The Freedom of the City, Or How Reality Contaminates Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Obra Dramática De Brian Friel Y Su Repercusión En España

DEPARTAMENT DE FILOLOGIA ANGLESA I ALEMANYA ÉRASE UNA VEZ BALLYBEG: LA OBRA DRAMÁTICA DE BRIAN FRIEL Y SU REPERCUSIÓN EN ESPAÑA. MARÍA GAVIÑA COSTERO UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA Servei de Publicacions 2011 Aquesta Tesi Doctoral va ser presentada a València el dia 6 de maig de 2011 davant un tribunal format per: - Dra. Teresa Caneda Cabrera - Dr. Vicent Montalt i Resurreció - Dra. Pilar Ezpeleta Piorno - Dra. Laura Monrós Gaspar - Dra. Ana R. Calero Valera Va ser dirigida per: Dr. Miguel Teruel Pozas ©Copyright: Servei de Publicacions María Gaviña Costero I.S.B.N.: 978-84-370-8215-8 Edita: Universitat de València Servei de Publicacions C/ Arts Gràfiques, 13 baix 46010 València Spain Telèfon:(0034)963864115 ÉRASE UA VEZ BALLYBEG: LA OBRA DRAMÁTICA DE BRIAN FRIEL Y SU REPERCUSIÓN EN ESPAÑA TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: María Gaviña Costero Director: Dr. Miguel Teruel Pozas I AGRADECIMIETOS Cuando enferma en el hospital de Omagh, en 1989, una amiga francesa me prestó un texto de un autor “local” para aligerar mi tedio, no podía ni imaginar lo que este hombre iba a significar para mí años más tarde. Christine fue la primera de una larga lista de personas involucradas en esta tesis. En todos estos años de trabajo son muchos los que se han visto damnificados por mi obsesión con Brian Friel, tanto es así que algunos se pueden considerar ya auténticos expertos. Sin la ayuda de todos ellos habría tirado la toalla en innumerables ocasiones. En primer lugar quiero agradecer a mi director de tesis, el doctor Miguel Teruel, que me propusiera un tema que me iba a apasionar según avanzaba en su estudio, y aún más, que me motivara todos estos años a continuar porque el trabajo merecía la pena, a pesar de todas mis dudas y vacilaciones. -

Copyright by Judith Hazel Howell 2011

Copyright by Judith Hazel Howell 2011 The Report Committee for Judith Hazel Howell Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Waiting for the Truth: A Re-examination of Four Representations of Bloody Sunday After the Saville Inquiry APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Elizabeth Cullingford Wayne Lesser Waiting for the Truth: A Re-examination of Four Representations of Bloody Sunday After the Saville Inquiry by Judith Hazel Howell, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Abstract Waiting for the Truth: A Re-examination of Four Representations of Bloody Sunday After the Saville Inquiry Judith Hazel Howell, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Elizabeth Cullingford On January 30, 1972, in Derry, Northern Ireland, British soldiers opened fire on Irish citizens participating in a peaceful civil rights march, killing thirteen men and injuring as many others. This event, called “Bloody Sunday,” was the subject of two formal inquiries by the British government, one conducted by Lord Widgery in 1972 that exonerated the British soldiers and one led by Lord Saville, which published its findings in June 2010 and found the British troops to be at fault. Before the second investigation gave its report, a number of dramatic productions had contradicted the official British version of events and presented the Irish point of view. Two films and two plays in particular—the drama The Freedom of the City (1973), the filmed docudramas Bloody Sunday and Sunday (both 2002), and the documentary theater production Bloody Sunday: Scenes from the Saville Inquiry (2005)—were aimed at audiences that did not recognize the injustices that took place in Derry. -

