Arxiv:1803.07237V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

S.I. and Cgs Units

Some Notes on SI vs. cgs Units by Jason Harlow Last updated Feb. 8, 2011 by Jason Harlow. Introduction Within “The Metric System”, there are actually two separate self-consistent systems. One is the Systme International or SI system, which uses Metres, Kilograms and Seconds for length, mass and time. For this reason it is sometimes called the MKS system. The other system uses centimetres, grams and seconds for length, mass and time. It is most often called the cgs system, and sometimes it is called the Gaussian system or the electrostatic system. Each system has its own set of derived units for force, energy, electric current, etc. Surprisingly, there are important differences in the basic equations of electrodynamics depending on which system you are using! Important textbooks such as Classical Electrodynamics 3e by J.D. Jackson ©1998 by Wiley and Classical Electrodynamics 2e by Hans C. Ohanian ©2006 by Jones & Bartlett use the cgs system in all their presentation and derivations of basic electric and magnetic equations. I think many theorists prefer this system because the equations look “cleaner”. Introduction to Electrodynamics 3e by David J. Griffiths ©1999 by Benjamin Cummings uses the SI system. Here are some examples of units you may encounter, the relevant facts about them, and how they relate to the SI and cgs systems: Force The SI unit for force comes from Newton’s 2nd law, F = ma, and is the Newton or N. 1 N = 1 kg·m/s2. The cgs unit for force comes from the same equation and is called the dyne, or dyn. -

CAR-ANS Part 5 Governing Units of Measurement to Be Used in Air and Ground Operations

CIVIL AVIATION REGULATIONS AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES Part 5 Governing UNITS OF MEASUREMENT TO BE USED IN AIR AND GROUND OPERATIONS CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Old MIA Road, Pasay City1301 Metro Manila UNCOTROLLED COPY INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK UNCOTROLLED COPY CAR-ANS PART 5 Republic of the Philippines CIVIL AVIATION REGULATIONS AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES (CAR-ANS) Part 5 UNITS OF MEASUREMENTS TO BE USED IN AIR AND GROUND OPERATIONS 22 APRIL 2016 EFFECTIVITY Part 5 of the Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services are issued under the authority of Republic Act 9497 and shall take effect upon approval of the Board of Directors of the CAAP. APPROVED BY: LT GEN WILLIAM K HOTCHKISS III AFP (RET) DATE Director General Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines Issue 2 15-i 16 May 2016 UNCOTROLLED COPY CAR-ANS PART 5 FOREWORD This Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services (CAR-ANS) Part 5 was formulated and issued by the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP), prescribing the standards and recommended practices for units of measurements to be used in air and ground operations within the territory of the Republic of the Philippines. This Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services (CAR-ANS) Part 5 was developed based on the Standards and Recommended Practices prescribed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as contained in Annex 5 which was first adopted by the council on 16 April 1948 pursuant to the provisions of Article 37 of the Convention of International Civil Aviation (Chicago 1944), and consequently became applicable on 1 January 1949. The provisions contained herein are issued by authority of the Director General of the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines and will be complied with by all concerned. -

Project Physics Reader 4, Light and Electromagnetism

DOM/KEITRESUME ED 071 897 SE 015 534 TITLE Project Physics Reader 4,Light and Electromagnetism. INSTITUTION Harvard 'Jail's, Cambridge,Mass. Harvard Project Physics. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-5-1038 PUB DATE 67 CONTRACT 0M-5-107058 NOTE . 254p.; preliminary Version EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-49.87 DESCRIPTORS Electricity; *Instructional Materials; Li ,t; Magnets;, *Physics; Radiation; *Science Materials; Secondary Grades; *Secondary School Science; *Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Harvard Project Physics ABSTRACT . As a supplement to Project Physics Unit 4, a collection. of articles is presented.. in this reader.for student browsing. The 21 articles are. included under the ,following headings: _Letter from Thomas Jefferson; On the Method of Theoretical Physics; Systems, Feedback, Cybernetics; Velocity of Light; Popular Applications of.Polarized Light; Eye and Camera; The laser--What it is and Doe0; A .Simple Electric Circuit: Ohmss Law; The. Electronic . Revolution; The Invention of the Electric. Light; High Fidelity; The . Future of Current Power Transmission; James Clerk Maxwell, ., Part II; On Ole Induction of Electric Currents; The Relationship of . Electricity and Magnetism; The Electromagnetic Field; Radiation Belts . .Around the Earth; A .Mirror for the Brain; Scientific Imagination; Lenses and Optical Instruments; and "Baffled!." Illustrations for explanation use. are included. The work of Harvard. roject Physics haS ...been financially supported by: the Carnegie Corporation ofNew York, the_ Ford Foundations, the National Science Foundation.the_Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the. United States Office of Education, and Harvard .University..(CC) Project Physics Reader An Introduction to Physics Light and Electromagnetism U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. -

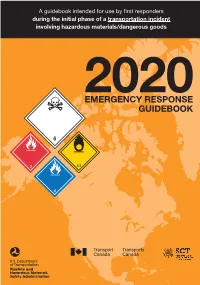

2020 Emergency Response Guidebook

2020 A guidebook intended for use by first responders A guidebook intended for use by first responders during the initial phase of a transportation incident during the initial phase of a transportation incident involving hazardous materials/dangerous goods involving hazardous materials/dangerous goods EMERGENCY RESPONSE GUIDEBOOK THIS DOCUMENT SHOULD NOT BE USED TO DETERMINE COMPLIANCE WITH THE HAZARDOUS MATERIALS/ DANGEROUS GOODS REGULATIONS OR 2020 TO CREATE WORKER SAFETY DOCUMENTS EMERGENCY RESPONSE FOR SPECIFIC CHEMICALS GUIDEBOOK NOT FOR SALE This document is intended for distribution free of charge to Public Safety Organizations by the US Department of Transportation and Transport Canada. This copy may not be resold by commercial distributors. https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/hazmat https://www.tc.gc.ca/TDG http://www.sct.gob.mx SHIPPING PAPERS (DOCUMENTS) 24-HOUR EMERGENCY RESPONSE TELEPHONE NUMBERS For the purpose of this guidebook, shipping documents and shipping papers are synonymous. CANADA Shipping papers provide vital information regarding the hazardous materials/dangerous goods to 1. CANUTEC initiate protective actions. A consolidated version of the information found on shipping papers may 1-888-CANUTEC (226-8832) or 613-996-6666 * be found as follows: *666 (STAR 666) cellular (in Canada only) • Road – kept in the cab of a motor vehicle • Rail – kept in possession of a crew member UNITED STATES • Aviation – kept in possession of the pilot or aircraft employees • Marine – kept in a holder on the bridge of a vessel 1. CHEMTREC 1-800-424-9300 Information provided: (in the U.S., Canada and the U.S. Virgin Islands) • 4-digit identification number, UN or NA (go to yellow pages) For calls originating elsewhere: 703-527-3887 * • Proper shipping name (go to blue pages) • Hazard class or division number of material 2. -

The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors For

NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) – Conversion Factors for General Use Kenneth Butcher Linda Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Technology Services NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors for General Use Editors: Kenneth S. Butcher Linda D. Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Carol Hockert, Chief Weights and Measures Division Technology Services National Institute of Standards and Technology May 2006 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlo M. Gutierrez, Secretary Technology Administration Robert Cresanti, Under Secretary of Commerce for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology William Jeffrey, Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publications 1038 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Pub. 1038, 24 pages (May 2006) Available through NIST Weights and Measures Division STOP 2600 Gaithersburg, MD 20899-2600 Phone: (301) 975-4004 — Fax: (301) 926-0647 Internet: www.nist.gov/owm or www.nist.gov/metric TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................................................................................................................................v -

Physical Quantities: Dimensions and Units

METR 201: Physical Processes Dr. Dave Dempsey in the Atmosphere Physical Quantities: Dimensions and Units Quantities Dimensions MKS and CGS Units MKS: kilograms (kg) mass mass CGS: grams (gm or g) distance, depth, length, MKS: meters (m) height, width distance CGS: centimeters (cm) time time seconds (sec or s) temperature temperature Kelvin (K) and Centigrade (degrees C) MKS: m2 area distance × distance CGS: cm2 distance × distance MKS: m3 volume × distance 3 (i.e., distance3) CGS: cm mass/volume MKS: kg/m3 density (i.e., mass/distance3) CGS: gm/cm3 speed; velocity (motion) (rate of change of distance/time MKS: m/s position) CGS: cm/s acceleration (distance/time)/time (rate of change of an MKS: m/s2 2 object’s velocity with 2 CGS: cm/s respect to time) (i.e., distance/time ) force (“push” or “pull” that can MKS: kg × m/s2 change an object’s mass × acceleration motion) or (Newton) CGS: gm × cm/s2 (Note that weight is just a mass × distance/time2 special case of a force— (dyne) the force of gravity) 1 METR 201: Physical Processes Dr. Dave Dempsey in the Atmosphere Quantities (cont’d) Dimensions MKS and CGS Units pressure force/area MKS: N/ m2 (collective force exerted or 2 2 by random molecular col- (mass or (kg × m/s )/m (Pascal) lisions against each unit of × distance/time2)/area area of an object’s or 2 surroundings) energy/volume CGS: dyne/cm work MKS: Newton x m (force times distance over force × distance or kg × m2/s2 which the force is applied or or Pa × m3 to an object as the object mass × acceleration (Joule) moves under the influence × distance of the force); or CGS: dyne × cm energy pressure × volume or gm × cm2/s2 (the capacity to do work) (erg) energy/time MKS: J/s power or or N × m/s (energy transferred or force × distance/time or kg × (m/s2) x m/s gained or lost per unit or (Watt) time) force × velocity etc. -

Units of Measure Used in International Trade Page 1/57 Annex II (Informative) Units of Measure: Code Elements Listed by Name

Annex II (Informative) Units of Measure: Code elements listed by name The table column titled “Level/Category” identifies the normative or informative relevance of the unit: level 1 – normative = SI normative units, standard and commonly used multiples level 2 – normative equivalent = SI normative equivalent units (UK, US, etc.) and commonly used multiples level 3 – informative = Units of count and other units of measure (invariably with no comprehensive conversion factor to SI) The code elements for units of packaging are specified in UN/ECE Recommendation No. 21 (Codes for types of cargo, packages and packaging materials). See note at the end of this Annex). ST Name Level/ Representation symbol Conversion factor to SI Common Description Category Code D 15 °C calorie 2 cal₁₅ 4,185 5 J A1 + 8-part cloud cover 3.9 A59 A unit of count defining the number of eighth-parts as a measure of the celestial dome cloud coverage. | access line 3.5 AL A unit of count defining the number of telephone access lines. acre 2 acre 4 046,856 m² ACR + active unit 3.9 E25 A unit of count defining the number of active units within a substance. + activity 3.2 ACT A unit of count defining the number of activities (activity: a unit of work or action). X actual ton 3.1 26 | additional minute 3.5 AH A unit of time defining the number of minutes in addition to the referenced minutes. | air dry metric ton 3.1 MD A unit of count defining the number of metric tons of a product, disregarding the water content of the product. -

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurements of Transition Metal Containing Compounds

Magnetic susceptibility measurements of transition metal containing compounds Introduction: Measurements of magnetic properties have been used to characterize a wide range of systems from oxygen, metallic alloys, solid state materials, and coordination complexes containing metals. Most organic and main group element compounds have all the electrons paired and these are diamagnetic molecules with very small magnetic moments. All of the transition metals have at least one oxidation state with an incomplete d subshell. Magnetic measurements, particularly for the first row transition elements, give information about the number of unpaired electrons. The number of unpaired electrons provides information about the oxidation state and electron configuration. The determination of the magnetic properties of the second and third row transition elements is more complex. The magnetic moment is calculated from the magnetic susceptibility, since the magnetic moment is not measured directly. There are several ways to express the degree to which a material acquires a magnetic moment in a field. The magnetic susceptibility per unit volume is defined by: I H where I is the intensity of the magnetization induced in the sample by the external magnetic field, H. The extent of the magnetic induction (I) depends on the sample. The induction may be visualized as an alignment of dipoles and/or by the formation of charge polarization in the sample. H is the strength of the external magnetic field in units of oersteds (Oe). The κ is unitless. Generally, it is more convenient to use mass units, therefore the mass or gram susceptibility is defined as: g d where d is the density of the solid. -

Metric Units.Pdf

Metric Units: (adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metric_system ) CGS centimeter gram second system MKS meter kilogram second system Variants of the metric system Quantity CGS MKS length (l) centimeter (cm) meter (m) Meter = 100 centimeters mass(m) gram (g) kilogram (kg) The kilogram (SI symbol: kg), also known as the kilo, is the base unit of mass in the International time (t) second (s) second System of Units. (kilogram = 1000 gram(g) ) velocity(v) cm/s m/s acceleration (a) cm/s² m/s² 1 dyne = 1 g·cm/s² = 10−5 kg·m/s² = 10−5 Newton force (F) dyne (dyn) newton (N) 1Newton = 1 kg·m/s2 pressure (p) barye (Ba) pascal (Pa) 1 Ba = 0.1 Pascal = 0.1 Newton/m2 = 1 g·cm-1s-2 2 2 −7 energy (W) erg (erg) joule (J) 1 erg = g·cm /s = 10 joules (1 erg = 1 dyne cm = 1 g·cm2/s2) 1 joule = 107 erg power (P) erg/s watt (W) 1 watt = one joule per second (power measures viscosity (µ) poise (p) Pa·s the rate of energy conversion) 1 poise = 1 g·cm-1·s-1 (1 Pascal·s = 1Pa·s = 1 -1 -1 kg·m ·s (the extent to which a fluid resists a tendency to flow) The International System of Units (System international units or SI) is the current international standard metric system and the system most widely used around the world. Mass can be defined as a quantitative measure of an object's resistance to the change of its speed. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications By, and About, James Clerk Maxwell

A Complete Bibliography of Publications by, and about, James Clerk Maxwell Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 10 July 2021 Version 1.35 Title word cross-reference 1=2 [Arm04]. $17.00 [Eve84]. $195 [Buc92]. $195.00 [Hun05a]. $25.00 [Mar99a]. $25.95 [Jam15]. $28.75 [Can90]. $285.00 [Hun05a]. $29.00 [Row05]. 3 [Ive05]. $315.00 [Hun05a]. $38.45 [Har93]. $39.50 [Sto82]. $45.00 [Ber08]. $49.50 [Hun92, Mar93]. $55 [She04a, She04b]. $59.95 [Yos99]. $6.95 [Eve84]. $77.00 [Sto82]. $77.00/$ [Tur83]. $8.95 [Lin71]. $86.25 [Can90]. B [Ive05]. E [Ive05]. [Spr06]. H [Dia94b]. [Spr06]. v [Cle70c]. &c. [Cle73b]. -theorem [Dia94b]. 0 [Cha84, Hun92, Mar99a, Pip99, Pip04, Row05, She04a, She04b]. 0-226-07882-5 [Roc87]. 0-226-07884-1 [Can90]. 0-226-07886-8 [Can90]. 1 2 0-226-87375-7 [Row05]. 0-470-86088-X [Hun06, Pip04]. 0-521-25625-9 [Buc92, Hun05a, Jam91, Seg92]. 0-521-25626-7 [Hun05a]. 0-521-25627-5 [Hun05a]. 0-521-35365-3 [Mar93, Hun92]. 0-521-56102-7 [Yos99, Pip99]. 0-679-43342-2 [Mar99a]. 0-7503-0759-5 [She04a, She04b]. 0-8014-2641-3 [Har93]. 0-85274-563-X [The87]. 0-86228-026-5 [Smi85, Cha84]. 0-86341-101-0 [Hun89]. 0-934223-34-3 [Har96]. -

Phwsical Constants

NASA SP-1012 I ~'(';,., "C .2 L S Y;) ',: <. i~ C UN,':;'. / N'~ S :i if I.; ..;; r- ~. ,- ~ '~ .: ~:" .'::: ;i C. C ~. :...~; ,~ VIS ~: eN C ~3::'1 .... j.<,;:;: ;:',:/3,~ ""O"y" I iIiiw " Il~? i~ I II ~ I•. ~ .. I r I I 1 1 ~. ~ it I t I .' t I ~ 111 III m III Phwsical• Constants- and ~d' F t ~ .llverSI\on'J!B'" · ors ! ~~ ~ *1\'" acIi SECOND REJiVlSI .. 1 ..... I II ~, v, ", i~ m -, ~~hn& NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION NASA SP·7012 THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM OF UNITS PHYSICAL CONSTANTS and CONVERSION FACTORS SECOND REVISION E. A. MECHTL Y University of Illinois tj/S.r .... J&vu· Scientific and Technical Information Office 1973 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION Washington, D.C. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 72-600360 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, .... U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents, domestic postpaid; 35 cents, GPO Bookstore Stock Number 3300-00482 .FOREWORD The International System of Units, Systeme International d'Unites (designated SI in all languages), is the system of units of measurement which has been adopted by 41 of the principal industrial nations of the world which are signatories to the Convention of the Meter. The 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th General Conferences on Weights and Measures (meeting in October of 1960, 1964, 1967, and 1971, respectively) have brought the International System of Units to a state of completeness and coherence which make it increasingly more attractive for all applications. The National Bureau of Standards 01 the United States announced in Administrative Bulletin 64-6 dated February 1964 that- Henceforth it shall be the policy of the National Bureau of Standards to use the units of the International System (SI), as adopted by the Eleventh General Conference on Weights and Measures ..