Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3082 L2/06-121

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming Javier Diaz The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2966 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MEANING BEYOND WORDS: A MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF AFRO-CUBAN BATÁ DRUMMING by JAVIER DIAZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2019 2018 JAVIER DIAZ All rights reserved ii Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor in Musical Arts. ——————————— —————————————————— Date Benjamin Lapidus Chair of Examining Committee ——————————— —————————————————— Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Peter Manuel, Advisor Janette Tilley, First Reader David Font-Navarrete, Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz Advisor: Peter Manuel This dissertation consists of a musical analysis of Afro-Cuban batá drumming. Current scholarship focuses on ethnographic research, descriptive analysis, transcriptions, and studies on the language encoding capabilities of batá. -

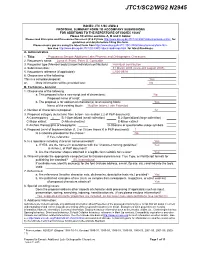

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N2945

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2945 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Proposal to Encode Additional Latin Phonetic and Orthographic Characters 2. Requester's name: Lorna A. Priest, Peter G. Constable 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual contribution 4. Submission date: 31 March 2005 (revised 9 August 2005) 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): L2/05-097R 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes or, More information will be provided later: No B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): No Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Modifier letters, Latin Extended 2. Number of characters in proposal: 12 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary x B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

Collective Difference: the Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Collective Difference: The Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N. Stallings Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COLLECTIVE DIFFERENCE: THE PAN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COMPOSERS AND PAN-AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN MUSIC, 1925-1945 By STEPHANIE N. STALLINGS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stephanie N. Stallings All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephanie N. Stallings defended on April 20, 2009. ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to my dissertation advisor, Denise Von Glahn. Without her excellent guidance, steadfast moral support, thoughtfulness, and creativity, this dissertation never would have come to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my dissertation committee, Charles Brewer, Evan Jones, and Douglass Seaton, for their wisdom. Similarly, each member of the Musicology faculty at Florida State University has provided me with a different model for scholarly excellence in “capital M Musicology.” The FSU Society for Musicology has been a wonderful support system throughout my tenure at Florida State. -

Roberto Sierra's Missa Latina: Musical Analysis and Historical Perpectives Jose Rivera

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Roberto Sierra's Missa Latina: Musical Analysis and Historical Perpectives Jose Rivera Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ROBERTO SIERRA’S MISSA LATINA: MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND HISTORICAL PERPECTIVES By JOSE RIVERA A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Jose Rivera All Rights Reserved To my lovely wife Mabel, and children Carla and Cristian for their unconditional love and support. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work has been possible with the collaboration, inspiration and encouragement of many individuals. The author wishes to thank advisors Dr. Timothy Hoekman and Dr. Kevin Fenton for their guidance and encouragement throughout my graduate education and in the writing of this document. Dr. Judy Bowers, has shepherd me throughout my graduate degrees. She is a Master Teacher whom I deeply admire and respect. Thank you for sharing your passion for teaching music. Dr. Andre Thomas been a constant source of inspiration and light throughout my college music education. Thank you for always reminding your students to aim for musical excellence from their mind, heart, and soul. It is with deepest gratitude that the author wishes to acknowledge David Murray, Subito Music Publishing, and composer Roberto Sierra for granting permission to reprint choral music excerpts discussed in this document. I would also like to thank Leonard Slatkin, Norman Scribner, Joseph Holt, and the staff of the Choral Arts Society of Washington for allowing me to attend their rehearsals. -

Salt Lake City August 1—4, 2019 Nfac Discover 18 Ad OL.Pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM

47th Annual National Flute Association Convention Salt Lake City August 1 —4, 2019 NFAc_Discover_18_Ad_OL.pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Custom Handmade Since 1888 Booth 110 wmshaynes.com Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 214 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2019, Salt available in Carbon Fibre. Lake City! Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery www.wisemanlondon.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ............................................................... -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

