An Historical Survey of the Development of Education for Special Types in Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report of the Department of Public Welfare

Public Document No. 17 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF Public Welfare FOR THE Year ending November 30, 1927 Publication of this Document approved by the Commi88ion on Admimhi 2M. 5-'28. Order 2207. T^-,' u m J f Cfte Commontoealrt) of illas(£facf)UfiJett£^. I DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WELFARE. To the Honorable Senate and House of Representaiives: The Eighth Annual Report of the Department of PubUc Welfare, covering the year from December 1, 1926, to November 30, 1927, is herewith respectfully ! presented. RICHARD K. COXAXT, Commissioner of Public Welfare. 37 State House, Boston. Present Members of the Advisory Board of the Department of Public Welfare. Date of Original Appointment Name Residence Term Expires December 10, 1919 A. C. Ratshesky .... Boston . December 10, 1928 December 10, 1919 Jeffrey R. Brackett .... Boston . December 10. 1928 December 10, 1919 George Crompton .... Worcester . December 10, 1930 December 10, 1919 George H. McClean . Springfield . December 10, 1930 December 10, 1919 Mrs. Ada Eliot Sheffield . Cambridge . December 10, 1929 December 10, 1919 Mrs. Mary P. H. Sherburne . Brookline . December 10, 1929 Divisions of the Department of Public Welfare. Division of Aid and Relief: Frank W. Goodhue, Director. Miss Flora E. Burton, Supervisor of Social Service, Mrs. Elizabeth F. Moloney, Supervisor of Mothers' Aid. Edward F. Morgan, Supervisor of Settlements. Division of Child Guardianship: Miss Winifred A. Keneran, Director. Division of Juvenile Training: Charles M. Davenport, Director. Robert J. Watson, Executive Secretary. Miss Almeda F. Cree, Superintendent, Girls' Parole Branch. John J. Smith, Superintendent, Boys' Parole Branch. Subdivision of Private Incorporated Charities: Miss Caroline J. Cook, Supervisor of Incorporated Charities. -

9Th to 16Th Annual Report of the Lyman and Industrial Schools

Public Document No. 18 THIRTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT OP THE TRUSTEES <v. - Lyman and Industrial Schools (Formerly known as Trustees of the State Primary and Reform Schools), Year ending November 30, 1907. k% • mm 1 BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1908. Approved by The State Boafd ok Publtoation. CONTENTS. PAGE Trustees' Report ox Lyman School, 6 Trustees' Report on State Industrial School, 16 Appendix A, Report of Treasurer and Receiver-General on Trust Funds, 27 Appendix B, Report of Officers of the Lyman School: — Report of Superintendent 39 Report of Superintendent of Lyman School Probationers, .... 45 Report of Physician, 58 Statistics concerning Boys, 60 Financial Statement, 70 Farm Account, 74 Valuation of Property, 75 List of Salaried Officers, 77 Statistical Form for State Institutions, 79 AFPBNDI3 C, Report of Officers of the State Industrial School: — Report of Superintendent, 83 Report of Superintendent of Industrial School Probationers, ... 91 Report of Physician, 98 Statistics concerning Girls 99 Financial Statement, 120 Farm Account, 124 Valuation of Property, 125 List of Salaried Officers 126 List of Volunteer Visitors, 12S Statistical Form for State Institutions, 130 Commflnforaltjj of llfassacjfnsttis. Lyman and Industkial Schools. TRUSTEES. M. H. WALKER, Westborough, Chairman. ELIZABETH G. EVANS, Boston, Secretary. SUSAN C. LYMAN, Waltham. JAMES W. McDONALD, Marlborough. GEORGE H. CARLETON, Haverhill. MATTHEW B. LAMB, Worcester. CARL DREYFUS, Boston. HEADS OP DEPARTMENTS. ELMER L. COFFEEN, Superintendent of Lyman School. THOMAS H. AYER, Visiting Physician of Lyman School. WALTER A. WHEELER, Superintendent of Lyman School Probationers. FANNIE F. MORSE, Superintendent of State Industrial School. C C. BECKLEY, Visiting Physician of State Industrial School. -

