A New Wine Tasting Approach Based on Emotional Responses to Rapidly Recognize Classic European Wine Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dessert Wines 1

Dessert Wines 1 AMERICA 7269 Macari 2002 Block E, North Fork, Dessert Wines Long Island tenth 75.00 1158 Mayacamas 1984 Zinfandel Late Harvest 50.00 (2oz pour) 7218 Robert Mondavi 1998 Sauvignon Blanc 27029 Kendall-Jackson Late Harvest Chardonnay 7.50 Botrytis, Napa tenth 100.00 26685 Château Ste. Michelle Reisling 7257 Robert Mondavi 2014 Moscato D’Oro, Late Harvest Select 8.00 Napa 500ml 35.00 26792 Garagiste, ‘Harry’ Tupelo Honey Mead, 6926 Rosenblum Cellars Désirée Finished with Bern’s Coffee Blend 12.00 Chocolate Dessert Wine tenth 45.00 27328 Ferrari Carano Eldorado Noir Black Muscat 13.00 5194 Silverado Vineyards ‘Limited Reserve’ 26325 Dolce Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc Late Harvest 115.00 by Far Niente, Napa 19.00 7313 Steele 1997 ‘Select’ Chardonnay 27203 Joseph Phelps ‘Delice’ Scheurebe, St Helena 22.50 Late Harvest, Sangiacomo Vineyard tenth 65.00 6925 Tablas Creek 2007 Vin De Paille, Sacerouge, Paso Robles tenth 105.00 - Bottle - 7258 Ca’Togni 2009 Sweet Red Wine 7066 Beringer 1998 Nightingale, Napa tenth 65.00 by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 99.00 7289 Château M 1991 Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc 7090 Ca’Togni 2003 Sweet Red Wine by Monticello, Napa tenth 65.00 by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 150.00 6685 Château Ste. Michelle Reisling 7330 Ca’Togni 2001 Sweet Red Wine Late Harvest Select by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 150.00 7081 Château St. Jean 1988 Johannisberg Riesling, 6944 Ca’Togni 1999 Sweet Red Wine Late Harvest, Alexander Valley tenth 85.00 by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 105.00 7134 Ca’Togni 1995 Sweet Red Wine 6325 Dolce 2013 Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 125.00 by Far Niente, Napa tenth 113.00 27328 Ferrari Carano Eldorado Noir Black Muscat 13.00 7000 Elk Cove Vineyard Ultima Riesling, 15.5% Residual Sugar, Willamette tenth 80.00 6777 Eroica 2000, Single Berry Select Riesling, by Chateau Ste. -

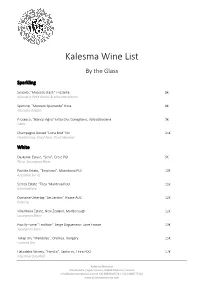

Kalesma Wine List

Kalesma Wine List By the Glass Sparkling Solicelo, “Moscato d’asti“ Frizzante 8€ Muscat A Petit Grains & Moscato Bianco Sperone, “Moscato Spumante” Rose 8€ Moscato Rosato Prosecco, “Bianca Vigna“ Extra Dry, Conegliano, Valdobbiadene 9€ Glera Champagne Gosset “Extra Brut” NV 25€ Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier White Daskalaki Estate, “Sera”, Crete PGI 9€ Plyto, Sauvignon Blanc Pavlidis Estate, “Emphasis”, Macedonia PGI 10€ Assyrtiko Sur lie Semeli Estate “Thea “Mantinia PDO 11€ Moschofilero Domaine Ostertag “Les Jardins” Alsace AOC 12€ Riesling Villa Maria Estate, New Zealand, Marlborough 12€ Sauvignon Blanc Pouilly-Fume “Tradition” Serge Dagueneau- Loire France 13€ Sauvignon Blanc Tokaji Dry “Mandolas”, Oremus, Hungary 15€ Furmint Dry Hatzidakis Winery, “Familia”, Santorini, Thira PDO 17€ Assyrtiko Unoaked Kalesma Mykonos Aleomandra / Agios Ioannis, 84600 Mykonos, Greece [email protected] ● +30 6983918726 / +30 22890 77222 www.kalesmamykonos.com Rose Domaine Skouras, “Peplo”, PDO Peloponnese 11€ Syrah Sur lie, Acacia aged Agiorgitiko, Amphora aged Mavrophilero Château Miraval, Miraval Studio, AOC Côtes de Provence 13€ Cinsault, Grenache, Rolle, Tibouren Château Val Joanis, “Tradition Rose”, AOP Luberon 14€ Syrah, Grenache Red Domaine Karydas, “Naoussa”, PDO Naoussa, Greece 12€ Oaked Xinomavro Pavlidis Estate, “Emphasis”, PGI Drama, Greece 14€ Oak aged Syrah Parparousis Estate, “Nemea Reserve”, PDO Nemea, Greece 15€ Oak aged Agiorgitiko Dessert Hatzidakis Winery, Vinsanto 16 years old, PDO Santorini 20€ Oak aged Assyrtiko, -

27 CFR Ch. I (4–1–17 Edition)

§ 4.92 27 CFR Ch. I (4–1–17 Edition) Peloursin Suwannee Petit Bouschet Sylvaner Petit Manseng Symphony Petit Verdot Syrah (Shiraz) Petite Sirah (Durif) Swenson Red Peverella Tannat Picpoul (Piquepoul blanc) Tarheel Pinotage Taylor Pinot blanc Tempranillo (Valdepen˜ as) Pinot Grigio (Pinot gris) Teroldego Pinot gris (Pinot Grigio) Thomas Pinot Meunier (Meunier) Thompson Seedless (Sultanina) Pinot noir Tinta Madeira Piquepoul blanc (Picpoul) Tinto ca˜ o Prairie Star Tocai Friulano Precoce de Malingre Topsail Pride Touriga Primitivo Traminer Princess Traminette Rayon d’Or Trebbiano (Ugni blanc) Ravat 34 Trousseau Ravat 51 (Vignoles) Trousseau gris Ravat noir Ugni blanc (Trebbiano) Redgate Valdepen˜ as (Tempranillo) Refosco (Mondeuse) Valdiguie´ Regale Valerien Reliance Valiant Riesling (White Riesling) Valvin Muscat Rkatsiteli (Rkatziteli) Van Buren Rkatziteli (Rkatsiteli) Veeblanc Roanoke Veltliner Rondinella Ventura Rosette Verdelet Roucaneuf Verdelho Rougeon Vergennes Roussanne Vermentino Royalty Vidal blanc Rubired Vignoles (Ravat 51) Ruby Cabernet Villard blanc St. Croix Villard noir St. Laurent Vincent St. Pepin Viognier St. Vincent Vivant Sabrevois Welsch Rizling Sagrantino Watergate Saint Macaire Welder Salem White Riesling (Riesling) Salvador Wine King Sangiovese Yuga Sauvignon blanc (Fume´ blanc) Zinfandel Sauvignon gris Zinthiana Scarlet Zweigelt Scheurebe [T.D. ATF–370, 61 FR 539, Jan. 8, 1996, as Se´millon amended by T.D. ATF–417, 64 FR 49388, Sept. Sereksiya 13, 1999; T.D. ATF–433, 65 FR 78096, Dec. 14, Seyval (Seyval blanc) 2000; T.D. ATF–466, 66 FR 49280, Sept. 27, 2001; Seyval blanc (Seyval) T.D. ATF–475, 67 FR 11918, Mar. 18, 2002; T.D. Shiraz (Syrah) ATF–481, 67 FR 56481, Sept. 4, 2002; T.D. -

