Promoting Urban Teachers' Understanding of Technology, Content, and Pedagogy in the Context of Case Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

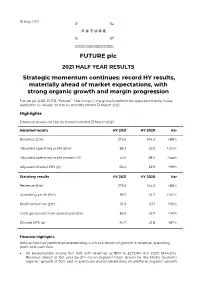

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs

Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs March 2016 Independent Statistics & Analysis U.S. Department of Energy www.eia.gov Washington, DC 20585 This report was prepared by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the statistical and analytical agency within the U.S. Department of Energy. By law, EIA’s data, analyses, and forecasts are independent of approval by any other officer or employee of the United States Government. The views in this report therefore should not be construed as representing those of the Department of Energy or other federal agencies. U.S. Energy Information Administration | Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs i March 2016 Contents Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Onshore costs .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Offshore costs .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Approach .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Appendix ‐ IHS Oil and Gas Upstream Cost Study (Commission by EIA) ................................................. 7 I. Introduction……………..………………….……………………….…………………..……………………….. IHS‐3 II. Summary of Results and Conclusions – Onshore Basins/Plays…..………………..…….… -

The Future of U.S. Commercial Imagery VISION IMPLEMENTATION

» INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION » NEW CONCERNS ABOUT PRIVACY SUMMER 2012 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE UNITED STATES GEOSPATIAL INTELLIGENCE FOUNDATION Crossroads The Future of U.S. Commercial Imagery VISION IMPLEMENTATION At L-3 STRATIS, we help organizations make the technological and cultural changes needed to implement their vision. Our innovative cyber, intel and next generation IT solutions enable your mission, while reducing costs and improving the user experience. Find out more. Contact [email protected] or visit www.L3STRATIS.com STRATIS L-3com.com contents summer 2012 2 | VANTAGE POINT Features 27 | MEMBERSHIP PULSE Introducing the new Accenture upgrades to USGIF strategic partner. trajectory magazine. 9 | AT A CROSSROADS 4 | INTSIDER Proposed cuts to NGA’s EnhancedView 28 | GEN YPG News updates plus high- program revive the commercial Beacon of Hope and YPG lights from got geoint? imagery debate. work together to help By Kristin Quinn rebuild New Orleans. 6 | IN MOTION Small Business Advisory 30 | HORIZONS Working Group hosts Reading List, Peer Intel, 16 | THE $4B GLOBAL PIE luncheon with guest Calendar. speakers from NGA. New competition is forming in the commercial data marketplace. 32 | APERTURE 8 | ELEVATE By Brad Causey Canada has it. Germany Mizzou’s Center for has it. Italy has it. Back in Geospatial Intelligence the U.S., SAR? goes beyond academics. 22 | PIGEONHOLED Privacy policies threaten advances ON THE COVER Cover image of Dallas, Texas, in technology. courtesy of GeoEye. Image has By Jim Hodges been altered with permission for editorial purposes. trAJectorYmAGAZIne.com eXcLusIVes VIDEO PODCAST PANEL “What can you do with Exclusive interview Recap of the Space geography?” National with Kevin Pomfret, Enterprise Council's Geographic video director of the Centre panel on the impor- featuring Keith for Spatial Law and tance of commercial Masback of USGIF. -

Future of Defense Task Force Report 2020 Cover Photo Credit: NASA Future of Defense Task Force

draft Future of Defense Task Force Report 2020 Cover photo credit: NASA Future of Defense Task Force FUTURE OF DEFENSE TASK FORCE September 23, 2020 The Honorable Adam Smith Chairman House Armed Services Committee 2216 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable William “Mac” Thornberry Ranking Member House Armed Services Committee 2216 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Chairman Smith and Ranking Member Thornberry: Thank you for your support in standing up the Future of Defense Task Force. We are pleased to present you with our final report. Sincerely, Seth Moulton Jim Banks Chair Chair Future of Defense Task Force Future of Defense Task Force Susan Davis Scott DesJarlais Member of Congress Member of Congress Chrissy Houlahan Paul Mitchell Member of Congress Member of Congress Elissa Slotkin Michael Waltz Member of Congress Member of Congress Future of Defense Task Force Table of Contents PROLOGUE ............................................................................................... 1 TASK FORCE MEMBERS ........................................................................ 3 FINDINGS .................................................................................................. 5 RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................... 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... 13 EVIDENCE .............................................................................................. 21 EMERGING -

Loudoun County Public Schools

LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS & FINANCIAL SERVICES PROCUREMENT AND RISK MANGEMENT DIVISION 21000 Education Court, Suite #301 Ashburn, VA 20148 Phone (571) 252-1270 Fax (571) 252-1432 July 1, 2021 Contract Information Title: Magazine and Periodical Subscription Service IFB/RFP Number: IFB #I21332 Supersedes: IFB #I17142 Vendor Name: Debarment Form: Required: No Form on File: Not Applicable Contractor Certification: Required: No Form on File: Not Applicable Virginia Code 22.1-296.1 …the school board shall require the contractor to provide certification that all persons who will provide such services have not been convicted of a felony or any offense involving the sexual molestation or physical or sexual abuse or rape of a child. Pricing: See attached Pricing Sheet(s) Contract Period: July 1, 2021 – June 30, 2022 Contract Renewal New Number: Number of Renewals 4 Remaining: Procurement Contact: Pixie Calderwood Procurement Director: Andrea Philyaw LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS & FINANCIAL SERVICES PROCUREMENT AND RISK MANAGEMENT SERVICES 21000 Education Court, Suite #301 Ashburn, VA 20148 Phone (571) 252-1270 Fax (571) 252-1432 June 28, 2021 NOTICE OF AWARD IFB #I21332 Magazine and Periodical Subscription Services Loudoun County Public Schools is awarding IFB #I21332 Magazine and Periodical Subscription Services to EBSCO Information Services of Birmingham, AL. We appreciate your interest in being of service to the Loudoun County Public Schools. Andrea Philyaw Procurement Director LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS IFB #I21332 MAGAZINES AND PERIODICALS SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE Package 1: Library Office Print & Online Line Awarded UoM Title Name Format Publisher Name ISSN # Item Price 1EAComputers in Libraries Print Information Today, Inc. -

Alternatives for Future U.S. Space-Launch Capabilities Pub

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE A CBO STUDY OCTOBER 2006 Alternatives for Future U.S. Space-Launch Capabilities Pub. No. 2568 A CBO STUDY Alternatives for Future U.S. Space-Launch Capabilities October 2006 The Congress of the United States O Congressional Budget Office Note Unless otherwise indicated, all years referred to in this study are federal fiscal years, and all dollar amounts are expressed in 2006 dollars of budget authority. Preface Currently available launch vehicles have the capacity to lift payloads into low earth orbit that weigh up to about 25 metric tons, which is the requirement for almost all of the commercial and governmental payloads expected to be launched into orbit over the next 10 to 15 years. However, the launch vehicles needed to support the return of humans to the moon, which has been called for under the Bush Administration’s Vision for Space Exploration, may be required to lift payloads into orbit that weigh in excess of 100 metric tons and, as a result, may constitute a unique demand for launch services. What alternatives might be pursued to develop and procure the type of launch vehicles neces- sary for conducting manned lunar missions, and how much would those alternatives cost? This Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study—prepared at the request of the Ranking Member of the House Budget Committee—examines those questions. The analysis presents six alternative programs for developing launchers and estimates their costs under the assump- tion that manned lunar missions will commence in either 2018 or 2020. In keeping with CBO’s mandate to provide impartial analysis, the study makes no recommendations. -

The Future of the Drone Economy

The Future of the Drone Economy A comprehensive analysis of the economic potential, market opportunities, and strategic considerations in the drone economy A Report From Levitate Capital 1 Disclaimer The information contained herein is intended for general informational purposes only, does not take into account the reader’s specific circumstances, and may not reflect the latest developments. Certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources, which although believed to be accurate, has not been independently verified by Levitate Capital. Further, certain information (including forward-looking statements and economic and market information) has been obtained from published sources and/or prepared by third parties and in certain cases has not been updated through the date hereof. While such sources are believed to be reliable, Levitate Capital does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Levitate Capital does not undertake any obligation to update the information contained herein as of any future date. Levitate Capital LLC disclaims, to the fullest extent, any liability for the accuracy and completeness of the information in this document and for any acts and omissions made on such information. Levitate Capital has invested in a few companies mentioned in this paper, including but not limited to: Dedrone, Elroy Air, Matternet, Shield AI, Skydio, Skyports, and Volocopter. 2 Executive Summary $ Billions 90 40 15 2020 2025 2030 Global Market Fastest Growth The global drone Enterprise will economy will grow remain the fastest from $15B to $90B growing segment by 2030 until 2025. Logistics will become the fastest after 2025 Largest Segment Largest Region Defense will Asia-Pacific will remain the largest remain the largest segment until non-defense 2024. -

State of the Space Industrial Base 2020 Report

STATE OF THE SPACE INDUSTRIAL BASE 2020 A Time for Action to Sustain US Economic & Military Leadership in Space Summary Report by: Brigadier General Steven J. Butow, Defense Innovation Unit Dr. Thomas Cooley, Air Force Research Laboratory Colonel Eric Felt, Air Force Research Laboratory Dr. Joel B. Mozer, United States Space Force July 2020 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this report reflect those of the workshop attendees, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US government, the Department of Defense, the US Air Force, or the US Space Force. Use of NASA photos in this report does not state or imply the endorsement by NASA or by any NASA employee of a commercial product, service, or activity. USSF-DIU-AFRL | July 2020 i ABOUT THE AUTHORS Brigadier General Steven J. Butow, USAF Colonel Eric Felt, USAF Brig. Gen. Butow is the Director of the Space Portfolio at Col. Felt is the Director of the Air Force Research the Defense Innovation Unit. Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate. Dr. Thomas Cooley Dr. Joel B. Mozer Dr. Cooley is the Chief Scientist of the Air Force Research Dr. Mozer is the Chief Scientist at the US Space Force. Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FROM THE EDITORS Dr. David A. Hardy & Peter Garretson The authors wish to express their deep gratitude and appreciation to New Space New Mexico for hosting the State of the Space Industrial Base 2020 Virtual Solutions Workshop; and to all the attendees, especially those from the commercial space sector, who spent valuable time under COVID-19 shelter-in-place restrictions contributing their observations and insights to each of the six working groups. -

Future Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2014

2014 Future plc Annual Report and Accounts 01 Future plc Group overview Future plc is an international media group and leading digital publisher, listed on the London Stock Exchange (symbol: FUTR). These highlights refer to the Group’s annual results for the year ended 30 September 2014. Strategic Report Continuing Revenue Net Cash 01 Group overview 02 Chairman’s statement 03 Chief Executive’s review £66.0m £ 7. 5 m 05 Business model 2013: £82.6m 2013: Net Debt £(6.9)m 07 What we do 08 Business review 09 Risks and uncertainties 11 Corporate responsibility Continuing EBITDAE Continuing Loss before tax Financial Review £(7.0)m £(35.4)m 13 Financial review 2013: £(0.6)m 2013: £(2.2)m Corporate Governance Continuing EBITE Continuing Exceptional items 17 Board of Directors 19 Directors’ report 23 Corporate Governance report 29 Directors’ remuneration report £(10.3)m £(24.3)m 41 Independent auditors’ report 2013: £(3.4)m 2013: £2.6m Financial Statements Continuing Digital Advertising Continuing Users 45 Financial statements 82 Notice of Annual General Meeting 87 Investor information 66% 57m of total advertising revenues (2013: 61%) a month (+10% year-on-year) EBITDAE represents EBITE represents Exceptional items for earnings before interest, earnings before 2014 above includes tax, depreciation, interest, tax, impairment impairment of intangible amortisation, impairment and exceptional items. assets of £16.8m. and exceptional items. Annual Report and Accounts 2014 02 Strategic Report Chairman’s statement Transformational Year This has been a year of signifi cant change for Future and the fi nancial results in 2014 do not refl ect the transformational activity that has been implemented. -

How Can We Accelerate the Insertion of Leading-Edge Technologies Into Our Military Weapons Systems?

How Can We Accelerate the Insertion of Leading-Edge Technologies Into Our Military Weapons Systems? Naval Postgraduate CRUSER Workshop April 5, 2021 George Galdorisi (Captain- U.S. Navy retired) Naval Information Warfare Center, Pacific Dr. Sam Tangredi (Captain U.S. Navy – retired) U.S. Naval War College 1 How Can We Accelerate the Insertion of Leading-Edge Technologies Into Our Military Weapons Systems? Executive Summary At the highest levels of U.S. intelligence and military policy documents, there is universal agreement that the United States remains at war, even as the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan wind down. As the cost of capital platforms—especially ships and aircraft—continues to rise, the Department of Defense is increasingly looking to procure comparatively inexpensive systems as important assets to supplement the Joint Force. As the United States builds a force structure to contend with high-end threats, it has introduced a “Third Offset Strategy” to find ways to gain an asymmetric advantage over potential adversaries. One of the key technologies embraced by this strategy is that of unmanned systems. Both the DoD and the DoN envision a future force with large numbers of relatively inexpensive unmanned systems complementing manned platforms. The U.S. military’s use of these systems—especially armed unmanned systems—is not only changing the face of modern warfare, but is also altering the process of decision-making in combat operations. These systems are evolving rapidly to deliver enhanced capability to the warfighter and seemed poised to deliver the next “revolution in military affairs.” Big data, artificial intelligence and machine learning represent some of the most cutting-edge technologies today, and will likely be the dominant technologies for the next several decades and beyond. -

Future Plc Capital Markets Day 14Th February 2019 Agenda

Future plc Capital Markets Day 14th February 2019 Agenda 3pm Business overview & growth strategy | Zillah Byng-Thorne 3.10pm Owning a vertical - the value of leadership Vertical strategy | Aaron Asadi Audience & SEO | Sam Robson Tom’s Guide | Mark Spoonauer 3.40pm Coffee break 3.55pm The US media market & eCommerce | Michael Kisseberth Peak trading | Jason Kemp 4.20pm Future tech and the power of RAMP Evolution of our tech stack | Kevin Li Ying Ad tech | Zack Sullivan | Reda Guermas 4.45pm Investment thesis | Penny Ladkin-Brand 4.55pm Conclusion & questions | Zillah Byng-Thorne Drinks 2 Today’s speakers Vertical US Market & eCommerce Technology & Ads Zillah Byng- Aaron Asadi Michael Kisseberth Zack Sullivan Thorne Chief Content Chief Revenue SVP Sales & Chief Executive Officer Officer Operations, UK Zillah will be talking Aaron will be talking Mike will be talking Zack will be talking about how Future about the benefits of about the dynamics of about the nature of operates and our our vertical strategy the US media market programmatic growth strategy and opportunities advertising and how within eCommerce we win in this market Penny Ladkin- Sam Robson Jason Kemp Reda Guermas Brand Audience Director eCommerce VP Software Chief Financial Director Engineering Ad Tech Officer Sam will be covering how we succeed Jason will be talking Reda will be talking through search and about how we Penny will be talking about the science the value of vertical capitalise on peak about how we behind our ad tech leadership trading times succeed through stack -

Hyundai and the Walking Dead Creator/Writer Robert Kirkman Unveil Zombie Survival Machine at ComicCon

Hyundai Motor America 10550 Talbert Ave, Fountain Valley, CA 92708 MEDIA WEBSITE: HyundaiNews.com CORPORATE WEBSITE: HyundaiUSA.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HYUNDAI AND THE WALKING DEAD CREATOR/WRITER ROBERT KIRKMAN UNVEIL ZOMBIE SURVIVAL MACHINE AT COMICCON ID: 36672 COSTA MESA, Calif., July 12, 2012 – Much to the dismay of zombies around the world, a Zombie Survival Machine was unveiled last night at San Diego’s ComicCon. The customized Hyundai Elantra Coupe Zombie Survival Machine, designed by The Walking Dead creator/writer Robert Kirkman and fabricated by Design Craft, was revealed on the ComicCon floor at the Future US booth. Hyundai’s Zombie Survival Machine showcases modifications including: a frontend custom zombie plow with spikes, armored window coverings, a roof hatch to allow passengers to fend off attacking walkers, a trunk full of electric and pneumatic weaponry, front and back end floodlights, spiked allterrain/rally type tires, a CB radio system and much more. Fans can view a series of behindthescenes videos that detail the creation of the Zombie Survival Machine and showcase the car build from start to finish at HyundaiUndead.com and on Skybound.com “Our custom Elantra Coupe Zombie Survival Machine is the ultimate car for The Walking Dead fans and anyone who wants to survive a zombie invasion,” said Steve Shannon, vice president of Marketing, Hyundai Motor America. “We are excited for fans to come and experience the Elantra Coupe and GT in a unique, postapocalyptic way.” The Hyundai Undead program celebrates the release of the 100th issue of The Walking Dead comic.