Non-Signatories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Serbia Ipard Programme for 2014-2020

EN ANNEX Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection Republic of Serbia REPUBLIC OF SERBIA IPARD PROGRAMME FOR 2014-2020 27th June 2019 1 List of Abbreviations AI - Artificial Insemination APSFR - Areas with Potential Significant Flood Risk APV - The Autonomous Province of Vojvodina ASRoS - Agricultural Strategy of the Republic of Serbia AWU - Annual work unit CAO - Competent Accrediting Officer CAP - Common Agricultural Policy CARDS - Community Assistance for Reconstruction, Development and Stabilisation CAS - Country Assistance Strategy CBC - Cross border cooperation CEFTA - Central European Free Trade Agreement CGAP - Code of Good Agricultural Practices CHP - Combined Heat and Power CSF - Classical swine fever CSP - Country Strategy Paper DAP - Directorate for Agrarian Payment DNRL - Directorate for National Reference Laboratories DREPR - Danube River Enterprise Pollution Reduction DTD - Dunav-Tisa-Dunav Channel EAR - European Agency for Reconstruction EC - European Commission EEC - European Economic Community EU - European Union EUROP grid - Method of carcass classification F&V - Fruits and Vegetables FADN - Farm Accountancy Data Network FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization FAVS - Area of forest available for wood supply FOWL - Forest and other wooded land FVO - Food Veterinary Office FWA - Framework Agreement FWC - Framework Contract GAEC - Good agriculture and environmental condition GAP - Gross Agricultural Production GDP - Gross Domestic Product GEF - Global Environment Facility GEF - Global Environment Facility GES -

1 Program and Plan for The

PROGRAM AND PLAN FOR THE SOLUTION OF THE CRISIS IN PRESEVO, BUJANOVAC AND MEDVEDJA MUNICIPALITIES Annex 5: Agreement on the solution of the crisis in Bujanovac, Presevo and Medvedja municipalities This Agreement is concluded between: The Governments of the Republic of Serbia and of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and The Albanian ethnic community in the municipalities of Presevo, Bujanovac and Medvedja. The implementation of this Agreement is supported and in the framework of the Joint Commission guaranteed by the international community, under the auspices of the United Nations. 1. The subject of this Agreement is the solution of the crisis in the municipalities of Presevo, Bujanovac, and Medvedja, in a peaceful way. 2. The Parties to the Agreement agree that the common objectives for the solution of the crisis are: a) The establishment of the respect of the constitutional-legal order, i.e. of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Serbia and of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia on that part of their territory, and the assurance of full normalization of work of the organs of the state, of the organs of local self-government and of other legal organs in that territory; b) The establishment of full personal security and security of property of all citizens and of full and undisturbed freedom of their movement in all parts of the territory of these municipalities, which shall be assured by the complete disbanding and disarmament of the extremists, by the restoration of security and peace in the region, and by making possible the return of all citizens - refugees to their households; c) The development of multiethnic and multiconfessional society based on democratic principles with the respect of all human, political and minority rights and liberties according to the highest standards; d) Prosperous and rapid economic and social development of the region with international financial assistance in the best interest of all citizens who live in the region. -

Victims Assistance Factsheet

FACTSHEETS How to implement victim assistance obligations? UNDER THE MINE BAN TREATY OR THE CONVENTION ON CLUSTER MUNITIONS Concrete actions to improve the quality of life of victims and persons with disabilities VICTIM ASSISTANCE FACTSHEETS INTRODUCTION Assistance to victims of mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) is an obligation for States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty (MBT) and the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM). The Cartagena Action Plan and the Vientiane Action Plan include specific commitments that States Parties have agreed on to implement their victim assistance (VA) obligations effectively, in particular to improve the quality of life of victims. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) provides the most comprehensive framework to address the needs & advances the rights of all persons with disabilities (PwD), including mine/ERW survivors. Regional frameworks on disability and development are also relevant, such as the Incheon Strategy to “Make the Right Real” for Persons with Disability in Asia and the Pacificand the African Decade of Persons with Disabilities. OBJECTIVE OF THESE FACTSHEETS The Victim Assistance Factsheets were developed by Handicap International (HI) as a tool to provide concise information on what victim assistance (VA) is and on how to translate it into concrete actions that have the potential to improve the quality of life of mine/ERW victims and persons with disabilities. The factsheets target States Parties affected by mine/ERW, States Parties in a position to provide assistance, as well as organizations of survivors and other PwD, and other civil society - and international organizations. METHODOLOGY The factsheets build on a review of existing literature on VA, Disability and Inclusive Development, including publications such as the WHO Community-Based Rehabilitation Guidelines, sector and country-specific publications by HI, as well as others by the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Implementation Support Unit, the ICRC and other organizations. -

