A Border Between France and Spain Or Between Iparralde and Hegoalde? Contested Imaginations of a Basque Borderland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Hondarribia Walking Tour Way of St

countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Spain: San Sebastian, Bilbao & Basque Country Flight + Tour Combo Itinerary Free-roaming horses wander the green pastures atop Mount Jaizkibel, where your walk brings panoramic views extending clear across Spain into southern France—from the Bay of Biscay to the Pyrenees. You’re on a walking tour in the Basque Country, a unique corner of Europe with its own ancient language and culture. You’ve just begun exploring this fascinating region—from Bilbao’s cutting-edge architecture to Hendaye’s beaches to the mountainous interior. Your week ahead also promises tasty glimpses of local culinary culture: a Basque cooking class, a festive dinner at a traditional gastronomic club, a homemade feast in a hillside farmhouse…. Speaking of food, isn’t it about time to begin your scenic seaward descent through the vineyards for lunch and wine tasting? On egin! (Bon appetit!) Highlights Join a private gastronomic club, or txoko, for an exclusive dinner as the members share their love of Basque cuisine. Live like royalty in a setting so beautiful it earned the honor of hosting Louis XIV and Maria Theresa’s wedding in St. Jean de Luz. Experience the vibrant nightlife in a Basque wine bar. Stroll the seaside paths that Spanish aristocracy once wandered in San Sebastián. Tour the world-famous Guggenheim Museum – one of the largest museums on Earth and an architectural phenomenon. Satisfy your cravings in a region with more Michelin-star rated restaurants than Paris. Rest your mind and body in a restored 17th-century palace, or jauregia. 1 / 10 countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Participate in a cooking demonstration of traditional Basque cuisine. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface......................................................................................... -

March) 2011 UDALEKU 2011: Join the Team!

Gure Euskal Etxea Newsletter website : www.SFBCC.us . Volume 30 Issue 1 `` Martxa (March) 2011 UDALEKU 2011: Join the team! Upcoming Events Every four years the San Francisco Basque Cultural Center hosts the NABO • Mar 6-Women’s Club Meeting 10:00am Udaleku—a summer camp for Basque children from the ages of 10 - 15 years old. • Mar 14-Marin-Sonoma Basque Club Mus Tournament This camp has been one of NABO's most successful programs, teaching children • Mar 27-Mobile Blood Drive 9am—2pm about Basque culture, and most importantly making friends and connections • Mar 27-Birthday Celebration 1935 through 1945 • Apr 1- BEO Basque Film Series VACAS 7:30pm** throughout the United States. • Apr 2– BEO-NABO Lecture Series 10am and 1pm** Udaleku comes back to San Francisco from June 20th - July 3rd, 2011. • Apr 16-Korrika 2011 at Speedway Meadows • Apr 17-Palm Sunday Lunch For Udaleku to be successful, we need your help. We are looking for volun- • May 12-Mother’s Day Lunch teers to help with coordinating, housing, and transportation. If you are interested, • May 20-BEO Basque Film Series OGRO 7:30pm • Jun 5-Basque Club Picnic in Petaluma please contact Valerie Arrechea at 415-859-1154 ( [email protected] ) or Lisa • Jun 12-BCC General Meeting and Elections Etchepare ( [email protected] ) • Jun 20-Jul 3– NABO Udaleku All volunteers are welcome, from those who can house a few children, to those Gazteak Basque Dance Saturdays 1:00-3:00 pm who can help serve during dinner. Euskara Classes Thursday Evenings at 7:30 pm An Hour of your day on NABO Lecture Series March 27 can save a life! Board of Directors The NABO Lecture series will be making a stop There is an ongoing need for blood donors President at the Basque Cultural Center on Saturday, Philippe Acheritogaray Please help the BCC support the Blood Centers of the April 2nd , with lectures by Basque Studies Vice Presidents Tony Espinal Pacific in the ongoing need for blood donations. -

