Apriona Cinerea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insect Pest List by Host Tree and Reported Country

Insect pest list by host tree and reported country Scientific name Acalolepta cervina Hope, 1831 Teak canker grub|Eng Cerambycidae Coleoptera Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Tectona grandis Verbenaceae Teak-Jati Thailand Scientific name Amblypelta cocophaga Fruit spotting bug|eng Coconut Coreidae Hemiptera nutfall bug|Eng, Chinche del Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Agathis macrophylla Araucariaceae Kauri Solomon Islands Eucalyptus deglupta Myrtaceae Kamarere-Bagras Solomon Islands Scientific name Anoplophora glabripennis Motschulsky Asian longhorn beetle (ALB)|eng Cerambycidae Coleoptera Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Paraserianthes falcataria Leguminosae Sengon-Albizia-Falcata-Molucca albizia- China Moluccac sau-Jeungjing-Sengon-Batai-Mara- Falcata Populus spp. Salicaceae Poplar China Salix spp. Salicaceae Salix spp. China 05 November 2007 Page 1 of 35 Scientific name Aonidiella orientalis Newstead, Oriental scale|eng Diaspididae Homoptera 1894 Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Lovoa swynnertonii Meliaceae East African walnut Cameroon Azadirachta indica Meliaceae Melia indica-Neem Nigeria Scientific name Apethymus abdominalis Lepeletier, Tenthredinidae Hymenoptera 1823 Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Other Coniferous Other Coniferous Romania Scientific name Apriona germari Hope 1831 Long-horned beetle|eng Cerambycidae -

PRA on Apriona Species

EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE ET MEDITERRANEENNE POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES 16-22171 (13-18692) Only the yellow note is new compared to document 13-18692 Pest Risk Analysis for Apriona germari, A. japonica, A. cinerea Note: This PRA started 2011; as a result, three species of Apriona were added to the EPPO A1 List: Apriona germari, A. japonica and A. cinerea. However recent taxonomic changes have occurred with significant consequences on their geographical distributions. A. rugicollis is no longer considered as a synonym of A. germari but as a distinct species. A. japonica, which was previously considered to be a distinct species, has been synonymized with A. rugicollis. Finally, A. cinerea remains a separate species. Most of the interceptions reported in the EU as A. germari are in fact A. rugicollis. The outcomes of the PRA for these pests do not change. However A. germari has a more limited and a more tropical distribution than originally assessed, but it is considered that it could establish in Southern EPPO countries. The Panel on Phytosanitary Measures agreed with the addition of Apriona rugicollis to the A1 list. September 2013 EPPO 21 Boulevard Richard Lenoir 75011 Paris www.eppo.int [email protected] This risk assessment follows the EPPO Standard PM PM 5/3(5) Decision-support scheme for quarantine pests (available at http://archives.eppo.int/EPPOStandards/pra.htm) and uses the terminology defined in ISPM 5 Glossary of Phytosanitary Terms (available at https://www.ippc.int/index.php). This document was first elaborated by an Expert Working Group and then reviewed by the Panel on Phytosanitary Measures and if relevant other EPPO bodies. -