Recent Evolution of Poverty

Report No. 19385-AM ImprovingSocial Assistancein Armenia Public Disclosure Authorized June8,1999 Human Development Unit Country Department III Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACBA Agriculture Credit Bank of Armenia ASIF Armenia Social Investment Fund BBP Basic Benefit Package CAS Country Assistance Strategy CIS Commonwealth of Independent States ECHO European Community Humanitarian Office FAR Fund for Armenian Relief FBS Family Budget Survey FSU Former Soviet Union GDP Gross Domestic Product GOA Government of Armenia HAC Humanitarian Assistance Commission HACC Humanitarian Aid Coordination Commission HBS Household Budget Survey HES Health and Education Survey IDA International Development Association IMF International Monetary Fund JMP Jinishian Memorial Program MA Mission Armenia NGO Non-governmental Organization(s) OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development PAYG Pay-As-You-Go SDS Armenian State Department of Statistics SSC Social Services Center UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund USAID United States Agency for International Development VAT Value Added Tax WFP World Food Program YICRD Yerevan Institute of Computer Research and Development YSU Yerevan State University Vice President Johannes Linn, ECAVP Country Director Judy O'Connor, ECCO3 Sector Manager Michal Rutkowski, ]ECSHD Task Team Leader Alexandre Marc, ECSHD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The preparation of the report was managed by Alexandre Marc (Sr. Human Resources Specialist). Margaret Grosh (Sr. Economist) was responsible for the research work on targeting which she carried out in collaboration with Elena Glinskaya (Consultant), and was the main author of the chapter on targeting of social assistance. -

Alternative Anti-Personnel Mines the Next Generations Landmine Action Consists of the Following Co-Operating Organisations

Alternative anti-personnel mines The next generations Landmine Action consists of the following co-operating organisations: ActionAid International Alert Refugee Council Action for Southern Africa Jaipur Limb Campaign Royal College of Paediatrics & Action on Disability and Development Jesuit Refugee Service Child Health Adopt-A-Minefield UK MEDACT Saferworld Afghanaid Medical & Scientific Aid for Vietnam Laos & Save the Children UK Amnesty International UK Cambodia Soroptimist International UK Programme Action Committee CAFOD Medical Educational Trust Tearfund Cambodia Trust Merlin United Nations Association Campaign Against Arms Trade Mines Advisory Group United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) UK Child Advocacy International Motivation VERTIC Christian Aid Mozambique Angola Committee War Child Comic Relief Omega Foundation War on Want Concern Worldwide One World Action Welsh Centre for International Affairs Disability Awareness in Action Oxfam GB Women’s International League for Peace & Environmental Investigation Agency Pax Christi Freedom Global Witness Peace Pledge Union World Vision UK Handicap International (UK) People and Planet Hope for Children POWER Human Rights Watch Quaker Peace & Service The member organisations of the German Initiative to Ban Landmines are: Bread for the World Social Service Agency of the Evangelical Church Misereor Christoffel Mission for the Blind in Germany Oxfam Germany German Justitia et Pax Commission Eirene International Pax Christi German Committee for Freedom from Hunger Handicap International Germany -

The State of Law

The State of Law The State of Law Comparative Perspectives on the Rule of Law in Germany and Vietnam Ulrich von Alemann/Detlef Briesen/ Lai Quoc Khanh (eds.) Gefördert und gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Gerda Henkel Stiftung, der Anton- Betz-Stiftung der Rheinischen Post und der Gesellschaft von Freunden und Förderern der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf e.V. (GFFU). Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2017 http://www.dupress.de Satz und Layout: Duc-Viet Publikationen Umschlaggestaltung: Marvin P. Klähn Lektorat, Redaktion: Detlef Briesen Druck: KN Digital Printforce GmbH, Ferdinand-Jühlke-Straße 7, 99095 Erfurt. Der Fließtext ist gesetzt in Garamond 3 FV ISBN: 978-3-95758-053-5 Table of Contents Ulrich von Alemann/Detlef Briesen/Lai Quoc Khanh Introduction ......................................................................................... 9 I. Traditions Nguyen Thi Hoi A Brief History of the Idea of the State of Law and Its Basic Indicators ............................................................................. 17 Pham Duc Anh Thoughts and Policies on Governing the People under the Ly-Tran and the Early Le -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL an Evaluation of the Performance Of