Sparkling Wines by the Bottle

House Wines: 250 ml 0.5 l 1.0 l White Wines: Sauvignon Blanc (South Africa) 8,50 16 30 Chardonnay (Chile) 7 13 24 Pinot Grigio (Italy) 8,50 16 30 Sauvignon/Semillon/Muscadelle Blend (France) 8,50 16 30 Red Wines: Merlot (Chile) 7 13 24 Cabernet Sauvignon (Chile) 7 13 24 Pinot Noir (California) 8,50 16 30 Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon Blend (France) 8,50 16 30 Rose Wines: White Zinfandel - Rose (California) 7 Sparkling Wines by the Bottle HENKEL (dry), - Piccolo (Germany) 9,50 CONCHA Y TORO (Chile) 25 PINK, Brut Rose (Australia) 28 GRAHAM BECK BRUT (South Africa) 38 GRAHAM BECK ROSE, Brut (South Africa) 42 CHANDON (dry), Brut (California) 45 All prices are subject to a 15% Service Charge *As of January 1st, 2015 7.5% VAT will be added to all items* Champagne by the Bottle MOET & CHANDON IMPERIAL, Half Bottle (France) 42,50 MOET & CHANDON IMPERIAL (France) 85 VEUVE CLIQUOT, Ponsardin Brut (France) 95 White Wines: BOURGOGNE FLEURS DE PRINTEMPS, 2011/2012(France) 1/2 Bottle or Full Bottle 19/38 100% Chardonnay from the Chablis district, authentic granny smith apple flavour, great balance, and long crystal clear finish. CHATEAU CANTELAUDETTE, Graves de Vayres 2009 (France) 29 A blend of Sauvignon/Semillon and Muscadelle grapes, smooth structure with a round and delicate body. Aromas of passion fruit and citrus. RAYUN, Chardonnay 2009 (Chile) 29 Fresh and clean scent. Attractively juicy mouthful with melon and banana. NOBILIS VINHO VERDE, 2012 (Portugal) 32 Soft, light refreshing blended white with a slight fizz enhancing it’s bouquet and freshness. -

BULL White Wine

Sparkling ROSÉ OF GARNACHA, MOURVEDRE • Azimut 'Brut Nature' Penedes, Catalonia, SP 45 MOLETTE, ALTESSE • Lambert de Seyssel 'Petit Royal' Savoie, France NV 45 CHARDONNAY BLEND • Copinet Champagne 'Caractére Rosé' Marne Valley half 45 full 85 CHARDONNAY • Larmandier Champagne Cramant Grand Cru half 58 full 109 REISLING • Peter Lauer 'Sekt Reserve' Saar, DE '92 155 Rosé GRENACHE, CINSAULT, SYRAH & TIBOUREN • Le Mesclances, Provence '20 35 HONDARIBBI ZURI & BELTZA • Ameztoi 'Rubentis' Getariajo, Txakolina, SP '20 45 TIBOUREN, GRENACHE • Clos Cibonne, Cuvée Spéciale , Cotes de Provence '20 59 Î ZIN., TROUSSEAU GRIS • Broc Cellars ‘White Zin’ Sonoma + Russian River, CA ‘19 59 MOURVEDRE, CINSAULT, GRENACHE • Tempier Bandol 'Rose', Provence '20 109 TIBOUREN, GRENACHE • Clos Cibonne 'Cuvee Marius' Provence, France '17 119 White Wines BURGUNDY + BEAUJOLAIS CHARDONNAY • Jean-Paul Brun 'Terres Dorees' Beaujolais 45 CHARDONNAY • Thevenet & Fils, Pierreclos '19 45 CHARDONNAY • Vincent Mothe, Chablis '18 65 ALIGOTE • Alice & Olivier De Moor, Courgis '17 65 CHARDONNAY • Simone Bize & Fils 'Savigny Les Beaune '18 119 CHARDONNAY • Domaine Rollin Pere & Fils, Grand Cru, Corton-Charlemagne '13 229 JURA, SAVOIE, ALSACE JACQUERE • A. & M. Quenard 'Les Abymes' Savoie' '20 45 Î CHARDONNAY, SAVIGNIN • Domaine de Montbourgeau 'L’Etoile' Jura '14 59 Î CHARDONNAY • Domaine Overnoy-Crinquand 'Arbois-Pupillin' Jura '15 59 JACQUERE • Maison des Ardoisieres, 'Silice' Savoie '18 59 REISLING • Domaine Ostertag 'Vignoble d'E' Alsace '15 64 Î SAVIGNIN • Domaine du Pelican -

Fremont Wine & Booze Menu

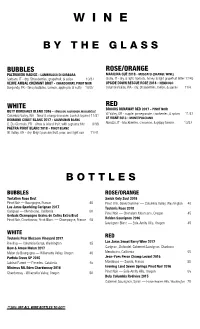

W I N E B Y T H E G L A S S BUBBLES ROSE/ORANGE PALTRINIERI RADICE - LAMBRUSCO DI SORBARA MARILINA CUÈ 2018 - MOSCATO (ORANGE WINE) Sorbara, IT - dry. Strawberries, grapefruit, & spice 10/37 Sicilia, IT - dry, & light. Apricots, honey, & light grapefruit bitter 12/45 VEUVE AMBAL CREMANT BRUT - CHARDONNAY, PINOT NOIR UPSIDE DOWN RESCUE ROSE 2018 - NEBBIOLO Burgundy, FR - fancy bubbles. Lemon, apple pie, & nutty 10/37 Columbia Valley, WA - dry. Strawberries, melon, & apples 11/4 RED WHITE BROOKS RUNAWAY RED 2017 - PINOT NOIR BUTY BORDEAUX BLEND 2016 - SEMILLON, SAUVIGNON, MUSCADELLE W. Valley, OR - supple, pomegranate, cranberries, & spices 11/41 Columbia Valley, WA - floral & orange blossom. Lush & layered 11/41 LE VIGNE 2013 - MONTEPULCIANO DOMAINE COUET BLANC 2017 - SAUVIGNON BLANC C. Du Giennois, FR - citrus & island fruit, with a grassy bite 9/33 Abruzzo, IT - blackberries, cinnamon, & grippy tannins 10/37 PAETRA PINOT BLANC 2018 - PINOT BLANC W. Valley, OR - dry. Bright passion fruit, pear, and light oak 11/41 B O T T L E S BUBBLES ROSE/ORANGE Tentation Rose Brut Swick Only Zuul 2018 Pinot Noir — Bourgogne, France 40 Pinot Gris, Gewurtraminer — Columbia Valley, Washington 40 Las Jaras Sparkling Carignan 2017 Teutonic Rose 2018 Carignan — Mendocino, California 60 Pinot Noir — Chehalem Mountains, Oregon 45 Gerbais Champagne Grains de Celles Extra Brut Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc — Champagne, France 65 Holden Sauvignon 2016 Sauvignon Blanc — Eola-Amity Hills, Oregon 45 WHITE Teutonic Pear Blossom Vineyard 2017 RED Riesling — Columbia Gorge, Washington 35 Las Jaras Sweet Berry Wine 2017 Bow & Arrow Melon 2017 Carignan, Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon, Charbono Melon de Bourgogne — Willamette Valley, Oregon 40 Mendocino, California 55 Partida Creus SP 2015 Jean-Yves Peron Champ Levant 2016 Subirat Parent — Penedes, Catalonia 45 Mondeuse — Savoie, France 55 Minimus Mt. -

CHAMBERS ROSEWOOD NV MUSCADELLE Review Summary

CHAMBERS ROSEWOOD NV MUSCADELLE Review Summary 91 pts/SPECIAL VALUE “Among the benchmarks for fortified wine in Australia with a fabled few, this is a younger average base with a smidgeon of barrel work amidst a pantheon of highly complex wines. None the worst for it, equipping the wine with a versatile drinkability at the table. Malty. Very. The sweetness belied by a je ne sais quoi freshness. Otherwise orange blossom, truffled honey and creme brûlee. I would drink this chilled.” Ned Goodwin, Halliday Wine Companion August 6, 2020 94 pts “Bright, clear golden orange; apart from the bizarrely low price, the fortifying spirit has been so cleverly chosen and then integrated, you can sail past it without noticing its presence. I really shouldn't go praising this wine too highly, even less suggest it's a classy way of getting smashed.” James Halliday, Halliday Wine Companion 2020 90 pts “A luscious, amber-hued sticky from the spiritual home of dessert wines down under, Rutherglen, this wine oozes chocolate, caramel, mint, coffee and that old library smell that emanates from so many fortifieds. The palate is ultrarich and satin-textured with molassesy sweetness. The alcohol feels a little hot and it could use a bit more acidity, but this is nevertheless an affordable and indulgent drop.” Christina Pickard, Wine Enthusiast February 2019 93 pts “Bright, clear golden orange hue. Even though very young, its time in oak has added some complexity to the wanton display of malt, butterscotch, cold tea, nuts and spices. It is lusciously sweet, of course, yet leaves the mouth fresh. -

Stella Maris Resort Club

Resort Club Wine List House Wines 250 ml 0.5 l 1.0 l White Wines Sauvignon Blanc (Chile) 9 17 32 Chardonnay (Chile) 9 17 32 Pinot Grigio (Italy) 9 17 32 Red Wines Merlot (Chile) 9 17 32 Cabernet Sauvignon (Chile) 9 17 32 Pinot Noir (California) 9 17 32 Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon Blend (France) 9 17 32 Rose Wines White Zinfandel - Rose (California) 9 Sparkling Wines by the Bottle Henkel (dry), - Piccolo (Germany) 10,50 Concha Y Toro (Chile) 25 Pink, Brut Rose (Australia) 28 Graham Beck Brut (South Africa) 38 Graham Beck Rose, Brut (South Africa) 42 Chandon (dry), Brut (California) 45 Champagne by the Bottle Moet & Chandon Imperial (France) 90 Veuve Cliquot, Ponsardin Brut (France) 95 All prices are subject to a 15% Service Charge & 7.5% VAT White Wines Bourgogne Fleurs De Printemps, 2011/2012(France) 1/2 Bottle or Full Bottle 19/38 100% Chardonnay from the Chablis district, authentic granny smith apple flavour, great balance, and long crystal clear finish. Chateau Cantelaudette, Graves de Vayres 2011 (France) 29 A blend of Sauvignon/Semillon and Muscadelle grapes, smooth structure with a round and delicate body. Aromas of passion fruit and citrus. Nobilis Vinho Verde, 2012 (Portugal) 32 Soft, light refreshing blended white with a slight fizz enhancing it’s bouquet and freshness. Dr. Heidemanns-Bergweiler Riesling,2013 (Germany) 38 A fruit-driven easy to drink style that refreshes the palate. Kudos, Pinot Gris, 2013 (Oregon) 38 Crisp, light bodied full of pear, banana and spice notes with a vibrant long finish. Sauvignon Blanc Reserve, Fruits d'ete 2013 (France) 48 Hints of tropical fruit like papaya and mango, a lingering smooth finish on the palate. -

LA ROSE SARRON (France, Bordeaux, Saint Pierre De Mons)

LA ROSE SARRON (France, Bordeaux, Saint Pierre de Mons) BACKGROUND: The vineyard’s history of this property, whose tradition dates back to the 19th century, really began in 1985 when Roland Belloc analyzed the unsatisfying condition of all the vineyards in Le Rose Sarron. Just after purchasing the Chateau, located in the commune of Saint Pierre de Mons in AOC Graves, he took the tough decision to replant all the vineyards and to work with a quality driven mind set. For 20 years Roland Belloc, helped by Philippe Rochet, fought together, day in day out, to develop the Château La Rose Sarron reputation with huge investments focused on modern equipment (vats, barrel cellars, storage building) which have been carefully planned in order to keep at the highest level this property. At the same time the two men promoted an efficient internal organization. Philippe Rochet has been a winemaker since 1983 and took over the property from his father-in-law Roland Belloc in 2008. Today Philippe is quietly preparing to pass the torch, notably to his son Damien who studied engineer. After all La Rose Sarron is an artisanal family business. PRESENT DAYS: Château La Rose Sarron includes 31 hectares cultivated with red grapes, 5 of which are dedicated to the Damien cuvée (named after the son, obviously), and 11 hectares planted with white varieties including 3 for the Anaïs cuvée (named after the daughter!). Global property production averages around 100.000 – 110.000 bottles per year, while the rest of the fruit is sold to wine merchants. The diversity of its terroir is a key element here: gravel, clay and silt, on one side, allow the production of excellent red wines, while the siliceous soils offer charming and elegant white wines. -

Does Barrel Size Influence White Wine Aging Quality?

https://doi.org/10.20870/IVES-TR.2020.3305 Does barrel size influence white wine aging quality? >>> White wine is increasingly aged in oak barrels alcoholic strength (12.9±0.1 %vol.), titratable and volatile to enhance its stability, aromatic complexity and acidity (2.9±0.1 and 0.3±0.0 g/L, respectively) remained organoleptic properties. Thus, this research aimed constant beyond the malolactic fermentation. As observed in Figure 1, wine color was as well not impacted by barrel to highlight chemical and sensory differences in size. In addition, no signs of oxidation nor browning were Sauvignon Blanc wines linked to barrel size. Oenological observed during aging for any of the wines analyzed. parameters, color, total phenolics and fruity aroma In the case of Fruité toasting, no significant differences were were not generally impacted by barrel size. Meanwhile, found between both barrel sizes regarding total phenolic content of wines throughout the whole experimentation. the smaller the barrel, the higher the extraction of 0,35 Meanwhile, the Épicé 225 L barrel (231 ± 3 mg GA/L oak woody volatiles. From an organoleptic point of 0,30 wine) led to a slightly higher total phenolic contentÉpicé toasting than view, Sauvignon Blanc varietal aromas and typicity the largest barrel size (214 ± 0,251 mg GA/L wine) of the seemed to be better preserved by 500 L barrels. <<< same toasting: the ratio of surface0,20 area to wine volume is 2 greater in the smallest barrel (0.90,15 m / hL wine for 225 L 2 Abs at 420 nm barrel and 0.7 m /hL wine for 5000,10 L barrel). -

