[, F/ V C Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections and Reflections, a Professional Autobiography

... • . .... (fcl fa Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the estate of MARION WALKER RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS. RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS OF J. E. PLANCHE, (somerset herald). ^ |]rofcssiona( gaifobbcjrapbtr. " I ran it through, even from my boyish days, To the very moment that he bade me tell it." Othello, Act i., Scene 3. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 18, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND. 1872. ..4^ rights reserved. LONDON BRADBURV, EVANS, AND CO., PRINTERS, WHITBFRIAR,-!. ——— CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. VAGK Another Mission to Paris—Production of " Le Domino Noir"— Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gore—Dinner at Lord Lyndhurst's Mons. Allou, Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of France—The Duke D'Istrie and his Collection of Armour Her Majesty's Coronation—" Royal Records "—Extension of Licence to the Olympic and Adelphi Theatres—" The Drama's Levee"—Trip to Calais with Madame Yestris and Charles Mathews previous to their departure for America—Visit to Tournehem—Sketching Excursion with Charles Mathews Marriage of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews—They sail for New York—The Olympic Theatre opened under my Direc- tion—Farren and Mrs. Nisbett engaged—Unexpected return of Mr. and Mrs. Mathews—Re-appearance of the latter in " Blue Beard "— " Faint Heart never won Fair Lady "—"The Garrick Fever"—Charles Mathews takes Covent Garden Theatre CHAPTER II. Death of Haynes Bayly—Benefit at Drury Lane for his Widow and Family—Letters respecting it from Theodore Hook and Mrs. Charles Gore—Fortunate Results of the Benefit—Tho Honourable Edmund Byng—Annual Dinner established by him in aid of Thomas Dibdin—Mr. -

Hull Fa1nilies United States

Hull Fa1nilies • lll The United States By REV. WILLIAM E. HULL Copyright 1964 by WILLIAM E. HULL Printed by WOODBURN PRINTING CO - INC. Terre Haute, Indiana CONTENTS PAGE Appreciation ii Introduction ......................... ......... .................................... ...................... iii The Hon. Cordell Hull.......................................................................... 1 Hull Family of Yorkshire, England .................................................. 2 Hull Families of Somersetshire, England ........................................ 54 Hull Families of London, England ........... ........................................ 75 Richard Anderson Hull of New Jer;;ey .......................................... 81 Hull Families of Ireland ...................................................................... 87 Hull-Trowell Lines of Florida ............................................................ 91 William Hu:l Line of Kansas .............................................................. 94 James Hull Family of New Jersey.................................................... 95 William Hull Family of New Foundland ........................................ 97 Hulls Who Have Attained Prominence ............................................ 97 Rev. Wm. E. Hull Myrtle Altus Hull APPRECIATION The writing of this History of the Hull Families in the United States has been a labor of love, moved, we feel, by a justifiable pride in the several family lines whose influence has been a source of strength wherever families bearing -

A Moor Propre: Charles Albert Fechter's Othello

A MOOR PROPRE: CHARLES ALBERT FECHTER'S OTHELLO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Scott Phillips, B.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University •· 1992 Thesis Committee: Approved by Alan Woods Joy Reilly Adviser Department of Theatre swift, light-footed, and strange, with his own dark face in a rage,/ Scorning the time-honoured rules Of the actor's conventional schools,/ Tenderly, thoughtfully, earnestly, FECHTER comes on to the stage. (From "The Three Othellos," Fun 9 Nov. 1861: 76.} Copyright by Matthew Scott Phillips ©1992 J • To My Wife Margaret Freehling Phillips ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express heartfelt appreciation to the members of my thesis committee: to my adviser, Dr. Alan Woods, whose guidance and insight made possible the completion of this thesis, and Dr. Joy Reilly, for whose unflagging encouragement I will be eternally grateful. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable services of the British Library, the Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Theatre Research Institute and its curator, Nena Couch. The support and encouragement given me by my family has been outstanding. I thank my father for raising my spirits when I needed it and my mother, whose selflessness has made the fulfillment of so many of my goals possible, for putting up with me. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Maggie, for her courage, sacrifice and unwavering faith in me. Without her I would not have come this far, and without her I could go no further. -