A Rectification in the Genus Apriona

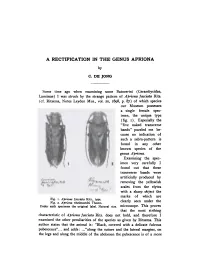

A RECTIFICATION IN THE GENUS APRIONA by C. DE JONG Some time ago when examining some Batocerini (Cerambycidae, Lamiinae) I was struck by the strange pattern of Apriona fasciata Rits. (cf. Ritsema, Notes Leyden Mus., vol. 20, 1898, p. 87) of which species our Museum possesses a single female spec• imen, the unique type (fig. 1). Especially the "five naked transverse bands" puzzled me be• cause no indication of such a zebra-pattern is found in any other known species of the genus Apriona. Examining the spec• imen very carefully I found out that these transverse bands were artificially produced by removing the yellowish scales from the elytra with a sharp object the marks of which are Fig. 1. Apriona fasciata Rits., type. clearly seen under the Fig. 2. Apriona rheimvardti Thorns. Under each specimen the original label. Natural size. microscope. This proves that the most striking characteristic of Apriona fasciata Rits. does not hold, and therefore I examined the other peculiarities of the species as given by Ritsema. This author states that the animal is: "Black, covered with a delicate fulvous pubescence"... and adds: ..."along the suture and the lateral margins, on the legs and along the middle of the abdomen the pubescence is of a more 268 DE JONG, A RECTIFICATION IN THE GENUS APRIONA greyish colour(I.e., p. 87). The blue-grey colour along the suture and the lateral margins is found in almost every species from the East Indies. The bluish-grey shade on the middle of the abdomen too is not a specific characteristic. -

Larval Peritrophic Matrix Yu-Bo Lin1,2†, Jing-Jing Rong1,2†, Xun-Fan Wei3, Zhuo-Xiao Sui3, Jinhua Xiao3 and Da-Wei Huang3*

Lin et al. Proteome Science (2021) 19:7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12953-021-00175-x RESEARCH Open Access Proteomics and ultrastructural analysis of Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larval peritrophic matrix Yu-Bo Lin1,2†, Jing-Jing Rong1,2†, Xun-Fan Wei3, Zhuo-Xiao Sui3, Jinhua Xiao3 and Da-Wei Huang3* Abstract Background: The black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) has significant economic potential. The larvae can be used in financially viable waste management systems, as they are voracious feeders able to efficiently convert low-quality waste into valuable biomass. However, most studies on H. illucens in recent decades have focused on optimizing their breeding and bioconversion conditions, while information on their biology is limited. Methods: About 200 fifth instar well-fed larvae were sacrificed in this work. The liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and scanning electron microscopy were employed in this study to perform a proteomic and ultrastructural analysis of the peritrophic matrix (PM) of H. illucens larvae. Results: A total of 565 proteins were identified in the PM samples of H. illucen, of which 177 proteins were predicted to contain signal peptides, bioinformatics analysis and manual curation determined 88 proteins may be associated with the PM, with functions in digestion, immunity, PM modulation, and others. The ultrastructure of the H. illucens larval PM observed by scanning electron microscopy shows a unique diamond-shaped chitin grid texture. Conclusions: It is the first and most comprehensive proteomics research about the PM of H. illucens larvae to date. All the proteins identified in this work has been discussed in details, except several unnamed or uncharacterized proteins, which should not be ignored and need further study. -

Parasitism and Suitability of Aprostocetus Brevipedicellus on Chinese Oak Silkworm, Antheraea Pernyi, a Dominant Factitious Host

insects Article Parasitism and Suitability of Aprostocetus brevipedicellus on Chinese Oak Silkworm, Antheraea pernyi, a Dominant Factitious Host Jing Wang 1, Yong-Ming Chen 1, Xiang-Bing Yang 2,* , Rui-E Lv 3, Nicolas Desneux 4 and Lian-Sheng Zang 1,5,* 1 Institute of Biological Control, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun 130118, China; [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (Y.-M.C.) 2 Subtropical Horticultural Research Station, United States Department of America, Agricultural Research Service, Miami, FL 33158, USA 3 Institute of Walnut, Longnan Economic Forest Research Institute, Wudu 746000, China; [email protected] 4 Institut Sophia Agrobiotech, Université Côte d’Azur, INRAE, CNRS, UMR ISA, 06000 Nice, France; [email protected] 5 Key Laboratory of Green Pesticide and Agricultural Bioengineering, Guizhou University, Guiyang 550025, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.-B.Y.); [email protected] (L.-S.Z.) Simple Summary: The egg parasitoid Aprostocetus brevipedicellus Yang and Cao (Eulophidae: Tetrastichi- nae) is one of the most promising biocontrol agents for forest pest control. Mass rearing of A. bre- vipedicellus is critical for large-scale field release programs, but the optimal rearing hosts are currently not documented. In this study, the parasitism of A. brevipedicellus and suitability of their offspring on Antheraea pernyi eggs with five different treatments were tested under laboratory conditions to determine Citation: Wang, J.; Chen, Y.-M.; Yang, the performance and suitability of A. brevipedicellus. Among the host egg treatments, A. brevipedicellus X.-B.; Lv, R.-E.; Desneux, N.; Zang, exhibited optimal parasitism on manually-extracted, unfertilized, and washed (MUW) eggs of A. -

The Major Arthropod Pests and Weeds of Agriculture in Southeast Asia

The Major Arthropod Pests and Weeds of Agriculture in Southeast Asia: Distribution, Importance and Origin D.F. Waterhouse (ACIAR Consultant in Plant Protection) ACIAR (Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research) Canberra AUSTRALIA The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has a special research competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR MO'lOGRAPH SERIES This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or deemed relevant to ACIAR's research objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on the Third World. © Australian Centre for 1I1lernational Agricultural Resl GPO Box 1571, Canberra, ACT, 2601 Waterhouse, D.F. 1993. The Major Arthropod Pests an Importance and Origin. Monograph No. 21, vi + 141pI- ISBN 1 86320077 0 Typeset by: Ms A. Ankers Publication Services Unit CSIRO Division of Entomology Canberra ACT Printed by Brown Prior Anderson, 5 Evans Street, Burwood, Victoria 3125 ii Contents Foreword v 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3 3. Contributors 5 4. Results 9 Tables 1. Major arthropod pests in Southeast Asia 10 2. The distribution and importance of major arthropod pests in Southeast Asia 27 3. The distribution and importance of the most important arthropod pests in Southeast Asia 40 4. Aggregated ratings for the most important arthropod pests 45 5. Origin of the arthropod pests scoring 5 + (or more) or, at least +++ in one country or ++ in two countries 49 6. -

Edible Insects

1.04cm spine for 208pg on 90g eco paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 171 FORESTRY 171 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 171 Edible insects Edible insects Future prospects for food and feed security Future prospects for food and feed security Edible insects have always been a part of human diets, but in some societies there remains a degree of disdain Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security and disgust for their consumption. Although the majority of consumed insects are gathered in forest habitats, mass-rearing systems are being developed in many countries. Insects offer a significant opportunity to merge traditional knowledge and modern science to improve human food security worldwide. This publication describes the contribution of insects to food security and examines future prospects for raising insects at a commercial scale to improve food and feed production, diversify diets, and support livelihoods in both developing and developed countries. It shows the many traditional and potential new uses of insects for direct human consumption and the opportunities for and constraints to farming them for food and feed. It examines the body of research on issues such as insect nutrition and food safety, the use of insects as animal feed, and the processing and preservation of insects and their products. It highlights the need to develop a regulatory framework to govern the use of insects for food security. And it presents case studies and examples from around the world. Edible insects are a promising alternative to the conventional production of meat, either for direct human consumption or for indirect use as feedstock. -

The Checklist of Longhorn Beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) from India

Zootaxa 4345 (1): 001–317 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4345.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1D070D1A-4F99-4EEF-BE30-7A88430F8AA7 ZOOTAXA 4345 The checklist of longhorn beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) from India B. KARIYANNA1,4, M. MOHAN2,5, RAJEEV GUPTA1 & FRANCESCO VITALI3 1Indira Gandhi Krishi Vishwavidyalaya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh-492012, India . E-mail: [email protected] 2ICAR-National Bureau of Agricultural Insect Resources, Bangalore, Karnataka-560024, India 3National Museum of Natural History of Luxembourg, Münster Rd. 24, L-2160 Luxembourg, Luxembourg 4Current address: University of Agriculture Science, Raichur, Karnataka-584101, India 5Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by Q. Wang: 22 Jun. 2017; published: 9 Nov. 2017 B. KARIYANNA, M. MOHAN, RAJEEV GUPTA & FRANCESCO VITALI The checklist of longhorn beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) from India (Zootaxa 4345) 317 pp.; 30 cm. 9 Nov. 2017 ISBN 978-1-77670-258-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77670-259-6 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2017 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2017 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. -

