Coercion As a Political Tool in Queer Manga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

READING FOOD in BOYS LOVE MANGA a Gastronomic Study of Food and Male Homosexuality in the Manga Work of Yoshinaga Fumi

READING FOOD IN BOYS LOVE MANGA A Gastronomic Study of Food and Male Homosexuality in the Manga Work of Yoshinaga Fumi Xuan Bach Tran A dissertation submitted to AUT University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Gastronomy 2018 School of Hospitality and Tourism Primary Supervisor: Hamish Bremner Secondary Supervisor: Andrew Douglas TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................. iii ATTESTATION OF AUTHORSHIP ................................................................. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. v ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1 I. Why Reading Food in Boys Love Manga? ............................................. 1 II. Food, Gender, Manga and Lives of The Ordinary................................... 3 III. Yoshinaga Fumi’s manga work as texts ................................................. 4 IV. Research Question ................................................................................. 5 V. Chapters Outlines................................................................................... 5 VI. A Note on Japanese Names, Terminology, and the Manga Way ............. 6 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................... -

Cobra the Animation Review

Cobra the animation review [Review] Cobra: The Animation. by Gerald Rathkolb October 12, SHARE. Sometimes, it's refreshing to find something that has little concern with following. May 27, Title: Cobra the Animation Genre: Action/Adventure Company: Magic Bus Format: 12 episodes Dates: 2 Jan to 27 Mar Synopsis: Cobra. Space Adventure Cobra is a hangover from the 80's. it isn't reproduced in this review simply because the number of zeros would look silly. Get ready to blast off, rip-off, and face-off as the action explodes in COBRA THE ANIMATION! The Review: Audio: The audio presentation for. Cobra The Animation – Blu-ray Review. written by Alex Harrison December 5, Sometimes you get a show that is fun and captures people's imagination. visits a Virtual Reality parlor to live out his vague male fantasies, but the experience instead revives memories of being the great space rogue Cobra, scourge of. Here's a quick review. I think that my biggest issue with Cobra is that I unfortunately happened to watch one of the worst Cobra episodes as my. A good reviewer friend of mine, Andrew Shelton at the Anime Meta-Review, has a It's a rating I wish I had when it came to shows like Space Adventure Cobra. Cobra Anime Anthology ?list=PLyldWtGPdps0xDpxmZ95AMcS4wzST1qkq. Not quite a full review, just a quick look at the new Space Adventure Cobra tv series (aka Cobra: the Animation. This isn't always the case though. Sometimes you wonder this same thing about series that are actually good, such as Cobra the Animation. -

Radicalizing Romance: Subculture, Sex, and Media at the Margins

RADICALIZING ROMANCE: SUBCULTURE, SEX, AND MEDIA AT THE MARGINS By ANDREA WOOD A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Andrea Wood 2 To my father—Paul Wood—for teaching me the value of independent thought, providing me with opportunities to see the world, and always encouraging me to pursue my dreams 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Kim Emery, my dissertation supervisor, for her constant encouragement, constructive criticism, and availability throughout all stages of researching and writing this project. In addition, many thanks go to Kenneth Kidd and Trysh Travis for their willingness to ask me challenging questions about my work that helped me better conceptualize my purpose and aims. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family who provided me with emotional and financial support at difficult stages in this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................7 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................11 -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

The Journal of a London Playgoer from 1851 to 1866

BOOKS AND PAPERS HENRY MORLEY 1851 1866 II THE JOURNAL LONDON PLAYGOER FROM 1851 TO 1866 HENRY MORLEY, LL.D, EMERITUS PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE IN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE. LONDON LONDON GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, LIMITED BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL GLASGOW, MANCHESTER, AND NEW. .YORK < ' ' PN PROLOGUE. THE writer who first taught Englishmen to look for prin- ciples worth study in the common use of speech, expecting censure for choice of a topic without dignity, excused him- self with this tale out of Aristotle. When Heraclitus lived, a famous Greek, there were some persons, led by curiosity to see him, who found him warming himself in his kitchen, and paused at the threshold because of the meanness of the " place. But the philosopher said lo them, Enter boldly, " for here too there are Gods". The Gods" in the play- house are, indeed, those who receive outside its walls least honour among men, and they have a present right to be its Gods, I fear, not only because they are throned aloft, but also because theirs is the mind that regulates the action of the mimic world below. They rule, and why ? Is not the educated man himself to blame when he turns with a shrug from the too often humiliating list of an evening's perform- ances at all the theatres, to say lightly that the stage is ruined, and thereupon make merit of withdrawing all atten- tion from the players ? The better the stage the better the town. If the stage were what it ought to be, and what good it actors heartily desire to make it, would teach the public to appreciate what is most worthy also in the sister arts, while its own influence would be very strong for good. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

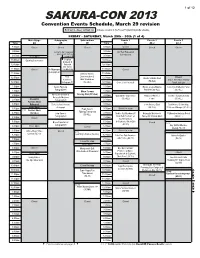

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

The Function of Manga to Shape and Reflect Japanese Identity

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: From Samurai to Manga: The Function of Manga to Shape and Reflect Japanese Identity Author(s): Maria Rankin-Brown and Morris Brown, Jr. Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XVI (2012), pp. 75 - 92 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xvi-2012/rankin-brown-manga- research.pdf ______________________________________________________________ FROM SAMURAI TO MANGA: THE FUNCTION OF MANGA TO SHAPE AND REFLECT JAPANESE IDENTITY Maria Rankin-Brown Pacific Union College Morris Brown, Jr. California State University, Chico Literature has various functions: to instruct, to entertain, to subvert, to inspire, to express creativity, to find commonality, to heal, to isolate, to exclude, and even to reflect and shape identity. The genre of manga – Japanese comics – has served many of these functions in Japanese society. Moreover, “Manga also depicts other social phenomena, such as social order and hierarchy, sexism, racism, ageism, classism, and so on.”1 Anyone familiar with Bleach, Dragonball Z, Inuyasha, Full Metal Alchemist, Pokémon, or Sailor Moon, can attest to manga’s worldwide appeal and its ability to reflect societal values. The $4.2 billion manga industry, which comprises nearly one quarter of Japan’s printed material, cannot be ignored.2 While comics in the West have been regarded, for many years, as light-hearted entertainment (Archie comics), or for political commentary (the Doonesbury series) the manga industry in Japan grew to encompass genres beyond what the West offers. These include: action, adventure, comedy, crime, detective, fantasy, harem, historical, horror, magic, martial arts, medical, mystery, occult, pachinko (gambling), romance, science fiction, supernatural, and suspense series, reaching a wider audience than that of Western comics. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

(Unabridged) K

Audiobook 12 Before 13 Greenwald, Lisa Audiobook 13 and Counting Greenwald, Lisa Audiobook A Nancy Drew Christmas (unabridged) Keene, Carolyn Audiobook A Virgin River Christmas:(unabridged) Carr, Robyn Audiobook Abby in Oz Mlynowski, Sarah Audiobook Admission Buxbaum, Julie Audiobook Adventures of Captain Underpants Pilkey, Dav Audiobook All That Glitters Steel, Danielle Audiobook All Your Twisted Secrets Urban, Diana Audiobook Allies Gratz, Alan ; Cline, Jamie McGee, Katharine ; Pressley, Audiobook American Royals Brittany Audiobook Archenemies Meyer, Marissa Audiobook Artemis Fowl Colfer, Eoin Tyson, Neil deGrasse ; Mone, Audiobook Astrophysics for Young People in a Hurry Gregory Audiobook Aurora Rising Kaufman, Amie ; Kristoff, Jay Audiobook Awakening Roberts, Nora Audiobook Awesome Dog 5000 Dean, Justin Audiobook Bad Seed John, Jory Audiobook Bait and Witch(unabridged) Sanders, Angela M. Audiobook Batman Lu, Marie Audiobook Best Babysitters Ever Cala, Caroline Audiobook Best of Me Sedaris, David DiCamillo, Kate ; Marie, Audiobook Beverly, Right Here Jorjeana Audiobook Big Nate Flips Out Peirce, Lincoln Audiobook Big Nate Goes for Broke Peirce, Lincoln Audiobook Big Nate in the Zone Peirce, Lincoln Mlynowski, Sarah ; Myracle, Audiobook Big Shrink Lauren ; Jenkins, Emily Audiobook Black Panther Smith, Ronald L. Audiobook Blood in the Dust Johnstone, William W. Mass, Wendy ; Stead, Audiobook Bob Rebecca Audiobook Book With No Pictures Novak, B. J. Audiobook Boxcar Children Warner, Gertrude Chandler Audiobook Brightest Night Sutherland, -

History 146C: a History of Manga Fall 2019; Monday and Wednesday 12:00-1:15; Brighton Hall 214

History 146C: A History of Manga Fall 2019; Monday and Wednesday 12:00-1:15; Brighton Hall 214 Insufficient Direction, by Moyoco Anno This syllabus is subject to change at any time. Changes will be clearly explained in class, but it is the student’s responsibility to stay abreast of the changes. General Information Prof. Jeffrey Dym http://www.csus.edu/faculty/d/dym/ Office: Tahoe 3088 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays 1:30-3:00, Tuesdays & Thursdays 10:30-11:30, and by appointment Catalog Description HIST 146C: A survey of the history of manga (Japanese graphic novels) that will trace the historical antecedents of manga from ancient Japan to today. The course will focus on major artists, genres, and works of manga produced in Japan and translated into English. 3 units. GE Area: C-2 1 Course Description Manga is one of the most important art forms to emerge from Japan. Its importance as a medium of visual culture and storytelling cannot be denied. The aim of this course is to introduce students and to expose students to as much of the history and breadth of manga as possible. The breadth and scope of manga is limitless, as every imaginable genre exists. With over 10,000 manga being published every year (roughly one third of all published material in Japan), there is no way that one course can cover the complete history of manga, but we will cover as much as possible. We will read a number of manga together as a class and discuss them.