1St to 8Th Annual Report of the Trustees of the Lyman And

PUBLIC DOCUMENT .... .... No. 18. SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT THE TRUSTEES Lyman and Industrial Schools (Formerly known as Trustees of the State Primary and Reform Schools), Year ending September 30, 1901, BOSTON : WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1902. CONTENTS PAGB Trustees' Report on Lyman School, 5 Trustees' Report on State Industrial School, 15 Report of Treasurer of Trust Funds, 23 Report of Superintendent of Lyman School, 31 Statistics of Lyman School, 35 Report of Principal of Schools of Lyman School, 46 Report of Instructors of Sloyd, Lyman School, 49 Report of Instructor of Advanced Manual Training, 51 Report of Instructor in Drawing and Wood Carving, 53 Report of Instructor of Physical Training, Lyman School, 55 Report of Physician, Lyman School, 57 Report of Manager of Berlin Farmhouse, 58 Financial Statement, Lyman School, 60 Report of the Farmer, Lyman School, 74 Report of Berlin Farmer, 76 Farm Account, Lyman School, 78 Valuation of Property, Lyman School, 82 Schedule of Salaried Officers, Lyman School, 86 List of Superintendents, Lyman School, 89 List of Trustees, Lyman School, 90 Report of Superintendent of Visitation of Lyman School Probationers, . 92 Report of Superintendent of State Industrial School, 101 Statistics of State Industrial School, , 103 Financial Statement of State Industrial School, 115 Supervisor of Schools of State Industrial School, 127 Report of Physician of State Industrial School, 128 Commonhxealtfy ai lltassaxfrnaeite REPORT OF TRUSTEES LYMAN AND INDUSTEIAL SCHOOLS. To His Excellency the Governor and the Honorable Council. The undersigned, trustees of the Lyman and Industrial Schools, respectfully present the appended report for the year ending Sept. -

Gazette 1905 - 1909

Index: Middleboro Gazette 1905 - 1909 Introduction The Middleboro Gazette Index, 1905 - 1909 is a guide to the information contained within the Middleboro Gazette during the period January 1905 through December 1909. The information is as it appears in the newspaper and no attempt has been made to verify that the information given in the newspaper is accurate. The focus of the index is on the communities of Middleboro and Lakeville, Massachusetts. News from outside these geographic areas is included only if there is a direct link to these towns, i.e., Phineas T. Barnum and the Little People. Special notations are used within the index to designate editorials (e), letters (l), tables (t), photographs (p) and illustrations (i). Authors of editorials or letters are cited either within the headline or in parentheses immediately following either (e) or (l). The often informal nature of reporting presents special challenges to researchers. Additional information about specific businesses, town departments or other concerns can be located under general headines, i.e., Railroads, Streets, etc. Names are a particular challenge in a compilation of this kind. Multiple spellings, misspellings and incomplete names are just a few of the hurdles that must be overcome in order to glean every bit of information contained within the pages of the Gazette. For example, Mr. Elnathan W. Wilbur may be cited as any or all of the following: Wilbur, Elnathan W. Wilbur, Elnathan Wilbur, E.W. Wilbur, E. Wilbur (Mr) Wilbur (Captain) Mr. Wilbur’s last name may also be spelled, Wilbor, Wilber, Wilbour or Wilbur. In addition married women were also frequently cited as Mrs. -

1885-Senate-01-January .Pdf (8.690Mb)

T IIE JOURNAL OF THE SENATE FOR THE YEAR 1885 PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE SENATE. BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 P o s t O f f ic e S q u a r e . 1885. JOURNAL OF THE SENATE. At a General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachu setts, begun and holden at Boston on the first Wednesday, being the seventh day, of January, in the year one thou sand eight hundred and eighty-five, and the one hundred and ninth of the independence of the United States of America, the following-named members-elect of the Sen ate, having been duly summoned by the Executive, ap peared, to wit: — Hon. Messrs. Wesley A. Gove, . in the First Ezra J. Trull, . Second Alexander B. McGahey T h ird John F. Andrew, F o u rth Suffolk Henry F. Naphen, . F ifth D istricts. Albert E. Pillsbury, Sixth Paul H. Ivendricken, Seventh and George L. Burt, E ig h th Hon. Messrs. Josiah C. Bennett, . in the F irst William Cogswell, . Second William H. Tappan, T h ird E ssex George W . Morrill, F o u rth D istricts. Charles B. Emerson, F ifth and Newton P. Frye, Sixth Hon. Messrs. Eleazar Boynton, . in the F irst Augustus E. Scott, . Second Henry J. Wells, T hird Francis Bigelow, F o u rth M iddlesex George W . Sanderson, F ifth D istricts. Jo h n M. H arlow , Sixth and George A. Ma^len, . Seventh Hon. Messrs. Martin V. B. Jefferson, . in the First Arthur F. Whitin, . -

Summary of Existing Natural and Historic Resources in Westborough

5. NATURAL AND HISTORIC RESOURCES Summary of Existing Natural and Historic Resources in Westborough Strengths Concerns • Woodlands cover more than 41% (more than 5,600 • More than half of the Town’s remaining woodlands acres) of the Town. are unprotected from potential future development. • Over 1,900 acres of wetlands exist in the Town. • Continued growth will result in the loss of farmland, • The Town has several productive groundwater forest, and other open space. aquifers that meet the water needs of the local • Although the water quality of the Assabet River has population. improved greatly over the past decades, the river • Westborough has several attractive water bodies still suffers from excessive nutrient loading. including the Assabet and Sudbury Rivers, Lake • New development threatens water resources and Chauncy, Hocomonco Pond, and the Westborough other natural resources as a result of increased non- Reservoir. point source water pollution, habitat fragmentation, • The Town has over 400 historic buildings, sites erosion, and other impacts. and properties including a National Register • New development may alter the historic character of Historic District downtown. some sections of the Town. • The Cedar Swamp Archaeological District is the • As real estate values increase, there will be more second largest archaeological district in the state. pressure to develop marginal lands and to tear down and replace historic structures. Westborough’s natural and cultural resources provide an important counterbalance to the Town’s developed areas. Undeveloped farms, forests, and wetlands provide clean water, clean air, wildlife habitat, and scenic views. Historic buildings, sites, and landscapes provide a glimpse into the Town’s agrarian and industrial past and help define the Town’s character. -

Rainsford Island: a Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect And

© RAINSFORD ISLAND A Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect and Private Activism First Printing September 3, 2019 Revision December 6, 2020 Copyright: May 13, 2019 William A. McEvoy Jr, & Robin Hazard Ray Dedicated to my wife, Lucille McEvoy 2 © Table of Contents Preface by Bill McEvoy ....................................................................................................................... 4 Introductory Note by Robin Hazard Ray ................................................................................................ 1. The Island to 1854 .................................................................................................................................... 9 2. The Hospital under the Commonwealth, 1854–67 ............................................................................... 14 3. The Men’s Era, 1872–89 ......................................................................................................................... 31 4. The Women’s Era, 1889–95 .................................................................................................................. 43 5. The Infants’ Summer Hospital, 1894–98 ............................................................................................... 60 6. The House of Reformation, 1895–1920 ................................................................................................. 71 7. The Dead of Rainsford Island ........................................................................................................ 94 Epilogue -

Annual Report of the Department of Public Welfare, Covering the Year from December 1, 1932, to November 30, 1933, Is Herewith Respectfully Presented

Public Document No. 17 ©I?? (Eomttumwtttlli? of MmButtymtttz ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF Public Welfare FOR THE Year Ending November 30, 1933 parts i, ii, and iii Publication of this Document approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance 500 6-'34. Order 1344. ®f)e Commontoealtf) of ifttastfacfjutfetts DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WELFARE Richard K. Conant, Commissioner To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives: The Fourteenth Annual Report of the Department of Public Welfare, covering the year from December 1, 1932, to November 30, 1933, is herewith respectfully presented. Members of the Advisory Board of the Department of Public Welfare Date of Original Date of Appointment Name Residence Expiration December 10, 1919 Jeffrey R. Brackett Boston . December 1, 1934 December 10, 1919 George Crompton Worcester . December 1, 1936 December 10, 1919 Mrs. Ada Eliot Sheffield .... Cambridge December 1, 1935 October 9,1929 John J. O'Connor . .... Holyoke . December 1, 1936 July 1, 1931 Harry C. Solomon, M.D Boston . December 1, 1934 December 21, 1932 Mrs. Ceeilia F. Logan .... Cohasset . December 1, 1935 Divisions of the Department of Public Welfare Boston Division of Aid and Relief : Room 30, State House Frank W. Goodhue, Director Miss Flora E. Burton, Supervisor of Social Service Mrs. Elizabeth F. Moloney, Supervisor of Mothers' Aid Edward F. Morgan, Supervisor of Settlements John B. Gallagher, Supervisor of Relief Bureau of Old Age Assistance: 15 Ashburton Place Francis Bardwell, Superintendent Division of Child Guardianship: Room 43 r State House Miss Winifred A. Keneran, Director * Division of Juvenile Training: 41 Mt. Vernon Stiee't » Charles M. -

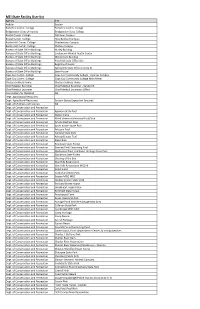

MEI State Facilities Inventory List.Xlsx

MEI State Facility User list Agency Site Auditor Boston Berkshire Comm. College Berkshire Comm. College Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State College Bristol Comm. College Fall River Campus Bristol Comm. College New Bedford Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Charlestown Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Chelsea Campus Bureau of State Office Buildings Hurley Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Lindemann Mental Health Center Bureau of State Office Buildings McCormack Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Pittsfield State Office Site Bureau of State Office Buildings Registry of Deeds Bureau of State Office Buildings Springfield State Office Liberty St Bureau of State Office Buildings State House Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College ‐ Hyannis Campus Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College Main Meter Chelsea Soldiers Home Chelsea Soldiers Home Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiner ‐ Sandwich Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiners Office Commission for the Blind NA Dept. Agricultural Resources Dept. Agricultural Resources Eastern States Exposition Grounds Dept. of Children and Families NA Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Agawam State Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Aleixo Arena Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Allied Veterans Memorial Pool/Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Amelia Eairhart Dam Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ames Nowell State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Artesani Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashland State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashuwillticook Trail Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bajko Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Beartown State Forest Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bennett Field Swimming Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Blackstone River and Canal Heritage State Park Dept. -

9Th to 16Th Annual Report of the Lyman and Industrial Schools

PUBLIC DOCUMENT .... .... No. 18. TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT THE TRUSTEES Lyman and Industrial Schools (Formerly known as Trustees ok the State Primary and Reform Schools), FOR THE Year ending November 30,' 1906. BOSTON : WRIGHT A POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office SQUARE. 1907. Approved by The Statf Board of Publication- CONTENTS PAGE Trustees' Report on Lyman School, 6 Trustees' Report on State Industrial School, 16 Appendix A, Report of Treasurer and Receiver-General on Trust Funds, 23 Appendix B, Report of Officers of the Lyman School: — Report of Superintendent, 33 Report of Superintendent of Lyman School Probationers, .... 42 Report of Physician, 56 Statistics concerning Boys, 57 Financial Statement 67 Farm Account, 71 Valuation of Property, 72 List of Salaried Officers, 74 Statistical Form for State Institutions, 76 Appendix C, Report of Officers of the State Industrial School : — Report of Superintendent, 81 Report of Physician, 88 Report of Oculist and Aurist, 90 Report of Superintendent of Industrial School Probationers, .... 92 Statistics concerning Girls, 99 Financial Statement, 119 Farm Account, 123 Valuation of Property, 124 List of Salaried Officers 125 List of Volunteer Visitors 127 Statistical Form for State Institutions, 128 Commcrctoealtb of glassaclnisflis, Lyman and Industrial Schools. TRUSTEES. M. H. WALKER, Westborough, Chairman. ELIZABETH G. EVANS, Boston, Secretary. M. J. SULLIVAN, Chicopee. SUSAN C. LYMAN, Waltham. JAMES W. McDONALD, Marlborough. GEORGE H. CARLETON, Haverhill. CHARLES G. WASHBURN, Worcester. HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS. THEODORE F. CHAPIN, Superintendent of Lyman School THOMAS II . AYER, Visiting Physician of Lyman School. « WALTER A. WHEELER, Superintendent of Lyman School Probationers. FANNIE F. MORSE, Superintendent of State Industrial School. -

Annual Report of the Trustees of Massachusetts Training Schools for The

Public Document No. 93 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES OF MASSACHUSETTS TRAINING SCHOOLS FOR THE Year Ending November 30, 1929 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WELFARE DATE DUE Publication of this Document approved by the Commission cn Administration and Finance 850. 5-'30. Order 9074. : CONTENTS Page Report of the Trustees . 3 Reports of Officers and Statistics: Report of the Psychiatric Work ...... 4 Lyman School for Roys: Superintendent's Report ...... 6 Physician's Report ....... 7 Statistics concerning Roys . 9 Treasurer's Report ....... 12 Valuation of Property . 13 Statistical Form for State Institutions .... 13 Industrial School for Roys: Superintendent's Report ... 14 Physician's Report ....... 15 Statistics concerning Roys . 17 Treasurer's Report ....... 19 Valuation of Property ....... 20 Statistical Form for State Institutions .... 20 Roys Parole Rranch Superintendent's Report ...... 21 Statistics concerning Work of Roys Parole Rranch . 21 Industrial School for Girls: Superintendent's Report ...... 24 Physician's Report ....... 26 Statistics concerning Girls ...... 27 Treasurer's Report ....... 30 Valuation of Property ....... 31 Statistical Form for State Institutions .... 31 Girls Parole Rranch: Superintendent's Report . ... 31 Statistics concerning Work of Girls Parole Rranch . 35 Trust Funds 36 Efje Commontoealtf) of Jfflastfacfmsetts; DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WELFARE DIVISION OF JUVENILE TRAINING TRUSTEES OF MASSACHUSETTS TRAINING SCHOOLS TRUSTEES CHARLES M. DAVENPORT, Roston, Director. JAMES W. McDONALD, Marlborough, Chairman. CLARENCE J. McKENZIE, Winthrop, Vice-Chairman. JOSEPHINE RLEAKIE COLRURN, Wellesley Hills. AMY E. TAYLOR, Lexington. EUGENE T. CONNOLLY, Swampscott. WILLIAM L. S. RRAYTON, Fall River. RANSOM C. PINGREE, Roston. RENJAMIN F. FELT, Melrose. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY RORERT J. WATSON Room 305, 41 Mt. Vernon Street, Roston. HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS. -

Annual Report of the Department of Public Welfare. Massachusetts

Public Document No. 17 QJlje QjDtnmnnuiealtlj of MussmifrntttB ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF Public Welfare FOR THE Year ending November 30, 1930 Publication of this Document approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance 2800 6-*31 Order 2709 €t)e Commtmtoeatti) of ffia$$act>n$ttt$ DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WELFARE. Richard K. Conant, Commissioner, Representatives: To the Honorable Senate and House of Public Welfare covering the The Eleventh Annual Report of the Department of 30, 1930, is herewith respectfully year from December 1, 1929, to November presented. Department of Public Welfare. Members of the Advisory Board of the Date of 1 Expiration ^PPoiSint Name Residence Boston December 10, 1931 December 10, 1919 AC. Ratshesky . December 10, 1931 R. Brackett December 10, 1919 Jeffrey December 1, 1933 George Crompton Worcester' December 10, 1919 SoSnafteS September 19, 1929 December 10, 1919 *GeorgeHMcClean December 10, 1932 Eliot Sheffield .... ^mCambridgebridge December 10, 1919 Mrs. Ada December 10, 1932 Brooklme . Mrs. Mary P. H. Sherburne . December 10, 1919 Holyoke December 1, 1933 October 9, 1929 John J. O'Connor . Divisions of the Department of Public Welfare. Boston House Division of Aid and Relief: Room 30, State Frank W. Goodhue, Director Miss Flora E. Burton, Supervisor of Social beryice Mothers Aid Mrs. Elizabeth F. Moloney, Supervisor of Edward F. Morgan, Supervisor of Settlements House Division of Child Guardianship: Room 43, State Miss Winifred A. Keneran, Director Division of Juvenile Training: 41 Mt. Vernon Street Charles M. Davenport, Director Executive Secretary Robert J. Watson, , , . ^ , Branch Miss Almeda F. Cree, Superintendent, Girls' Parole Parole Branch John J.