San Sebastián-Donostia Maribel’S Guide to San Sebastián ©

San Sebastián-Donostia Maribel’s Guide to San Sebastián © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ September 2019 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 3 • Vinoteca Bernardina Exploring Donostia On Your Own - Page 5 • Damadá Gastroteka Guided City Tours - Page 9 Dining in San Sebastián-Donostia The Michelin Stars - Page 34 Private City Tours - Page 10 • Akelaŕe Cooking Classes and Schools - Page 11 • Mugaritz San Sebastián’s Beaches - Page 12 • Restaurant Martín Berasategui • Restaurant Arzak Donostia’s Markets - Page 14 • Kokotxa Sociedad Gastronómica - Page 15 • Mirador de Ulia Performing Arts - Page 16 • Amelia • Zuberoa My Shopping Guide - Page 17 • Restaurant Alameda Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” - Page 18 Creative and Contemporary Cuisine - Page 35 Our Favorite Stops In The Parte Vieja - Page 20 • Biarritz Bar and Restaurant • Restaurante Ganbara • Casa Urola • Casa Vergara • Bodegón Alejandro • A Fuego Negro • Bokado Mikel Santamaria • Gandarias • Eme Be Garrote • La Cuchara de San Telmo • Agorregi • Bar La Cepa • Rekondo • La Viña • Galerna Jan Edan • Bar Tamboril • Zelai Txiki • Bar Txepetxa • La Muralla • Zeruko Taberna • La Fábrica • La Jarana Taberna • Urepel • Bar Néstor • Xarma Cook & Culture • Borda Berri • Juanito Kojua • Casa Urola • Astelena 1997 Our Favorites Stops In Gros - Page 25 • Aldanondo La Rampa • Ni Neu • • Gatxupa Gastronomic Splurges Outside The City - Page 41 • Topa Sukaldería • Restaurant Fagollaga • Ramuntxo Berri • Asador Bedua • Bodega Donostiarra -

Convention Between France and Spain on the Delimitation

page 1| Delimitation Treaties Infobase | accessed on 13/03/2003 Convention between France and Spain on the delimitation of the territorial sea and the contiguous zone in the Bay of Biscay (Golfe de Gascogne/Golfo de Vizcaya) (with map), 29 January 1974(1) The President of the French Republic, The Head of the Spanish State, Desiring to delimit the French territorial sea and the Spanish territorial sea and contiguous zone, Bearing in mind the Convention of 14 July 1959 between France and Spain relating to fishing in the Bidassoa (Bidasoa) River and in Figuier (Higuer) Bay, Have resolved to conclude a Convention and for that purpose have appointed as their plenipotentiaries: The President of the French Republic: Mr. Jean-Pierre Cabouat, Minister Plenipotentiary; The Head of the Spanish State: Mr. Antonio Poch, Minister Plenipotentiary, who, having exchanged their full powers, found in good and due form, have agreed as follows: Article 1. This Convention shall apply in the Bay of Biscay north of Figuier (Higuer) Bay to a distance of 12 miles, measured from the French and Spanish baselines. Article 2. 1. In the area specified in article 1, the line delimiting the French territorial sea with respect to both the Spanish territorial sea and contiguous zone shall be composed of two geodetic lines defined as follows: (a) The first geodetic line follows the meridian, passing through point M at the mid-point of a line AD joining Cape Higuer (Erdico point) in Spain to SainteAnne or Tombeau point in France. This line extends from point M northwards to point P situated at a distance of six miles from point M. -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

The Romance of War, Or, the Highlanders in Spain: the Peninsular War and the British Novel

THE ROMANCE OF WAR, OR, THE HIGHLANDERS IN SPAIN: THE PENINSULAR WAR AND THE BRITISH NOVEL Brian J. DENDLE University of Kentucky Wellington's Peninsular campaigns aroused considerable interest among British historians and reading public throughout the nineteenth century and even into the present decade of the twentieth century. The most recent historian of the war, David Gates, in The Spanish Ulcer (1986), counts some three hundred published personal memoirs and diaries, mainly British, in his bibliography. The war in the Iberian Península was savagely fought by British, Spanish, Portuguese, and French troops, as well as by Spanish and Portuguese irregular forces (the guerrilleros). When not fighting, British and French troops at times fraternized and observed a chivalrous respect for each other. The sufferings caused by the war were immense, including the looting and devastation of French-occupied Spain, the starvation of many Spaniards and Portuguese, and a very high casualty rate among the troops involved. Indeed, British soldiers frequently collapsed and died under the excessive loads they were compelled to carry'.For the British, the campaign represented the success of a small and previoüsly despised army, under the remarkable leadership of Wellington, over Napoleon's veterans. Spanish historians, on the other hand, stress the Spanish contribution to the successful outcome of the war2. 1. For a vivid first-hand account of the savage discipline enforced in Wellington's army and the atrocious sufferings of British soldiers, especially during the retíeat to Vigo, see Christopher Hibbert, cd., Recollections ofRifleman Harris, Hamden, Connecticut, Archon Books, 1970. 2. The American literary scholar Roger L. -

Basque Soccer Madness a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

University of Nevada, Reno Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Basque Studies (Anthropology) by Mariann Vaczi Dr. Joseba Zulaika/Dissertation Advisor May, 2013 Copyright by Mariann Vaczi All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Mariann Vaczi entitled Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joseba Zulaika, Advisor Sandra Ott, Committee Member Pello Salaburu, Committee Member Robert Winzeler, Committee Member Eleanor Nevins, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2013 i Abstract A centenarian Basque soccer club, Athletic Club (Bilbao) is the ethnographic locus of this dissertation. From a center of the Industrial Revolution, a major European port of capitalism and the birthplace of Basque nationalism and political violence, Bilbao turned into a post-Fordist paradigm of globalization and gentrification. Beyond traditional axes of identification that create social divisions, what unites Basques in Bizkaia province is a soccer team with a philosophy unique in the world of professional sports: Athletic only recruits local Basque players. Playing local becomes an important source of subjectivization and collective identity in one of the best soccer leagues (Spanish) of the most globalized game of the world. This dissertation takes soccer for a cultural performance that reveals relevant anthropological and sociological information about Bilbao, the province of Bizkaia, and the Basques. Early in the twentieth century, soccer was established as the hegemonic sports culture in Spain and in the Basque Country; it has become a multi- billion business, and it serves as a powerful political apparatus and symbolic capital. -

Bidasoa Greenway (Navarra

Bidasoa Greenway The Bidasoa is a short river which runs through Navarre and the Basque Country and forms the border between Spain and France on its way to Irun. It is best known precisely for its role as an international border and because of the railway which follows its course. The Bidasoa Greenway recovers much of the route of the Tren Txikito (Little Train) which used to run from Elizondo to Irun, and provides an unforgettable journey some 39 km long which takes us through some beautiful villages of Guipúzcoa and Navarre on the banks of the river Bidasoa. TECHNICAL DATA CONDITIONED GREENWAY On the banks of Bidasoa and next to the Lordship of Bértiz: dense forests and traditional villages Basques. LOCATION BetweenLegasa Bertizana (Navarra) and Behobia. Irún (Gipuzkoa) NAVARRA-PAÍS VASCO Length: 39 km Users: * *Legasa-Sunbilla (9,3 Km): suitable Sunbilla-Lesaka (13 Km): suitable with difficulties (potholes and mud) Lesaka-Bera/Vera de Bidasoa (3 Km): suitable Bera/Vera de Bidasoa-Behobia (13,7 km): suitable Type of surface: Legasa-Doneztebe/Santesteban(2,3 km) : mixed earth and concrete Doneztebe/Santesteban-Sunbilla(7 Km): concrete Sunbilla-Lesaka (13 Km): compacted earth Lesaka-Bera/Vera de Bidasoa (3 Km): tarmac Bera/Vera de Bidasoa-Endarlatza (6 Km): compacted earth Endarlatza-Behobia (7,7 km): Compacted gravel to some asphalt stages in the environment and Behobia Endarlatza Natural landscape: Atlantic forest and river banks. Prados. Natural Park of the Lordship of Bertiz. Pyrenees and natural park Aiako Harria (Peñas de Aya) Cultural heritage: Navarra: Urban ensembles of all peoples of the area. -

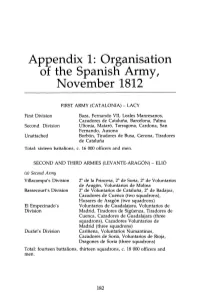

Appendix 1: Organisation of the Spanisn Army, November 1812

Appendix 1: Organisation of the Spanisn Army, November 1812 FIRST ARMY (CATALONlA) - LACY First Division Baza, Fernando VII, Leales Manresanos, Cazadores de Catalufla, Barcelona, Palma Second Division Ultonia, Matar6, Tarragona, Cardona, San Fernando, Ausona Unattached Borb6n, Tiradores de Busa, Gerona, Tiradores de Catalufla Total: sixteen battalions, c. 16 000 officers and men. SECOND AND THIRD ARMIES (LEV ANTE-ARAGON) - EUO (a) Second Army Villacampa' s Division 2° de la Princesa, 2° de Soria, 2° de Voluntarios de Arag6n, Voluntarios de Molina Bassecourt' s Division 2° de Voluntarios de Catalufla, 2° de Badajoz, Cazadores de Cuenca (two squadrons), Husares de Arag6n (two squadrons) EI Empecinado' s Voluntarios de Guadalajara, Voluntarios de Division Madrid, Tiradores de Sigüenza, Tiradores de Cuenca, Cazadores de Guadalajara (three squadrons), Cazadores Voluntarios de Madrid (three squadrons) Duran' s Division Cariflena, Voluntarios Numantinos, Cazadores de Soria, Voluntarios de Rioja, Dragones de Soria (three squadrons) Total: fourteen battalions, thirteen squadrons, c. 18 000 officers and men. 182 Appendix 1 183 (h) Third Army Vanguard - Freyre 1er de Voluntarios de la Corona, 1er de Guadix, Velez Malaga, Carabinieros Reales (one squadron), 1er Provisional de Linea (three squadrons), 2° Provisional de Linea (three squadrons), 1er Provisional de Dragones, (three squadrons), 2° Provisional de Dragones (three squadrons), 1er Provisional de Husares (two squadrons) Roche' s Division Voluntarios de Alicante, Canarias, Chinchilla, Cazadores de Valencia, Husares de Fernando VII (three squadrons) Montijo's Brigade 2° de Guardias Walonas, 1er de Badajoz, Cuenca Michelena' s Brigade 1er de Voluntarios de Arag6n, Tiradores de Cadiz, 2° de Mallorca Mijares' Brigade 1"' de Burgos, Alcazar de San Juan, BaHen, Lorca, Voluntarios de Jaen U na ttachedl garrisons Almansa, America, Alpujarras, Almeria, Cazadores de Jaen (one squadron), Cazadores de la Mancha (two squadrons) Total: twenty-two battalions, twenty-one squadrons, c. -

Wellington's Two-Front War: the Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Wellington's Two-Front War: The Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L. Moon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WELLINGTON’S TWO-FRONT WAR: THE PENINSULAR CAMPAIGNS, 1808 - 1814 By JOSHUA L. MOON A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Joshua L. Moon defended on 7 April 2005. __________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ______________________________ Edward Wynot Committee Member ______________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named Committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS No one can write a dissertation alone and I would like to thank a great many people who have made this possible. Foremost, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Donald D. Horward. Not only has he tirelessly directed my studies, but also throughout this process he has inculcated a love for Napoleonic History in me that will last a lifetime. A consummate scholar and teacher, his presence dominates the field. I am immensely proud to have his name on this work and I owe an immeasurable amount of gratitude to him and the Institute of Napoleon and French Revolution at Florida State University.