ISO/IEC JTC1 SC2 Working Group 2 and UTC FROM: Deborah

TO: ISO/IEC JTC1 SC2 Working Group 2 and UTC FROM: Deborah Anderson, UC Berkeley DATE: 8 April 2006 RE: Expert Input on “Proposal to add Mayanist Latin letters to the UCS” N3028 (=L2/06-028) Executive Summary: This document provides feedback received on the evidence for uppercase tresillo and cuatrillo and whether these characters are should be included in Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646. The initial query went out over the email list LinguistList. A number of experts were sent email queries separately. There were nine responses, included below. Evidence for Attestation Michael Dürr (#1) and Thomas Larsen (#2) both checked the sources available to them (including manuscripts, facsimile editions, and printed books) and have found that the uppercase forms do occur, albeit rarely and not consistently. As noted by Larsen (#2), uppercase—which is a lowercase modified in various ways—appears at the beginning of paragraphs in the Annals of the Cakchiquels, in handwritten dictionary entries in Calepino en Lengua Cakchiquel, and for cited words in Compendio de Nombres en Lengua Cakchiquel. (Campbell [#3] also mentions attempts at printing case distinctions.) Reasons to Encode (or Not) in the UCS In spite of the inconsistency in their use, most respondents were in support of including these characters in the UCS for the following reasons: • Though the original texts do not use uppercase in the conventional way (i.e., at the beginning of sentences, etc.), the characters’ inclusion would make it possible to print the original text accurately (Maxwell #4, -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3094 L2/06-133

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3094 L2/06-133 2006-04-16 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Discussion of the Mayanist Latin letter CUATRILLO WITH COMMA Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2006-04-16 On the Unicore discussion list, Karl Pentzlin asked: “Why do the LATIN capital/small CUATRILLO WITH COMMA need their own codepoints, instead of using LATIN capital/small CUATRILLO + U+0326 COMBINING COMMA BELOW?” The mark does not behave like a combining comma below. First note that real G and real g (not the cuatrillo) are found with U+0327 COMBINING CEDILLA in Latvian orthography, where the cedilla is conventionally drawn with a comma-shape. But with the lower-case g it is not drawn underneath the g, but rather is turned and drawn above it. This is an aside, but it’s just something to note. Second, note that in Figures 18 and 19 of N3082 the true cedilla is drawn with a comma-like shape. This is sort of “typographic handwriting”, though since neither of those two samples shows the CUATRILLO WITH COMMA... well, let’s just say there’s room for confusion that would be better avoided. Third, see Figure 20 of N3082, where a glyph variant of CUATRILLO WITH COMMA is shown with a horizontal bar rather than with a comma. If encoded as a unique character, font designers can more easily make the choice to draw it this way; it’s not at all reasonable to expect COMBINING COMMA BELOW to render in this fashion. -

Gershwin, Copland, Lecuoña, Chávez, and Revueltas

Latin Dance-Rhythm Influences in Early Twentieth Century American Music: Gershwin, Copland, Lecuoña, Chávez, and Revueltas Mariesse Oualline Samuels Herrera Elementary School INTRODUCTION In June 2003, the U. S. Census Bureau released new statistics. The Latino group in the United States had grown officially to be the country’s largest minority at 38.8 million, exceeding African Americans by approximately 2.2 million. The student profile of the school where I teach (Herrera Elementary, Houston Independent School District) is 96% Hispanic, 3% Anglo, and 1% African-American. Since many of the Hispanic students are often immigrants from Mexico or Central America, or children of immigrants, finding the common ground between American music and the music of their indigenous countries is often a first step towards establishing a positive learning relationship. With this unit, I aim to introduce students to a few works by Gershwin and Copland that establish connections with Latin American music and to compare these to the works of Latin American composers. All of them have blended the European symphonic styles with indigenous folk music, creating a new strand of world music. The topic of Latin dance influences at first brought to mind Mexico and mariachi ensembles, probably because in South Texas, we hear Mexican folk music in neighborhood restaurants, at weddings and birthday parties, at political events, and even at the airports. Whether it is a trio of guitars, a group of folkloric dancers, or a full mariachi band, the Mexican folk music tradition is part of the Tex-Mex cultural blend. The same holds true in New Mexico, Arizona, and California. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6