Longhorn Beetles (Cerambycidae: Coleoptera) of Himachal Pradesh 405 ISSN 0375-1511

MITRA et al. : Longhorn beetles (Cerambycidae: Coleoptera) of Himachal Pradesh 405 ISSN 0375-1511 Rec. zool. Surv. India : 115(Part-4) : 405-409, 2015 LONGHORN BEETLES (CERAMBYCIDAE: COLEOPTERA) OF HIMACHAL PRADESH BULGANIN MITRA#, AMITAVA MAJUMDER, UDIPTA CHAKRABORTI, PRIYANKA DAS AND KAUSHIK MALLICK* Zoological Survey of India, Prani Vigyan Bhavan, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053, West Bengal, India. * Post Graduate Department of Zoology, Asutosh College, Kolkata – 700026 #Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION complete bibliography on the works of cerambycid The taxonomic study of the family beetles of this Himalayan state in India. cerambycidae is very poor in Himachal Pradesh. Subfamily LAMIINAE Contributions of Breuning (1937, 1958, 1965), Tribe ANCYLONOTINI Lacordaire, 1869 Beeson and Bhatia (1939), Basak and Biswas 1. Palimnodes ducalis (Bates, 1884) (1993), Mukhopadhyay (2011), Saha et al. (2013) 1884. Apalimna ducalis Bates, The Journal of the Linnean were enriched the cerambycid fauna of this state. Society of London. Zoology, 18: 242. Type Locality: Later, few publications were made on other North India, Type Repository: Muséum National aspects than taxonomy of cerambycidae by Uniyal d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris. and Mathur (1998), Singh, and Verma (1998), 2006. Parapalimna ducalis; Weigel, Biodiversität und Naturausstattung im Himalaya, II. V: 503. Bhargava and Uniyal (2011). Therefore, an attempt Material examined: 1 ex, Kulu, Himachal has been taken to prepare a consolidated taxonomic Pradesh, -

Coleoptera: Cerambycidae

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2017; 5(5): 1450-1455 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Important longhorn beetles (Coleoptera: JEZS 2017; 5(5): 1450-1455 © 2017 JEZS Cerambycidae) of horticulture crops Received: 07-07-2017 Accepted: 08-08-2017 Kariyanna B, Mohan M, Utpal Das, Ravi Biradar and Anusha Hugar A Kariyanna B University of Agriculture Science, Raichur, Karnataka, Abstract India The longhorn beetles are distributed globally from sea level to mountain sites as high as 4,200 m altitude wherever their host floras are available. All the members of the family Cerambycidae are either Mohan M phytophagous or xylophagous. Many species are important pests of forests, plantations, fruit and street ICAR-National Bureau of trees. Usually, the adults are known to girdle twigs or branches to feed on foliage or blossoms. The Agricultural Insect Resources, longhorn beetles inflict damage to plants by feeding internally the heart wood or sapwood and sometimes Bangalore, Karnataka, India acting as root borers or gall formers. In recent times extensive cultivation of crop combined with greenhouse effect causes many longhorn beetles to become serious pests in horticulture ecosystem. Utpal Das Mainly the plantations and fruit crops are threatened by longhorn beetle which results in reduced vigour University of Agriculture Science, Raichur, Karnataka, and complete death of plants. India Keywords: Longhorn beetles, Horticulture crops, Serious Pest, Damage Ravi Biradar University of Agriculture Introduction Science, Raichur, Karnataka, Of the estimated 1.088 million animal species (excluding synonyms and infra-species) India described worldwide, insects represent 0.795 million (73%) of the species, and beetles account for about 0.236 million (30%) [1]. -

