SI and CGS Units in Electromagnetism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A: Symbols and Prefixes

Appendix A: Symbols and Prefixes (Appendix A last revised November 2020) This appendix of the Author's Kit provides recommendations on prefixes, unit symbols and abbreviations, and factors for conversion into units of the International System. Prefixes Recommended prefixes indicating decimal multiples or submultiples of units and their symbols are as follows: Multiple Prefix Abbreviation 1024 yotta Y 1021 zetta Z 1018 exa E 1015 peta P 1012 tera T 109 giga G 106 mega M 103 kilo k 102 hecto h 10 deka da 10-1 deci d 10-2 centi c 10-3 milli m 10-6 micro μ 10-9 nano n 10-12 pico p 10-15 femto f 10-18 atto a 10-21 zepto z 10-24 yocto y Avoid using compound prefixes, such as micromicro for pico and kilomega for giga. The abbreviation of a prefix is considered to be combined with the abbreviation/symbol to which it is directly attached, forming with it a new unit symbol, which can be raised to a positive or negative power and which can be combined with other unit abbreviations/symbols to form abbreviations/symbols for compound units. For example: 1 cm3 = (10-2 m)3 = 10-6 m3 1 μs-1 = (10-6 s)-1 = 106 s-1 1 mm2/s = (10-3 m)2/s = 10-6 m2/s Abbreviations and Symbols Whenever possible, avoid using abbreviations and symbols in paragraph text; however, when it is deemed necessary to use such, define all but the most common at first use. The following is a recommended list of abbreviations/symbols for some important units. -

EM Concept Map

EM concept map Conservation laws Special relativity EM waves radiation Field laws No Gauss’s law monopoles ConservationMaxwell’s laws magnetostatics electrostatics equations (In vacuum) Faraday’s law Ampere’s law Integral and differential form Radiation effects on matter Continuum model of matter Lorenz force law EM fields in matter Mechanical systems (particles) Electricity and Magnetism PHYS-350: (updated Sept. 9th, (1605-1725 Monday, Wednesday, Leacock 109) 2010) Instructor: Shaun Lovejoy, Rutherford Physics, rm. 213, local Outline: 6537, email: [email protected]. 1. Vector Analysis: Tutorials: Tuesdays 4:15pm-5:15pm, location: the “Boardroom” Algebra, differential and integral calculus, curvilinear coordinates, (the southwest corner, ground floor of Rutherford physics). Office Hours: Thursday 4-5pm (either Lhermitte or Gervais, see Dirac function, potentials. the schedule on the course site). 2. Electrostatics: Teaching assistant: Julien Lhermitte, rm. 422, local 7033, email: Definitions, basic notions, laws, divergence and curl of the electric [email protected] potential, work and energy. Gervais, Hua Long, ERP-230, [email protected] 3. Special techniques: Math background: Prerequisites: Math 222A,B (Calculus III= Laplace's equation, images, seperation of variables, multipole multivariate calculus), 223A,B (Linear algebra), expansion. Corequisites: 314A (Advanced Calculus = vector 4. Electrostatic fields in matter: calculus), 315A (Ordinary differential equations) Polarization, electric displacement, dielectrics. Primary Course Book: "Introduction to Electrodynamics" by D. 5. Magnetostatics: J. Griffiths, Prentice-Hall, (1999, third edition). Lorenz force law, Biot-Savart law, divergence and curl of B, vector Similar books: potentials. -“Electromagnetism”, G. L. Pollack, D. R. Stump, Addison and 6. Magnetostatic fields in matter: Wesley, 2002. -

Gauss' Linking Number Revisited

October 18, 2011 9:17 WSPC/S0218-2165 134-JKTR S0218216511009261 Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications Vol. 20, No. 10 (2011) 1325–1343 c World Scientific Publishing Company DOI: 10.1142/S0218216511009261 GAUSS’ LINKING NUMBER REVISITED RENZO L. RICCA∗ Department of Mathematics and Applications, University of Milano-Bicocca, Via Cozzi 53, 20125 Milano, Italy [email protected] BERNARDO NIPOTI Department of Mathematics “F. Casorati”, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy Accepted 6 August 2010 ABSTRACT In this paper we provide a mathematical reconstruction of what might have been Gauss’ own derivation of the linking number of 1833, providing also an alternative, explicit proof of its modern interpretation in terms of degree, signed crossings and inter- section number. The reconstruction presented here is entirely based on an accurate study of Gauss’ own work on terrestrial magnetism. A brief discussion of a possibly indepen- dent derivation made by Maxwell in 1867 completes this reconstruction. Since the linking number interpretations in terms of degree, signed crossings and intersection index play such an important role in modern mathematical physics, we offer a direct proof of their equivalence. Explicit examples of its interpretation in terms of oriented area are also provided. Keywords: Linking number; potential; degree; signed crossings; intersection number; oriented area. Mathematics Subject Classification 2010: 57M25, 57M27, 78A25 1. Introduction The concept of linking number was introduced by Gauss in a brief note on his diary in 1833 (see Sec. 2 below), but no proof was given, neither of its derivation, nor of its topological meaning. Its derivation remained indeed a mystery. -

On the Covariant Representation of Integral Equations of the Electromagnetic Field

On the covariant representation of integral equations of the electromagnetic field Sergey G. Fedosin PO box 614088, Sviazeva str. 22-79, Perm, Perm Krai, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Gauss integral theorems for electric and magnetic fields, Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction, magnetic field circulation theorem, theorems on the flux and circulation of vector potential, which are valid in curved spacetime, are presented in a covariant form. Covariant formulas for magnetic and electric fluxes, for electromotive force and circulation of the vector potential are provided. In particular, the electromotive force is expressed by a line integral over a closed curve, while in the integral, in addition to the vortex electric field strength, a determinant of the metric tensor also appears. Similarly, the magnetic flux is expressed by a surface integral from the product of magnetic field induction by the determinant of the metric tensor. A new physical quantity is introduced – the integral scalar potential, the rate of change of which over time determines the flux of vector potential through a closed surface. It is shown that the commonly used four-dimensional Kelvin-Stokes theorem does not allow one to deduce fully the integral laws of the electromagnetic field and in the covariant notation requires the addition of determinant of the metric tensor, besides the validity of the Kelvin-Stokes theorem is limited to the cases when determinant of metric tensor and the contour area are independent from time. This disadvantage is not present in the approach that uses the divergence theorem and equation for the dual electromagnetic field tensor. -

Units and Magnitudes (Lecture Notes)

physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek Units and Magnitudes (lecture notes) This lecture has two parts. The first part is mainly a practical guide to the measurement units that dominate the particle physics literature, and culture. The second part is a quasi-philosophical discussion of deep issues around unit systems, including a comparison of atomic, particle ("strong") and Planck units. For a more extended, profound treatment of the second part issues, see arxiv.org/pdf/0708.4361v1.pdf . Because special relativity and quantum mechanics permeate modern particle physics, it is useful to employ units so that c = ħ = 1. In other words, we report velocities as multiples the speed of light c, and actions (or equivalently angular momenta) as multiples of the rationalized Planck's constant ħ, which is the original Planck constant h divided by 2π. 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek In classical physics one usually keeps separate units for mass, length and time. I invite you to think about why! (I'll give you my take on it later.) To bring out the "dimensional" features of particle physics units without excess baggage, it is helpful to keep track of powers of mass M, length L, and time T without regard to magnitudes, in the form When these are both set equal to 1, the M, L, T system collapses to just one independent dimension. So we can - and usually do - consider everything as having the units of some power of mass. Thus for energy we have while for momentum 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek and for length so that energy and momentum have the units of mass, while length has the units of inverse mass. -

On the First Electromagnetic Measurement of the Velocity of Light by Wilhelm Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch

Andre Koch Torres Assis On the First Electromagnetic Measurement of the Velocity of Light by Wilhelm Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch Abstract The electrostatic, electrodynamic and electromagnetic systems of units utilized during last century by Ampère, Gauss, Weber, Maxwell and all the others are analyzed. It is shown how the constant c was introduced in physics by Weber's force of 1846. It is shown that it has the unit of velocity and is the ratio of the electromagnetic and electrostatic units of charge. Weber and Kohlrausch's experiment of 1855 to determine c is quoted, emphasizing that they were the first to measure this quantity and obtained the same value as that of light velocity in vacuum. It is shown how Kirchhoff in 1857 and Weber (1857-64) independently of one another obtained the fact that an electromagnetic signal propagates at light velocity along a thin wire of negligible resistivity. They obtained the telegraphy equation utilizing Weber’s action at a distance force. This was accomplished before the development of Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory of light and before Heaviside’s work. 1. Introduction In this work the introduction of the constant c in electromagnetism by Wilhelm Weber in 1846 is analyzed. It is the ratio of electromagnetic and electrostatic units of charge, one of the most fundamental constants of nature. The meaning of this constant is discussed, the first measurement performed by Weber and Kohlrausch in 1855, and the derivation of the telegraphy equation by Kirchhoff and Weber in 1857. Initially the basic systems of units utilized during last century for describing electromagnetic quantities is presented, along with a short review of Weber’s electrodynamics. -

Weberˇs Planetary Model of the Atom

Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Bearbeitet von Andre Koch Torres Assis, Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr 1. Auflage 2011. Taschenbuch. 184 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 8424 0241 6 Format (B x L): 17 x 22 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Physik, Astronomie > Physik Allgemein schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Figure 0.1: Wilhelm Eduard Weber (1804–1891) Foto: Gudrun Wolfschmidt in der Sternwarte in Göttingen 2 Nuncius Hamburgensis Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften Band 19 Andre Koch Torres Assis, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr and Gudrun Wolfschmidt Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom Ed. by Gudrun Wolfschmidt Hamburg: tredition science 2011 Nuncius Hamburgensis Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften Hg. von Gudrun Wolfschmidt, Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Mathematik und Technik, Universität Hamburg – ISSN 1610-6164 Diese Reihe „Nuncius Hamburgensis“ wird gefördert von der Hans Schimank-Gedächtnisstiftung. Dieser Titel wurde inspiriert von „Sidereus Nuncius“ und von „Wandsbeker Bote“. Andre Koch Torres Assis, Karl Heinrich Wiederkehr and Gudrun Wolfschmidt: Weber’s Planetary Model of the Atom. Ed. by Gudrun Wolfschmidt. Nuncius Hamburgensis – Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Band 19. Hamburg: tredition science 2011. Abbildung auf dem Cover vorne und Titelblatt: Wilhelm Weber (Kohlrausch, F. (Oswalds Klassiker Nr. 142) 1904, Frontispiz) Frontispiz: Wilhelm Weber (1804–1891) (Feyerabend 1933, nach S. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

S.I. and Cgs Units

Some Notes on SI vs. cgs Units by Jason Harlow Last updated Feb. 8, 2011 by Jason Harlow. Introduction Within “The Metric System”, there are actually two separate self-consistent systems. One is the Systme International or SI system, which uses Metres, Kilograms and Seconds for length, mass and time. For this reason it is sometimes called the MKS system. The other system uses centimetres, grams and seconds for length, mass and time. It is most often called the cgs system, and sometimes it is called the Gaussian system or the electrostatic system. Each system has its own set of derived units for force, energy, electric current, etc. Surprisingly, there are important differences in the basic equations of electrodynamics depending on which system you are using! Important textbooks such as Classical Electrodynamics 3e by J.D. Jackson ©1998 by Wiley and Classical Electrodynamics 2e by Hans C. Ohanian ©2006 by Jones & Bartlett use the cgs system in all their presentation and derivations of basic electric and magnetic equations. I think many theorists prefer this system because the equations look “cleaner”. Introduction to Electrodynamics 3e by David J. Griffiths ©1999 by Benjamin Cummings uses the SI system. Here are some examples of units you may encounter, the relevant facts about them, and how they relate to the SI and cgs systems: Force The SI unit for force comes from Newton’s 2nd law, F = ma, and is the Newton or N. 1 N = 1 kg·m/s2. The cgs unit for force comes from the same equation and is called the dyne, or dyn. -

SI and CGS Units in Electromagnetism

SI and CGS Units in Electromagnetism Jim Napolitano January 7, 2010 These notes are meant to accompany the course Electromagnetic Theory for the Spring 2010 term at RPI. The course will use CGS units, as does our textbook Classical Electro- dynamics, 2nd Ed. by Hans Ohanian. Up to this point, however, most students have used the International System of Units (SI, also known as MKSA) for mechanics, electricity and magnetism. (I believe it is easy to argue that CGS is more appropriate for teaching elec- tromagnetism to physics students.) These notes are meant to smooth the transition, and to augment the discussion in Appendix 2 of your textbook. The base units1 for mechanics in SI are the meter, kilogram, and second (i.e. \MKS") whereas in CGS they are the centimeter, gram, and second. Conversion between these base units and all the derived units are quite simply given by an appropriate power of 10. For electromagnetism, SI adds a new base unit, the Ampere (\A"). This leads to a world of complications when converting between SI and CGS. Many of these complications are philosophical, but this note does not discuss such issues. For a good, if a bit flippant, on- line discussion see http://info.ee.surrey.ac.uk/Workshop/advice/coils/unit systems/; for a more scholarly article, see \On Electric and Magnetic Units and Dimensions", by R. T. Birge, The American Physics Teacher, 2(1934)41. Electromagnetism: A Preview Electricity and magnetism are not separate phenomena. They are different manifestations of the same phenomenon, called electromagnetism. One requires the application of special relativity to see how electricity and magnetism are united. -

DIMENSIONS and UNITS to Get the Value of a Quantity in Gaussian Units, Multiply the Value Ex- Pressed in SI Units by the Conversion Factor

DIMENSIONS AND UNITS To get the value of a quantity in Gaussian units, multiply the value ex- pressed in SI units by the conversion factor. Multiples of 3 intheconversion factors result from approximating the speed of light c =2.9979 1010 cm/sec × 3 1010 cm/sec. ≈ × Dimensions Physical Sym- SI Conversion Gaussian Quantity bol SI Gaussian Units Factor Units t2q2 Capacitance C l farad 9 1011 cm ml2 × m1/2l3/2 Charge q q coulomb 3 109 statcoulomb t × q m1/2 Charge ρ coulomb 3 103 statcoulomb 3 3/2 density l l t /m3 × /cm3 tq2 l Conductance siemens 9 1011 cm/sec ml2 t × 2 tq 1 9 1 Conductivity σ siemens 9 10 sec− 3 ml t /m × q m1/2l3/2 Current I,i ampere 3 109 statampere t t2 × q m1/2 Current J, j ampere 3 105 statampere 2 1/2 2 density l t l t /m2 × /cm2 m m 3 3 3 Density ρ kg/m 10− g/cm l3 l3 q m1/2 Displacement D coulomb 12π 105 statcoulomb l2 l1/2t /m2 × /cm2 1/2 ml m 1 4 Electric field E volt/m 10− statvolt/cm t2q l1/2t 3 × 2 1/2 1/2 ml m l 1 2 Electro- , volt 10− statvolt 2 motance EmfE t q t 3 × ml2 ml2 Energy U, W joule 107 erg t2 t2 m m Energy w, ϵ joule/m3 10 erg/cm3 2 2 density lt lt 10 Dimensions Physical Sym- SI Conversion Gaussian Quantity bol SI Gaussian Units Factor Units ml ml Force F newton 105 dyne t2 t2 1 1 Frequency f, ν hertz 1 hertz t t 2 ml t 1 11 Impedance Z ohm 10− sec/cm tq2 l 9 × 2 2 ml t 1 11 2 Inductance L henry 10− sec /cm q2 l 9 × Length l l l meter (m) 102 centimeter (cm) 1/2 q m 3 Magnetic H ampere– 4π 10− oersted 1/2 intensity lt l t turn/m × ml2 m1/2l3/2 Magnetic flux Φ weber 108 maxwell tq t m m1/2 Magnetic -

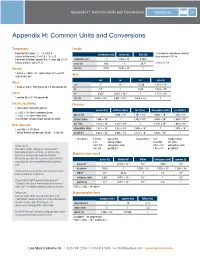

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités).