Towards a Holistic Approach in Peacekeeping Promoting Peace Through Training, Research and Policy Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in Mali

United Nations S/2016/1137 Security Council Distr.: General 30 December 2016 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2295 (2016), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2017 and requested me to report on a quarterly basis on its implementation, focusing on progress in the implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali and the efforts of MINUSMA to support it. II. Major political developments A. Implementation of the peace agreement 2. On 23 September, on the margins of the general debate of the seventy-first session of the General Assembly, I chaired, together with the President of Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, a ministerial meeting aimed at mitigating the tensions that had arisen among the parties to the peace agreement between July and September, giving fresh impetus to the peace process and soliciting enhanced international support. Following the opening session, the event was co-chaired by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, International Cooperation and African Integration of Mali, Abdoulaye Diop, and the Minister of State, Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Algeria, Ramtane Lamamra, together with the Under - Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations. In the Co-Chairs’ summary of the meeting, the parties were urged to fully and sincerely maintain their commitments under the agreement and encouraged to take specific steps to swiftly implement the agreement. Those efforts notwithstanding, progress in the implementation of the agreement remained slow. Amid renewed fighting between the Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) and the Platform coalition of armed groups, key provisions of the agreement, including the establishment of interim authorities and the launch of mixed patrols, were not put in place. -

1St Reported Case of Ebola in Mali: Strengthened Measures to Respond

Humanitarian Bulletin Mali September-October 2014 In this issue 1st case of Ebola virus disease P.1 Nutritional situation in Mali P.2 Food security survey P.3 HIGHLIGHTS Back to school 2014 - 2015 P.4 Information management trainings P.6 First confirmed case of SRP funding P.8 Ebola virus disease in Mali Clusters performance indicators P.8 Average prevalence of global acute malnutrition OCHA/D.Dembele reaches 13.3 percent National Food security 1st reported case of Ebola in Mali: survey : 24 per cent of households affected by strengthened measures to respond to the food insecurity epidemic KEY FIGURES On 23 October, the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene confirmed the first Ebola case in Mali; a two-year old girl who had travelled with her grandmother from Guinea # IDPs 99, 816 (Kissidougou) to Kayes city (Western Mali), transiting through Bamako. She had been (Commission on hospitalized in Kayes where she died on 24 October. Population Movements, 30 Sep.) In response to this Ebola outbreak, the Government, with the support of WHO and # Refugees in 14, 541 partners (NGOs and other UN agencies), have strengthened prevention measures while Mali (UNHCR 31 the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene and its partners immediately put under August) observation around forty people who had direct contact with the girl in Bamako and # Malian 143, 253 refugees ( UNHCR Kayes, while the tracking of other contacts continued. 30 Sep) Severely food 1,900,000 Experts from WHO regional office and headquarters, supported by the National Public insecure people Health Institute of Quebec (INSRPQ), USAID and CDC1, who were on a Ebola (Source : March 2014 Harmonized preparedness mission in Mali at the time, are supporting the response and the Framework) implementation of the National Ebola Emergency Plan. -

COUNTRY Food Security Update

MALI Food Security Outlook Update June 2013 Marketing conditions returning to normal in the north; decreased demand in the south KEY MESSAGES Figure 1 Current food security outcomes for June 2013 Cumulative rainfall totals for the period from May 1st through June 20th were generally normal to above- normal. Crop planting was slightly delayed by localized late June rains, particularly in structurally-deficit southern Kayes and western Koulikoro. Increased trade with normal supply areas in the south and accelerated humanitarian assistance have considerably improved staple food availability in northern markets, though import flows from Algeria are still limited. Exceptions include localized pastoral areas such as Ber (Timbuktu) and Anefif (Kidal), where persistent security problems continue to delay the recovery of market activities. Northern pastoral populations are still facing IPC Phase 3: Crisis levels of food insecurity. Source: FEWS NET Persistent weak demand in southern production markets This map shows relevant current acute food insecurity outcomes for triggered unusual price decreases between May and June, emergency decision-making. It does not necessary reflect chronic food ahead of the onset of the lean season in agropastoral insecurity. zones. The same trend is reported by rice-growing farmers in the Timbuktu region given the absence of Figure 2. Most likely estimated food security outcomes usual buyers and ongoing food assistance. for July through September 2013 The food security outlook for the southern part of the country is average to good and is starting to improve in the north with the various humanitarian programs underway, gradual economic recovery, and seasonal improvement in pastoral conditions. -

