Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

2015 49Th Congress, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

Applied ethology 2015: Ethology for sustainable society ISAE2015 Proceedings of the 49th Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology 14-17 September 2015, Sapporo Hokkaido, Japan Ethology for sustainable society edited by: Takeshi Yasue Shuichi Ito Shigeru Ninomiya Katsuji Uetake Shigeru Morita Wageningen Academic Publishers Buy a print copy of this book at: www.WageningenAcademic.com/ISAE2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned. Nothing from this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a computerised system or published in any form or in any manner, including electronic, mechanical, reprographic or photographic, without prior written permission from the publisher: Wageningen Academic Publishers P.O. Box 220 EAN: 9789086862719 6700 AE Wageningen e-EAN: 9789086868179 The Netherlands ISBN: 978-90-8686-271-9 www.WageningenAcademic.com e-ISBN: 978-90-8686-817-9 [email protected] DOI: 10.3920/978-90-8686-817-9 The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from them remain First published, 2015 the responsibility of the authors. The publisher is not responsible for possible © Wageningen Academic Publishers damages, which could be a result of content The Netherlands, 2015 derived from this publication. ‘Sustainability for animals, human life and the Earth’ On behalf of the Organizing Committee of the 49th Congress of ISAE 2015, I would like to say fully welcome for all of you attendances to come to this Congress at Hokkaido, Japan! Now a day, our animals, that is, domestic, laboratory, zoo, companion, pest and captive animals or managed wild animals, and our life are facing to lots of problems. -

Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan Kiyohito Utsunomiya

Special Feature Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan Kiyohito Utsunomiya Introduction National Railways (JNR) and its successor group of railway operators (the so-called JRs) in the late 1980s often became Japan has well-developed inter-city railway transport, as quasi-public railways funded in part by local government, exemplified by the shinkansen, as well as many commuter and those railways also faced management issues. As a railways in major urban areas. For these reasons, the overall result, approximately 670 km of track was closed between number of railway passengers is large and many railway 2000 and 2013. companies are managed as private-sector businesses However, a change in this trend has occurred in recent integrated with infrastructure. However, it will be no easy task years. Many lines still face closure, but the number of cases for private-sector operators to continue to run local railways where public support has rejuvenated local railways is sustainably into the future. rising and the drop in local railway users too is coming to a Outside major urban areas, the number of railway halt (Fig. 1). users is steadily decreasing in Japan amidst structural The next part of this article explains the system and changes, such as accelerating private vehicle ownership recent policy changes in Japan’s local railways, while and accompanying suburbanization, declining population, the third part introduces specific railways where new and declining birth rate. Local lines spun off from Japanese developments are being seen; the fourth part is a summary. Figure 1 Change in Local Railway Passenger Volumes (Unit: 10 Million Passengers) 55 50 45 Number of Passengers 40 35 30 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Fiscal Year Note: 70 companies excluding operators starting after FY1988 Source: Annual Report of Railway Statistics and Investigation by Railway Bureau Japan Railway & Transport Review No. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Via Underground Passage)

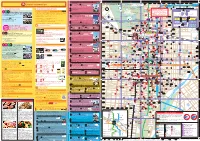

Access from JR Sapporo Station(Via underground passage) ↑To OdoriPark, Sapporo TV tower, Susukino (entertainment district) Hotel Hotel New Monterey Otani Exit No.23 NORTH (Elevator is Edelhof Inn available) Kita 3jo street Subway Toho Exit Rich Line No.19 mond 10 Ticket Ticket Hotel Vending Gate Machine 11 ANA Exit Crowne No.22 Plaza 8 Hotel 7 Exit Exit No.21 No.18 Pachinko parlor 9 HIMAWARI Sosei Exit TOKYU Pachinko River No.23 Department parlor 6 ESTA Store HIMAWARI (Shopping Mall) HOKUREN ←To Ebetsu City (small supermarket) 8 7 Kita 5jo Teine street Coffee JRイン札幌 6 Shop こちらでは DAIMARU 5 ありKomorebiません 4 Department Square 5 Store South Exit Seven-Eleven 3 (Convenience Store) 4 East JR West Ticket Sapporo Ticket Sapporo Stellar Place 2 Gate Station Gate (Shopping Mall) 3 1 ↓To Sapporo Station North Gate, Hokkaido University 1 Immediately after exiting the 2 Take an escalator to the 3 Pass through the door, 4 Turn left at the square towards East Ticket Gate, turn right first basement level of turn right and go straight JR tower east mall and go straight towards south gate. Subway TOHO line a passage until the square. until the end of corridor. Sapporo Station. 5 Walk through the Seven-Eleven, 6 Take an escalator to the 7 Walk thorough a ticket 8 Walk thorough a ticket gate area and turn right along a passage second basement level of vending machine area, on the left-hand side. towards Subway TOHO line Subway TOHO line Sapporo go straight towards Subway (There is no need to enter the gate) Sapporo Station. -

