Study on the Economic Developments of the EU Air Transport Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Exit of Air Berlin at the Intra- Sciencedirect German O&D Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Available online at www.sciencedirect.com 2 Author name / Transportation Research Procedia 00 (2020) 000–000 Transportation Research Procedia 00 (2020) 000–000 Transportation Research Procedia 00 (2020) 000–000 ScienceDirectScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia This paper aims to identify key demand and yield developments after the market exit of Air Berlin at the intra- ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia German O&D level. Based on this, we derive and discuss impacts and general recommendations for airline Transportation Research Procedia 52 (2021) 420–427 customers and policymaking. Even though Air Berlin played an important role in the leisure market ex Germany, this paper focuses on Air Berlin’s domestic activities only. Unlike European and worldwide O&D traffic, domestic O&Ds are characterized by a strong proportion of business travel and thus by relatively high yields, and competition 23rd EURO Working Group on Transportation Meeting, EWGT 2020, 16-18 September 2020, from indirect services is almost negligible. Moreover, the Air Berlin case is considered to be an excellent occasion to 23rd EURO Working Group on TransportationPaphos, CyprusMeeting, EWGT 2020, 16-18 September 2020, analyze competitors’ behavior as re-entry by the bankrupt carrier was very unlikely. Hence, any competitive Paphos, Cyprus response was mainly dependent on the remaining players on the actual O&D’s and on domestic O&Ds in general. Market Exit of Air Berlin: An Analysis of Competitive Pricing on Market Exit of Air Berlin: An Analysis of Competitive Pricing on Domestic O&Ds in the German Market 2. -

![Contents [Edit] Africa](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9562/contents-edit-africa-79562.webp)

Contents [Edit] Africa

Low cost carriers The following is a list of low cost carriers organized by home country. A low-cost carrier or low-cost airline (also known as a no-frills, discount or budget carrier or airline) is an airline that offers generally low fares in exchange for eliminating many traditional passenger services. See the low cost carrier article for more information. Regional airlines, which may compete with low-cost airlines on some routes are listed at the article 'List of regional airlines.' Contents [hide] y 1 Africa y 2 Americas y 3 Asia y 4 Europe y 5 Middle East y 6 Oceania y 7 Defunct low-cost carriers y 8 See also y 9 References [edit] Africa Egypt South Africa y Air Arabia Egypt y Kulula.com y 1Time Kenya y Mango y Velvet Sky y Fly540 Tunisia Nigeria y Karthago Airlines y Aero Contractors Morocco y Jet4you y Air Arabia Maroc [edit] Americas Mexico y Aviacsa y Interjet y VivaAerobus y Volaris Barbados Peru y REDjet (planned) y Peruvian Airlines Brazil United States y Azul Brazilian Airlines y AirTran Airways Domestic y Gol Airlines Routes, Caribbean Routes and y WebJet Linhas Aéreas Mexico Routes (in process of being acquired by Southwest) Canada y Allegiant Air Domestic Routes and International Charter y CanJet (chartered flights y Frontier Airlines Domestic, only) Mexico, and Central America y WestJet Domestic, United Routes [1] States and Caribbean y JetBlue Airways Domestic, Routes Caribbean, and South America Routes Colombia y Southwest Airlines Domestic Routes y Aires y Spirit Airlines Domestic, y EasyFly Caribbean, Central and -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

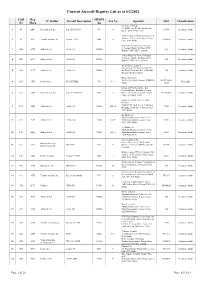

To Access the List of Registered Aircraft As on 2Nd August

Current Aircraft Registry List as at 8/2/2021 CofR Reg MTOM TC Holder Aircraft Description Pax No Operator MSN Classification No Mark /kg Cherokee 160 Ltd. 24, Id-Dwejra, De La Cruz Avenue, 1 41 ABW Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-28-160 998 4 28-586 Aeroplane (land) Qormi QRM 2456, Malta Malta School of Flying Company Ltd. Aurora, 18, Triq Santa Marija, Luqa, 2 62 ACL Textron Aviation Inc. Cessna 172M 1043 4 17260955 Aeroplane (land) LQA 1643, Malta Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 3 1584 ACX Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 544 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 4 1583 ACY Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 582 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Air X Charter Limited SmartCity Malta, Building SCM 01, 5 1589 ACZ Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 4th Floor, Units 401 403, SCM 1001, 590 Aeroplane (land) Ricasoli, Kalkara, Malta Nazzareno Psaila 40, Triq Is-Sejjieh, Naxxar, NXR1930, 001-PFA262- 6 105 ADX Reno Psaila RP-KESTREL 703 1+1 Microlight Malta 12665 European Pilot Academy Ltd. Falcon Alliance Building, Security 7 107 AEB Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-34-200T 1999 6 Gate 1, Malta International Airport, 34-7870066 Aeroplane (land) Luqa LQA 4000, Malta Malta Air Travel Ltd. dba 'Malta MedAir' Camilleri Preziosi, Level 3, Valletta 8 134 AEO Airbus S.A.S. A320-214 75500 168+10 2768 Aeroplane (land) Building, South Street, Valletta VLT 1103, Malta Air Malta p.l.c. -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research June 2008 Porz-Wahnheide Linder Höhe 51147 Köln Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-06-20 Release: 1.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 1.2 Save date: 2008-06-20 Total pages: 224 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.0 2008-06-06 Final Report (Annual 2007) 1.1 2008-06-09 chapter 2.1.7 PSO data update 1.2 2008-06-16 layout items 2.0 Sept 2008 full year 2007 update expected in September 2008 Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or the Transport and Energy DG's views. -

Aero Ae 45 & Ae

This production list is presented to you by the editorial team of "Soviet Transports" - current to the beginning of January 2021. Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected] Aero Ae 45 & Ae 145 181 Ae 45 built by Aero at Prague-Vysocany from 1947 to 1951 The c/n consisted of the year of manufacture and a sequential number. 1 OK-BCA Ae 45 Aero f/f 21jul47 the first prototype; rgd 11sep47; underwent trials with the SVZÚ sep47 OK-BCA Ae 45 Ministers. dopravy trf unknown Ministry of Transport OK-BCA Ae 45 CSA trf unknown canx 1953 2 OK-CCA Ae 45 Aero rgd 09apr48 the second prototype; f/f 12mar48 OK-CCA Ae 45 Celulozka Bratisl. trf unknown Celulozka Bratislava; canx 1958 not known Ae 45 Czechoslovak AF trf unknown 49 003 G-007 (1) Ae 45 Hungarian AF d/d 15may49 HA-AEB Ae 45 MÉM Rep. Szolgálat trf 06apr52 Hungarian Flying Association; damaged 29apr52 when the landing gear broke HA-AEB Ae 45 OMSZ trf 18jun57 Hungarian Air Ambulance; w/o (or canx ?) 22nov62 49 004 OK-DCB Ae 45 rgd 21apr49 canx to Italy I-CRES Ae 45 Aero Club Milano rgd 18jul59 Aero Club Milano of Linate; owner also reported as Franco Rol; based at Torino; canx 1970 F-GFYA Ae 45 Pierre Cavassilas res aug88 Pierre Cavassilas of Chavenay; possibly never fully registered F-AZJX Ae 45 Pierre Cavassilas rgd 08jul94 seen Chavenay 20may94 with a 'W' taped over the 'A' of the registration; still current in 2007; under restoration near Paris in 2008; was to be reflown jan09; seen Compiègne 19jun09 and 27jun09 in all-grey c/s with large blue registration, in great condition; seen Soissons-Courmelles 28may12 with smaller black registration; l/n Compiègne 15jun13, active 49 005 OK-DCA Ae 45 rgd 23apr49 I-AERA Ae 45 Luigi Leone rgd 11oct61 based at Torino 49 006 HB-EKF Ae 45 Mr. -

Recull De Premsa

5 Recull de Premsa Dimecres, 14 De Gener De 2015 6 3 4 EL PUNT AVUI DIMECRES, 14 DE GENER DEL 2015 GIRONÈS | Comarques Gironines | 37 Tolosa, Palma, Eivissa i Lisboa. L’estrena de l’aero- port pirinenc, però, es va Air Andorra oferirà el vol endarrerir fins al 8 de ge- ner i de moment Air An- dorra –l’única companyia comercial que hi havia mostrat interès– no hi Girona-Madrid abans de març opera. La companyia aèria es queixa dels successius a La companyia, de nova creació, explica que ha decidit centrar la seva estratègia en aquesta ruta i retards de l’obertura –“al a juliol estàvem a punt i vam ajornar els seus plans a l’aeroport de la Seu El vol serà diari i s’efectuarà en un avió de 74 places haver de paralitzar-ho tot”–i sobretot denuncien que l’adjudicació del servei Lurdes Artigas GIRONA de handling (assistència a terra) s’ha fet només per L’ajornament del llança- sis mesos i, asseguren, ment d’Air Andorra a l’ae- sense concurs públic. “Ai- roport de la Seu –on vol es- xò no ens dóna garanties tablir la seva principal ba- de continuïtat ni tampoc se d’operacions– podia ha- seguretat, ja que creiem ver fet témer que l’anun- que alguna empresa pot ciat vol diari Girona-Ma- impugnar la designació”, drid d’aquesta companyia assenyalen. És per això de nova creació corria pe- que, mentre estudien què rill. Des de la companyia fer a la Seu, han prioritzat aèria, però, afirmen just el l’arrancada del Girona- contrari. -

Procedure for the Temporary Limitation of the Airport

Procedure - TEMPORARY LIMITATION OF THE AIRPORT CAPACITY FURTHER TO OPERATIONAL Rev. 5 dated IRREGULARITIES 18/10/2019 (TRANSLATION PROVIDED FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY - IN CASE OF ANY CONFLICT, THE ITALIAN TEXT SHALL PREVAIL) PROCEDURES FOR THE TEMPORARY LIMITATION OF THE AIRPORT CAPACITY FURTHER TO OPERATIONAL IRREGULARITIES Temporary limitation of the airport capacity further to operational irregularities Page 1 of 20 Procedure - TEMPORARY LIMITATION OF THE AIRPORT CAPACITY FURTHER TO OPERATIONAL Rev. 5 dated IRREGULARITIES 18/10/2019 (TRANSLATION PROVIDED FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY - IN CASE OF ANY CONFLICT, THE ITALIAN TEXT SHALL PREVAIL) Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 3 1.1. Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 3 2. FIUMICINO AIRPORT’S CAPACITY .................................................................. 4 2.1. Sudden limitation on the capacity of the airport(LIMITATION WITH A DURATION OF LESS THAN 2 HOURS) ..................................................................................................... 4 2.1.1 Tactical handling further to sudden limitation of the capacity of the airport ..................... 5 3. AIRPORT CAPACITY CONTROL COMMITTEE (ACC) ......................................... 8 3.1. General duties of the committee members ................................................................10 3.2. Action of the committee -

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura Pl 1928

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 1928 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 135 tal-25 ta’ Ġunju 2018 mill-Ministru għat-Trasport, Infrastruttura u Proġetti Kapitali. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra TRANSPORT MALTA Annual Report 2017 transport.gov.mt TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF TRANSPORT MALTA 4 MISSION STATEMENT 5 MAIN OBJECTIVES AND POLICIES 6 INTEGRATED TRANSPORT STRATEGY DIRECTORATE 7 PORTS AND YACHTING DIRECTORATE 10 MERCHANT SHIPPING DIRECTORATE 26 ROADS AND INFRASTRUCTURE DIRECTORATE 37 LAND TRANSPORT DIRECTORATE 45 CIVIL AVIATION DIRECTORATE 60 CORPORATE SERVICES DIRECTORATE 76 ENFORCEMENT DIRECTORATE 86 INFORMATION & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORATE 100 TRANSPORT MALTA | Annual Report 2017 | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report covers the activities of the Authority for Transport in Malta for the year ending 31st December 2017. This was the eighth year of operation for the Authority, which was set up on the 1st of January 2010 following the enactment of the Authority for Transport in Malta Act (Act XV) of 2009. The major accomplishments of the operations of Transport Malta (TM) can be summarised as follows: Merchant Shipping As at end December 2017, the number of ships registered under the Merchant Shipping Act was 8,123 with a total gross tonnage of 75.2 million. This represents a healthy growth rate of 8% over the previous year, with Malta maintaining its position as the largest register in Europe and one of the 10 largest registers in the world in terms of gross tonnage. The Directorate has also further strengthened its presence in the super yacht sector. -

The Airline That Knows Greece Best We Are … AEGEAN

The airline that knows Greece best We are … AEGEAN Full service carrier, Greece’s ………. ………. largest airline focused on quality since 2008 services & efficiency We fly to ………. We own 61 aircraft ………. 145 destinations in 40 countries 7 times awarded Star Alliance ………. as Best Regional ………. member Airline in Europe since 2010 We are … AEGEAN Acquisition of ………. Olympic Air in ………. 6 hubs in Greece and 2013 1 in Cyprus Total coverage of all ………. Scheduled & charter, Greek destinations, ………. even in small islands short & medium haul (via Olympic Air) services in Europe & Middle East Timeline of key events, evolution of passenger traffic 2016 2015 Delivery of 7 14,0 6th time new aircraft awarded by A320ceo Skytrax 12,5 13,0 2011 2013 Intl traffic Olympic Air 11,6 2003 exceeds Acquired 12,0 First Year with domestic for Profits before Taxes 2007 the fist time Listing in Stock 11,0 Market, First 2010 10,2 2003 A320 2005 Aegean joins Low Cost Carriers Deliveries Lufthansa Star Alliance enter Greek Market 10,0 Agreement, 8,8 2001 Airbus A320 Merger with Order 9,0 Cronus, First Intl Olympic Flights 1999/2000 8,0 Air Greece 2002–2003 acquisition Olympic and Aegean sole competitors 6,6 6,5 6,2 6,1 7,0 5,9 May 1999 Domestic 5,2 6,0 Deregulation. Launch of Scheduled 4,5 Million of Passengers 5,0 Flights International 4,0 3,6 4,0 2,8 2,5 3,0 2,4 2,0 1,5 0,3 Domestic 1,0 0,0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 20164 2016 Report destinations available aircraft 61 145 16,2mil.