Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

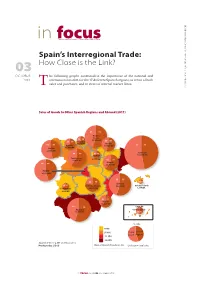

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic

water Review Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic Valentina S. Artamonova 1, Ivan N. Bolotov 2,3,4, Maxim V. Vinarski 4 and Alexander A. Makhrov 1,4,* 1 A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics, Northern Arctic Federal University, 163002 Arkhangelsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 163000 Arkhangelsk, Russia 4 Laboratory of Macroecology & Biogeography of Invertebrates, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of zoogeographic, paleogeographic, and molecular data has shown that the ancestors of many fresh- and brackish-water cold-tolerant hydrobionts of the Mediterranean region and the Danube River basin likely originated in East Asia or Central Asia. The fish genera Gasterosteus, Hucho, Oxynoemacheilus, Salmo, and Schizothorax are examples of these groups among vertebrates, and the genera Magnibursatus (Trematoda), Margaritifera, Potomida, Microcondylaea, Leguminaia, Unio (Mollusca), and Phagocata (Planaria), among invertebrates. There is reason to believe that their ancestors spread to Europe through the Paratethys (or the proto-Paratethys basin that preceded it), where intense speciation took place and new genera of aquatic organisms arose. Some of the forms that originated in the Paratethys colonized the Mediterranean, and overwhelming data indicate that Citation: Artamonova, V.S.; Bolotov, representatives of the genera Salmo, Caspiomyzon, and Ecrobia migrated during the Miocene from I.N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Makhrov, A.A. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Barakaldo – España

EUROPAN 6 – BARAKALDO – ESPAÑA Location: Barakaldo, Desembocadura del río Galindo Population: 100,000 inhab. Study area: 29 ha CONURBATION SITE Barakaldo, second most populated town in Biscay, is situated between the On an area totalling 500 000 m2, previously occupied by an iron and steel left bank of the Nervion estuary, just downstream of Bilbao. Of Barakaldo’s works, BR2000 is developing an ambitious urban, social, and economic rege- 100 000 inhabitants, 70% live in the centre. Historically it is an important in- neration project. The site is at the centre of the area, in the confluence of the dustrial centre (chemicals, iron and steel). It is the disappearance of one the Nervion and Galindo rivers, and adjoins a former EUROPAN 5 site; a location biggest of these companies, Altos Hornos of Bilbao, that has opened up the with the potential to give Barakaldo and the estuary on which it stands, a new possibility for urban regeneration of large tracts of land. image. FUNCTIONAL ISSUES The main issue is, with the help of a complete urban project to be built in the Galindo river sector, the extension of the town centre on the riverfront formed by the Nervion and Galindo. The proposed site constitutes the cornerstone. EUROPAN 6 – BARAKALDO – ESPAÑA SOCIAL ISSUES PROGRAMME Although the project for the site chiefly concerns a residential scheme, it is The programme calls for management through to completion of a scheme nonetheless necessary to place it in a much wider context, envisaging busi- that provides 19 000 m2 of housing. There are no preliminary conditions in ness activity, transport and other networks, public spaces, pedestrian spaces, terms of construction typology, implantation, or outline. -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Primera Cita De Reproducción De Cigüeñuela Común Himantopus

Munibe (Ciencias Naturales-Natur Zientziak) • Nº 60 (2012) • pp. 253-256 • DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIÁN • ISSN 0214-7688 Primera cita de reproducción de cigüeñuela común Himantopus himantopus L., 1758 en Urdaibai (Bizkaia) First breeding record of common stilt Himantopus himantopus L., 1758 at Urdaibai (Bizkaia) JUAN ARIZAGA 1*, AINARA AZKONA 1, XARLES CEPEDA 1, JON MAGUREGI 1, EDORTA UNAMUNO 1, JOSÉ M. UNAMUNO 1 RESUMEN La colonización del Cantábrico por la cigüeñuela común Himantopus himan- topus L., 1758 es un fenómeno reciente (se cita por primera vez en 2009 en Asturias y Cantabria). En 2012, y por primera vez para Urdaibai y la costa vasca, se constata la reproducción de cigüeñuela en la laguna de Orueta, en el municipio de Gautegiz-Arteaga (Bizkaia). En particular, una pareja fue capaz de sacar adelante 3 pollos. • PALABRAS CLAVE: Cantábrico, Gautegiz-Arteaga, humedales, limícolas, marismas costeras. ABSTRACT The common stilt Himantopus himantopus L., 1758 has colonized the coast along northern Spain recently (it bred for the first time in 2009 in Asturias and Cantabria). In 2012, and for the first time at Urdaibai and the Basque coast, one pair bred successfully in the Orueta lagoon, within the municipality of Gautegiz-Arteaga (Bizkaia). This pair was able to rear 3 chicks. • KEY WORDS: Bay of Biscay, coastal marshes, Gautegiz-Arteaga, waders, wetlands. LABURPENA Zankaluzeak Himantopus himantopus L., 1758 Kantauriar kosta kolonizatzea gertakari berria da (lehen zita 2009. urtekoa da, Asturias eta Kantabrian). 2012 urtean lehen aldiz, Urdaibain, eta honenbestez Euskal kostaldean, zankaluze- aren ugalketa egiaztatu da. Zankaluzeak Gautegiz-Arteaga herrian (Bizkaia) 1 Urdaibai Bird Center/Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi. -