Useful Information

Venture Business Laboratory Useful Information Research Institute for Faculty of Tourist Information Centers Information on Discount Tickets Electronic Science Health Sciences – Around Hokkaido – Bargain Ticket Sapporo Select Hokkaido-Sapporo Tourist Information Center Discount tickets are available for 7 popular facilities of Sapporo (Historical Museum of Hokkaido, A tourist information center located inside JR Sapporo Sapporo TV Tower, Sapporo Hitsujigaoka Observation Hill, Historical Village of Hokkaido, Station, providing information on Hokkaido as a whole, Okurayama Viewing Point Lift, Sapporo Winter Sports Museum, Mt. Moiwa Ropeway). as well as details of JR services. ●Course A Ticket (¥1,980; Elementary school students ¥980) Railway Police Force Honda North Exit Plaza Mt. Moiwa Ropeway + 2 facilities Rent-a-Car Location: West Concourse North Exit, JR Sapporo Nissan Rent-a-Car Bell Plaza Station C-2 ●Course B Ticket (¥1,200; Elementary school students ¥500) (11:00-22:00 last order; ESTA 10F 011-213-2010), Sapporo City University Tel. 011-213-5088 (J / E / C / K) 3 facilities excluding Mt. Moiwa Ropeway. Times Ticket Counter and so on. Soen Campus Kita Kyu Jo Ticket Counter Open year-round 8:30 to 20:00 (School of Nursing) Car Rental (Midori-no-madoguchi) (Midori-no-madoguchi) Tickets outlets Available at the entrances of the facilities above or at the Hokkaido Elementary → Toyota Rental Lease School (JR information desk to 19:00) Sapporo Tourist Information Center (In JR Sapporo Station) Exchange Plaza Shin Sapporo Aeon Sapporo Soen “Elm-no-mori” Shopping Center * The facilities above may be closed on certain days. Please make sure ahead of time. -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Tsuda Sōkichi Vs. Orikuchi Shinobu

Japanese G9040 Graduate Seminar on Premodern Japanese Literature, Spring 2016: Tsuda Sōkichi vs. Orikuchi Shinobu Wednesdays 4:10-6:00pm; 522A Kent Hall David Lurie <[email protected]> Office Hours: Tues. 2-3 & Thurs. 11-12 in 500C Kent Hall Course Rationale: This course treats Tsuda Sōkichi (1873-1961) and Orikuchi Shinobu (1887-1953) as twin titans of twentieth-century scholarship on ancient Japan. In fields as diverse as literature, history of thought, religious studies, mythology, ancient history, poetry, Chinese studies, and drama, their influence remains strong today. Tsuda’s ideas still shape mainstream approaches to Japanese mythology and early historical works, and terms and concepts created by Orikuchi are central to national literary studies (kokubungaku), even if their derivation from his work is often forgotten. It is hard to imagine two scholars more different in approach and style: Tsuda the systematic, skeptical positivist versus Orikuchi the intuitive, speculative romantic. And yet they repeatedly addressed similar questions and problems, and despite Tsuda’s earlier birth and longer life, their periods of greatest productivity (Taishō to early Shōwa, with important codas in the decade or so after the war) also overlapped. Accordingly this syllabus imagines a dialogue between them by juxtaposing selections from key works. Because the oeuvres of Tsuda and Orikuchi are so enormous (put together, their collected works reach 75 volumes) and their interests so varied, it is impossible to provide a systematic overview here. The selection is focused on early Japan, and much has been left out, such as Orikuchi’s work on poetry and drama, or Tsuda’s studies of Buddhism and classical Chinese philosophy. -

Bungei Shunjū in the Early Years and the Emergence

THE EARLY YEARS OF BUNGEI SHUNJŪ AND THE EMERGENCE OF A MIDDLEBROW LITERATURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Minggang Li, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Richard Torrance, Adviser Professor William J. Tyler _____________________________ Adviser Professor Kirk Denton East Asian Languages and Literatures Graduate Program ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the complex relationship that existed between mass media and literature in pre-war Japan, a topic that is largely neglected by students of both literary and journalist studies. The object of this examination is Bungei shunjū (Literary Times), a literary magazine that played an important role in the formation of various cultural aspects of middle-class bourgeois life of pre-war Japan. This study treats the magazine as an organic unification of editorial strategies, creative and critical writings, readers’ contribution, and commercial management, and examines the process by which it interacted with literary schools, mainstream and marginal ideologies, its existing and potential readership, and the social environment at large. In so doing, this study reveals how the magazine collaborated with the construction of the myth of the “ideal middle-class reader” in the discourses on literature, modernity, and nation in Japan before and during the war. This study reads closely, as primary sources, the texts that were published in the issues of Bungei shunjū in the 1920s and 1930s. It then contrasts these texts with ii other texts published by the magazine’s peers and rivals. -

Political and Ritual Usages of Portraits of Japanese

POLITICAL AND RITUAL USAGES OF PORTRAITS OF JAPANESE EMPERORS IN EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES by Yuki Morishima B.A., University of Washington, 1996 B.F.A., University of Washington, 1996 M.S., Boston University, 1999 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Yuki Morishima It was defended on November 13, 2013 and approved by Katheryn Linduff, Professor, Art and Architecture Evelyn Rawski, Professor, History Kirk Savage, Professor, Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Karen Gerhart, Professor, Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Yuki Morishima 2013 iii POLITICAL AND RITUAL USAGES OF PORTRAITS OF JAPANESE EMPERORS IN EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES Yuki Morishima, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation examines portraits of Japanese emperors from the pre-modern Edo period (1603-1868) through the modern Meiji period (1868-1912) by questioning how the socio- political context influenced the production of imperial portraits. Prior to Western influence, pre- modern Japanese society viewed imperial portraits as religious objects for private, commemorative use; only imperial family members and close supporters viewed these portraits. The Confucian notion of filial piety and the Buddhist tradition of tsuizen influenced the production of these commemorative or mortuary portraits. By the Meiji period, however, Western portrait practice had affected how Japan perceived its imperial portraiture. Because the Meiji government socially and politically constructed the ideal role of Emperor Meiji and used the portrait as a means of propaganda to elevate the emperor to the status of a divinity, it instituted controlled public viewing of the images of Japanese emperors. -

East Asia GEOTRACES Workshop Trace Element and Isotope (TEI) Study in the Northwestern Pacific and Its Marginal Seas 16-18 January, 2017 Hotel

East Asia GEOTRACES Workshop Trace Element and Isotope (TEI) study in the Northwestern Pacific and its marginal seas 16-18 January, 2017 Hotel We booked the Hotel MYSTAYS Sapporo Aspen, a very convenient hotel near the Hokkaido University in the city. HOTEL MYSTAYS Sapporo Aspen 4-5, Nishi, Kita 8-jo, Kita-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, 060-0808, Japan Telephone: +81-11-700-2111 Website https://www.mystays.com/en/hotel/hokkaido/hotel-mystays-sapporo-aspen/ ILTS HOTEL MYSTAYS Sapporo Aspen Main Gate of Hokkaido Univ. Sapporo JR Station The location of Hotel, workshop place, Hokkaido Univ. and Sapporo JR station 1 How to get to the HOTEL MYSTAYS Sapporo Aspen Arriving at Hokkaido by plane at the New Chitose Airport From the AIRPORT to Sapporo JR Railway Station Train from New Chitose Airport We strongly recommend catching the 40 minute JR Rapid Airport Line from the Airport to Sapporo Station which runs every 15 minutes. When you arrive at Sapporo Station, it will take about 4 minutes' walk from North Exit of Sapporo Station on the JR Line. The fare of JR Rapid Airport Line is 1070 yean for an adult one way. Bus from New Chitose Airport An express bus, known as the Chuo Bus / Hokuto Kotsu Bus also departs New Chitose Airport bound for Sapporo station and takes approximately 70-90 minutes depending on the traffic condition. It will take about 4 minutes' walk from North Exit of Sapporo Station on the JR Line. The fare of bus is 1030 yean for an adult one way. JR rapid Main Gate of trains Hokkaido Univ.