Surgical Management of Adrenocortical Carcinoma an Evidence-Based Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HER2 Inhibition in Gastro-Oesophageal Cancer: a Review Drawing on Lessons Learned from Breast Cancer

Submit a Manuscript: http://www.f6publishing.com World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018 July 15; 10(7): 159-171 DOI: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i7.159 ISSN 1948-5204 (online) REVIEW HER2 inhibition in gastro-oesophageal cancer: A review drawing on lessons learned from breast cancer Hazel Lote, Nicola Valeri, Ian Chau Hazel Lote, Nicola Valeri, Centre for Molecular Pathology, Accepted: May 30, 2018 Institute of Cancer Research, Sutton SM2 5NG, United Kingdom Article in press: May 30, 2018 Published online: July 15, 2018 Hazel Lote, Nicola Valeri, Ian Chau, Department of Medicine, Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton SM2 5PT, United Kingdom ORCID number: Hazel Lote (0000-0003-1172-0372); Nicola Valeri (0000-0002-5426-5683); Ian Chau (0000-0003-0286-8703). Abstract Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)- Author contributions: Lote H wrote the original manuscript and revised it following peer review comments; Valeri N reviewed inhibition is an important therapeutic strategy in HER2- the manuscript; Chau I reviewed and contributed to the content of amplified gastro-oesophageal cancer (GOC). A significant the manuscript. proportion of GOC patients display HER2 amplification, yet HER2 inhibition in these patients has not displayed Supported by National Health Service funding to the National the success seen in HER2 amplified breast cancer. Mu- Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at ch of the current evidence surrounding HER2 has been the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of obtained from studies in breast cancer, and we are only re- Cancer Research, No. A62, No. A100, No. A101 and No. A159; Cancer Research UK funding, No. -

Adrenal Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Adrenal

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Adrenal Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Learn more about the risk factors for adrenal cancer. ● Adrenal Cancer Risk Factors ● What Causes Adrenal Cancer? Prevention Since there are no known preventable risk factors for this cancer, it is not possible to prevent this disease. Adrenal Cancer Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that changes your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed. Scientists have found few risk factors that make a person more likely to develop adrenal cancer. Even if a patient does have one or more risk factors for adrenal cancer, it is impossible to know for sure how much that risk factor contributed to causing the cancer. 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. Many people with risk factors never develop adrenal cancer, while others with this disease may have few or no known risk factors. Genetic syndromes The majority of adrenal cortex cancers are not inherited (sporadic), but some (up to 15%) are caused by a genetic defect. This is more common in adrenal cancers in children. Li-Fraumeni syndrome The Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a rare condition that is most often caused by a defect in the TP53 gene. -

Endocrine Pathology (537-577)

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION THE BASIC AND TRANSLATIONAL PATHOLOGY RESEARCH JOURNAL LI VOLUME 99 | SUPPLEMENT 1 | MARCH 2019 2019 ABSTRACTS ENDOCRINE PATHOLOGY (537-577) MARCH 16-21, 2019 PLATF OR M & 2 01 9 ABSTRACTS P OSTER PRESENTATI ONS EDUCATI ON C O M MITTEE Jason L. Hornick , C h air Ja mes R. Cook R h o n d a K. Y a nti s s, Chair, Abstract Revie w Board S ar a h M. Dr y and Assign ment Co m mittee Willi a m C. F a q ui n Laura W. La mps , Chair, C ME Subco m mittee C ar ol F. F ar v er St e v e n D. Billi n g s , Interactive Microscopy Subco m mittee Y uri F e d ori w Shree G. Shar ma , Infor matics Subco m mittee Meera R. Ha meed R aj a R. S e et h al a , Short Course Coordinator Mi c h ell e S. Hir s c h Il a n W ei nr e b , Subco m mittee for Unique Live Course Offerings Laksh mi Priya Kunju D a vi d B. K a mi n s k y ( Ex- Of ici o) A n n a M ari e M ulli g a n Aleodor ( Doru) Andea Ri s h P ai Zubair Baloch Vi nita Parkas h Olca Bast urk A nil P ar w a ni Gregory R. Bean , Pat h ol o gist-i n- Trai ni n g D e e p a P atil D a ni el J. -