Freeman Journal 2016

68934 Freeman cover_Freeman cover & inners 29/06/2016 06:26 Page 2 THE FREEMAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL AND PROGRAMME of the GUILD OF FREEMEN OF THE CITY OF LONDON The Master 2015-2016 LADY COOKSEY OBE DL The Master 2016-2017 ALDERMAN SIR DAVID WOOTTON JUNE 2016 NUMBER 165 68934 Freeman cover_Freeman cover & inners 29/06/2016 06:26 Page 3 THE GUILD OF FREEMEN OF THE CITY OF LONDON “O, Most Gracious Lord, Defend Thy Citizens of London” Centenary Master Her Royal Highness The Princess Royal Patron The Right Honourable The Lord Mayor, The Lord Mountevans Honorary Member of the Guild His Majesty King Michael I of Romania F The Court of Assistants 2015/2016 Master Lady Cooksey OBE DL Wardens Senior Warden Alderman Sir David Wootton Renter Warden Peter Allcard, Esq. Junior Warden John Barber, Esq., DL Under Warden Mrs Elizabeth Thornborough Past Masters Terry Nemko, Esq., JP; Sir Gavyn Arthur; Anthony Woodhead, Esq., CBE; Mrs Anne Holden; Dr John Smail, JP Court Assistants Anthony Bailey, Esq., OBE GCSS; Neil Redcliffe, Esq., JP; Alderman John Garbutt, JP; David Wilson, Esq.; Mrs Ann-Marie Jefferys; Christopher Walton, Esq.; Councillor Lisa Rutter; Anthony Miller, Esq., MBE; Adrian Waddingham, Esq., CBE; Councillor Christopher Hayward, Esq., CC; Ms Dorothy Saul-Pooley; Alderman Timothy Hailes, JP Past Masters Emeritus Harold Gould, Esq., OBE JP DL; Sir Anthony Grant; Dr John Breen; Rex Johnson, Esq.; Sir Clive Martin, OBE TD DL; Joseph Byllam-Barnes, Esq.; David Irving, Esq.; Richard Agutter, Esq., JP; Mrs Barbara Newman, CBE CC; Gordon Gentry, Esq.; Mrs Pauline Halliday, OBE; Don Lunn, Esq. -

Martine Pelletier University of Tours, France

Brian Friel: the master playwright 135 BRIAN FRIEL: THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHT Martine Pelletier University of Tours, France Abstract: Brian Friel has long been recognized as Ireland’s leading playwright. His work for the theatre spans almost fifty years and his reputation has expanded well beyond Ireland. In January 2009 Friel turned eighty and only a few months before, his adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, opened at the Gate Theatre Dublin on 30th September 2008. This article will first provide a survey of Brian Friel’s remarkable career, trying to assess his overall contribution to Irish theatre, before looking at his various adaptations to finally focus on Hedda Gabler, its place and relevance in the author’s canon. Keywordsds: Brian Friel, Irish Theatre, Hedda Gabler, Adaptation, Ireland. Brian Friel has long been recognized as the leading playwright in contemporary Ireland. His work for the theatre spans almost fifty years and his reputation has expanded beyond Ireland and outside the English-speaking world, where several of his plays are regularly produced, studied and enjoyed by a wide range of audiences and critics. In January 2009, Brian Friel turned eighty and only a few months before, his adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler,1 opened at the Gate Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 58 p. 135-156 jan/jun. 2010 136 Martine Pelletier Theatre Dublin on 30th September 2008 as part of the Dublin Theatre Festival. This article will first provide a survey of Brian Friel’s remarkable career, trying to assess his overall contribution to Irish theatre, before looking at his various adaptations to finally focus on Hedda Gabler, its place and relevance in the author’s canon. -

Bloody Sunday Web Quest

Sunday Bloody Sunday Web Quest. Historical, sociosocio----culturalcultural and political issues __________________________________________________________ Answer the following questions based on the song Sunday Bloody Sunday . (link to lyrics and the song) Look and find the information you need to answer the questions below (on the web or in printed press). Please make sure you include the references used at the end of each question. Question 1: What does “Bloody Sunday” refer to? Demonstration in Londonderry (Derry), Northern Ireland, on Sunday, January 30, 1972, by Roman Catholic civil rights supporters that turned violent when British paratroopers opened fire, killing 13 and injuring 14 others (one of the injured later died). Question 2: When and where did the incident happen? In Derry, Northern Ireland, on 30 January 1972 Question 3: Who were the parties involved in the massacre? 26 civil rights protesters and the members of the 1st Battalion of the British Parachute Regiment during a Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association march in the Bogside area of the city. Question 4: Which were the political issues lying behind the incident? The Protestant-Catholic conflict in Northern Ireland Question 5: Why is it remembered as one of the most significant events in relation to the troubles in Northern Ireland? Because it was carried out by the army and not paramilitaries, and in full public and press view Question 6: How many people were killed? Who were they? What did they all have in common? 13 people, six of whom were minors, died immediately, while the death of another person 4½ months later has been attributed to the injuries he received on the day: John (Jackie) Duddy (17), Patrick Joseph Doherty (31), Bernard McGuigan (41), Hugh Pious Gilmour (17), Kevin McElhinney (17), Michael G. -

The Freedom of the City, Or How Reality Contaminates Art

31/12/2014 The Freedom Of The City, or How Reality Contaminates Art Find powered by FreeFind News home Home > Conferences > ESSE 2012 > S77: Abstracts > The Freedom Of The City, or How Reality Contaminates Art contact joining ASLS ShaSrheaSrheaSrheare 0 More 1 publications books The Freedom Of The City, or How Reality periodicals Contaminates Art Find your local booksellers, on the audio CDs high street or online, with the María Gaviña Costero Booksellers’ Association (UK and Ireland). conferences The Northern Irish playwright Brian Friel (Omagh, 1929) wrote his first play in 1958 and his last play, to date, in 2008. That makes five decades schools material dedicated to the stage, with no less than thirty plays. Occidental society has undergone deep changes in these fifty years, more dramatically so in Northern Ireland. The different tendencies in drama, the political and social articles & essays circumstances in both nations – the Republic and the North – the evolution in the way of understanding family and religion, the different about ASLS attitudes towards gender roles, have marked Friel’s oeuvre and signalled him as a spokesman for a community that was a British colony at the beginning of the 20th century and finds itself negotiating the foundations honorary fellows that will definitely end up with the conflict derived from its de-colonization at the beginning of the 21st century. In Friel’s career we find several plays CALL FOR PAPERS that act as landmarks. As we will see, The Freedom of the City (1973) is order form EMPIRES AND REVOLUTIONS: Friel’s first mature attempt to bring together his artistic vein and his R. -

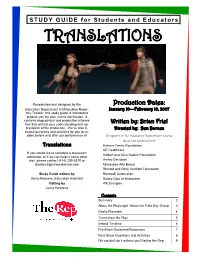

Translations

STUDY GUIDE for Students and Educators TRANSLATIONS Researched and designed by the Production Dates: Education Department at Milwaukee Reper- January 10—February 10, 2007 tory Theater, this study guide is intended to prepare you for your visit to the theater. It contains biographical and production informa- tion that will aid your understanding and ap- Written by: Brian Friel preciation of the production. We’ve also in- Directed by: Ben Barnes cluded questions and activities for you to ex- plore before and after our performance of Programs in the Education Department receive generous funding from: Translations Einhorn Family Foundation GE Healthcare If you would like to schedule a classroom Halbert and Alice Kadish Foundation workshop, or if we can help in some other way, please contact (414) 290-5370 or Harley Davidson [email protected] Milwaukee Arts Board Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation Study Guide written by Rockwell Automation Dena Roncone, Education Assistant Rotary Club of Milwaukee Editing by WE Energies Jenny Kostreva Contents Summary 2 About the Playwright /About the Field Day Group 3 Gaelic Proverbs 4 Terms from the Play 5 Ireland Timeline 6 Pre-Show Questions/Resources 7 Post-Show Questions and Activities 8 We couldn’t do it without you/Visiting the Rep 9 1 Summary Translations takes place in a hedge-school in the Book. Yolland keeps getting distracted from his work townland of Baile Beag/Ballybeg, an Irish-speaking and discusses the beauty of the country, the language community in County Donegal. and the people. Yolland wants to learn Gaelic and con- templates living in Ireland. -

A Critical Study of Brian Friel's Nationalism: Friel Between Politics

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5766 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0484 (Online) Vol.10, No.4, 2020 A Critical Study of Brian Friel’s Nationalism: Friel Between Politics and Nationalism Dr Amal Riyadh Kitishat Al Balqa Applied University- Ajloun University College, Dept. of English Language. Postal address: Jordan, Ajloun. Al Balqa Applied University. Ajloun University College, P.O box (1) Postal code 26816 Abstract Taking the Historical background into consideration, the study will shed light on Friel's political and national dogmas. The study addresses large and important issue concerning Friel’s role as the national dramatist of Ireland. The study examines the relationship between Friel's drama and his political stance and by extension the larger issues of literature and colonialism and literature and history. The study aims at proving that Friel is a nationalist but not a politician; in other words, the study argues that Friel’s philosophy of the Field Day theatre is seen within a cultural perspective. Friel’s plays are not only related to the political situation in Ireland, but they are also employed to shed light on the Irish cultural context. Thus, Friel’s establishment of the Field Day Theatre comes as a confirmation of Friel’s cultural insights which though presented Irish life. Still it did not follow a direct historical or a political treatment of the themes of his plays, rather he focused on stressing the national identity of the Irish audience. The study proved that Friel’s works are nationalist in tendency within a cultural perspective. -

ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to Dancing at Lughnasa Heidi

ABSTRACT A Director’s Approach to Dancing at Lughnasa Heidi Breeden, M.F.A. Mentor: Marion Castleberry, Ph.D. This thesis details the production process for Baylor Theatre’s mainstage production of Dancing at Lughnasa by Brian Friel, directed by Heidi Breeden, in partial fulfillment of the Master of Fine Arts in Directing. Dancing at Lughnasa is a somewhat autobiographical memory play, featuring strong roles for women and requiring advanced acting skills. This thesis first investigates the life and works of Brian Friel, then offers a director’s analysis of the text, documents the director’s process for the production, and finally offers a reflection on the strengths and opportunities for improvement for the director’s future work. A Director's Approach to Dancing at Lughnasa by Heidi Breeden, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Theatre Arts Stan C. Denman, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee Marion D. Castleberry, Ph.D., Chairperson DeAnna M. Toten Beard, M.F.A., Ph.D. David J. Jortner, Ph.D. Richard R. Russell, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2017 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. Copyright © 2017 by Heidi Breeden All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................... -

"We Endure Around Truths Immemorially Posited”: A

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Undergraduate Research Awards Student Scholarship and Creative Works 2011 "We Endure Around Truths Immemorially Posited”: a Dramaturgical Research Analysis on Brian Friel’s Linguistic-Historical Drama “Translations” Meredith Levy Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Levy, Meredith, ""We Endure Around Truths Immemorially Posited”: a Dramaturgical Research Analysis on Brian Friel’s Linguistic- Historical Drama “Translations”" (2011). Undergraduate Research Awards. 7. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Works at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Awards by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 2011 Wyndham Robertson Library Undergraduate Research Awards Essay by Meredith Levy “ “We Endure Around Truths Immemorially Posited”: A Dramaturgical Research Analysis on Brian Friel’s linguistic-historical drama Translations” My purpose in compiling a dramaturgical research report on Brian Friel’s linguistic-historical drama TRANSLATIONS was to construct a comprehensible body of writing that would aid a hypothetical director in her/his process of staging TRANSLATIONS. When choosing what about/around the play I wanted to research, I adopted the assumption that my audience had no prior knowledge of Northern Irish politics and culture. To start, I mapped out what general areas needed to be explored: Friel’s life and writings, the historical context of the setting (1833), the historical context of the play’s genesis (1980), production history, and critical analysis of the play’s themes, characters, and production elements. -

Redalyc.BRIAN FRIEL: the MASTER PLAYWRIGHT

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Pelletier, Martine BRIAN FRIEL: THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHT Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 135-156 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Brian Friel: the master playwright 135 BRIAN FRIEL: THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHT Martine Pelletier University of Tours, France Abstract: Brian Friel has long been recognized as Ireland’s leading playwright. His work for the theatre spans almost fifty years and his reputation has expanded well beyond Ireland. In January 2009 Friel turned eighty and only a few months before, his adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, opened at the Gate Theatre Dublin on 30th September 2008. This article will first provide a survey of Brian Friel’s remarkable career, trying to assess his overall contribution to Irish theatre, before looking at his various adaptations to finally focus on Hedda Gabler, its place and relevance in the author’s canon. Keywordsds: Brian Friel, Irish Theatre, Hedda Gabler, Adaptation, Ireland. Brian Friel has long been recognized as the leading playwright in contemporary Ireland. His work for the theatre spans almost fifty years and his reputation has expanded beyond Ireland and outside the English-speaking world, where several of his plays are regularly produced, studied and enjoyed by a wide range of audiences and critics. -

TWO GREAT POLITICAL PLAYS from IRELAND Ilha Do Desterro: a Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, Núm

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Kosok, Heinz DOOMED VOLUNTEERS: TWO GREAT POLITICAL PLAYS FROM IRELAND Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 77-98 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Doomed Volunteers: Two Great Political... 77 DOOMED VOLUNTEERS: TWO GREAT POLITICAL PLAYS FROM IRELAND Heinz Kosok University of Wuppertal Abstract: Seamus Byrne’s Design for a Headstone (1950) and Brian Friel’s Volunteers (1975) are some of the most controversial plays in the canon of Irish drama, exceptional in their explicit political implications. Loosely based on the role of the IRA in the Republic, they achieve a high degree of universality in their discussion of such provocative issues as political radicalism, internment, hunger strike, the role of the Church in society, passive resistance vs. active rebellion, justice vs. humanity, and loyalty vs. betrayal. In their tragic endings, both plays reveal a deep pessimism on the part of their authors. Keywordsds: Byrne, Friel, Political Drama, IRA, Tragedy. Frank O’Connor, in The Backward Look, has claimed that all Irish literature is characterised by what he calls a “political note”, and he insists: “I know no other literature so closely linked to the immediate reality of politics” (121).