Soutenu Par Balla BAGAYOKO CIP Promotion Louis Pasteur (2017-2018)

Université Paris 1 École nationale d’administration Master Etudes européennes et relations internationales Spécialité Relations internationales et Actions à l’Étranger Parcours « Administration publique et Affaires internationales » L’intervention de l’Union européenne dans la crise malienne : une réaffirmation de la politique de sécurité et de défense commune Sous la direction de Madame Alix TOUBLANC, Maître de conférences en droit international public École de droit de la Sorbonne, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. Soutenu par Balla BAGAYOKO CIP Promotion Louis Pasteur (2017-2018). Juin 2018. Remerciements Je voudrais tout d’abord remercier le Gouvernement et le peuple français pour la bourse qui m’a permis de faire mes études à l’École nationale d’administration et à l’Université Paris 1. Je remercie la Direction générale, l’équipe pédagogique et tout l’encadrement de l’École nationale d’administration pour le dévouement. Je tiens à remercier Madame Alix TOUBLANC, pour avoir encadré ce mémoire. J’ai été extrêmement sensible à ses conseils avisés, ses qualités d’écoute et de compréhension. Mes remerciements vont également à mon binôme, Monsieur Franck SCHOUMACKER, pour sa relecture de ce travail. Mes pensées amicales à tous mes collègues du CIP, du CSPA et du CIO, de la promotion Louis Pasteur 2017-2018. Qu’ils trouvent dans ces lignes l’expression de ma reconnaissance pour leur soutien, jamais démenti, et leurs encouragements toujours soutenus. Enfin, je voudrais remercier toute ma famille pour l’affection et l’appui sans faille. -

Rebel Forces in Northern Mali

REBEL FORCES IN NORTHERN MALI Documented weapons, ammunition and related materiel April 2012-March 2013 Co-published online by Conflict Armament Research and the Small Arms Survey © Conflict Armament Research/Small Arms Survey, London/Geneva, 2013 First published in April 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of Conflict Armament Research and the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the secretary, Conflict Armament Research ([email protected]) or the secretary, Small Arms Survey ([email protected]). Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Reviewed by Alex Diehl and Nic Jenzen-Jones Cover image: © Joseph Penny, 2013 Above image: Design and layout by Julian Knott (www.julianknott.com) © Richard Valdmanis, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS About 4 3.7 M40 106 mm recoilless gun 11 Abbreviations and acronyms 5 4. Light Weapons Ammunition 12 Introduction 6 4.1 12.7 x 108 mm ammunition 12 4.2 14.5 x 115 mm ammunition 12 1. Small Arms 7 4.3 PG-7 rockets 13 1.1 Kalashnikov-pattern 7.62 x 39 mm assault 4.4 OG-82 and PG-82 rockets 13 rifles 7 4.5 82 mm mortar bombs 14 1.2 FN FAL-pattern 7.62 x 51 mm rifle 7 4.6 120 mm mortar bombs 14 1.3 G3-pattern 7.62 x 51 mm rifle 7 4.7 Unidentified nose fuzes 14 1.4 MAT-49 9 x 19 mm sub-machine gun 7 4.8 F1-pattern fragmentation grenades 15 1.5 RPD-pattern 7.62 x 39 mm light 4.9 NR-160 106 mm HEAT projectiles 15 machine gun 7 1.6 PK-pattern 7.62 x 54R mm general-purpose 5. -

A Peace of Timbuktu: Democratic Governance, Development And

UNIDIR/98/2 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva A Peace of Timbuktu Democratic Governance, Development and African Peacemaking by Robin-Edward Poulton and Ibrahim ag Youssouf UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.3 ISBN 92-9045-125-4 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research UNIDIR is an autonomous institution within the framework of the United Nations. It was established in 1980 by the General Assembly for the purpose of undertaking independent research on disarmament and related problems, particularly international security issues. The work of the Institute aims at: 1. Providing the international community with more diversified and complete data on problems relating to international security, the armaments race, and disarmament in all fields, particularly in the nuclear field, so as to facilitate progress, through negotiations, towards greater security for all States and towards the economic and social development of all peoples; 2. Promoting informed participation by all States in disarmament efforts; 3. Assisting ongoing negotiations in disarmament and continuing efforts to ensure greater international security at a progressively lower level of armaments, particularly nuclear armaments, by means of objective and factual studies and analyses; 4. -

Tuareg Nationalism and Cyclical Pattern of Rebellions

Tuareg Nationalism and Cyclical Pattern of Rebellions: How the past and present explain each other Oumar Ba Working Paper No. 007 Sahel Research Group Working Paper No. 007 Tuareg Nationalism and Cyclical Pattern of Rebellions: How the past and present explain each other Oumar Ba March 2014 The Sahel Research Group, of the University of Florida’s Center for African Studies, is a collaborative effort to understand the political, social, economic, and cultural dynamics of the countries which comprise the West African Sahel. It focuses primarily on the six Francophone countries of the region—Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad—but also on in developments in neighboring countries, to the north and south, whose dy- namics frequently intersect with those of the Sahel. The Sahel Research Group brings together faculty and gradu- ate students from various disciplines at the University of Florida, in collaboration with colleagues from the region. Abstract: This article stresses the importance of history in understanding the cyclical pattern of Tuareg rebellions in Mali. I argue that history and narratives of bravery, resistance, and struggle are important in the discursive practice of Tuareg nationalism. This discourse materializes in the episodic rebellions against the Malian state. The cyclical pattern of the Tuareg rebellions is caused by institutional shortcomings such as the failure of the Malian state to follow through with the clauses that ended the previous rebellions. But, more importantly, the previous rebellions serve as historical and cultural markers for subsequent rebellions, which creates a cycle of mutually retrospective reinforcement mechanisms. About the Author: Oumar Ba is a Ph. -

MINUSMA's 2021 in Uncertain Times

MINUSMA’s 2021 Mandate Renewal in uncertain times Arthur Boutellis Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2021 ISBN: 978-82-7002-350-9 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Cover photo: UNPhoto / MINUSMA Investigates Human Rights Violations in Bankass Area MINUSMA’s 2021 mandate renewal in uncertain times Author Arthur Boutellis Data Visuals Jose Luengo-Cabrera EPON series editor Cedric DeConing Contents Acknowledgements 5 List of figures 7 Executive summary 9 Introduction 11 1. Brief history of MINUSMA 13 2. Assessing the effectiveness of MINUSMA since 2019 17 2.1. Supporting the Peace Process 17 2.2. Supporting PoC and the re-establishment of state authority in Central Mali 20 2.3. Supporting the 18-month Malian political transition 25 2.4. The relationship between MINUSMA and other forces 27 3. Implications for MINUSMA’s mandate renewal 33 3.1. The first strategic priority: The Peace Process 34 3.2. The second strategic priority: Central Mali 35 3.3. Supporting the Malian Transition within the framework of existing two strategic priorities 36 3.4. -

MALI Northern Takeover Internally Displaces at Least 118,000 People

1 October 2012 MALI Northern takeover internally displaces at least 118,000 people Few could have predicted that Mali, long considered a beacon of democ- racy in West Africa, would in less than a year see half its territory overrun by Islamic militants and a tenth of its northern population internally dis- placed. Instability and insecurity result- ing from clashes between government forces and Tuareg separatists and pro- liferation of armed groups in northern Mali in the wake of a coup d’état have combined with a Sahel-wide food crisis to force some 393,000 Malians from their homes since January 2012, some 118,800 of whom are estimated to be Malians who fled the unrest in the northeastern city of Gao wait at a bus internally displaced. station in Bamako to return to Gao, September 2012. REUTERS/Adama Diarra Some 35,300 people are displaced across Mali’s vast three northern regions, living in town with host fami- lies or out in the open in makeshift shelters. Most of the 83,400 IDPs who have taken refuge in the south are staying with host families. Both IDPs and host families face severe shortages of food, access to health care and basic necessities. Many IDPs have lost their sources of livelihoods and children’s education has been severely jeopardised. The nascent government of national unity, which took power in August 2012 after prolonged instability, has taken some steps to respond to health, nutrition and education needs but serious concerns remain for the vast majority of the displaced who still lack access to basic services. -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Mali

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Mali - Floods DREF n° MDRML013 / PML027 Glide n° FL-2018-000140-MLI Date of issue: 04 September 2018 Expected timeframe: 3 months Expected end date: 04 December 2018 Operation start date: 04 September 2018 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: Yellow DREF allocated: CHF 215,419 Total number of people affected: 13,150 people or 2,630 Number of people to be assisted: 7,500 people households (1,500 households) - 3,000 people or 600 households (direct beneficiaries) - 4,500 people or 900 HH (indirect beneficiaries) IFRC Focal point: Luca PARODI, DM delegate for Sahel National Society contact: Mamadou Bassirou Cluster, will be project manager and overall responsible for Traore, Preparedness and Response Manager planning, implementation, monitoring, reporting and compliance Host National Society presence: Mali RC has branches in all regions and is endowed with a vast network of RDRT, NDRT, CDRT. Overall, Mali RC has 800 trained volunteers in first aid, 250 CDRT, 100 NDRT, 3 RDRT. 30 NDRT are specialized on Shelter and 180 people on EVC analysis. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International federation of Red Cross and Red Cross Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the French Red Cross Belgian Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross, Spanish Red Cross, Luxemburg Red Cross, the Netherlands Red Cross and Canadian Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Civil Protection - The Government – UN Agencies including UNICEF and OCHA. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Since 7th of August 2018, Mali has been affected by heavy rainfall, which peaked between 17 to 19 August, causing floods across the country. -

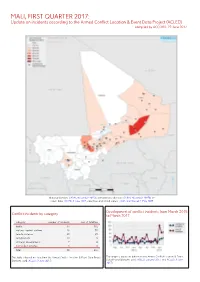

MALI, FIRST QUARTER 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 22 June 2017

MALI, FIRST QUARTER 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 22 June 2017 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 3 June 2017; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from March 2015 Conflict incidents by category to March 2017 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 34 152 violence against civilians 26 55 remote violence 20 29 riots/protests 10 0 strategic developments 7 0 non-violent activities 1 0 total 98 236 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, 3 June 2017). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, January 2017, and ACLED, 3 June 2017). MALI, FIRST QUARTER 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 22 JUNE 2017 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. Administrative divisions (based on GADM data) are reflected as of before the 2016 reform. In Bamako, 7 incidents killing 1 person were reported. The following locations were affected: Bamako, Djikoroni, Senou. -

Mali Crisis: a Migration Perspective

MALI CRISIS: A MIGRATION PERSPECTIVE June 2013 Wrien by Diana Carer Edited by Sarah Harris Review Commiee Patrice Quesada Peter Van der Auweraert Research Assistance Johanna Klos Ethel Gandia ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !! Birak Dawra UmmalAbid Smaracamp ! ! I-n-Salah Laayoune ! June 2013 ● www.iom.int ● [email protected] MALI CRISIS: A MIGR!!ATION PERSPECTIVE ! ! Smara ! Dakhlacamp Reggane Lemsid ! Illizi ! Tmassah ! BirLehlou ! Pre-crisis Patterns and Flows Marzuq ! ! ! Chegga Arak EUROPE BirMogrein Malian Diaspora ! 6 68,7863 Ghat 2,531 MALIANS FRANCE ● 2010 ASYLUM SEEKERS ! Jan - Dec 2012 Djanet ! Malian Diaspora Tajarhi 185,144 301,027 21,5893 SPAIN ● 2010 ! TOTAL MALIAN CROSS BORDER MOVEMENTS TOTAL INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPS) InAmguel INTO NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES ● as of May 2013 INSIDE MALI ● as of April 2013 228,918 as of 14 Jan 2013 ALGERIA TOTAL MALIAN REFUGEES 176,144 ! ! Taoudenni ! ! Tamanrasset FderikZouirat as of May 2013 30,000 Malian Returnees from Libya12 144,329 as of 10 Jan 2013 as of Dec 2012 11,248 assisted by IOM 4 TOTAL OTHER MOVEMENTS OF MALIANS 9,000 as of May 2012 MALI 1,500 Malian Refugees 10 as of 1 Apr 2013 registered with UNHCR Malian Diaspora 3 ! 1,500 as of 10 Jan 2013 12,815 Malian Diaspora MAURITANIA ● 2010 Djado 69,7903 ! Malian Diaspora NIGER ● 2010 Atar 17,5023 Tessalit SENEGAL ● 2010 ! Boghassa Malian Diaspora 9 ! Tinzaouaten 3 Malian Diaspora ! Malian Diaspora 68,295 15,624 Refugees BURKINA FASO ● 2010 3 15,2763 133,464 9 5 Aguelhok 10,000 Malians GUINEA ● 2010 NIGERIA ● 2010 2,497 Asylum Seekers ! Malian Diaspora as of 3 Apr 2012 inside Mali ● as of Jan 2012 STRANDED AT ALGERIAN BORDER 440,9603 Araouane COTE D’IVOIRE ● 2010 MAURITANIA ! ! Malian Diaspora Malian Diaspora 1 Arlit 3 6,0113 ! KIDAL 31,306 Tidjikdja 28,645 IDPs GABON ● 2010 REP.