The Journal of a London Playgoer from 1851 to 1866

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections and Reflections, a Professional Autobiography

... • . .... (fcl fa Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the estate of MARION WALKER RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS. RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS OF J. E. PLANCHE, (somerset herald). ^ |]rofcssiona( gaifobbcjrapbtr. " I ran it through, even from my boyish days, To the very moment that he bade me tell it." Othello, Act i., Scene 3. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 18, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND. 1872. ..4^ rights reserved. LONDON BRADBURV, EVANS, AND CO., PRINTERS, WHITBFRIAR,-!. ——— CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. VAGK Another Mission to Paris—Production of " Le Domino Noir"— Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gore—Dinner at Lord Lyndhurst's Mons. Allou, Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of France—The Duke D'Istrie and his Collection of Armour Her Majesty's Coronation—" Royal Records "—Extension of Licence to the Olympic and Adelphi Theatres—" The Drama's Levee"—Trip to Calais with Madame Yestris and Charles Mathews previous to their departure for America—Visit to Tournehem—Sketching Excursion with Charles Mathews Marriage of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews—They sail for New York—The Olympic Theatre opened under my Direc- tion—Farren and Mrs. Nisbett engaged—Unexpected return of Mr. and Mrs. Mathews—Re-appearance of the latter in " Blue Beard "— " Faint Heart never won Fair Lady "—"The Garrick Fever"—Charles Mathews takes Covent Garden Theatre CHAPTER II. Death of Haynes Bayly—Benefit at Drury Lane for his Widow and Family—Letters respecting it from Theodore Hook and Mrs. Charles Gore—Fortunate Results of the Benefit—Tho Honourable Edmund Byng—Annual Dinner established by him in aid of Thomas Dibdin—Mr. -

A Moor Propre: Charles Albert Fechter's Othello

A MOOR PROPRE: CHARLES ALBERT FECHTER'S OTHELLO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Scott Phillips, B.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University •· 1992 Thesis Committee: Approved by Alan Woods Joy Reilly Adviser Department of Theatre swift, light-footed, and strange, with his own dark face in a rage,/ Scorning the time-honoured rules Of the actor's conventional schools,/ Tenderly, thoughtfully, earnestly, FECHTER comes on to the stage. (From "The Three Othellos," Fun 9 Nov. 1861: 76.} Copyright by Matthew Scott Phillips ©1992 J • To My Wife Margaret Freehling Phillips ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express heartfelt appreciation to the members of my thesis committee: to my adviser, Dr. Alan Woods, whose guidance and insight made possible the completion of this thesis, and Dr. Joy Reilly, for whose unflagging encouragement I will be eternally grateful. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable services of the British Library, the Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Theatre Research Institute and its curator, Nena Couch. The support and encouragement given me by my family has been outstanding. I thank my father for raising my spirits when I needed it and my mother, whose selflessness has made the fulfillment of so many of my goals possible, for putting up with me. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Maggie, for her courage, sacrifice and unwavering faith in me. Without her I would not have come this far, and without her I could go no further. -

Irish Playwrights and the Dunedin Stage in 1862: Theatre Patrons Performing Civility

Irish Playwrights and the Dunedin Stage in 1862: Theatre Patrons Performing Civility PETER KUCH Irish Plays on the Dunedin Stage in 1862 A first-rate actor of Irish characters is indispensible on a London Stage. Cumberland’s British Theatre, 1828. Between 1862 and 1869 there were some 300 performances of Irish plays in Dunedin‘s theatres. Kuch, Irish Society for Theatre Research, 2010. A mere 14 years after it was founded by Presbyterians as a distinctly Scottish city that was ―in the world but not of the world,‖ Dunedin possessed two splendid theatres that during their first decade of operation staged some 300 performances of Irish plays and plays by Irish playwrights. How did this happen? Why Irish plays? Why Irish playwrights? And why were two theatres, with capacities of 1500 and 1330 persons, opened in Dunedin a year before Otago Boys High School was founded, five years before the foundations of First Church were laid, and seven years before the Provincial Council turned its attentions to establishing a University?1 Initially, it was the theatres that were a source of civic pride. According to an 1862 issue of the Otago Witness, Dunedin possessed ―two of the handsomest theatres in the Australian colonies.‖ 2 While there are doubtless many explanations for this rush to build theatres, the short answer is that the city was overtaken by the very world it had sought to isolate itself from. But this is an answer that invites explanation. First, it has to do with what was on offer on stage. It has been well established by theatre historians that Irish playwrights (particularly Dion Boucicault) and Irish plays (particularly comedy and melodrama) dominated the nineteenth-century stage—whether in Dublin or London or New York.3 It is also well known that, by the time the Theatre Royal and The Princess Theatre were opened in Dunedin, the ―legitimate drama‖4 had become widely if not firmly established as the secular vehicle for social and cultural improvement. -