Some New Cerambycidae

SOME NEW CERAMBYCIDAE by C. DE JONG TWO NEW SPECIES OF THE GENUS APRIONA CHEVR. (CERAMBYCIDAE, LAMIINAE, BATOCERINI) Apriona hageni nov. spec. c$ (fig. i). Length 32 mm, breadth at the shoulders 9.2 mm, length of the antennae 56 mm. Locality: Sumatra (Tandjong Morawa, Serdang, N. E. Sumatra, Dr. B. Hagen). Holotype. Closely related to Apriona cylindrica Thorns., more slender. Thorax less compressed, anterior transverse furrow less distinct and curved. Elytra almost parallel, with light sepia-brown pubescence and ornated with many milky white spots, which are irregularly spread over the surface. Shoul• ders not armed with a tooth. Basal quarter of the elytra with black, shining granules, which diminish from the shoul• der towards the suture, where they are nearly absent. Apex truncate. Sutural angle with a thorn. Scutellum posteriorly pig. 1. Apriona hageni nov. spec, truncate with rounded angles. Type tf. Natural size Antennae dark brown with greyish pubescence. Legs dark brown with yellowish grey pubescence. Ventral surface yellowish grey like the legs. On both sides runs a white line from the side of the prothorax to the end of the abdomen. Apriona neglectissima nov. spec. cf. Length 30 mm, breadth at the shoulders 10.2 mm, length of the antennae 32.5 mm. 76 C. DE JONG Locality: Borneo (Sambas, Bosscha, ex. coll. Veth). Holotype. Closely related to Apriona swainsoni Hope, which was described from Assam and Tonkin. In the colour of the elytra it bears resemblance to Apriona neglecta Rits., under which name I found it in the collection of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie at Leiden, but the ventral surface shows a number of bright spots (indicated with //////// in fig. -

Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and Phylogenetic Relationships Within Cerambycidae

The complete mitochondrial genomes of five longicorn beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and phylogenetic relationships within Cerambycidae Jun Wang1, Xin-Yi Dai1, Xiao-Dong Xu1, Zi-Yi Zhang1, Dan-Na Yu1,2, Kenneth B. Storey3 and Jia-Yong Zhang1,2 1 College of Chemistry and Life Science, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China 2 Key lab of wildlife biotechnology, Conservation and Utilization of Zhejiang Province, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China 3 Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada ABSTRACT Cerambycidae is one of the most diversified groups within Coleoptera and includes nearly 35,000 known species. The relationships at the subfamily level within Cer- ambycidae have not been convincingly demonstrated and the gene rearrangement of mitochondrial genomes in Cerambycidae remains unclear due to the low numbers of se- quenced mitogenomes. In the present study, we determined five complete mitogenomes of Cerambycidae and investigated the phylogenetic relationship among the subfamilies of Cerambycidae based on mitogenomes. The mitogenomic arrangement of all five species was identical to the ancestral Cerambycidae type without gene rearrangement. Remarkably, however, two large intergenic spacers were detected in the mitogenome of Pterolophia sp. ZJY-2019. The origins of these intergenic spacers could be explained by the slipped-strand mispairing and duplication/random loss models. A conserved motif was found between trnS2 and nad1 gene, which was proposed to be a binding site of a transcription termination peptide. Also, tandem repeat units were identified in the A C T-rich region of all five mitogenomes. The monophyly of Lamiinae and Prioninae was Submitted 14 May 2019 strongly supported by both MrBayes and RAxML analyses based on nucleotide datasets, Accepted 6 August 2019 whereas the Cerambycinae and Lepturinae were recovered as non-monophyletic.