Ungarn Jahrbuch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Wake of the Compendia Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures

In the Wake of the Compendia Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures Edited by Markus Asper Philip van der Eijk Markham J. Geller Heinrich von Staden Liba Taub Volume 3 In the Wake of the Compendia Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia Edited by J. Cale Johnson DE GRUYTER ISBN 978-1-5015-1076-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-5015-0250-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0252-1 ISSN 2194-976X Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Typesetting: Meta Systems Publishing & Printservices GmbH, Wustermark Printing and binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Notes on Contributors Florentina Badalanova Geller is Professor at the Topoi Excellence Cluster at the Freie Universität Berlin. She previously taught at the University of Sofia and University College London, and is currently on secondment from the Royal Anthropological Institute (London). She has published numerous papers and is also the author of ‘The Bible in the Making’ in Imagining Creation (2008), Qurʾān in Vernacular: Folk Islam in the Balkans (2008), and 2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch: Text and Context (2010). Siam Bhayro was appointed Senior Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies in the Department of Theology and Religion, University of Exeter, in 2012, having previously been Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies since 2007. -

Caterina Corner in Venetian History and Iconography Holly Hurlburt

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2009, vol. 4 Body of Empire: Caterina Corner in Venetian History and Iconography Holly Hurlburt n 1578, a committee of government officials and monk and historian IGirolamo Bardi planned a program of redecoration for the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Great Council Hall) and the adjoining Scrutinio, among the largest and most important rooms in the Venetian Doge’s Palace. Completed, the schema would recount Venetian history in terms of its international stature, its victories, and particularly its conquests; by the sixteenth century Venice had created a sizable maritime empire that stretched across the eastern Mediterranean, to which it added considerable holdings on the Italian mainland.1 Yet what many Venetians regarded as the jewel of its empire, the island of Cyprus, was calamitously lost to the Ottoman Turks in 1571, three years before the first of two fires that would necessitate the redecoration of these civic spaces.2 Anxiety about such a loss, fear of future threats, concern for Venice’s place in evolving geopolitics, and nostalgia for the past prompted the creation of this triumphant pro- gram, which featured thirty-five historical scenes on the walls surmounted by a chronological series of ducal portraits. Complementing these were twenty-one large narratives on the ceiling, flanked by smaller depictions of the city’s feats spanning the previous seven hundred years. The program culminated in the Maggior Consiglio, with Tintoretto’s massive Paradise on one wall and, on the ceiling, three depictions of allegorical Venice in triumph by Tintoretto, Veronese, and Palma il Giovane. These rooms, a center of republican authority, became a showcase for the skills of these and other artists, whose history paintings in particular underscore the deeds of men: clothed, in armor, partially nude, frontal and foreshortened, 61 62 EMWJ 2009, vol. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

Manuel II Palaiologos' Point of View

The Hidden Secrets: Late Byzantium in the Western and Polish Context Małgorzata Dąbrowska The Hidden Secrets: Late Byzantium in the Western and Polish Context Małgorzata Dąbrowska − University of Łódź, Faculty of Philosophy and History Department of Medieval History, 90-219 Łódź, 27a Kamińskiego St. REVIEWERS Maciej Salamon, Jerzy Strzelczyk INITIATING EDITOR Iwona Gos PUBLISHING EDITOR-PROOFREADER Tomasz Fisiak NATIVE SPEAKERS Kevin Magee, François Nachin TECHNICAL EDITOR Leonora Wojciechowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Katarzyna Turkowska Cover Image: Last_Judgment_by_F.Kavertzas_(1640-41) commons.wikimedia.org Printed directly from camera-ready materials provided to the Łódź University Press This publication is not for sale © Copyright by Małgorzata Dąbrowska, Łódź 2017 © Copyright for this edition by Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź 2017 Published by Łódź University Press First edition. W.07385.16.0.M ISBN 978-83-8088-091-7 e-ISBN 978-83-8088-092-4 Printing sheets 20.0 Łódź University Press 90-131 Łódź, 8 Lindleya St. www.wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl e-mail: [email protected] tel. (42) 665 58 63 CONTENTS Preface 7 Acknowledgements 9 CHAPTER ONE The Palaiologoi Themselves and Their Western Connections L’attitude probyzantine de Saint Louis et les opinions des sources françaises concernant cette question 15 Is There any Room on the Bosporus for a Latin Lady? 37 Byzantine Empresses’ Mediations in the Feud between the Palaiologoi (13th–15th Centuries) 53 Family Ethos at the Imperial Court of the Palaiologos in the Light of the Testimony by Theodore of Montferrat 69 Ought One to Marry? Manuel II Palaiologos’ Point of View 81 Sophia of Montferrat or the History of One Face 99 “Vasilissa, ergo gaude...” Cleopa Malatesta’s Byzantine CV 123 Hellenism at the Court of the Despots of Mistra in the First Half of the 15th Century 135 4 • 5 The Power of Virtue. -

Redalyc.CRUSADING and MATRIMONY in the DYNASTIC

Byzantion Nea Hellás ISSN: 0716-2138 [email protected] Universidad de Chile Chile BARKER, JOHN W. CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY Byzantion Nea Hellás, núm. 36, 2017, pp. 157-183 Universidad de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=363855434009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BYZANTION NEA HELLÁS Nº 36 - 2017: 157 / 183 CRUSADING AND MATRIMONY IN THE DYNASTIC POLICIES OF MONTFERRAT AND SAVOY JOHN W. BARKER UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON. U.S.A. Abstract: The uses of matrimony have always been standard practices for dynastic advancement through the ages. A perfect case study involves two important Italian families whose machinations had local implications and widespread international extensions. Their competitions are given particular point by the fact that one of the two families, the House of Savoy, was destined to become the dynasty around which the Modern State of Italy was created. This essay is, in part, a study in dynastic genealogies. But it is also a reminder of the wide impact of the crusading movements, beyond military operations and the creation of ephemeral Latin States in the Holy Land. Keywords: Matrimony, Crusading, Montferrat, Savoy, Levant. CRUZADA Y MATRIMONIO EN LAS POLÍTICAS DINÁSTICAS DE MONTFERRATO Y SABOYA Resumen: Los usos del matrimonio siempre han sido las prácticas estándar de ascenso dinástico a través de los tiempos. -

Johannes Vermeer's Mistress and Maid

Mahon et al. Herit Sci (2020) 8:30 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00375-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Johannes Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid: new discoveries cast light on changes to the composition and the discoloration of some paint passages Dorothy Mahon1, Silvia A. Centeno2* , Margaret Iacono3, Federico Carό2, Heike Stege4 and Andrea Obermeier4 Abstract Among the thirty-six paintings ascribed to the Dutch seventeenth century artist Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), Mistress and Maid, in The Frick Collection, stands out for the large-scale fgures set against a rather plain background depicting a barely discernible curtain. Although generally accepted as among the late works of the artist and dated to 1667–1668, for decades scholars have continued to puzzle over aspects of this portrayal. When the painting was cleaned and restored in 1952, attempts to understand the seeming lack of fnish and simplifed composition were hampered by the limited technical means available at that time. In 1968, Hermann Kühn included Mistress and Maid in his groundbreaking technical investigation ‘A Study of the Pigments and the Grounds Used by Jan Vermeer.’ In the present study, imaging by infrared refectography and macro-X-ray fuorescence (MA-XRF) revealed signifcant com- positional changes and drew focus to areas of suspected color change. Three of the samples taken by Hermann Kühn, and now in the archive of the Doerner Institut in Munich, were re-analyzed, along with a few paint samples taken from areas not examined in the 1968 study, using scanning electron microscopy–energy dispersive X-ray spectros- copy (SEM–EDS) and Raman spectroscopy. -

The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity

The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity By Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Dandelet, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Ignacio E. Navarrete Summer 2015 The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance, and Morisco Identity © 2015 by Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry All Rights Reserved The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity By Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California-Berkeley Thomas Dandelet, Chair Abstract In the Spanish city of Granada, beginning with its conquest by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, Christian aesthetics, briefly Gothic, and then classical were imposed on the landscape. There, the revival of classical Roman culture took place against the backdrop of Islamic civilization. The Renaissance was brought to the city by its conquerors along with Christianity and Castilian law. When Granada fell, many Muslim leaders fled to North Africa. Other elite families stayed, collaborated with the new rulers and began to promote this new classical culture. The Granada Venegas were one of the families that stayed, and participated in the Renaissance in Granada by sponsoring a group of writers and poets, and they served the crown in various military capacities. They were royal, having descended from a Sultan who had ruled Granada in 1431. Cidi Yahya Al Nayar, the heir to this family, converted to Christianity prior to the conquest. Thus he was one of the Morisco elites most respected by the conquerors. -

Bliography of Cyprus, 12°, Nicosia, 1886-89-94-190Κ0 and 1908, the Last Forming Part of "Excerpta," 4°, Cambridge, 1908

XAUDE DELAVAL COBHAM.] C6B (t I9ir>.) 4" - Η AN ATTEMPT AT A Κ Η BLIOGRAPHY OF CYPRUΘS Previously printed 1886 [152 titles]; 1889 [309]Ο; 1894 [497]; 1900 [728]; and 1908 [860 titles]Ι. Λ A NEW EDITIONΙ Β HRANGED ALPHABETICALLY WITΒH ADDITIONS. Η EDITED BY G. JEFFERYΚ , O.B.E.. F.S.A. ΙΑ PRICΡE 2s. 4kp. (2s. 6d.) Π Υ CYPRUS: Printed at the Government Printing Office, Nioosia. Κ 1 9 2 i). 'o be purchased at the Government Printing Office, Nicosia, Cyprus, from the Grown Agents for the Colonies, 4 Millbanh London, :^.W.l. Η Κ Η Θ ΙΟ Λ ΙΒ Β Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ t^S^s COLAUDE DELAY AL COBHAM.] (t 1915,) Η AN ATTEMPT AT A Κ Η BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CYPRUΘS Ο Previously printed 1886 [152 titles]; 1889 Ι[309]; 1894 [497]; 1900 [728]; and 1908 [860 titles]. Λ A NEW EDITIOΙNΒ Β ARRANGED ALPHABETICALL Y WITH ADDITIONS, Η Κ Α EDITED BY ΙG. JEFFERY, O.B.E., P.S.A. Ρ Π Υ CYPRUS : Printed at the Government Printing Office, Nicos r** i£P%fe\ Κ 7fi ' JON AlAtlA »JiAiOeHC.H i47t2 r <ZL^0 dC Η Κ Η Θ ΙΟ Λ ΙΒ Β Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ Η Κ Η Θ ΙΟ Λ DEDICATED TO HIS EXCELLENCY SIR EONALD STORESΒ, KT., C.M.G.^ O.B.E., Governor of Cyprus,Ι Β Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ Η Κ Η Θ ΙΟ Λ ΙΒ Β Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ PREFACE. -

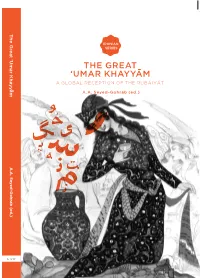

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Ungarn Jahrbuch

UNGARN–JAHRBUCH Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Hungarologie Herausgegeben von Zsolt K. Lengyel In Verbindung mit Gabriel Adriányi (Bonn), Joachim Bahlcke (Stuttgart) János Buza (Budapest), Holger Fischer (Hamburg) Lajos Gecsényi (Budapest), Horst Glassl (München) Ralf Thomas Göllner (Regensburg), Tuomo Lahdelma (Jyväskylä) István Monok (Budapest), Teréz Oborni (Budapest) Joachim von Puttkamer (Jena), Harald Roth (Potsdam) Hermann Scheuringer (Regensburg), Andrea Seidler (Wien) Gábor Ujváry (Budapest), András Vizkelety (Budapest) Band 33 Jahrgang 2016/2017 Verlag Friedrich Pustet Regensburg 2018 Ungarn–Jahrbuch. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Hungarologie Im Auftrag des Ungarischen Instituts München e. V. Redaktion: Zsolt K. Lengyel mit Florian Bucher, Krisztina Busa, Ralf Thomas Göllner Der Druck wurde vom Nationalen Kulturfonds (Nemzeti Kulturális Alap, Budapest) gefördert Redaktion: Ungarisches Institut der Universität Regensburg, Landshuter Straße 4, D-93047 Regensburg, Telefon: [0049] (0941) 943 5440, Telefax: [0049] (0941) 943 5441, [email protected], www.uni-regensburg.de/hungaricum-ungarisches-institut/ Beiträge: Publikationsangebote sind willkommen. Die Autorinnen und Autoren werden gebeten, ihre Texte elektronisch einzusenden. Die zur Veröffentlichung angenommenen Beiträge geben nicht unbedingt die Meinung der Herausgeber und Redaktion wieder. Für ihren Inhalt sind die jeweili gen Verfasser verantwortlich. Größere Kürzungen und Bearbei- tungen der Texte er folgen nach Absprache mit den Autorinnen und Autoren. Bibliografi sche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografi e; detaillierte bibliografi sche Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufb ar ISBN 978-3-7917-2811-7 Bestellung, Vertrieb und Abonnementverwaltung: Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Gutenbergstraße 8, 93051 Regensburg Tel. +49 (0) 941 92022-0, Fax +49 (0) 941 92022-330 [email protected] | www.verlag-pustet.de Preis des Einzelbandes: € (D) 44,– / € (A) 45,30 zzgl. -

Frankish-Venetian Cyprus: JSACE 3/16

97 Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering 2016/3/16 Frankish-Venetian Cyprus: JSACE 3/16 Effects of the Renaissance Frankish-Venetian Cyprus: Effects of the Renaissance on on the Ecclesiastical the Ecclesiastical Architecture of the Architecture of the Island Island Received 2016/09/22 Nasso Chrysochou Accepted after Assistant professor, Department of Architecture, Frederick University revision Demetriou Hamatsou 13, 1040 Nicosia 2016/10/24 Corresponding author: [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.sace.16.3.16278 The paper deals with the effects of the Renaissance on the Orthodox ecclesiastical architecture of the island. Even though the Latin monuments of the island have been thoroughly researched, there are only sporadic works that deal with the Orthodox ecclesiastical architecture of the period. The doctoral thesis of the author in waiting to be published is the only complete work on the subject. The methodology used, involved bibliographic research and to a large degree field research to establish the measurements of all the monuments. Cyprus during the late 15th to late 16th century was under Venetian rule but the government was more interested in establishing a defensive strategy against the threat of the Ottoman Empire rather than building the fine renaissance architecture that was realized in Italy. However, small morphological details and typologies managed to infiltrate the local architecture. This was done through the import of ideas and designs by Venetian architects and engineers who travelled around the colonies or through the use of easily transferable drawings and manuals of architects such as Serlio and Palladio. -

Social Structure and Civil War Mobilization in Montenegro

COUSINS IN ARMS: SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND CIVIL WAR MOBILIZATION IN MONTENEGRO By Vujo Ilić Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Supervisor: Erin Kristin Jenne Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2019 Abstract Many contemporary civil wars occur in segmentary societies, in which social structure rests on cohesive social groups. These wars tend to produce fast, extensive mobilizations of civilians, yet this reoccurring connection has mostly evaded a systematic analysis. This thesis explains why and how such social structure affects the dynamics of civil war mobilization. Unlike most existing civil war mobilization literature, the theory identifies both prewar and wartime factors, as well as both social groups and armed actors, as the determinants of mobilization. The theory proposes that civil war mobilization is determined primarily by the pre-war social structure and the wartime armed actors’ effects on social structure. The more pre-war social structure rests on cohesive social groups, the more it enables individuals to mobilize in insurgencies effectively. However, the pre-war structure is necessary but not a sufficient explanation for civil war mobilization. When a war starts, armed actors gain a crucial role. Mobilization dynamics during wartime depends on armed actors’ behavior, especially military and political decisions that affect social group cohesion. The horizontal ties of solidarity between group members enable fast and extensive collective action. However, if the armed actors disturb the vertical group status relations, this can change the extent and direction of civilian participation in the war.