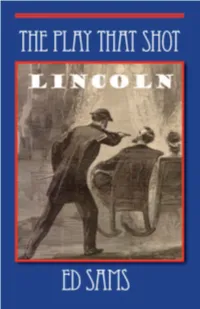

Lincoln Preview Layout 1

The Play that Shot LINCOLN By Ed Sams YELLOW TULIP PRESS WWW.CURIOUSCHAPBOOKS.COM Copyright 2008 by Ed Sams All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief passages in a review. Nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without written permission from the publisher. Published by Yellow Tulip Press PO Box 211 Ben Lomond, CA 95005 www.curiouschapbooks.com America’s Cousin Our American Cousin is a play everyone has heard of but nobody has seen. Once the toast of two continents, the British comedy played to packed houses for years from 1858 to 1865 until that bloody night on April 14, 1865, when John Wilkes Booth made his impromptu appearance on stage during the third act. The matinee idol and national celebrity Booth brought down the house by firing two shots from a lady’s derringer into the back of the head of President Abraham John Wilkes Booth Lincoln. Though the Presidential box hung nearly twelve feet above the stage, Booth at- tempted on a melodramatic leap, and “in his long leap to the stage...the assassin caught his foot in the Treasury Guard flag...and broke his leg” (Redway & Bracken 103). John Wilkes Booth managed to make a successful exit off stage, but his fellow Thespians were not so lucky. Harry Hawk, who played Asa Tren- chard, the American cousin, was still on stage when Booth leapt from the Presidential box. -

The Routledge Companion to African American Theatre and Performance

The Routledge Companion to African American Theatre and Performance Edited by Kathy A. Perkins, Sandra L. Richards, Renée Alexander Craft , and Thomas F. DeFrantz First published 2009 ISBN 13: 978-1-138-72671-0 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-315-19122-5 (ebk) Chapter 20 Being Black on Stage and Screen Black actor training before Black Power and the rise of Stanislavski’s system Monica White Ndounou CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 124 125 Being Black on stage and screen Worth’s Museum, the All- Star Stock Company was the fi rst professional Black stock company and training school for African American performers (Peterson, “Profi les” 70– 71). Cole’s institution challenged popular perceptions of Black performers as “natural actors” 20 lacking intellect and artistry (Ross 239). Notable performers in the company demonstrated expertise in stage management, producing, directing, playwriting, songwriting, and musical composition. They did so while immersed in the study of voice and vocal music (i.e. opera); BEING BLACK ON STAGE movement through dance (i.e. the cakewalk); comedy, including stand-up and ensemble work in specialty acts (i.e. minstrelsy), and character acting. Examples of the performance styles AND SCREEN explored at the All- Star Stock Company include The Creole Show (1890–1897), the Octoroons Company (1895– 1900), the Black Patti Troubadours (1896– 1915), the Williams and Walker Company (1898– 1909), and the Pekin Stock Company (1906– 1911), which performed Black Black actor training before Black Power musicals and popular comedies (Peterson, “Directory” 13). Some of the Pekin’s players were and the rise of Stanislavski’s system also involved in fi lm, like William Foster, who is generally credited as the fi rst Black fi lm- maker ( The Railroad Porter , 1912) (Robinson 168–169). -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

The Hamlet of Edwin Booth Ebook Free Download

THE HAMLET OF EDWIN BOOTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles H Shattuck | 321 pages | 01 Dec 1969 | University of Illinois Press | 9780252000195 | English | Baltimore, United States The Hamlet of Edwin Booth PDF Book Seward, Lincoln's Secretary of State. I mean—. Melania married Donald Trump in to become his third wife. Kennedy and was later inspired by Ronald Reagan. Born as Michelle LaVaughn Robinson, she grew up in a middle-class family and had a conventional upbringing. So exactly as you said, he ran away with her to America, leaving his wife, Adelaide Booth, and his son, Richard, in a mansion in London. Americans are as divided as ever. Because many people held up John Wilkes Booth as a great actor. He would never learn his lines, so in order to generate excitement on stage, he would improvise a lot of physical violence. Booth personally, but I have always had most grateful recollection of his prompt action on my behalf. Her sense of fashion has become a great source of inspiration for many youngsters across the world. Grant, also wrote to Booth to congratulate him on his heroism. He had a volatile emotional life. It was a decision he soon came to regret. Jimmy Carter was the 39th President of America and aspired to establish a government which was both, competent and compassionate. Goff Robert Lincoln. You're right that he was volcanic and that he was like a lightning bolt. Edwin and John Wilkes Booth would have quarrels over more than just politics, as well. Bon Jovi has also released two solo albums. -

Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama James Armstrong The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2317 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FIT FOR THE STAGE: REGENCY ACTORS AND THE INSPIRATION BEHIND ROMANTIC DRAMA by JAMES ARMSTRONG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 ii © 2017 JAMES ARMSTRONG All Rights Reserved iii Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Marvin Carlson Distinguished Professor May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Peter Eckersall Professor ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones Professor ______________________________ Annette J. Saddik Professor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong Adviser: Distinguished Professor Marvin Carlson In this dissertation, I argue that British verse tragedies of the Romantic era must be looked at not as "closet dramas" divorced from the stage, but as performance texts written with specific actors in mind. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

Charlotte Cushman Papers

Charlotte Cushman Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2008 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms008027 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm77017525 Prepared by Audrey Walker Revised and expanded by Margaret McAleer Collection Summary Title: Charlotte Cushman Papers Span Dates: 1823-1941 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1861-1875) ID No.: MSS17525 Creator: Cushman, Charlotte, 1816-1876 Extent: 10,000 items ; 21 containers plus 1 oversize ; 5.5 linear feet ; 1 microfilm reel Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Actress. Correspondence; biographical and genealogical material; annotated scripts and texts of plays, poetry, and readings; newspaper clippings; reviews; and souvenir programs relating chiefly to Cushman's career in the theater. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bellows, Henry W. (Henry Whitney), 1814-1882--Correspondence. Bigelow, John, 1817-1911--Correspondence. Booth, Edwin, 1833-1893--Correspondence. Browning, Elizabeth Barrett, 1806-1861--Correspondence. Carlyle, Jane Welsh, 1801-1866--Correspondence. Chorley, Henry Fothergill, 1808-1872--Correspondence. Crow, Wayman, 1808-1885--Correspondence. Cushman, Charles Augustus, 1818-1896--Correspondence. Cushman, Charlotte, 1816-1876. Cushman, Edwin Charles, 1838- --Correspondence. Cushman, Emma Crow, 1840?- --Correspondence. Cushman, Mary Eliza, 1793-1866--Correspondence. -

Yesterdays with Actors

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/actorsyesterdaOOwinsuoft YESTERDAYS WITH ACTORS. m YESTERDAYS WITH ACTORS BY CATHERINE MARY REIGNOLDS-WINSLOW BOSTON CUPPLES AND COMPANY 1887 Copyright, 1SSC, by Catherine Mary Rrignoi.ds-Winslow. All Rights Reserved. The Hyde Park Press. YESTERDAYS WITH ACTORS BY CA THERINE 1 MAR ' REIGNOLDS- WINSL O W BOSTON CUPPLES AND HURD 94 Boylston Street 1887 Copyright, 1SS6, by Catherine Mary Reignolds-Winslow. All Rights Reserved. The Hyde Park Press. To Helen Morton, M.D., Physician, Faithful Friend, Tnie Woman Good ;t to whose Skill, Constancy, and Courage, I owe Health, Hope, and Inspiration ; these Memories are affectionately inscribed. W&UtAJMf^XLMJWGE&F"' iPIlP C O.N TENTS. PAGE Introduction vii i. Charlotte Cushman 17 2. Edwin Forrest 29 3. _/#/?« Brougham 45 4. Laura Keene — Agnes Robertson ... 62 5. i£. ^4. Sothern 79 6. Ben. De Bar — Matilda Heron —J. H. Hackett — Mrs. John Wood —James E. Murdoch — Mrs. Lander . 100 7. Boston Museum 122 8. Boston Museum, continued 143 9. Travel in America 162 10. Canada and England 184 PHOTO-GRA VURES. PAGE William Warren frontispiece Mrs. Winslow title-page Charlotte Cushman 17 Edwin Forrest 29 John Brougham 45 Laura Keene 62 E. A. Sothern 79 Matilda Heron 108 • VIGNETTES. William E. Burton 62 Agnes Robertson 64 J. A. Smith 84 Mr. Buckstone 90 J. H. Hackett 114 Mrs. John Wood 115 James E. Murdoch 116 E. F. Keach 123 R. M. Field 133 Mr. Barrow 135 Mrs. Barrow - 135 Kate Bateman 136 John Wilkes Booth 140 Mrs. -

Comic Actors and Comic Acting on the 19Th Century American Stage

"Those That Play Your Clowns:" Comic Actors and Comic Acting on the 19th Century American Stage Barnard Hewitt (Barnard Hewitt's Fellows Address was delivered at the ATA Convention in Chicago, August 16, 1977.) It seems to me that critics and historians of theatre have neglected comedians and the acting of comedy, and I ask myself why should this be so? Nearly everyone enjoys the acting of comedy. As the box office has regularly demonstrated, more people enjoy comedy than enjoy serious drama. I suspect that comedy and comedians are neglected because critics and scholars feel, no doubt unconsciously that because they arouse laughter rather than pity and fear, they don't deserve serious study. Whatever the reason for this neglect, it seems to me unjust. In choosing the subject for this paper, I thought I might do something to redress that injustice. I hoped to identify early styles of comic acting on our stage, discover their origins in England, note mutations caused by their new environment, and take note of their evolution into new styles. I don't need to tell you how difficult it is to reconstruct with confidence the acting style of any period before acting was recorded on film. One must depend on what can be learned about representative individuals: about the individual's background, early training and experience, principal roles, what he said about acting and about his roles, pictures of him in character, and reports by his contemporaries - critics and ordinary theatregoers - of what he did and how he spoke. First-hand descriptions of an actor's performance in one or more roles are far and away the most enlightening evidence, but nothing approaching Charles Clarke's detailed description of Edwin Booth's Hamlet is available for an American comic actor.1 Comedians have written little about their art.2 What evidence I found is scattered and ambiguous when it is not contradictory.