Claude Debussy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Booklet

552127-28bk VBO Debussy 10/2/06 8:40 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Nocturnes II. Fêtes . .. 6:56 2 String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 10 I. Animé et très décidé . 6:11 3 Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune . 10:29 4 Estampes III. Jardins sous la pluie . 3:43 5 Cello Sonata in D minor I. Prologue . 4:25 6 Suite bergamasque III. Clair de lune . 4:26 7 Violin Sonata in G minor II. Intermède: fantastique et léger . 4:17 8 24 Préludes No. 8. La fille aux cheveux de lin . 2:14 9 La Mer II. Jeux de vagues . 7:29 0 Pelléas et Melisande Act III Scene 1 . 14:22 ! 24 Préludes No. 12. Minstrels . 2:05 @ Rapsodie arabe for Alto Saxophone and Orchestra . 10:50 Total Timing . 78:00 CD2 1 Images II. Iberia . 21:43 2 24 Préludes No. 10. La cathédrale engloutie . 5:47 3 Marche écossaise sur un thème populaire . 6:10 4 Images I I. Reflets dans l’eau . 5:15 5 Rêverie . 3:50 6 L’isle joyeuse . 5:29 7 La Mer I. De l’aube à midi sur la mer . 9:18 8 La plus que lente . 4:44 9 Danse sacrée et danse profane II. Danse profane . 5:16 0 Two Arabesques Arabesque No. 1 . 5:05 ! Children’s Corner VI. Golliwogg’s Cake-walk . 3:09 Total Timing . 76:17 FOR FULL LIST OF DEBUSSY RECORDINGS WITH ARTIST DETAILS AND FOR A GLOSSARY OF MUSICAL TERMS PLEASE GO TO WWW.NAXOS.COM 552127-28bk VBO Debussy 10/2/06 8:40 PM Page 2 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) Children’s Corner VI. -

Liner Notes (PDF)

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

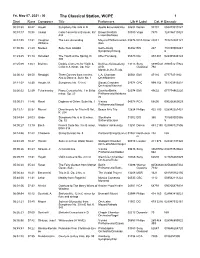

Item # Artist/Ensemble Album Title Quantity

Here at the Mary Pappert School of Music, our prestigious faculty are not only exemplary teachers, but are also active performers. Below are recordings available for purchase by many of these faculty members. Please print this form, indicate which CDs you would like to purchase, and mail along with a check (payable to Duquesne University) to: ATTN: Kathy Ingold Unless otherwise marked: Mary Pappert School of Music Duquesne University Single discs are $15. 00. 600 Forbes Avenue Double disc sets are $25.00. Pittsburgh, PA 15282 Shipping is $2.00 per CD up to $6.00. Please indicate each CD being ordered on a separate line. Item numbers are listed with each CD on the following pages. Item # Artist/Ensemble Album Title Quantity Total Number of single CDs ____________ X $15.00 = _______________ Total Number of double CDs ____________ X $25.00 = _______________ Total Number of individually priced CDs____________ X $____________ = _______________ Shipping ($2.00 per CD, maximum $6.00) =_______________ Mailing Address Grand Total =$_______________ Name:_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address:_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City:___________________________________________________________________State:________________Zip:______________________ For additional information -

ABSTRACT Final

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE BREADTH OF CHOPIN’S INFLUENCE ON FRENCH AND RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC OF THE LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURIES Jasmin Lee, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen School of Music Frederic Chopin’s legacy as a pianist and composer served as inspiration for generations of later composers of piano music, especially in France and Russia. Singing melodies, arpeggiated basses, sensitivity to sonorities, the use of rubato, pedal points, and the full range of the keyboard, plus the frequent use of character pieces as compositional forms characterize Chopin’s compositional style. Future composers Claude Debussy, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Nikolai Medtner, Gabriel Faure, and Maurice Ravel each paid homage to Chopin and his legacy by incorporating and enhancing aspects of his writing style into their own respective works. Despite the disparate compositional trajectories of each of these composers, Chopin’s influence on the development of their individual styles is clearly present. Such influence served as one of the bases for Romantic virtuoso works that came to predominate the late 19th and early 20th century piano literature. This dissertation was completed by performing selected works of Claude Debussy, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Gabriel Faure, Nikolai Medtner, and Maurice Ravel, in three recitals at the Gildenhorn Recital Hall in the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center of the University of Maryland. Compact Disc recordings of the recital are housed -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

Solo List and Reccomended List for 02-03-04 Ver 3

Please read this before using this recommended guide! The following pages are being uploaded to the OSSAA webpage STRICTLY AS A GUIDE TO SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LITERATURE. In 1999 there was a desire to have a required list of solo and ensemble literature, similar to the PML that large groups are required to perform. Many hours were spent creating the following document to provide “graded lists” of literature for every instrument and voice part. The theory was a student who made a superior rating on a solo would be required to move up the list the next year, to a more challenging solo. After 2 years of debating the issue, the music advisory committee voted NOT to continue with the solo/ensemble required list because there was simply too much music written to confine a person to perform from such a limited list. In 2001 the music advisor committee voted NOT to proceed with the required list, but rather use it as “Recommended Literature” for each instrument or voice part. Any reference to “required lists” or “no exceptions” in this document need to be ignored, as it has not been updated since 2001. If you have any questions as to the rules and regulations governing solo and ensemble events, please refer back to the OSSAA Rules and Regulation Manual for the current year, or contact the music administrator at the OSSAA. 105 SOLO ENSEMBLE REGULATIONS 1. Pianos - It is recommended that you use digital pianos when accoustic pianos are not available or if it is most cost effective to use a digital piano. -

Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 6-4-2018 Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, Vivian, "Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4744. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLVING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF DEBUSSY’S PIANO PRELUDES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The Department of Music and Dramatic Arts by Vivian Buchanan B.M., New England Conservatory of Music, 2016 August 2018 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..iii Chapter 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………… 1 2. The Welte-Mignon…………………………………………………………. 7 3. The French Harpsichord Tradition………………………………………….18 4. Debussy’s Piano Rolls……………………………………………………....35 5. The Early Debussystes……………………………………………………...52 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………...63 Selected Discography………………………………………………………………..66 Vita…………………………………………………………………………………..67 ii Abstract Between 1910 and 1912 Claude Debussy recorded twelve of his solo piano works for the player piano company Welte-Mignon. Although Debussy frequently instructed his students to play his music exactly as written, his own recordings are rife with artistic liberties and interpretive freedom. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, May 07, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 30:47 Haydn Symphony No. 042 in D Apollo Ensemble/Hsu 02698 Dorian 90191 053479019127 00:33:1710:38 Vivaldi Cello Concerto in B minor, RV Brown/Scottish 03080 Virgo 7873 724356110328 424 Ensemble/Rees 00:44:5514:31 Vaughan The Lark Ascending Meyers/Philharmonia/L 03876 RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 Williams itton 01:00:5621:29 Nielsen Suite from Aladdin Gothenburg 06392 BIS 247 731859000247 Symphony/Chung 6 01:23:2501:14 Schubert The Youth at the Spring, D. Otter/Forsberg 05373 DG 453 481 028945348124 300 01:25:3933:03 Brahms Double Concerto for Violin & Bell/Isserlis/Academy 13113 Sony 88985321 889853217922 Cello in A minor, Op. 102 of St. Classical 792 Martin-in-the-Fields 02:00:1209:50 Respighi Three Dances from Ancient L.A. Chamber 00561 EMI 47116 07777471162 Airs & Dances, Suite No. 1 Orch/Marriner 02:11:02 14:30 Haydn, M. Symphony No. 12 in G Slovak Chamber 02578 CPO 999 154 761203915422 Orchestra/Warchal 02:26:3232:29 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Gavrilov/Berlin 02074 EMI 49632 077774963220 minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Ashkena zy 03:00:3111:46 Ravel Daphnis et Chloe: Suite No. 1 Vienna 04578 RCA 68600 090266860029 Philharmonic/Maazel 03:13:1720:37 Mozart Divertimento for Trio in B flat, Beaux Arts Trio 12824 Philips 422 700 028942251427 K. 254 03:34:5424:03 Gade Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Stockholm 01002 BIS 355 731859000356 Op. -

L'isle Joyeuse

Composing with Prototypes: Charting Debussy's L'Isle joyeuse Matthew Brown Imagine two scenarios. The first (SI) involves a short, rather crusty, middle-aged composer. A neighbor has just knocked on his door. The composer sits at his piano and plays a short motive - three eighth-note Gs followed by a half-note Ek He decides to add a fifth note. He tries an At, but it doesn't sound right. Next, he tries a Bt; that note doesn't work either. After testing every possibility, he finally picks F. Over the next few months, the short, rather crusty middle-aged composer uses this same strategy to write an entire symphony. The second scenario (S2) is quite different. A small, rather charismatic, young composer is at his desk. He has just returned from an after-dinner walk and is so inspired by the sound of the wind in the trees that he decides to write a new piece. He sits quietly in his chair until the whole thing takes shape in his mind. He then copies out the complete score from memory in one sitting. The small, rather charismatic, young composer eventually goes to bed; the next morning, he sends it off to his publisher without a single alteration. Although both scenarios are utterly implausible - they are straw men constructed for argument's sake - it is not hard to put names to them. SI captures the popular image of Beethoven. From eyewitness reports as well as from the composer's own letters and musical manuscripts, Beethoven is often remembered for the way in which he labored over his scores, meticulously reworking them over many years. -

Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ Edition of French Piano Music, Part II, the Ulti- Mate Collection

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part II The Ultimate Collection Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part II, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Contents of this CD-ROM (click on a composer/category to go to that section of the Table of Contents) DEBUSSY FAURÉ SOLO PIANO SOLO PIANO PIANO FOUR-HANDS PIANO FOUR-HANDS TWO PIANOS The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 CLAUDE DEBUSSY Pièce pour Piano (Morceau de Concours) SOLO PIANO L’isle Joyeuse (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) Masques Deux Arabesques Images, Book I Ballade I. Reflets dans l’Eau Rêverie II. Hommage à Rameau Suite Bergamasque III. Mouvement I. Prélude Children’s Corner II. -

CLAUDE DEBUSSY | SEGMENT LIST © HNH International

CLAUDE DEBUSSY | SEGMENT LIST © HNH International “I could not do without his music. It is my oxygen.” (Francis Poulenc on Debussy) A unique voice in classical music, Claude Debussy exercised widespread influence over later generations of composers, both in his native France and elsewhere, including Messiaen, Cage and Bartók. His music combines late nineteenth- century Romanticism with a soundscape that exudes evocative imagery. This catalogue contains an impressive collection of works by this master composer: piano music, ranging from his ever-popular Clair de lune to the light-hearted Children’s Corner Suite; examples of his influential orchestral music, including Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun and La Mer; the exquisite opera Pelléas et Mélisande, and much more. © 2018 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 1 of 2 LABEL CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS UPC A Musical Journey DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 2.110544 FRANCE: A Musical Tour of Provence Various Artists 747313554454 (1862–1918) Music by Debussy and Ravel [DVD] DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.556663 BEST OF DEBUSSY Various Artists 0730099666329 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Cello Recital – Cello Sonata Tatjana Vassiljeva, Cello / Naxos 8.555762 0747313576227 (1862–1918) (+STRAVINSKY / BRITTEN / DUTILLEUX) Yumiko Arabe, Piano DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.556788 Chill With Debussy Various Artists 0730099678827 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Clair de lune and Other Piano Favorites • Naxos 8.555800 Francois-Joël Thiollier, Piano 0747313580026 (1862–1918) Arabesques • Reflets dans l'eau DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.509002 Complete Orchestral Works [9CDs Boxed Set] Various Artists 747313900237 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Early Works for Piano Duet – Naxos 8.572385 Ivo Haah, Adrienne Soos, Piano 747313238576 (1862–1918) Printemps • Le triomphe de Bacchus • Symphony in B Minor DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.578077-78 Easy-Listening Piano Classics (+RAVEL) [2CDs] Various Artists 747313807772 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.572472 En blanc et noir (+MESSIAEN) Håkon Austbø, Ralph van Raat, Piano 747313247271 (1862–1918) Four-Hand Piano Music, Vol. -

Fin De La Belle Epoque Programme First Proof.Indd

1 FIN DE LA BELLE ÉPOQUE Our keyboard festival this year commemorates the death of Claude Debussy with a performance of the complete Préludes for piano, interspersed with movements of Louis Vierne’s Symphony no 3 for organ. All of this together with pieces from the years of 1909–1913 played by pianists, organists and collaborative pianists and their partners, forms our celebration of the final years of the Belle Époque, which ended at the outbreak of the First World War. Professor Vanessa Latarche Chair of International Keyboard Studies and Head of Keyboard Associate Director for Partnerships in China Royal College of Music This event will be streamed live at www.rcm.ac.uk/live The Senior Common Room will be open 10.30am–6pm serving a range of sandwiches, snacks and beverages. Special thanks must be given to the following people for their support in the organisation of the festival. Thank you everyone! Ian Jones Deputy Head of Keyboard David Graham Professor in Charge of Organ Roger Vignoles Prince Consort Professor of Piano Accompaniment Simon Lepper Piano Accompaniment Co-ordinator Chris Moulton Head of Keyboard Technical Services Alex Beattie Chinese Partnerships and Faculty Officer (Keyboard and Composition) Welcome to the Royal College of Music. For the benefit of musicians and audience members, please turn off your mobile phone. Photographs may only be taken during applause following a performance and filming, recording and commercial photography is not permitted without prior written permission. The RCM films many events and by attending you consent to any photography or recording. See www.rcm.ac.uk for our Public Recording Policy.