[, F/ V C Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET

WOMEN IN AMERICAN THEATRE, 1850-1870: A STUDY IN PROFESSIONAL EQUITY by Edna Hammer Cooley I i i Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in parti.al fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ /, ,, ·' I . 1986 I/ '/ ' ·, Cop~ I , JI ,)() I co uI (~; 1 ,[, f/ v c Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850-1870: A Study in Professional Equity Name of Candidate: Edna Hammer Cooley Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation and Approved: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor Dept. of Communication Arts & Theatre Date Approved: .;;Jo .i? p ,vt_,,/ /9Y ,6 u ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850- 1870~ A Study_ in Professional Equi!:Y Edna Hammer Cooley, Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor of Communication Arts and Theatre Department of Communication Arts and Theatre This study supports the contention that women in the American theatre from 1850 to 1870 experienced a unique degree of professional equity with men in the atre. The time-frame has been selected for two reasons: (1) actresses active after 1870 have been the subject of several dissertations and scholarly studies, while relatively little research has been completed on women active on the American stage prior to 1870, and (2) prior to 1850 there was limited theatre activity in this country and very few professional actresses. A general description of mid-nineteenth-century theatre and its social context is provided, including a summary of major developments in theatre in New York and other cities from 1850 to 1870, discussions of the star system, the combination company, and the mid-century audience. -

Reminiscences of J. L. Toole

PRE FA C E. W H AT a different thing talking is compared with writing ! I am on tour when I jot down th is fl h profound re ection . My dear friend J osep Hatton has been on my track since we parted in town , a month or two ago , with this one message , by post and telegram— “ You ought to write the ! ” Preface , every word of it As it is my own I I Preface of course ought , and of course have done so . But wh ile the writing of it has been a labour of love , it has bothered me a good deal u more than a labour of love is s pposed to do . Many times I have adm ired the skill with which my collaborator has written , i n these pages , stories which seemed to me to require , for a complete n narratio , the point one puts i nto an anecdote I when acting it . am occasionally called upon to I make a speech i n public . Well , get along now and then pretty well , thanks to the inspiration that seems to come to me f rom the friendly sym pathy of my aud ience but there is no inspiration P REFACE . in a blank sheet of paper , and there is no applause in pen s and ink . When one makes a speech one seeks kindly faces around one , and it is wonderful what assistance there is in a little applause . You take up the report of a speech in a newspaper ; “ i s you see that it peppered with Laughter , ” s Applause , Loud cheer , and so on that sets you reading it , and carries you on to the end . -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