Endocrine Surgery Goals and Objectives

Lenox Hill Hospital Department of Surgery Endocrine Surgery Goals and Objectives Medical Knowledge and Patient Care: Residents must demonstrate knowledge and application of the pathophysiology and epidemiology of the diseases listed below for this rotation, with the pertinent clinical and laboratory findings, differential diagnosis and therapeutic options including preventive measures, and procedural knowledge. They must show that they are able to gather accurate and relevant information using medical interviewing, physical examination, appropriate diagnostic workup, and use of information technology. They must be able to synthesize and apply information in the clinical setting to make informed recommendations about preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic options, based on clinical judgement, scientific evidence, and patient preferences. They should be able to prescribe, perform, and interpret surgical procedures listed below for this rotation. All Residents are expected to understand: 1. Normal physiology and anatomy of the thyroid glands. 2. Normal physiology and anatomy of the parathyroid glands. 3. Normal physiology and anatomy of the adrenal glands 4. Normal physiology of the pancreatic neuroendocrine cells. 5. Normal physiology of the pituitary gland. Disease-Based Learning Objectives: Hyperfunctioning Thyroid and Hypothyroid State: 1. Physiology of Grave’s disease and toxic goiter. 2. Management of a patient in hyperthyroid storm. 3. Medical and surgical treatment options for hyperthyroidism. 4. Physiology of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and hypothyroidism. Thyroid Neoplasm: 1. Workup of a cold thyroid nodule. 2. Surgical management of papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. 3. Adjuvant therapy for thyroid neoplasms. 4. Postoperative medical management and long-term follow-up of thyroid cancer. Hyperparathyroidism: 1. Diagnosis and work-up of hypercalcemia and primary, secondary, and tertiary hyperparathyroidism. -

Therapeutic Targeting of the IGF Axis

cells Review Therapeutic Targeting of the IGF Axis Eliot Osher and Valentine M. Macaulay * Department of Oncology, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 7DQ, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1865617337 Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 9 August 2019; Published: 14 August 2019 Abstract: The insulin like growth factor (IGF) axis plays a fundamental role in normal growth and development, and when deregulated makes an important contribution to disease. Here, we review the functions mediated by ligand-induced IGF axis activation, and discuss the evidence for the involvement of IGF signaling in the pathogenesis of cancer, endocrine disorders including acromegaly, diabetes and thyroid eye disease, skin diseases such as acne and psoriasis, and the frailty that accompanies aging. We discuss the use of IGF axis inhibitors, focusing on the different approaches that have been taken to develop effective and tolerable ways to block this important signaling pathway. We outline the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, and discuss progress in evaluating these agents, including factors that contributed to the failure of many of these novel therapeutics in early phase cancer trials. Finally, we summarize grounds for cautious optimism for ongoing and future studies of IGF blockade in cancer and non-malignant disorders including thyroid eye disease and aging. Keywords: IGF; type 1 IGF receptor; IGF-1R; cancer; acromegaly; ophthalmopathy; IGF inhibitor 1. Introduction Insulin like growth factors (IGFs) are small (~7.5 kDa) ligands that play a critical role in many biological processes including proliferation and protection from apoptosis and normal somatic growth and development [1]. IGFs are members of a ligand family that includes insulin, a dipeptide comprised of A and B chains linked via two disulfide bonds, with a third disulfide linkage within the A chain. -