Temperature Variability in the Bay of Biscay During the Past 40 Years, from an in Situ Analysis and a 3D Global Simulation

ARTICLE IN PRESS Continental Shelf Research 29 (2009) 1070–1087 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Continental Shelf Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/csr Temperature variability in the Bay of Biscay during the past 40 years, from an in situ analysis and a 3D global simulation S. Michel a,Ã, A.-M. Treguier b, F. Vandermeirsch a a Dynamiques de l’Environnement Coˆtier/Physique Hydrodynamique et Se´dimentaire, IFREMER, BP 70, 29280 Plouzane´, France b Laboratoire de Physique des Oce´ans, CNRS-IFREMER-IRD-UBO, BP 70, 29280 Plouzane´, France article info abstract Article history: A global in situ analysis and a global ocean simulation are used jointly to study interannual to decadal Received 21 June 2008 variability of temperature in the Bay of Biscay, from 1965 to 2003. A strong cooling is obtained at all Received in revised form depths until the mid-1970’s, followed by a sustained warming over 30 years. Strong interannual 21 November 2008 fluctuations are superimposed on this slow evolution. The fluctuations are intensified at the surface and Accepted 27 November 2008 are weakest at 500 m. A good agreement is found between the observed and simulated temperatures, Available online 6 February 2009 in terms of mean values, interannual variability and time correlations. Only the decadal trend is Keywords: significantly underestimated in the simulation. A comparison to satellite sea surface temperature (SST) Bay of Biscay data over the last 20 years is also presented. The first mode of interannual variability exhibits a quasi- Interannual temperature variability uniform structure and is related to the inverse winter North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index. -

THE DEVELOPMENT of MESOZOIC SEDIMENTARY IBASINS AROUND the MARGINS of the NORTH ATLANTIC and THEIR HYDROCARBON POTENTIAL D.G. Masson and P.R

INTERNAL DOCUMENT IIL THE DEVELOPMENT OF MESOZOIC SEDIMENTARY IBASINS AROUND THE MARGINS OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC AND THEIR HYDROCARBON POTENTIAL D.G. Masson and P.R. Miles Internal Document No. 195 December 1983 [This document should not be cited in a published bibliography, and is supplied for the use of the recipient only]. iimsTit\jte of \ OCEANOGRAPHIC SCIENCES % INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHIC SCIENCES Wormley, Godalming, Surrey GU8 5UB (042-879-4141) (Director: Dr. A. S. Laughton, FRS) Bidston Observatory, Crossway, Birkenhead, Taunton, Mersey side L43 7RA Somerset TA1 2DW (051-653-8633) (0823-86211) (Assistant Director: Dr. D. E. Cartwright) (Assistant Director: M.J. Tucker) THE DEVELOPMENT OF MESOZOIC SEDIMENTARY BASINS AROUND THE MARGINS OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC AND THEIR HYDROCARBON POTENTIAL D.G. Masson and P.R. Miles Internal Document No. 195 December 1983 Work carried out under contract to the Department of Energy This document should not be cited in a published bibliography except as 'personal communication', and is supplied for the use of the recipient only. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Brook Road, Wormley, Surrey GU8 SUB ABSTRACT The distribution of Mesozoic basins around the margins of the North Atlantic has been summarised, and is discussed in terms of a new earliest Cretaceous palaeogeographic reconstruction for the North Atlantic area. The Late Triassic-Early Jurassic rift basins of Iberia, offshore eastern Canada and the continental shelf of western Europe are seen to be the fragments of a formerly coherent NE trending rift system which probably formed as a result of tensional stress between Europe, Africa and North America. The separation of Europe, North America and Iberia was preceded by a Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous rifting phase which is clearly distinct from the earlier Mesozoic rifting episode and was little influenced by it. -

Suspended Sediment Delivery from Small Catchments to the Bay of Biscay. What Are the Controlling Factors ?