(Unabridged) K

Audiobook 12 Before 13 Greenwald, Lisa Audiobook 13 and Counting Greenwald, Lisa Audiobook A Nancy Drew Christmas (unabridged) Keene, Carolyn Audiobook A Virgin River Christmas:(unabridged) Carr, Robyn Audiobook Abby in Oz Mlynowski, Sarah Audiobook Admission Buxbaum, Julie Audiobook Adventures of Captain Underpants Pilkey, Dav Audiobook All That Glitters Steel, Danielle Audiobook All Your Twisted Secrets Urban, Diana Audiobook Allies Gratz, Alan ; Cline, Jamie McGee, Katharine ; Pressley, Audiobook American Royals Brittany Audiobook Archenemies Meyer, Marissa Audiobook Artemis Fowl Colfer, Eoin Tyson, Neil deGrasse ; Mone, Audiobook Astrophysics for Young People in a Hurry Gregory Audiobook Aurora Rising Kaufman, Amie ; Kristoff, Jay Audiobook Awakening Roberts, Nora Audiobook Awesome Dog 5000 Dean, Justin Audiobook Bad Seed John, Jory Audiobook Bait and Witch(unabridged) Sanders, Angela M. Audiobook Batman Lu, Marie Audiobook Best Babysitters Ever Cala, Caroline Audiobook Best of Me Sedaris, David DiCamillo, Kate ; Marie, Audiobook Beverly, Right Here Jorjeana Audiobook Big Nate Flips Out Peirce, Lincoln Audiobook Big Nate Goes for Broke Peirce, Lincoln Audiobook Big Nate in the Zone Peirce, Lincoln Mlynowski, Sarah ; Myracle, Audiobook Big Shrink Lauren ; Jenkins, Emily Audiobook Black Panther Smith, Ronald L. Audiobook Blood in the Dust Johnstone, William W. Mass, Wendy ; Stead, Audiobook Bob Rebecca Audiobook Book With No Pictures Novak, B. J. Audiobook Boxcar Children Warner, Gertrude Chandler Audiobook Brightest Night Sutherland, -

Some Experiences of a Barrister's Life

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I " • GIFT OF John Garber Palacbe Helen Palacbe Lansdale from the estate of the late judge John Garber Slips for Librarians to paste on Catalogue Cards. N. B.— Take out carefully, leaving about quarter of an inch at the back. To do otherwise would, in some cases, release other leaves. BALLANTINE, WILLIAM. SOME EXPERI ENCES OF A BARRISTER'S LIFE. By Mr. SERJEANT BALLANTINE. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1882. i2mo, pp. xxiv., 527. SOME EXPERIENCES OF A BARRIS TER'S LIFE. By Mr. SERJEANT BALLANTINE. New York : Henry Holt & Co., 1882. izrno, pp. xxiv., 527. BIOGRAPHY. SOME EXPERIENCES OF A BAR RISTER'S LIFE. By MR. SERJEANT BALLANTINE. New York : Henry Holt & Co., 1882. 12100, pp. xxiv., 527. MEMOIRS. SOME EXPERIENCES OF A BARRIS TER'S LIFE. By MR. SERJEANT BALLANTINE. New York : Henry Holt & Co., 1882. i2mo, pp. xxiv., 527. SOME EXPERIENCES OP A BARRISTER'S LIFE MR SERJEANT BALLANTINE NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1882 PREFATORY NOTE. T HAVE felt at a loss to know in what manner I ought to introduce the following pages to the reader, and should have been inclined to launch them without a word of preface, but that it might be thought that I formed an exaggerated estimate of their intrinsic worth, which certainly is not the case. What I have striven to do, and trust I have suc ceeded in doing, has been to adhere strictly to facts in the incidents related ; and the conclusions ex pressed are the honest results of such experience as a long professional life, not unmixed with other asso ciations, has enabled me to form. -

A Study of the Management of Charles Kean at The

A STUDY OF THE MANAGEMENT OF CHARLES KEAN AT THE PRINCESS’S THEATRE; l850-l859 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By BUDGE THRELKELD, B. A., M. A. **** The Ohio State University 1955 Approved by Adviser Department of Speech PREFACE When a person approaches a subject with the idea in mind of using that subject for the purpose of a detailed study, he does so with certain provisions. In this instance I was anxious to do a dissertation which would require an extended use of The Ohio State University Theatre Collec tion and which would enable me, at the same time, to do original research. The recent collection, on microfilm, of prompt books of theatrical productions during the nineteenth century provided an opportunity to explore that area in search of a suitable problem. The. possibility of doing research on the management of Charles Kean at the Royal Princesses Theatre was enhanced when tentative probings revealed that the importance of Kean*s management was recog nized by every authority in the field. However, specific and detailed information about the Princesses Theatre and its management was meagre indeed. Further examination of some of the prompt books prepared by Kean for his outstand ing productions at the Princesses convinced me that evidence was available here that would establish Kean as a director in the modern sense of the word. This was an interesting revelation because the principle of the directorial approach to play production is generally accepted to date from the advent of the famous Saxe-Meiningen company. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 NEGOTIATION AND LEGITIMATION: THE BRITISH PERIODICAL PRESS AND THE STAGE 1832-1892 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Scott Phillips, M.A. -

Cross-Dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media Sheena Marie Woods University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 The aF scination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media Sheena Marie Woods University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Japanese Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Theatre History Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Woods, Sheena Marie, "The asF cination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1273. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 44 The Fascination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies By Sheena Woods University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in International Relations, 2012 University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Asian Studies, 2012 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _______________________ Dr. Elizabeth Markham Thesis Director ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Tatsuya Fukushima Dr. Rembrandt Wolpert Committee Member Committee Member 4 4 Abstract The performativity of gender through cross-dressing has been a staple in Japanese media throughout the centuries. This thesis engages with the pervasiveness of cross-dressing in popular Japanese media, from the modern shōjo gender-bender genre of manga and anime to the traditional Japanese theatre. -

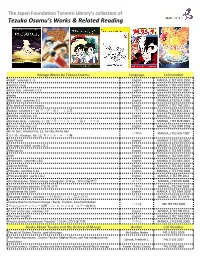

Tezuka Osamu Booklist

The Japan Foundation Toronto Library’s collection of Tezuka Osamu’s Works & Related Reading Manga Works by Tezuka Osamu Language Call number Adolf : volumes 1 - 5 English MANGA_E TEZ ADO 1995 Apollo's song English MANGA_E TEZ APO 2007 Astro boy : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ AST 2002 Ayako English MANGA_E TEZ AYA 2010 Black Jack : volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ BLA 2008 The book of human insects English MANGA_E TEZ THE 2011 Budda : volumes 1~14 ブッダ:第1-14巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUD 2011 Buddha : volumes 1-8 English MANGA_E TEZ BUD 2003 Burakku Jakku : volumes 1~22 ブラックジャック:第1-22巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUR 2004 Dororo : Volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ DOR 2008 Hi no tori : Hinotori No. 12, Girisha, Roma hen 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ HIN 1987 火の鳥 : Hinotori. No. 12, ギリシャ・ローマ編 Lost World English MANGA_E TEZ LOS 2003 Message to Adolf : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ MES 2012 Metropolis English MANGA_E TEZ MET 2003 MW English MANGA_E TEZ MW 2007 Nextworld : volumes 1 &2 English MANGA_E TEZ NEX 2003 Ode to Kirihito English MANGA_E TEZ ODE 2006 Phoenix : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ PHO 2003 Princess knight : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ PRI 2011 Shintakarajima : boken manga monogatari 新寳島 : 冒険漫画物語 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Shintakarajima tokuhon 新寶島 読本 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Swallowing the Earth English MANGA_E TEZ SWA 2009 Tetsuwan Atomu : volumes 1~17 鉄腕アトム:第 1-17 巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ TET 1979 Tezuka Osamu no Dizuni manga : Banbi, Pinokio : kara fukkokuban 日本語 REF TEZ TEZ 2005 手塚治虫のディズニー漫画 : バンビ, ピノキオ : カラー復刻版 Triton of the sea : volumes 1-2 English MANGA_E TEZ TRI 2013 The Twin Knights English MANGA_E TEZ TWI 2013 Tezuka Osamu kessakusen "kazoku"手塚治虫傑作選 家族 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ KAZ 2008 Books About Tezuka and the History of Manga Author Call Number The art of Osamu Tezuka : god of manga McCarthy, Helen 741.5 M32 2009 The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga/anime Schodt, Frederik L.