meant for, causing fans to renuzap.podarokideal.ru Ambiguous by Rainie Yang. Ambiguous let people feel wronged. Could not find the evidence of loving each other. When should go forward, when should give up. Even do not have courage to hug. Ambiguous make people become greedy. Until waiting lost its means. Pity renuzap.podarokideal.ru download it here at sugarpain_music the post will be public for 48 hours [: join to see more posts Yang began her career as a member of the all-girl singing group 4 in Love, where she was given the stage name of renuzap.podarokideal.ru://renuzap.podarokideal.ru Rainie Yang - Listen to Rainie Yang on Deezer. With music streaming on Deezer you can discover more than 56 million tracks, create your own playlists, and share your favourite tracks with your renuzap.podarokideal.ru://renuzap.podarokideal.ru Rainie Yang (traditional Chinese: 楊丞琳; simplified Chinese: 杨丞琳; pinyin: Yáng Chénglín; born June 4, in Taipei, Taiwan) is a popular Chinese singer, actress, and talk show host. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

Teaching Post-Mao China Not Connected

RESOURCES FILM REVIEW ESSAY documentary style with which filmmaker Zhang Yimou is normally Teaching Post-Mao China not connected. This style—long shots of city scenes filled with people Two Classic Films and a subdued color palette—contribute to the viewer’s understand - ing of life in China in the early 1990s. The village scenes could be By Melisa Holden from anytime in twentieth century China, as the extent of moderniza - tion is limited. For example, inside peasants’ homes, viewers see Introduction steam spewing from characters’ mouths because of the severe cold The Story of Qiu Ju and Beijing Bicycle are two films that have been and lack of central heating. However, when Qiu Ju travels to the ur - used in classrooms since they were produced (1992 and 2001, respec - banized areas, it becomes obvious that the setting is the late twentieth tively). Today, these films are still relevant to high school and under - century. The film was shot only a couple of years after the Tiananmen graduate students studying history, literature, and related courses Square massacre in 1989. Zhang’s previous two films ( Ju Dou and about China, as they offer a picture of the grand scale of societal Raise the Red Lantern ) had been banned in China, but with The Story change that has happened in China in recent decades. Both films il - of Qiu Ju , Zhang depicts government officials in a positive light, lustrate contemporary China and the dichotomy between urban and therefore earning the Chinese government’s endorsement. One feels rural life there. The human issues presented transcend cultural an underlying tension through Qiu Ju’s search for justice, as if it is not boundaries and, in the case of Beijing Bicycle , feature young charac - only justice for her husband’s injured body and psyche, but also jus - ters that are the age of US students, allowing them to further relate to tice supposedly found through democracy. -

TAIWAN BIENNIAL FILM FESTIVAL 2019 FILM INFORMATION/TIMELINE October 18, 2019 7:30 Pm

TAIWAN BIENNIAL FILM FESTIVAL 2019 FILM INFORMATION/TIMELINE October 18, 2019 7:30 pm – Opening Film HEAVY CRAVING Billy Wilder Theater In a special celebration, UCLA Film & Television Archive and Taiwan Academy in Los Angeles are excited to accompany the North American premiere of the film with a guest appearance by the film’s acclaimed Director/Screenwriter Hsieh Pei-ju, who will participate in a post-screening Q&A. HEAVY CRAVING (2019) Synopsis: a talented chef for a preschool run by her demanding mother, Ying-juan earns praise for her culinary creations but scorn for her weight. Even the children she feeds have dubbed her “Ms. Dinosaur” for her size. Joining a popular weight loss program seems like an answer but it’s the unlikely allies she finds outside the program—and the obstacles she faces in it—that help her find a truer path to happiness. Writer-director Hsieh Pei-ju doesn’t shy away from the darker sides of self-discovery in what ultimately proves a rousing feature debut, winner of the Audience’s Choice award at this year’s Taipei Film Festival. Director/Screenwriter: Hsieh Pei-ju. Cast: Tsai Jia-yin, Yao Chang, Samantha Ko. October 19, 2019 3:00 pm – “Focus on Taiwan” Panel Billy Wilder Theater Admission: Free With the ‘Focus on Taiwan’ panel UCLA Film & Television Archive and Taiwan Academy in Los Angeles are thrilled to present a curated afternoon of timely conversations about issues facing the Taiwan film industry at home and abroad, including gender equality and inclusion of women and the LGBTQ community on screen and behind the camera, the challenges of marketing Taiwanese productions internationally and more. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

Perspectives in Flux

Perspectives in Flux Red Sorghum and Ju Dou's Reception as a Reflection of the Times Paisley Singh Professor Smith 2/28/2013 East Asian Studies Thesis Seminar Singh 1 Abstract With historical and critical approach, this thesis examined how the general Chinese reception of director Zhang Yimou’s Red Sorghum and Ju Dou is reflective of the social conditions at the time of these films’ release. Both films hold very similar diegeses and as such, each generated similar forms of filmic interpretation within the academic world. Film scholars such as Rey Chow and Sheldon Lu have critiqued these films as especially critical of female marginalization and the Oedipus complex present within Chinese society. Additionally, the national allegorical framing of both films, a common pattern within Chinese literary and filmic traditions, has thoroughly been explored within the Chinese film discipline. Furthermore, both films have been subjected to accusations of Self-Orientalization and Occidentalism. The similarity between both films is undeniable and therefore comparable in reference to the social conditions present in China and the changing structures within the Chinese film industry during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although Red Sorghum and Ju Dou are analogous, each received almost opposite reception from the general Chinese public. China's social and economic reform, film censorship, as well as the government’s intervention and regulation of the Chinese film industry had a heavy impact upon each film’s reception. Equally important is the incidence of specific events such as the implementation of the Open Door policy in the 1980s and 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. -

Foreignizing Translation on Chinese Traditional Funeral Culture in the Film Ju Dou

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 15, No. 1, 2017, pp. 47-50 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/9758 www.cscanada.org Foreignizing Translation on Chinese Traditional Funeral Culture in the Film Ju Dou PENG Xiamei[a],*; WANG Piaodi[a] [a]School of Foreign Languages, North China Electric Power University, Since Red Sorghum, the first film directed by him has Beijing, China. won the Golden Bear on February 23th, 1988, Zhang and *Corresponding author. his films produced a series of surprises for the Chinese Supported by The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central people and the world (Ban, 2003). He was said to be one Universities (JB2017074). of the most advanced figures in Chinese movies, and his films are regarded as a symbol of Chinese contemporary Received 15 April 2017; accepted 17 July 2017 culture. Published online 26 July 2017 In Zhang’s films, you’ll see a profound understanding of Chinese traditional feudal consciousness and strong Abstract critical spirit, which proves to be a strong sense of China is a country with more than five thousand years of history and life consciousness. It’s a peculiar landscape traditional cultures, which is broad and profound. With the of traditional folk customs and also praises for women’s increasing international status of China in recent years, rebellious spirit. The constant exploration and innovation more and more countries are interested in China and its in the film style and language represent the rise of a traditional culture as well. Film and television works, as new film trend. -

La Sociedad China a Través De Su Cine

E.G~oooo OCIOO 1'11 ~ ,qq~ ~ QC4 (j) 1q~t Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Campus Eugenio Garza Sada La sociedad china a través de su cine Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de Maestro en Educación con especialidad en Humanidades Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán Asesor: Dr. Víctor López Villafañe Monterrey, N.L. abril de 1997 INTITUTO TECNOLOGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY CAMPUS EUGENIO GARZA SADA La sociedad china a través de su cine Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de Maestro en Educación con especialidad en Humanidades Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán Asesor: Dr. Victor López Villafañe Monterrey, N.L. abril de 1997. A Martha, Alberto y Viridiana, por el tiempo robado. i Reconocimientos Al Dr. Victor López Villafañe, por el interés en este trabajo y por las palabras de aliento. Al ITESM Campus Sinaloa, por el apoyo nunca regateado. i i Resumen Tesis: "El cine chino a través de su cine". Autor: Ernesto Diez-Martínez Guzmán. Asesor: Dr. Víctor López Villafañe. La presente investigación. llamada "La sociedad china a través de su cine", pretende arribar al conocimiento de los mecanismos sociales, culturales y de poder de la sociedad china en el siglo XX, todo ello a través del estudio de la cinematografía del país más poblado del mundo. Desde los albores de la industria hasta la inminente fusión de Hong Kong con la China continental, el cine ha sido un importantísimo medio cultural, de entretenimiento y de propaganda, que ha sido testigo y actor fundamental de las grandes transformaciones de este país. -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

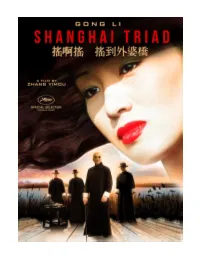

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao.