The Rocky Path from Elections to a New Constitution in Tunisia: Mechanisms for Consensus-Building and Inclusive Decision-Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ennahda's Approach to Tunisia's Constitution

BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER ANALYSIS PAPER Number 10, February 2014 CONVINCE, COERCE, OR COMPROMISE? ENNAHDA’S APPROACH TO TUNISIA’S CONSTITUTION MONICA L. MARKS B ROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high- quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its scholars. Copyright © 2014 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha TABLE OF C ONN T E T S I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 III. Diverging Assessments .................................................................................................4 IV. Ennahda as an “Army?” ..............................................................................................8 V. Ennahda’s Introspection .................................................................................................11 VI. Challenges of Transition ................................................................................................13 -

![[Tunisia, 2013-2015] Tunisia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9980/tunisia-2013-2015-tunisia-349980.webp)

[Tunisia, 2013-2015] Tunisia

Case Study Series Women in Peace & Transition Processes: [Tunisia, 2013-2015] December 2019 Name of process Tunisia Constituent Assembly (2013-2015) and National Dialogue Type of process Constitution-making The role of women in resolving Tunisia’s post-“Arab Spring” political crisis, which and political reform peaked in 2013, was limited, but not insignificant. Institutionalized influence Modality of women's was very limited: there was no formal inclusion of women’s groups in the main inclusion: negotiations of the 2013/2014 National Dialogue and the influence of organized • Consultations advocacy was also limited in the pre-negotiation and implementation phases. • Inclusive commission For example, the women’s caucus formed in the Tunisian National Constituent • Mass mobilization Assembly (Tunisia’s Parliament from the end of 2011 to 2014, hereafter NCA) Women’s influence could not prevail over party politics and was not institutionalized. However, in the process: individual women played decisive roles in all three phases: one of the four main Moderate influence due to: civil society mediators, who not only facilitated the main negotiations, but also • + The progressive legislation in initiated the dialogue process and held consultations to determine the agenda Tunisia on women's rights and in the pre-negotiation phase, was a woman, (Ouided Bouchamaoui President political participation of the Tunisian Union of Industry, Commerce and Crafts (UTICA), from 2011 • + The influential role and status to 2018). A small number of women represented political parties in the of individual women negotiations of the National Dialogue. And women were active in consultations • - The lack of organized and group-specific women's and commissions concerning the National Dialogue, before, in parallel or after involvement the main negotiation period, for example in the consensus committee of the • - The involvement of relatively National Constituent Assembly. -

Forming the New Tunisian Government

Viewpoints No. 71 Forming the New Tunisian Government: “Relative Majority” and the Reality Principle Lilia Labidi Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center and former Minister for Women’s Affairs, Tunisia February 2015 After peaceful legislative and presidential elections in Tunisia toward the end of 2014, which were lauded on both the national and international levels, the attempt to form a new government reveals the tensions among the various political forces and the difficulties of constructing a democratic system in the country that was the birthplace of the "Arab Spring." Middle East Program 0 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ On January 23, 2015, Prime Minister Habib Essid announced the members of the new Tunisian government after much negotiation with the various political parties. Did Prime Minister Essid intend to give a political lesson to Tunisians, both to those who had been elected to the Assembly of the People’s Representatives (ARP) and to civil society? The ARP’s situation is worrisome for two reasons. First, 76 percent of the groups in political parties elected to the ARP have not submitted the required financial documents to the appropriate authorities in a timely manner. They therefore run the risk of losing their seats. Second, ARP members are debating the rules and regulations of the parliament as well as the definition of parliamentary opposition. They have been unable to reach an agreement on this last issue; without an agreement, the ARP is unable to vote on approval for a proposed government. There is conflict within a number of political parties in this context. In Nidaa Tounes, some members of the party, including MP Abdelaziz Kotti, have argued that there has been no exchange of information within the party regarding the formation of the government. -

Ansar Al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST)

Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) Name: Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) Type of Organization: Insurgent non-state actor religious social services provider terrorist transnational violent Ideologies and Affiliations: ISIS–affiliated group Islamist jihadist Qutbist Salafist Sunni takfiri Place of Origin: Tunisia Year of Origin: 2011 Founder(s): Seifallah Ben Hassine Places of Operation: Tunisia Overview Also Known As: Al-Qayrawan Media Foundation1 Partisans of Sharia in Tunisia7 Ansar al-Sharia2 Shabab al-Tawhid (ST)8 Ansar al-Shari’ah3 Supporters of Islamic Law9 Ansar al-Shari’a in Tunisia (AAS-T)4 Supporters of Islamic Law in Tunisia10 Ansar al-Shari’ah in Tunisia5 Supporters of Sharia in Tunisia11 Partisans of Islamic Law in Tunisia6 Executive Summary: Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) was a Salafist group that was prominent in Tunisia from 2011 to 2013.12 AST sought to implement sharia (Islamic law) in the country and used violence in furtherance of that goal under the banner of hisbah (the duty to command moral acts and prohibit immoral ones).13 AST also actively engaged in dawa (Islamic missionary work), which took on many forms but were largely centered upon Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) the provision of public services.14 Accordingly, AST found a receptive audience among Tunisians frustrated with the political instability and dire economic conditions that followed the 2011 Tunisian Revolution.15 The group received logistical support from al-Qaeda central, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL), and later, from ISIS.16 AST was designated as a terrorist group by the United States, the United Nations, and Tunisia, among others.17 AST was originally conceived in a Tunisian prison by 20 Islamist inmates in 2006, according to Aaron Zelin at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. -

Tunisia on Razor's Edge After Assassination of Chokri Belaid

Summary: The assassination of leftist leader Chokri Belaid on February 6, apparently by Islamists, has brought into the open the long-simmering conflict that has pitted the ruling Islamist Ennahda Party against leftists, trade unionists, and secularists, who have staged the first general strike in 40 years and the largest street demonstrations since the 2011 revolution - - Editors Tunisia on Razor’s Edge after Assassination of Chokri Belaid Kevin Anderson February 13, 2013 February 6, a Day of Infamy The cowardly assassination of Chokri Belaid has thrown Tunisia into its biggest crisis since the overthrow of the Ben Ali regime in 2011. Gunned down as he left his home on the morning of February 6, apparently by Islamist militants, Belaid was one of the country’s most famous labor lawyers and leftist leaders. Known for having defended the Gafsa phosphate miners against state repression after their 2008 strike under the old regime, Belaid had been a prominent member of the secular left for decades. He was a lifelong Marxist who was a leading figure in the Popular Front, founded last summer as a potentially large grouping of leftist and secular forces. Having already served time under the old regime, Belaid was not intimidated by the death threats he constantly received from Islamists, with some imams openly calling for his assassination in their sermons. Within hours of Belaid’s death, crowds of youths gathered to protest in the center of Tunis outside the Interior (Police) Ministry, calling for the government to resign. The response was less verbal but more direct among the working classes. -

Tunisian Human Rights League Report on the Freedom Of

Tunisian Human Rights League The Press: A Disaster Victim Report on the Freedom of Information in Tunisia May 2003 PREAMBLE On the occasion of the international day of the press freedom, the Tunisian League for the Human Rights Defence puts at the hand of the public opinion this report about information and press freedom in Tunisia after it issued in 1999 under the title of “Press freedom in Tunisia” a complete study relevant to the press reality in Tunisia. The League insisted in its report, articles and activities on its interest in the press reality In Tunisia because this area knew a serious decline during the last years, which let the Tunisian citizens abandon it and appeal to the foreign press, since the Union is aware that the press is the reflective mirror of any progress that the country is likely to record and since It also realized that the freedom of expression is the way to issue general freedoms. This report focused on clinging to the recorded events and happenings that the last century had known and which show by themselves the decline that this field has known through hamper and pressure on journalists as well as the excessive similitude made between all mass media, which led to a national agreement about requiring the improvement of this field. This report is not limited to the various harms which affected the journalists and newspapers resulting from the authority control, but this report concerns every citizen who tries to put his rights of expression into practice mainly through the internet, but who also faced arrest and trial. -

Islam and Politics in Tunisia

Islam and Politics in Tunisia How did the Islamist party Ennahda respond to the rise of Salafism in post-Arab Spring Tunisia and what are possible ex- planatory factors of this reaction? April 2014 Islam and Politics in a Changing Middle East Stéphane Lacroix Rebecca Koch Paris School of© International Affairs M.A. International Security Student ID: 100057683 [email protected] Words: 4,470 © The copyright of this paper remains the property of its author. No part of the content may be repreoduced, published, distributed, copied or stored for public use without written permission of the author. All authorisation requests should be sent to [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 2. Definitions and Theoretical Framework ............................................................... 4 3. Analysis: Ennahda and the Tunisian Salafi movements ...................................... 7 3.1 Ennahda ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Salafism in Tunisia ....................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Reactions of Ennahda to Salafism ................................................................................ 8 4. Discussion ................................................................................................................ 11 5. Conclusion -

Tunisia: Freedom of Expression Under Siege

Tunisia: Freedom of Expression under Siege Report of the IFEX Tunisia Monitoring Group on the conditions for participation in the World Summit on the Information Society, to be held in Tunis, November 2005 February 2005 Tunisia: Freedom of Expression under Siege CONTENTS: Executive Summary p. 3 A. Background and Context p. 6 B. Facts on the Ground 1. Prisoners of opinion p. 17 2. Internet blocking p. 21 3. Censorship of books p. 25 4. Independent organisations p. 30 5. Activists and dissidents p. 37 6. Broadcast pluralism p. 41 7. Press content p. 43 8. Torture p. 46 C. Conclusions and Recommendations p. 49 Annex 1 – Open Letter to Kofi Annan p. 52 Annex 2 – List of blocked websites p. 54 Annex 3 – List of banned books p. 56 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) is a global network of 64 national, regional and international freedom of expression organisations. This report is based on a fact-finding mission to Tunisia undertaken from 14 to 19 January 2005 by members of the IFEX Tunisia Monitoring Group (IFEX-TMG) together with additional background research and Internet testing. The mission was composed of the Egyptian Organization of Human Rights, International PEN Writers in Prison Committee, International Publishers Association, Norwegian PEN, World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters (AMARC) and World Press Freedom Committee. Other members of IFEX-TMG are: ARTICLE 19, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE), the Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Studies (CEHURDES), Index on Censorship, Journalistes en Danger (JED), Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA), and World Association of Newspapers (WAN). -

Re-Thinking Secularism in Post-Independence Tunisia

The Journal of North African Studies ISSN: 1362-9387 (Print) 1743-9345 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fnas20 Re-thinking secularism in post-independence Tunisia Rory McCarthy To cite this article: Rory McCarthy (2014) Re-thinking secularism in post-independence Tunisia, The Journal of North African Studies, 19:5, 733-750, DOI: 10.1080/13629387.2014.917585 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.917585 Published online: 12 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 465 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fnas20 Download by: [Rory McCarthy] Date: 15 December 2015, At: 02:37 The Journal of North African Studies, 2014 Vol. 19, No. 5, 733–750, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.917585 Re-thinking secularism in post- independence Tunisia Rory McCarthy* St Antony’s College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK The victory of a Tunisian Islamist party in the elections of October 2011 seems a paradox for a country long considered the most secular in the Arab world and raises questions about the nature and limited reach of secularist policies imposed by the state since independence. Drawing on a definition of secularism as a process of defining, managing, and intervening in religious life by the state, this paper identifies how under Habib Bourguiba and Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali the state sought to subordinate religion and to claim the sole right to interpret Islam for the public in an effort to win the monopoly over religious symbolism and, with it, political control. -

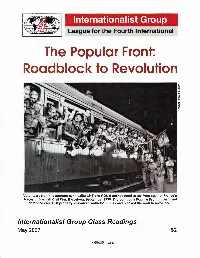

The Popular Front: Roadblock to Revolution

Internationalist Group League for th,e Fourth International The Popular Front: Roadblock to Revolution Volunteers from the anarcho-syndicalist CNT and POUM militias head to the front against Franco's forces in Spanish Civil War, Barcelona, September 1936. The bourgeois Popular Front government defended capitalist property, dissolved workers' militias and blocked the road to revolution. Internationalist Group Class Readings May 2007 $2 ® <f$l~ 1162-M Introduction The question of the popular front is one of the defining issues in our epoch that sharply counterpose the revolution ary Marxism of Leon Trotsky to the opportunist maneuverings of the Stalinists and social democrats. Consequently, study of the popular front is indispensable for all those who seek to play a role in sweeping away capitalism - a system that has brought with it untold poverty, racial, ethnic, national and sexual oppression and endless war - and opening the road to a socialist future. "In sum, the People's Front is a bloc of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat," Trotsky wrote in December 1937 in re sponse to questions from the French magazine Marianne. Trotsky noted: "When two forces tend in opposite directions, the diagonal of the parallelogram approaches zero. This is exactly the graphic formula of a People's Front govern ment." As a bloc, a political coalition, the popular (or people's) front is not merely a matter of policy, but of organization. Opportunists regularly pursue class-collaborationist policies, tailing after one or another bourgeois or petty-bourgeois force. But it is in moments of crisis or acute struggle that they find it necessary to organizationally chain the working class and other oppressed groups to the class enemy (or a sector of it). -

Ambigouos Endings: Middle East Regional Security in the Wake Of

DIIS REPORT 2011:03 DIIS REPORT AMBIGUOUS ENDINGS MIDDLE EAST REGIONAL SECURITY IN THE WAKE OF THE ARAB UPRISINGS AND THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR Helle Malmvig DIIS REPORT 2013:23 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2013:23 © Copenhagen 2013, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: © Polfoto / Karam Alhamad Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-601-8 (print) ISBN 978-87-7605-602-5 (pdf ) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk This publication is part of DIIS’s Defence and Security Studies project which is funded by a grant from the Danish Ministry of Defence Helle Malmvig, Senior Researcher [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2013:23 Contents Executive Summary in Danish 4 Executive summary 5 1. Introduction, aim and structure 7 2. Middle East regional security from 2001 to 2010 9 3. The Arab Uprisings and regional order 2011- 14 3.1 Changing state-society dynamics 14 3.2 Neither ally nor enemy: the weakening of foreign policy posturing and the pro- anti-Western divide 17 3.3 The weakening of the resistance front and the conservative-radical divide 20 3.4 Into the fray: the Sunni-Shia rift 23 3.5 The end of pragmatist foreign policy and the emergence of a Salafi-Muslim Brotherhood divide 26 4. -

The Bahrain Situation

(Doha Institute) Assessment Report The Bahrain Situation Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies Assessment Report Doha, March - 2011 Assessment Report Copyrights reserved for Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies © 2011 Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies The Bahrain Situation Against the backdrop of worsening social and political conditions, issues and a protracted tradition of political opposition in Bahrain, the revolutions of Egypt and Tunisia have driven young people in this country to emulate the new model of Arab protest. The slogans raised in these protests (February 14) express the demands for national constitutional reform in accordance with 2001 National Action Charter, and the lifting of the security apparatus restrictions on freedoms in the country. As was the case in Egypt, these youth are largely unaffiliated to any of the political currents, they have communicated with one another via the internet, and are composed of both Shiites and Sunnis in equal measure. They have expressed their desire to form a leadership body representing Sunni and Shiite citizens, but their aversion to sectarian quotas characterizing Lebanon and Iraq has made these youth reluctant on this front, preferring to defer to election results to determine the composition of the leadership. Also notable is the strong participation of women. Shiite opposition movements have shown themselves to be powerful and organized political forces in the popular and democratic mobilizations. The opposition currents in the country — what are commonly known as the “seven organizations” (al-Wifaq, Wa’d, al-Minbar al- Taqaddumi [Democratic Progressive Tribune], al-Amal al-Islami [“Amal”], al-Tajammu al- Qawmi [Nationalist Democratic Assembly], al-Tajammu al-Watani [National Democratic Assemblage], and al-Ikha) — had joined the protest movements from the outset.