Primary and Acquired Resistance to Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer: Unveiling the Mechanisms Underlying of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy

cancers Review Primary and Acquired Resistance to Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer: Unveiling the Mechanisms Underlying of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy Laura Boyero 1 , Amparo Sánchez-Gastaldo 2, Miriam Alonso 2, 1 1,2,3, , 1,2, , José Francisco Noguera-Uclés , Sonia Molina-Pinelo * y and Reyes Bernabé-Caro * y 1 Institute of Biomedicine of Seville (IBiS) (HUVR, CSIC, Universidad de Sevilla), 41013 Seville, Spain; [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (J.F.N.-U.) 2 Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio, 41013 Seville, Spain; [email protected] (A.S.-G.); [email protected] (M.A.) 3 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Cáncer (CIBERONC), 28029 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.M.-P.); [email protected] (R.B.-C.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 16 November 2020; Accepted: 9 December 2020; Published: 11 December 2020 Simple Summary: Immuno-oncology has redefined the treatment of lung cancer, with the ultimate goal being the reactivation of the anti-tumor immune response. This has led to the development of several therapeutic strategies focused in this direction. However, a high percentage of lung cancer patients do not respond to these therapies or their responses are transient. Here, we summarized the impact of immunotherapy on lung cancer patients in the latest clinical trials conducted on this disease. As well as the mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance to immunotherapy in this disease. Abstract: After several decades without maintained responses or long-term survival of patients with lung cancer, novel therapies have emerged as a hopeful milestone in this research field. -

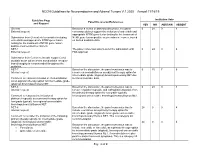

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19 Guideline Page Institution Vote Panel Discussion/References and Request YES NO ABSTAIN ABSENT General Based on a review of data and discussion, the panel 0 24 0 4 External request: consensus did not support the inclusion of entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion testing for the treatment of Submission from Genentech to consider including NTRK gene fusion-positive neuroendocrine cancer, based entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion on limited available data. testing for the treatment of NTRK gene fusion- positive neuroendocrine cancers. NET-1 The panel consensus was to defer the submission until 0 24 0 4 External request: FDA approval. Submission from Curium to include copper Cu 64 dotatate as an option where somatostatin receptor- based imaging is recommended throughout the guideline. NET-7 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 15 7 6 Internal request: remove chemoradiation as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET due Comment to reassess inclusion of chemoradiation to limited available data. as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 24 0 4 Internal request: remove cisplatin/etoposide and carboplatin/etoposide from the primary therapy option for low grade (typical), Comment to reassess the inclusion of locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. platinum/etoposide as a primary therapy option for low grade (typical), locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 24 0 0 4 Internal request: include everolimus as a primary therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical), locoregional unresectable Comment to consider the inclusion of the following bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. -

Insulin-Like Growth Factor Pathway and the Thyroid

REVIEW published: 04 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.653627 Insulin-Like Growth Factor Pathway and the Thyroid Terry J. Smith* Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Kellogg Eye Center, Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology, and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, United States The insulin-like growth factor (IGF) pathway comprises two activating ligands (IGF-I and IGF-II), two cell-surface receptors (IGF-IR and IGF-IIR), six IGF binding proteins (IGFBP) and nine IGFBP related proteins. IGF-I and the IGF-IR share substantial structural and functional similarities to those of insulin and its receptor. IGF-I plays important regulatory roles in the development, growth, and function of many human tissues. Its pathway intersects with those mediating the actions of many cytokines, growth factors and hormones. Among these, IGFs impact the thyroid and the hormones that it generates. Further, thyroid hormones and thyrotropin (TSH) can influence the biological effects of growth hormone and IGF-I on target tissues. The consequences of this two-way interplay can be far-reaching on many metabolic and immunologic processes. Specifically, IGF-I supports normal function, volume and hormone synthesis of the thyroid gland. Some of these effects are mediated through enhancement of sensitivity to the actions of TSH while Edited by: others may be independent of pituitary function. IGF-I also participates in pathological Jeff M. P. Holly, conditions of the thyroid, including benign enlargement and tumorigenesis, such as those University of Bristol, United Kingdom ’ Reviewed by: occurring in acromegaly. With regard to Graves disease (GD) and the periocular process Leonard Girnita, frequently associated with it, namely thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO), IGF-IR Karolinska Institutet (KI), Sweden has been found overexpressed in orbital connective tissues, T and B cells in GD and TAO. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0172932 A1 Peyman (43) Pub

US 20170172932A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0172932 A1 Peyman (43) Pub. Date: Jun. 22, 2017 (54) EARLY CANCER DETECTION AND A 6LX 39/395 (2006.01) ENHANCED IMMUNOTHERAPY A61R 4I/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (71) Applicant: Gholam A. Peyman, Sun City, AZ CPC .......... A61K 9/50 (2013.01); A61K 39/39558 (US) (2013.01); A61K 4I/0052 (2013.01); A61 K 48/00 (2013.01); A61K 35/17 (2013.01); A61 K (72) Inventor: sham A. Peyman, Sun City, AZ 35/15 (2013.01); A61K 2035/124 (2013.01) (21) Appl. No.: 15/143,981 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: May 2, 2016 A method of therapy for a tumor or other pathology by administering a combination of thermotherapy and immu Related U.S. Application Data notherapy optionally combined with gene delivery. The combination therapy beneficially treats the tumor and pre (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 14/976,321, vents tumor recurrence, either locally or at a different site, by filed on Dec. 21, 2015. boosting the patient’s immune response both at the time or original therapy and/or for later therapy. With respect to Publication Classification gene delivery, the inventive method may be used in cancer (51) Int. Cl. therapy, but is not limited to such use; it will be appreciated A 6LX 9/50 (2006.01) that the inventive method may be used for gene delivery in A6 IK 35/5 (2006.01) general. The controlled and precise application of thermal A6 IK 4.8/00 (2006.01) energy enhances gene transfer to any cell, whether the cell A 6LX 35/7 (2006.01) is a neoplastic cell, a pre-neoplastic cell, or a normal cell. -

Neoplastic Metastases to the Endocrine Glands

27 1 Endocrine-Related A Angelousi et al. Metastases to endocrine 27:1 R1–R20 Cancer organs REVIEW Neoplastic metastases to the endocrine glands Anna Angelousi1, Krystallenia I Alexandraki2, George Kyriakopoulos3, Marina Tsoli2, Dimitrios Thomas2, Gregory Kaltsas2 and Ashley Grossman4,5,6 1Endocrine Unit, 1st Department of Internal Medicine, Laiko Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece 2Endocrine Unit, 1st Department of Propaedeutic Medicine, Laiko University Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece 3Department of Pathology, General Hospital ‘Evangelismos’, Αthens, Greece 4Department of Endocrinology, OCDEM, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 5Neuroendocrine Tumour Unit, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK 6Centre for Endocrinology, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK Correspondence should be addressed to A Angelousi: [email protected] Abstract Endocrine organs are metastatic targets for several primary cancers, either through Key Words direct extension from nearby tumour cells or dissemination via the venous, arterial and f glands lymphatic routes. Although any endocrine tissue can be affected, most clinically relevant f cancer metastases involve the pituitary and adrenal glands with the commonest manifestations f metastases being diabetes insipidus and adrenal insufficiency respectively. The most common f pituitary primary tumours metastasing to the adrenals include melanomas, breast and lung f adrenal carcinomas, which may lead to adrenal insufficiency in the presence of bilateral adrenal f thyroid involvement. Breast and lung cancers are the most common primaries metastasing to f ovaries the pituitary, leading to pituitary dysfunction in approximately 30% of cases. The thyroid gland can be affected by renal, colorectal, lung and breast carcinomas, and melanomas, but has rarely been associated with thyroid dysfunction. -

Surgical Indications and Techniques for Adrenalectomy Review

THE MEDICAL BULLETIN OF SISLI ETFAL HOSPITAL DOI: 10.14744/SEMB.2019.05578 Med Bull Sisli Etfal Hosp 2020;54(1):8–22 Review Surgical Indications and Techniques for Adrenalectomy Mehmet Uludağ,1 Nurcihan Aygün,1 Adnan İşgör2 1Department of General Surgery, Sisli Hamidiye Etfal Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey 2Department of General Surgery, Bahcesehir University Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract Indications for adrenalectomy are malignancy suspicion or malignant tumors, non-functional tumors with the risk of malignancy and functional adrenal tumors. Regardless of the size of functional tumors, they have surgical indications. The hormone-secreting adrenal tumors in which adrenalectomy is indicated are as follows: Cushing’s syndrome, arises from hypersecretion of glucocorticoids produced in fasciculata adrenal cortex, Conn’s syndrome, arises from an hypersecretion of aldosterone produced by glomerulosa adrenal cortex, and Pheochromocytomas that arise from adrenal medulla and produce catecholamines. Sometimes, bilateral adre- nalectomy may be required in Cushing's disease due to pituitary or ectopic ACTH secretion. Adenomas arise from the reticularis layer of the adrenal cortex, which rarely releases too much adrenal androgen and estrogen, may also develop and have an indication for adrenalectomy. Adrenal surgery can be performed by laparoscopic or open technique. Today, laparoscopic adrenalectomy is the gold standard treatment in selected patients. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy can be performed transperitoneally or retroperitoneoscopi- cally. Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. In the selection of the surgery type, the experience and habits of the surgeon are also important, along with the patient’s characteristics. The most common type of surgery performed in the world is laparoscopic transabdominal lateral adrenalectomy, which most surgeons are more familiar with. -

Development and Preclinical Evaluation of Cixutumumab Drug

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Development and preclinical evaluation of cixutumumab drug conjugates in a model of insulin growth factor receptor I (IGF‑1R) positive cancer Viswas Raja Solomon1, Elahe Alizadeh1, Wendy Bernhard2, Amal Makhlouf1,3, Siddesh V. Hartimath1, Wayne Hill2, Ayman El‑Sayed2, Kris Barreto2, Clarence Ronald Geyer 2 & Humphrey Fonge1,4* Overexpression of insulin growth factor receptor type 1 (IGF‑1R) is observed in many cancers. Antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) with PEGylated maytansine (PEG6‑DM1) show promise in vitro. We developed PEG6‑DM1 ADCs with low and high drug to antibody ratios (DAR) using an anti‑ IGF‑1R antibody cixutumumab (IMC‑A12). Conjugates with low (cixutumumab‑PEG6‑DM1‑Low) and high (cixutumumab‑PEG6‑DM1‑High) DAR as 3.4 and 7.2, respectively, were generated. QC was performed by UV spectrophotometry, HPLC, bioanalyzer, and biolayer‑interferometry. We compared the in vitro binding and internalization rates of the ADCs in IGF‑1R‑positive MCF‑7/Her18 cells. We radiolabeled the ADCs with 111In and used microSPECT/CT imaging and ex vivo biodistribution to understand their in vivo behavior in MCF‑7/Her18 xenograft mice. The therapeutic potential of the ADC was studied in vitro and in mouse xenograft. Internalization rates of all ADCs was high and increased over 48 h and EC50 was in the low nanomolar range. MicroSPECT/CT imaging and ex vivo 111 biodistribution showed signifcantly lower tumor uptake of In‑cixutumumab‑PEG6‑DM1‑High 111 111 compared to In‑cixutumumab‑PEG6‑DM1‑Low and In‑cixutumumab. Cixutumumab‑PEG6‑DM1‑ Low signifcantly prolonged the survival of mice bearing MCF‑7/Her18 xenograft compared with cixutumumab, cixutumumab‑PEG6‑DM1‑High, or the PBS control group.