Wine by Glass 175Ml Champagne

Wine by glass 175ml Champagne Christophe Mignon Brut NV £13.00 Our excellent house champagne from a talented boutique producer 100% Pinot Meunier. Full bodied and rich. Champagne E.Prudhomme Rose NV £13.00 Extraordinary rose from the same producer as our Christophe Mignon. 100% Pinot Meunier. Guy Cadel Champagne Demi sec NV £10.5 0 Great Champagne with a bit of residual sweetness. Works well as an aperitif or with fruity desserts. Sparkling wines Prosecco Argeo Rugger , Treviso Italy NV £7.00 Fruity and refreshing, uncomplicated but well-made sparkling wine. Bluebell ‘Hindleap’ Rose, Sussex 2011 £10.50 A delightful local wine from a small vineyard. Traditional method & classic champagne grape varieties combined to create a delicate, fruity wine with salmon blush. An amazing aperitif. Rose wine Bordeaux Clairet, Chateau Vignol, France 2014 £7.0 0 A very interesting wine, deeply coloured rosé. Great aperitif but works well with food. White wines Château Martinon, Entre-deux-Mers. Bordeaux France 2014 £6.00 Sauvignon Blanc, Muscadelle and Sémillon. Dry. Our amazing house wine! Riesling ‘Urstuck’ Trocken Paulinshof, Mosel Germany 2014 £9.00 Off-dry, fresh and fruity with hints of orange peel and bergamot. Bacchus, Albourne Estate, Sussex England 2014 £9.00 Excellent dry wine from a vineyard just outside of Brighton! Light and floral with refreshing elderflower flavours. Sauvignon Blanc ‘La Barry’ Meinert, Elgin, South Africa 2014 £7.00 From the cooler, lesser known southern tip of South Africa this classic new world won’t disappoint Sauvignon Blanc lovers. Red wines Blaufrankish, Strehn Deutschkreuz, Burgenland Austria 2013 £6 .00 Deeply coloured, lighter style of wine with hints of cherries. -

Interesting White Wine Varietals

Interesting White Wine Varietals. Many of these maybe known as blending grape varietals, but one should really taste some of these. The Quiet Enoteca believes you may find a new favorite or two. Interesting Variety Also Called Country Style Varietal Notes Notable Growing Regions - Whites of origin Appellations/Country Albarino Cainho Branco Portugal - Dry This wine is typically medium to high acid and has Spain: Rias Baixas DO - Alvarinho Iberia floral and stone fruit notes. Peach and Apricot with Portugal: Vinho Verde DOC a bit of grassiness to them. Has a similar taste as a US: Los Carneros AVA - Voigner CA, Umpqua Valley AVA - OR. Aligote Burgundy, Dry Aligote is mostly used as a blending wine. As a France: Bourgogne Aligote France single varietal wine it may also be blended with up AOC. to 15% chardonnay. Aligote is meant to be drunk young has a high acidity and notes of apples and lemons with herbaceous overtones. Fiano Apianum, Campania Dry Fiano is a white wine that can age and as it does so Italy: Campania region - apiana, fiana - Italy it takes on spicy and nutty notes over time. When Fiano Di Avellino DOCG young honey and spice dominate. Fiano has long been a blending wine with a long list of complimentary varietals. With Many DOC/G allowing for a portion of Fiano in the mix. Furmint Tokaji - Dry or Very Sweet Furmint is probably the most notable grape of Hungary: Tokaj PDO Hungary Hungary. The dry version of Furmint is similar to an oaked Chardonnay from Sonoma or Oregon. Nice dry, with a nice mouth feel, at least the one we tried.