Open Archive TOULOUSE Archive Ouverte (OATAO) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author-deposited version published in : http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID : 16604 To link to this article : DOI : 10.1002/esp.3957 URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/esp.3957 To cite this version : Zabaleta, Ane and Antiguedad, Inaki and Barrio, Irantzu and Probst, Jean-Luc Suspended sediment delivery from small catchments to the Bay of Biscay. What are the controlling factors ? (2016) Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, vol.41, n°13, pp. 1813-2004. ISSN 1096-9837 Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository administrator: [email protected] Suspended sediment delivery from small catchments to the Bay of Biscay. What are the controlling factors? Ane Zabaleta,1* liiaki Antiguedad,1 lrantzu Barrio2 and Jean-Luc Probst3 1 Hydrology and Environment Group, Science and Technology Faculty, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Leioa, Basque Country, Spain 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Statistics and Operations Research, Science and Technology Faculty, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Leioa, Basque Country, Spain 3 EcoLab, University of Toulouse, CNRS, INPT, UPS, Toulouse, France *Correspondence to: Ane Zabaleta, Hydrology and Environment Group, Science and Technology Faculty, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, 48940 Leioa, Basque Country, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The transport and yield of suspended sediment (SS) in catchments all over the world have long been tapies of great interest. -

Hondarribia Walking Tour Way of St

countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Spain: San Sebastian, Bilbao & Basque Country Flight + Tour Combo Itinerary Free-roaming horses wander the green pastures atop Mount Jaizkibel, where your walk brings panoramic views extending clear across Spain into southern France—from the Bay of Biscay to the Pyrenees. You’re on a walking tour in the Basque Country, a unique corner of Europe with its own ancient language and culture. You’ve just begun exploring this fascinating region—from Bilbao’s cutting-edge architecture to Hendaye’s beaches to the mountainous interior. Your week ahead also promises tasty glimpses of local culinary culture: a Basque cooking class, a festive dinner at a traditional gastronomic club, a homemade feast in a hillside farmhouse…. Speaking of food, isn’t it about time to begin your scenic seaward descent through the vineyards for lunch and wine tasting? On egin! (Bon appetit!) Highlights Join a private gastronomic club, or txoko, for an exclusive dinner as the members share their love of Basque cuisine. Live like royalty in a setting so beautiful it earned the honor of hosting Louis XIV and Maria Theresa’s wedding in St. Jean de Luz. Experience the vibrant nightlife in a Basque wine bar. Stroll the seaside paths that Spanish aristocracy once wandered in San Sebastián. Tour the world-famous Guggenheim Museum – one of the largest museums on Earth and an architectural phenomenon. Satisfy your cravings in a region with more Michelin-star rated restaurants than Paris. Rest your mind and body in a restored 17th-century palace, or jauregia. 1 / 10 countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Participate in a cooking demonstration of traditional Basque cuisine. -

European Collection 2015

European Collection 2015 WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN & THE RIVIERAS EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN & GREEK ISLES NORTHERN EUROPE & BRITISH ISLES CONTINENTAL EUROPE CONTENTS 2 EXPERIENCE 96 TRANSOCEANIC VOYAGES The OlifeTM 104 gRAND VOYAGES 16 TASTE The Finest Cuisine at Sea 114 EXPLORE ASHORE Shore Excursion Collections & Land Tour Series 28 VALUE Best Value in Upscale Cruising 123 HOTEL PROGRAMS Pre- & Post-Cruise Hotel Programs 32 OcEANIA CLUB 126 SUITES & STATEROOMS 34 DESTINATION SPECIALISTS Culinary Discovery ToursTM & New Ports of Call 136 DECK PLANS 42 WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN 140 PROGRAMS & INFORMATION & THE RIVIERAS Travel Protection & Air Program Details 62 EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN 142 CRUISE CALENDAR & GREEK ISLES 144 EXPERIENCE OcEANIACRUISES.COM 74 NORTHERN EUROPE & BRITISH ISLES 145 GENERAL INFORMATION Oceania Club Terms & Conditions 90 CONTINENTAL EUROPE ON THE COVER Scottish kilts originate back to the 16th century and were traditionally worn as full length garments by Gaelic-speaking male Highlanders of northern Scotland POINTS OF DISTINCTION n FREE AIRFARE* on every voyage n Mid-size, elegant ships catering to just 684 or 1,250 guests n Finest cuisine at sea, served in a variety of distinctive open-seating Europe Collection restaurants, at no additional charge n Gourmet culinary program crafted 2015 by world-renowned Master Chef Jacques Pépin THE MAGIC OF THE OLD WORLD | When millenniums of history and great works n of art meet captivating cultures and generous smiles, you know you’ve arrived in Europe. Spectacular port-intensive itineraries featuring overnight visits and extended From Michelangelo’s David in Florence to Rembrandt’s masterpieces in Amsterdam, you evening port stays will be awed and inspired. Stand on the Acropolis in Athens or explore the gilded czar palaces in St. -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean.