Eric J. Plosky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Station Conceptual Engineering Study

Portland Union Station Multimodal Conceptual Engineering Study Submitted to Portland Bureau of Transportation by IBI Group with LTK Engineering June 2009 This study is partially funded by the US Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. IBI GROUP PORtlAND UNION STATION MultIMODAL CONceptuAL ENGINeeRING StuDY IBI Group is a multi-disciplinary consulting organization offering services in four areas of practice: Urban Land, Facilities, Transportation and Systems. We provide services from offices located strategically across the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. JUNE 2009 www.ibigroup.com ii Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................... ES-1 Chapter 1: Introduction .....................................................................................1 Introduction 1 Study Purpose 2 Previous Planning Efforts 2 Study Participants 2 Study Methodology 4 Chapter 2: Existing Conditions .........................................................................6 History and Character 6 Uses and Layout 7 Physical Conditions 9 Neighborhood 10 Transportation Conditions 14 Street Classification 24 Chapter 3: Future Transportation Conditions .................................................25 Introduction 25 Intercity Rail Requirements 26 Freight Railroad Requirements 28 Future Track Utilization at Portland Union Station 29 Terminal Capacity Requirements 31 Penetration of Local Transit into Union Station 37 Transit on Union Station Tracks -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

Pennvolume1.Pdf

PENNSYLVANIA STATION REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I: ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Executive Summary ............................................................... 1 ES.1 Introduction ................................................................ 1 ES.2 Purpose and Need for the Proposed Action ......................................... 2 ES.3 Alternatives Considered ....................................................... 2 ES.4 Environmental Impacts ....................................................... 3 ES.4.1 Rail Transportation .................................................... 3 ES.4.2 Vehicular and Pedestrian Traffic .......................................... 3 ES.4.3 Noise .............................................................. 4 ES.4.4 Vibration ........................................................... 4 ES.4.5 Air Quality .......................................................... 4 ES.4.6 Natural Environment ................................................... 4 ES.4.7 Land Use/Socioeconomics ............................................... 4 ES.4.8 Historic and Archeological Resources ...................................... 4 ES.4.9 Environmental Risk Sites ............................................... 5 ES.4.10 Energy/Utilities ...................................................... 5 ES.5 Conclusion Regarding Environmental Impact ...................................... 5 ES.6 Project Documentation Availability .............................................. 5 Chapter 1: Description -

Attachment a Statement of Work RFQ Number: 6100041691 OVERVIEW: the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (Penndot) Is Respo

Attachment A Statement of Work RFQ Number: 6100041691 OVERVIEW: The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) is responsible for the operating costs for the Amtrak Keystone and Pennsylvanian passenger rail services. The Keystone Service provides frequent higher speed passenger train service along the Amtrak part owned Keystone Corridor between the Harrisburg Transportation Center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. Some trains continue on the Northeast Corridor and terminate at Pennsylvania Station in New York, and the Pennsylvanian runs between New York and Pittsburgh with stops in between. PennDOT aims to increase ridership on these services as increased revenue offsets the state subsidy for the rail services, which is estimated to be $14.9 million in the 2017 Federal fiscal year. In 2012, PennDOT and Amtrak partnered on PA Trips By Train (www.patripsbytrain.com), an initiative spotlighting events and destinations in communities along the service routes. PennDOT is shifting the campaign’s focus from excursion travelers to commuter travel (Keystone) with the goal of gaining more riders. BACKGROUND NEEDED TO COMPLETE WORK PLAN: In 2014, Amtrak conducted surveys of 402 Keystone customers and 400 Pennsylvanian customers. PennDOT is advising interested vendors to obtain the results of those surveys to better understand the project. Information from those surveys, including gender, age, income, and more is available only by executing a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) with Amtrak. Interested contractors must fully complete and sign Attachment E, Amtrak Market Research Data Nondisclosure. The completed hard copy with an original ink signature must be submitted to Amtrak. Interested vendors wishing to have an original returned must submit two signed copies. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMEN ,. JF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Grand Central Terminal AND/OR COMMON Grand Central Terminal LOCATION STREETS,NUMBER 71-105 East 42nd Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New York _ VICINITY OF 18th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York New York 36 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC X2DCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM 2^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _S!TE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _ OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL ^-TRANSPORTATION _NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Pennsylvania Central Transportation Company STREET & NUMBER 466 Lexington Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE New York VICINITY OF New York LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, New York County Hall of Records REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. STREET& NUMBER 31 Chambers Street CITY, TOWN STATE New York New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE New York City Landmarks Commission DATE 1967 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY x_LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE New York New Yn-rlf DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^-ORIGINAL SITE X_GOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE A complete contemporary description would be lengthy—in the brief: "The terminal has two levels. The upper one of these, 20 ft. -

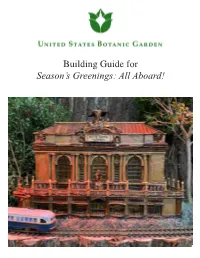

Train Station Models Building Guide 2018

Building Guide for Season’s Greenings: All Aboard! 1 Index of buildings and dioramas Biltmore Depot North Carolina Page 3 Metro-North Cannondale Station Connecticut Page 4 Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal New Jersey Page 5 Chattanooga Train Shed Tennessee Page 6 Cincinnati Union Terminal Ohio Page 7 Citrus Groves Florida Page 8 Dino Depot -- Page 9 East Glacier Park Station Montana Page 10 Ellicott City Station Maryland Page 11 Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad Station Pennsylvania Page 12 Grain Elevator Minnesota Page 13 Grain Fields Kansas Page 14 Grand Canyon Depot Arizona Page 15 Grand Central Terminal New York Page 16 Kirkwood Missouri Pacific Depot Missouri Page 17 Lahaina Station Hawaii Page 18 Los Angeles Union Station California Page 19 Michigan Central Station Michigan Page 20 North Bennington Depot Vermont Page 21 North Pole Village -- Page 22 Peanut Farms Alabama Page 23 Pennsylvania Station (interior) New York Page 24 Pikes Peak Cog Railway Colorado Page 25 Point of Rocks Station Maryland Page 26 Salt Lake City Union Pacific Depot Utah Page 27 Santa Fe Depot California Page 28 Santa Fe Depot Oklahoma Page 29 Union Station Washington Page 30 Union Station D.C. Page 31 Viaduct Hotel Maryland Page 32 Vicksburg Railroad Barge Mississippi Page 33 2 Biltmore Depot Asheville, North Carolina built 1896 Building Materials Roof: pine bark Facade: bark Door: birch bark, willow, saltcedar Windows: willow, saltcedar Corbels: hollowed log Porch tread: cedar Trim: ash bark, willow, eucalyptus, woody pear fruit, bamboo, reed, hickory nut Lettering: grapevine Chimneys: jequitiba fruit, Kielmeyera fruit, Schima fruit, acorn cap credit: Village Wayside Bar & Grille Wayside Village credit: Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, one of the premier architects in American history, the Biltmore Depot was commissioned by George Washington Vanderbilt III. -

Boston-Montreal High Speed Rail Project

Boston to Montreal High- Speed Rail Planning and Feasibility Study Phase I Final Report prepared for Vermont Agency of Transportation New Hampshire Department of Transportation Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas with Cambridge Systematics Fitzgerald and Halliday HNTB, Inc. KKO and Associates April 2003 final report Boston to Montreal High-Speed Rail Planning and Feasibility Study Phase I prepared for Vermont Agency of Transportation New Hampshire Department of Transportation Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Fitzgerald and Halliday HNTB, Inc. KKO and Associates April 2003 Boston to Montreal High-Speed Rail Feasibility Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... ES-1 E.1 Background and Purpose of the Study ............................................................... ES-1 E.2 Study Overview...................................................................................................... ES-1 E.3 Ridership Analysis................................................................................................. ES-8 E.4 Government and Policy Issues............................................................................. ES-12 E.5 Conclusion.............................................................................................................. -

Lancaster Train Station Master Plan Which Is a Product of the Lancaster County Planning Commission and Funded by Pennsylvania Department of Transportation

Lancaster Train Station Master Plan October 2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary of Current and On-Going Station Improvements ......................................................................... 1 Planning Horizons ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Physical Plant ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Maintenance .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Station Capital Improvements ............................................................................................................... 9 Available Non-Transportation Spaces ................................................................................................ 17 Station Artwork ................................................................................................................................... 19 Historic Preservation .......................................................................................................................... -

FOXBOROUGH COMMUTER RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Foxborough Commuter Rail Feasibility Study

FULLTIME FOXBOROUGH COMMUTER RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Foxborough Commuter Rail Feasibility Study FINAL REPORT September 1, 2010 Prepared For: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority With Support From: Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development Prepared By: Jacobs Engineering Group, Boston, MA With: Central Transportation Planning Staff, Boston , MA Anne S. Gailbraith, AICP Barrington, RI 1 REPORT NAME: Foxborough Commuter Rail Feasibility Study PROJECT NUMBER: A92PS03, Task Order No. 2 PREPARED FOR: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) PREPARED BY: Jacobs Engineering Group Anne S. Galbraith Central Transportation Planning Staff (CTPS) DATE: September 1, 2010 FOXBOROUGH COMMUTER RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: IDENTIFY KEY ISSUES AND PROJECT APPROACH .................................................... 13 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Key Issues....................................................................................................................... 17 1.3 Approach ......................................................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 2: ANALYZE THE CAPACITY OF THE EXISTING SYSTEM............................................. -

JONATHAN STURGES HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: the Cottage

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 JONATHAN STURGES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: JONATHAN STURGES HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: The Cottage 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 449 Mill Plain Road Not for publication: City/Town: Fairfield Vicinity: State: CT County: Fairfield Code: 001 Zip Code: 06430 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Buildingfs): X Public-Local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 3 __ buildings ___ sites 1 structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 5 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 JONATHAN STURGES HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

North South Rail Link Feasibility Reassessment Chapters

6. Cost Estimates and Analysis Cost Estimates and Analysis | January 2019 North South Rail Link Feasibility Reassessment Final Report 101 Photo Source: Charlotte / Unsplash 102 North South Rail Link Feasibility Reassessment Final Report January 2019 | Cost Estimates and Analysis 6. Cost Estimates and Analysis 6.1 Cost Estimating Methodology Estimates for the NSRL project follow industry best • The cost analyses were performed in conjunction practices for large public transportation programs. with the engineering and design process, and The estimates are classifed in accordance with are based on the information available for each the Association for the Advancement of Cost alignment, as well as key constructability issues Engineering International (AACEi) Estimate identifed by the project team. Classifcation System. The System characterizes • Research was conducted to determine compa- the level of design and of construction detail and rable projects to NSRL. Individual benchmarking establishes the appropriate ranges of contingency exercises were developed for key engineering corresponding to these levels of detail. and construction components (e.g., tunnel and station excavations). Refer to Appendix E for The cost estimates within this report are not further details on the estimating methodology. intended to set the fnal budget for the proposed project, but to allow for comparison of the Defnitions of the terms used in this chapter, alignments. The following parameters and guidance such as indirect costs, additional costs, and soft form the basis for the cost estimate: costs, can be found in Appendix E under the Cost Methodology section. • All costs are reported in 2018 US dollars and es- calated to Quarter 1, 2028, the year that has been estimated as the midpoint of project construc- tion.