Japanese Tea Ceremony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German Porcelain Figural Group

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German porcelain figural group, depicting a pianist and dancers, each dressed in classical $ 500 $ 700 attire with crinoline accents, marked with underglaze blue mark, 11.5"h x 16"w x 9"d 7001 Framed group of 32 Wedgwood jasperware medallions, each depicting British royalty, $ 300 $ 500 overall 17.5"h x 33"w 7002 (lot of 2) Continental polychrome decorated pill boxes, including a Meissen example, $ 300 $ 500 largest 1"h x 2.5"w 7003 (lot of 2) Meissen figural candlestick group 19th century, each depicted holding a child, one $ 1,200 $ 1,500 figure in the Bacchanalian taste, having a grape cluster wreath, each depicted in Classical attire, and rising on a Rococco style base with bird form reserves, underside with underglaze blue cross sword mark, 13,5"h 7004 Continental style gilt bronze footed compote, having a garland swag decorated frieze $ 600 $ 900 flanking the ebonized bowl, above the fish form gilt bronze standard, and rising on a circular marble base, 8.5"h x 8"w 7005 (lot of 8) French hand painted porcelain miniature portraits; each depicting French royalty $ 800 $ 1,200 including Napoleon, and numerous ladies, largest 4"h x 3"w Provenance: from the Holman Estate in Pacific Grove. The Holman family were early residents of the Monterey Peninsula and established Holman's Department Store in the center of Pacific Grove, thence by family descent 7006 French Grand Tour style silver gilt mythological figure, depicting Bacchus or Dionysus, $ 1,500 $ 2,000 modeled as standing on a mound of grapes and leaves holding -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

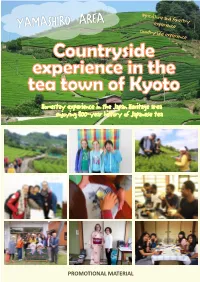

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 152 International Conference on Social science, Education and Humanities Research (ICSEHR 2017) Research on Chinese Tea Culture Teaching from the Perspective of International Education of Chinese Language Jie Bai Xi’an Peihua University, Humanities School Xi’an, China e-mail: [email protected] Abstract—This paper discusses the current situation of Chinese tea culture in teaching Chinese as a foreign language (TCFL) B. Chinese Tea Culture Teaching and points out that it is of great significance to introduce tea In May 2014, the Office of Chinese Language Council culture teaching under the background of global "Chinese International (Hanban) has promulgated the "International Popular", and finally puts forward some teaching strategies to Curriculum for Chinese Language Education (Revised bring inspiration for Chinese tea culture teaching. Edition)" (hereinafter referred to as the "Syllabus"), which refers to the "cultural awareness": "language has a rich Keywords-International Education of Chinese Language; cultural connotation. Teachers should gradually expand the Chinese Tea Culture;Teaching Strategies content and scope of culture and knowledge according to the students' age characteristics and cognitive ability, and help students to broaden their horizons so that learners can I. INTRODUCTION understand the status of Chinese culture in world With the rapid development of globalization, China's multiculturalism and its contribution to world culture. "[1] In language and culture has got more and more attention from addition, the "Syllabus" has also made a specific request on the world. More and more foreign students come to China to themes and tasks of cultural teaching, among which the learn Chinese and learn about Chinese culture and history, Chinese tea culture is one of the important themes. -

The Influence of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Tourist Experience on Authenticity, Tourist Satisfaction, and Acculturation

sustainability Article The Influence of Cross-Cultural Awareness and Tourist Experience on Authenticity, Tourist Satisfaction and Acculturation in World Cultural Heritage Sites of Korea Hao Zhang 1, Taeyoung Cho 2, Huanjiong Wang 1,* ID and Quansheng Ge 1,* 1 Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Airline Service Science, Joongbu University, 201 Daehak-ro, Chubu-myeon, Geumsan-gun, Chungnam 312-702, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.W.); [email protected] (Q.G.); Tel.: +86-10-6488-9831 (H.W.); +86-10-6488-9499 (Q.G.) Received: 12 January 2018; Accepted: 20 March 2018; Published: 23 March 2018 Abstract: This study aimed to identify the relationship among the following factors: cross-cultural awareness, tourist experience, authenticity, tourist satisfaction, and acculturation. It also sought to determine what role that tourist activities play in acculturation. Furthermore, this study looked to provide a feasibility plan for the effective management, protection, and sustainable development of World Cultural Heritage Sites. We chose Chinese in Korea (immigrants, workers, and international students) who visited the historic villages of Korea (Hahoe and Yangdong) as the research object, and used 430 questionnaires for analysis. The confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation model were used to verify proposed -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people. -

2014 YCAR Annual Report

Annual Report 2013.2014 Annual Report 2013.2014 1. Contact Information Dr Philip Kelly, Director. [email protected] Dr Janice Kim, Associate Director. [email protected] Alicia Filipowich, Coordinator. [email protected] York Centre for Asian Research (YCAR) 8th Floor, Kaneff Tower || 416.736.5821 | http://ycar.apps01.yorku.ca/ | [email protected] 2. Home Faculties for Active YCAR Faculty and Graduate Associates Education (1) Environmental Studies (6) Fine Arts (9) Health (2) Liberal Arts and Professional Studies (111) Glendon College (5) Osgoode Hall Law School (3) Schulich School of Business (3) 3. Chartering First Charter: May 2002; Last Renewal: March 2010 (for six years) 4. Mandate YCAR’s mandate is to foster and support research at York related to East, Southeast and South Asia, and Asian migrant communities in Canada and around the world. The Centre aims to provide: 1) Intellectual Exchange: facilitating interaction between Asia‐focused scholars at York, and between York researchers and a global community of Asia scholars; 2) Research Support: assisting in the development of research grants, and administering such projects; 3) Graduate Training: supporting graduate student training and research by creating an interdisciplinary intellectual hub, administering a graduate diploma program, and providing financial support for graduate research; 4) Knowledge Mobilization: providing a clear public point of access to York’s collective research expertise on Asia, and ensuring the wider dissemination of York research on Asia to academic and non‐academic -

Japanese Garden

満開 IN BLOOM A PUBLICATION FROM WATERFRONT BOTANICAL GARDENS SPRING 2021 A LETTER FROM OUR 理事長からの PRESIDENT メッセージ An opportunity was afforded to WBG and this region Japanese Gardens were often built with tall walls or when the stars aligned exactly two years ago! We found hedges so that when you entered the garden you were out we were receiving a donation of 24 bonsai trees, the whisked away into a place of peace and tranquility, away Graeser family stepped up with a $500,000 match grant from the worries of the world. A peaceful, meditative to get the Japanese Garden going, and internationally garden space can teach us much about ourselves and renowned traditional Japanese landscape designer, our world. Shiro Nakane, visited Louisville and agreed to design a two-acre, authentic Japanese Garden for us. With the building of this authentic Japanese Garden we will learn many 花鳥風月 From the beginning, this project has been about people, new things, both during the process “Kachou Fuugetsu” serendipity, our community, and unexpected alignments. and after it is completed. We will –Japanese Proverb Mr. Nakane first visited in September 2019, three weeks enjoy peaceful, quiet times in the before the opening of the Waterfront Botanical Gardens. garden, social times, moments of Literally translates to Flower, Bird, Wind, Moon. He could sense the excitement for what was happening learning and inspiration, and moments Meaning experience on this 23-acre site in Louisville, KY. He made his of deep emotion as we witness the the beauties of nature, commitment on the spot. impact of this beautiful place on our and in doing so, learn children and grandchildren who visit about yourself. -

Chinese Tea and Gongfu Tea Ceremony

Chinese Tea and GOngfu Tea CergmOny ShinzO ShiratOri Chinese tea has alwγ s reSOnated w⒒ h Ime since a yOung chⅡ d9⒛d me grOⅥ泛ng up with the temple,I wOuld always gO see the mOnks tO haⅤ e tea w⒒h them。 They wOuld brew up h tea ca11ed Pu Erh,which there盯e twO types;ε md the One they wOuld brew would a1wE∷ 3厂 s be th0 ripe kind。 This,I assume because the taste of ripened Pu Erh is qu⒒ e sknⅡar tO the taste Of Tibetan yak butter tea,which is piping hOt strong r1pened Pu Erh Or Hei Cha blended w⒒h churn。 d thick yak butter。 This tea is incredib1y salty and is nOt rny免 ⅤOr⒒ e9but⒒ surely dOes its jOb in the¨ 40degree Imountains in Tibet!-ALs early as65]BC,the Ancient Tea HOrse R`Oad was taking place between China and Tibet, Bengal md Myaασ泛r。 It was Ⅴital,as rnany Of the ancient I3uddhist traditions were brOught back from Tbet⒛ d My汕 1mar。 The tea was c盯r忆 d in sh::l∷ )eS of l[∶ bricks, and were traded Off fOr Tibetan hOrses tO be used ih different wεrs。 SO therefore9the Imain st。 ple for the Tibetans were Chin0se Pu Erh tea mi)λ1ed with y。 k butter to w泛、1rm the bO(i圩 ⒗ also g缸n immense ,厂 ,盯 mount of calories。 As grOv注 ng up as a Tibe⒈ Ⅱ1buddhis1I see the inter- cOnnection Of China and Tibet,and hOw One needed⒛ Other tO surⅤ iVe。 Pu¨ Erh tea,ImiXed with hot butter was the deal for the cOld,hOweⅤ er,the hOt刁reas in China alsO reⅡ ed On teas tO cOOl dOWn。 The Chinese uses tea in a ⅤI〕1If忆ty Of ways,and prOduces η 。ny types tO s证 t the needs Of different indiⅤiduals。 In⒛cient China9peOple wOuld use hot and cOld as a Imeasurement Of how w泛〕1Ifming -

Teaching Design of Chinese Tea Culture in English Class Based on ADDIE Model

International Education Studies; Vol. 12, No. 11; 2019 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Loss and Return of Chinese Culture in English Teaching: Teaching Design of Chinese Tea Culture in English Class Based on ADDIE Model Liu Yang1 & Yang Congzhou1 1 English Department, North China Electric Power University, Baoding, China Correspondence: Yang Congzhou, English Department, North China Electric Power University, 071000 Hebei, China. Received: July 8, 2019 Accepted: September 26, 2019 Online Published: October 28, 2019 doi:10.5539/ies.v12n11p187 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v12n11p187 Abstract Since the 21st century, China has put forward the “going out strategy of Chinese culture” which aims at realizing the awakening, reviving, integrating and spreading of Chinese culture. China emphasizes strengthening and improving the spreading of Chinese culture in order to enhance the soft power of national culture. China needs to cultivate intercultural communicative talents that can display Chinese culture to the world through an appropriate path with profound intercultural communication awareness and excellent intercultural communicative competence. Being representative of Chinese traditional culture, tea culture carries a long history of China. This paper takes the tea culture as an example for teaching design from the aspects of analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation based on the ADDIE model, aiming at optimizing the teaching design of Chinese culture into English teaching and cultivating students’ intercultural communicative ability. Keywords: ADDIE model, Chinese culture, teaching design, tea culture, intercultural communicative competence 1. Introduction Different eras require different talents and the target of education changes accordingly.