098-Jorge-Federico-Osorio-Debussy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Pas Sur La Neige

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Mystères limpides: Time and Transformation in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige Debussy est mystérieux, mais il est clair. —Vladimir Jankélévitch STEVEN RINGS Introduction: Secrets and Mysteries sive religious orders). Mysteries, by contrast, are fundamentally unknowable: they are mys- Vladimir Jankélévitch begins his 1949 mono- teries for all, and for all time. Death is the graph Debussy et le mystère by drawing a dis- ultimate mystery, its essence inaccessible to tinction between the secret and the mystery. the living. Jankélévitch proposes other myster- Secrets, per Jankélévitch, are knowable, but ies as well, some of them idiosyncratic: the they are known only to some. For those not “in mysteries of destiny, anguish, pleasure, God, on the secret,” the barrier to knowledge can love, space, innocence, and—in various forms— take many forms: a secret might be enclosed in time. (The latter will be of particular interest a riddle or a puzzle; it might be hidden by acts in this article.) Unlike the exclusionary secret, of dissembling; or it may be accessible only to the mystery, shared and experienced by all of privileged initiates (Jankélévitch cites exclu- humanity, is an agent of “sympathie fraternelle et . commune humilité.”1 An abbreviated version of this article was presented as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music collo- 1Vladimir Jankélévitch, Debussy et le mystère (Neuchâtel: quium series in November 2007. I am grateful for the Baconnière, 1949), pp. 9–12 (quote, p. 10). See also his later comments I received on that occasion from students and revision and expansion of the book, Debussy et le mystère faculty. -

Download Booklet

552127-28bk VBO Debussy 10/2/06 8:40 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Nocturnes II. Fêtes . .. 6:56 2 String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 10 I. Animé et très décidé . 6:11 3 Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune . 10:29 4 Estampes III. Jardins sous la pluie . 3:43 5 Cello Sonata in D minor I. Prologue . 4:25 6 Suite bergamasque III. Clair de lune . 4:26 7 Violin Sonata in G minor II. Intermède: fantastique et léger . 4:17 8 24 Préludes No. 8. La fille aux cheveux de lin . 2:14 9 La Mer II. Jeux de vagues . 7:29 0 Pelléas et Melisande Act III Scene 1 . 14:22 ! 24 Préludes No. 12. Minstrels . 2:05 @ Rapsodie arabe for Alto Saxophone and Orchestra . 10:50 Total Timing . 78:00 CD2 1 Images II. Iberia . 21:43 2 24 Préludes No. 10. La cathédrale engloutie . 5:47 3 Marche écossaise sur un thème populaire . 6:10 4 Images I I. Reflets dans l’eau . 5:15 5 Rêverie . 3:50 6 L’isle joyeuse . 5:29 7 La Mer I. De l’aube à midi sur la mer . 9:18 8 La plus que lente . 4:44 9 Danse sacrée et danse profane II. Danse profane . 5:16 0 Two Arabesques Arabesque No. 1 . 5:05 ! Children’s Corner VI. Golliwogg’s Cake-walk . 3:09 Total Timing . 76:17 FOR FULL LIST OF DEBUSSY RECORDINGS WITH ARTIST DETAILS AND FOR A GLOSSARY OF MUSICAL TERMS PLEASE GO TO WWW.NAXOS.COM 552127-28bk VBO Debussy 10/2/06 8:40 PM Page 2 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) Children’s Corner VI. -

Debussy Préludes

Debussy Préludes Books I & II RALPH VOTAPEK ~ Debussy 24 Préludes Préludes, Book I (1909-1910) 37:13 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes (Lent et grave) 2:59 2 II. Voiles (Modéré) 3:09 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine (Animé) 2:07 4 IV. Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir (Modéré) 3:10 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri (Très modéré) 2:57 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige (Triste it lent) 3:47 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest (Animé et tumultueux) 3:23 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin (Très calme et doucement expressif) 2:29 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue (Modérément animé) 2:28 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie (Profondément calme) 5:54 11 XI. La danse de Puck (Capricieux et léger) 2:40 12 XII. Minstrels (Modéré) 2:10 Préludes, Book II (1912-1913) 36:04 13 I. Brouillards (Modéré) 2:38 14 II. Feuilles mortes (Lent et mélancolique) 2:55 15 III. La Puerta del Vino (Mouvement de Habanera) 3:19 16 IV. Les Fées sont d’exquises danseuses (Rapide et léger) 2:56 17 V. Bruyères (Calme) 2:42 18 VI. Général Lavine — eccentric (Dans le style et le mouvement d’un Cakewalk) 2:28 19 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune (Lent) 3:59 20 VIII. Ondine (Scherzando) 3:08 21 IX. Hommage à Samuel Pickwick, Esq., P.P.M.P.C. (Grave) 2:25 22 X. Canope (Très calme et doucement triste) 2:53 23 XI. -

Liner Notes (PDF)

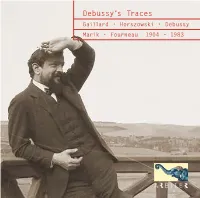

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

Item # Artist/Ensemble Album Title Quantity

Here at the Mary Pappert School of Music, our prestigious faculty are not only exemplary teachers, but are also active performers. Below are recordings available for purchase by many of these faculty members. Please print this form, indicate which CDs you would like to purchase, and mail along with a check (payable to Duquesne University) to: ATTN: Kathy Ingold Unless otherwise marked: Mary Pappert School of Music Duquesne University Single discs are $15. 00. 600 Forbes Avenue Double disc sets are $25.00. Pittsburgh, PA 15282 Shipping is $2.00 per CD up to $6.00. Please indicate each CD being ordered on a separate line. Item numbers are listed with each CD on the following pages. Item # Artist/Ensemble Album Title Quantity Total Number of single CDs ____________ X $15.00 = _______________ Total Number of double CDs ____________ X $25.00 = _______________ Total Number of individually priced CDs____________ X $____________ = _______________ Shipping ($2.00 per CD, maximum $6.00) =_______________ Mailing Address Grand Total =$_______________ Name:_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address:_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City:___________________________________________________________________State:________________Zip:______________________ For additional information -

ABSTRACT Final

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE BREADTH OF CHOPIN’S INFLUENCE ON FRENCH AND RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC OF THE LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURIES Jasmin Lee, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen School of Music Frederic Chopin’s legacy as a pianist and composer served as inspiration for generations of later composers of piano music, especially in France and Russia. Singing melodies, arpeggiated basses, sensitivity to sonorities, the use of rubato, pedal points, and the full range of the keyboard, plus the frequent use of character pieces as compositional forms characterize Chopin’s compositional style. Future composers Claude Debussy, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Nikolai Medtner, Gabriel Faure, and Maurice Ravel each paid homage to Chopin and his legacy by incorporating and enhancing aspects of his writing style into their own respective works. Despite the disparate compositional trajectories of each of these composers, Chopin’s influence on the development of their individual styles is clearly present. Such influence served as one of the bases for Romantic virtuoso works that came to predominate the late 19th and early 20th century piano literature. This dissertation was completed by performing selected works of Claude Debussy, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Gabriel Faure, Nikolai Medtner, and Maurice Ravel, in three recitals at the Gildenhorn Recital Hall in the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center of the University of Maryland. Compact Disc recordings of the recital are housed -

Orientalism As Represented in the Selected Piano Works by Claude Debussy

Chapter 4 ORIENTALISM AS REPRESENTED IN THE SELECTED PIANO WORKS BY CLAUDE DEBUSSY A prominent English scholar of French music, Roy Howat, claimed that, out of the many composers who were attracted by the Orient as subject matter, “Debussy is the one who made much of it his own language, even identity.”55 Debussy and Hahn, despite being in the same social circle, never pursued an amicable relationship.56 Even while keeping their distance, both composers were somewhat aware of the other’s career. Hahn, in a public statement from 1890, praised highly Debussy’s musical artistry in L'Apres- midi d'un faune.57 Debussy’s Exposure to Oriental Cultures Debussy’s first exposure to oriental art and philosophy began at Mallarmé’s Symbolist gatherings he frequented in 1887 upon his return to Paris from Rome.58 At the Universal Exposition of 1889, he had his first experience in the theater of Annam (Vietnam) and the Javanese Gamelan orchestra (Indonesia), which is said to be a catalyst 55Roy Howat, The Art of French Piano Music: Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, Chabrier (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 110 56Gavoty, 142. 57Ibid., 146. 58François Lesure and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/07353 (accessed April 4, 2011). 33 34 in his artistic direction. 59 In 1890, Debussy was acquainted with Edmond Bailly, esoteric and oriental scholar, who took part in publishing and selling some of Debussy’s music at his bookstore L’Art Indépendeant. 60 In 1902, Debussy met Louis Laloy, an ethnomusicologist and music critic who eventually became Debussy’s most trusted friend and encouraged his use of Oriental themes.61 After the Universal Exposition in 1889, Debussy had another opportunity to listen to a Gamelan orchestra 11 years later in 1900. -

Richard Goode, Piano

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, January 19, 2014, 3pm Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Préludes, Book I (1909–1910) Zellerbach Hall Danseuses de Delphes Voiles Le vent dans la plaine Richard Goode, piano Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir Les collines d’Anacapri Des pas sur la neige Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest PROGRAM La fille aux cheveux de lin La sérénade interrompue La Cathédrale engloutie La danse de Puck Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) From On an Overgrown Path (1901–1911) Minstrels Our Evenings A Blown-Away Leaf The program is subject to change. Come with Us! Good Night! Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837) Lebhaft Innig Mit humor Ungeduldig Einfach Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ Sehr rasch 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Nicht schnell Frisch This concert is dedicated to the memory of Donald Glaser (1926–2013). Lebhaft Balladenmäßig — Sehr rasch Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Einfach Mit Humor Wild und lustig Zart und singend Frisch Mit gutem Humor Wie aus der Ferne Nicht schnell INTERMISSION 2 3 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) birthday. “I would bind Jenůfa simply with the anguish”) and In Tears (“crying with a smile”). Linda Siegel described as vacillating between Selections from On an Overgrown Path black ribbon of the long illness, suffering and After On an Overgrown Path was published in “fits of depression with complete loss of reality laments of my daughter, Olga,” Janáček con- 1911, Janáček composed a second series of aph- and periods of seemingly placid adjustment to Composed in 1901–1902, 1908, and 1911. -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

Summergarden: Pianist Araceli Chacon to Perform

For Immediate Release July 1989 Summergarden PIANIST ARACELI CHACON TO PERFORM DEBUSSY'S PRELUDES Friday and Saturday, July 14 and 15, 7:30 p.m. A special collaboration between The Museum of Modern Art and The Juilliard School, SUMMERGARDEN 1989 presents a free series of concerts examining the music of Claude Debussy (1862-1918) and Bela Bartok (1881-1945). Under the artistic direction of Paul Zukofsky, performances are held at 7:30 p.m. on Friday and Saturday evenings in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The Garden is open from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m. SUMMERGARDEN is made possible by a grant from Mobil. The second SUMMERGARDEN program, on July 14 and 15, features pianist Araceli Chacon performing the following works by Claude Debussy: Preludes, Book I (1910) 1. Danseuses de Delphes 2. Voiles 3. Le Vent dans la plaine 4. Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l'air du soir 5. Les Collines d'Anacapri 6. Des Pas sur la neige 7. Ce qu'a vu le vent d'ouest 8. La Fille aux cheveux de lin 9. La Serenade interrompue 10. La Cathedrale engloutie 11. La Danse de Puck 12. Minstrels Preludes, Book II (1910-13). 13. Brouillards 14. Feuilles mortes 15. La Puerta del vino 16. Les Fees sont d'exquises danseuses - more - Friday and Saturday evenings in the Sculpture Garden of The Museum of Modern Art are made possible by a grant from Mobil 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY. 10019 5486 Tel: 212-708-9850 Cable: MODERNAkl Telex: 62370 MODART - 2 - 17. -

Formulaic Openings in Debussy

Formulaic Openings in Debussy JAMES A. HEPOKOSKI By now it comes as no surprise that much of grows from not merely one, but several syntac- what may at first strike us as innovative in De- tical conventions. On the one hand, Debussy bussy's music was in fact carried out within the perceived the language of Wagner as the most framework of historical precedent and estab- progressive available style, with its motivic or- lished convention. Indeed, tracing the emer- ganization and transformation, harmonic and gence of his personal style from the early works, formal freedom, aperiodic construction, and ex- with their explicit reliance on existing models, plicit seriousness of purpose.' On the other, he to the later works, where the models or conven- inherited by culture and education the set of tions are more tacit, is an issue of fundamental languages of such French contemporaries and musicological importance. Perhaps no com- immediate predecessors as Gounod, Saint- poser of this fin-de-sikcle era exemplifies more Sains, Faur6, Duparc, Chabrier, Franck, and clearly the expressive tension that results from Massenet-languages not untouched by the ex- the forging of a creative language that simulta- ample of Wagner (and Liszt), but ones more con- neously works within a received tradition and servative in their melodic emphasis and perio- strives for radical originality. dicity, even while they admitted considerable The question of the composer's development harmonic experimentation, particularly in the is particularly complex, because his music area of modality. Debussy's early works blend in differing proportions the existing German Notes for this article begin on page 57. -

Richard Goode, Piano

Sunday, April 22, 2018, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Richard Goode, piano PROGRAM William Byrd (c. 1539/40 or 1543 –1623) Two Pavians and Galliardes from My Ladye Nevells Booke (1591) the seconde pavian the galliarde to the same the third pavian the galliarde to the same Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 –1750) English Suite No. 6 in D minor, BWV 811 (1715 –1720) Prelude Allemande Courante Sarabande - Double Gavotte I Gavotte II Gigue Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 –1827) Sonata No. 28 in A Major, Op. 101 (1815 –16) Etwas lebhaft, und mit der innigsten Empfindung. Allegretto, ma non troppo Lebhaft. Marschmäßig. Vivace alla Marcia Langsam und sehnsuchtsvoll. Adagio, ma non troppo, con affetto Geschwind, doch nicht zu sehr und mit Entschlossenheit. Allegro INTERMISSION Claude Debussy (1862 –1918) Préludes from Book Two (1912 –13) Brouillards—Feuilles mortes—La puerta del Vino—Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses— Bruyères—“Général Lavine” – excentric— La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune— Ondine—Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C.— Canope—Les tierces alternées—Feux d’artifice Richard Goode records for Nonesuch Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 7 PROGRAM NOTES William Byrd Among Byrd’s most significant achievements Selections from My Ladye Nevells Booke was the raising of British music for the virginal, William Byrd was not only the greatest com - the small harpsichord favored in England, to poser of Elizabethan England, but also one of a mature art, “kindling it,” according to Joseph its craftiest politicians. At a time