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL An Evaluation of the Performance of Multi-static Handheld Ground Penetrating Radar using Full Wave Inversion for Landmine Detection Being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Suki Dauda Sule, MSc, B.Eng. (Hons) June 2018 Acknowledgments I would like to begin by thanking my first supervisor, Dr. Kevin Paulson for his support and guidance before and throughout my research. His enthusiasm, optimism and availability have been critical to the completion of this work despite the challenges. To my second supervisor Mr. Nick Riley whose persistent constructive criticism and suggestions always helped to point me in the right direction. My special gratitude goes to my sponsor, the Petroleum Technology Development Fund (PTDF) of Nigeria for providing me with an exceptional full scholarship, one of the best in the world, without which this research would not have been possible. I’m also grateful to the humanitarian demining research teams at the University of Manchester led by Professors Anthony Peyton and William Lionheart for their support. I thank the Computer Simulation Technology (CST) GmbH technical support for the CST STUDIO SUITE. I will not forget the administrative support of Jo Arnett and Glen Jack in processing my numerous requests, expense claims and other academic requisitions. To my colleagues, my laboratory mate and other PhD students in the Electronic Engineering Department for their moral support and encouragement. I’m very thankful to Pastor Isaac Aleshinloye and the Amazing Grace Chapel, Hull family for providing me with a place of spiritual support, friendship, opportunity for community service and a place to spend my time outside of academic study productively. -

<I>Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Bibliography

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Digitized Books 2000 Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Bibliography - Volume II: English and European Languages Shaista Wahab Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wahab, Shaista, "Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Bibliography - Volume II: English and European Languages " (2000). Books in English. Paper 41. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno/41 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. v0ILuNJI: 11: ISH AND EUROPEAN LANGUAGE SHATSTA WAHAB Dagefimle Publishing Lincoln, Nebraska Copl;rii$i~ G3009 Univcrsit!; oSNebraska at Omaha. All rights rcscrved. No part of this publication may be reproducc.d. stored in n rm-ieval syslcm, or Iransmitted in any fonn or by any nwans, electronic, niccllanical, photocopied, recorded. or O~~IL'ITV~SC, without 111c prior uritten permission of the au~lior.For in t'ornlation. wi[c Arthur Paul Afgllanistan (:ollcction, University Library. Univer-sih of Ncbrnska at Omaha. Onlaha. NE GS 182-0237 Library of Coligrcss C:ii;~logi~~g-in-Puhlic:i~ionData \\rnImb, Shnisla. Arrllur Paul :\l'ghauis~nnCollcc~ion hbliograpliy i Sllais~n\Vahab. v. : ill. ; 23 cln. -

Agriculture and Food Processing in Armenia

SAMVEL AVETISYAN AGRICULTURE AND FOOD PROCESSING IN ARMENIA YEREVAN 2010 Dedicated to the memory of the author’s son, Sergey Avetisyan Approved for publication by the Scientifi c and Technical Council of the RA Ministry of Agriculture Peer Reviewers: Doctor of Economics, Prof. Ashot Bayadyan Candidate Doctor of Economics, Docent Sergey Meloyan Technical Editor: Doctor of Economics Hrachya Tspnetsyan Samvel S. Avetisyan Agriculture and Food Processing in Armenia – Limush Publishing House, Yerevan 2010 - 138 pages Photos courtesy CARD, Zaven Khachikyan, Hambardzum Hovhannisyan This book presents the current state and development opportunities of the Armenian agriculture. Special importance has been attached to the potential of agriculture, the agricultural reform process, accomplishments and problems. The author brings up particular facts in combination with historic data. Brief information is offered on leading agricultural and processing enterprises. The book can be a useful source for people interested in the agrarian sector of Armenia, specialists, and students. Publication of this book is made possible by the generous fi nancial support of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and assistance of the “Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development” Foundation. The contents do not necessarily represent the views of USDA, the U.S. Government or “Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development” Foundation. INTRODUCTION Food and Agriculture sector is one of the most important industries in Armenia’s economy. The role of the agrarian sector has been critical from the perspectives of the country’s economic development, food safety, and overcoming rural poverty. It is remarkable that still prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia made unprecedented steps towards agrarian reforms. -

The Network Politics of International Statebuilding: Intervention and Statehood in Post-2001 Afghanistan

The Network Politics of International Statebuilding: Intervention and Statehood in Post-2001 Afghanistan Submitted by Timor Sharan to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics In October 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on international intervention and statebuilding in post- 2001 Afghanistan. It offers an alternative lens, a network lens, to understand the complexity of internationally sponsored state re-building and transformation. It therefore analyses how political power is assembled and flows through political networks in statebuilding, with an eye to the hitherto ignored endogenous political networks. The empirical chapters investigate the role and power dynamics of Afghan political network in re-assembling and transforming the post-2001 state once a political settlement is reached; how everyday political network practices shape the nature of statehood and governance; and subsequently how these power dynamics and practices contribute towards political order/violence and stability/instability. This thesis challenges the dominant wisdom that peacebuilding is a process of democratisation or institutionalisation, showing how intervention has unintentionally produced the democratic façade of a state, underpinning by informal power structures of Afghan politics. The post-2001 intervention has fashioned a ‘network state’ where the state and political networks have become indistinguishable from one another: the empowered network masquerade as the state. -

Glaciers Dynamics Over the Last One Century in the Kodori River Basin, Caucasus Mountains, Georgia, Abkhazeti

American Journal of Environmental Protection 2015; 4(3-1): 22-28 Published online June 23, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajep) doi: 10.11648/j.ajep.s.2015040301.14 ISSN: 2328-5680 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5699 (Online) Glaciers Dynamics Over the Last One Century in the Kodori River Basin, Caucasus Mountains, Georgia, Abkhazeti Levan G. Tielidze 1, Lela Gadrani 1, Mariam Tsitsagi 1, Nino Chikhradze 1,2 1Vakhushti Bagrationi Institute of Geography, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia 2Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia Email address: [email protected] (L. G. Tielidze), [email protected] (L. G. Tielidze) To cite this article: Levan G. Tielidze, Lela Gadrani, Mariam Tsitsagi, Nino Chikhradze. Glaciers Dynamics Over the last One Century in the Kodori River Basin, Caucasus Mountains, Georgia, Abkhazeti. American Journal of Environmental Protection . Special Issue: Applied Ecology: Problems, Innovations. Vol. 4, No. 3-1, 2015, pp. 22-28. doi: 10.11648/j.ajep.s.2015040301.14 Abstract: This paper considers the last one century’s dynamics of the glaciers in the Kodori River basin, which is located on the southern slope of the Greater Caucasus in Georgia. The latest statistical information is also given about the glaciers located in the individual river basins; Their morphological types, exposition and the dynamics are considered according to the individual years. In our research, we used the Catalogue of the glaciers of Georgia compiled by K. Podozerskiy in 1911. We also used the military topographic maps with the scale of 1:25 000 and 1:50 000 drawn up in 1960, where there are mapped in detail the glaciers and the ends of their ice tongues on the southern slope of Greater Caucasus of those times. -

States' Commitment to Conventional Weapons Destruction F United

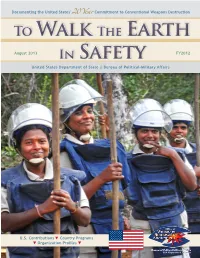

Documenting the United States’ Commitment to Conventional Weapons Destruction 20Year To Walk The Earth August 2013 In Safety FY2012 United States Department of State | Bureau of Political-Military Affairs U.S. Contributions Country Programs Organization Profiles 180 165 150 135 120 105 90 75 60 45 30 15 0 15 30 45 60 75 90 105 120 135 150 165 180 ON THE COVERS Table of Contents General Information 20 Years of U.S. Commitment to CWD ��������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Conventional Weapons Destruction Overview ����������������������������������������������������������������6 FY2012 Grantees �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 58 List of Common Acronyms . 60 FY2012 Funding Chart �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 61 U.S. Government Interagency Partners 75 Female deminers prepare for work in Sri Lanka. CDC �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 53 Sri Lanka is contaminated by landmines and ex- MANPADS Task Force . 56 plosive remnants of war from over three decades PM/WRA . 13 of armed conflict. From FY2002–FY2012 the U.S. has invested more than $35 million in convention- USAID ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 45 al weapons destruction programs in Sri Lanka. Photo courtesy of Sean Sutton/MAG. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE DTRA .