ISO/IEC JTC1 SC2 Working Group 2 and UTC FROM: Deborah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N2945

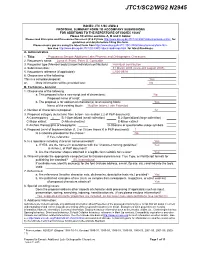

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2945 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Proposal to Encode Additional Latin Phonetic and Orthographic Characters 2. Requester's name: Lorna A. Priest, Peter G. Constable 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual contribution 4. Submission date: 31 March 2005 (revised 9 August 2005) 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): L2/05-097R 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes or, More information will be provided later: No B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): No Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Modifier letters, Latin Extended 2. Number of characters in proposal: 12 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary x B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3094 L2/06-133

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3094 L2/06-133 2006-04-16 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Discussion of the Mayanist Latin letter CUATRILLO WITH COMMA Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2006-04-16 On the Unicore discussion list, Karl Pentzlin asked: “Why do the LATIN capital/small CUATRILLO WITH COMMA need their own codepoints, instead of using LATIN capital/small CUATRILLO + U+0326 COMBINING COMMA BELOW?” The mark does not behave like a combining comma below. First note that real G and real g (not the cuatrillo) are found with U+0327 COMBINING CEDILLA in Latvian orthography, where the cedilla is conventionally drawn with a comma-shape. But with the lower-case g it is not drawn underneath the g, but rather is turned and drawn above it. This is an aside, but it’s just something to note. Second, note that in Figures 18 and 19 of N3082 the true cedilla is drawn with a comma-like shape. This is sort of “typographic handwriting”, though since neither of those two samples shows the CUATRILLO WITH COMMA... well, let’s just say there’s room for confusion that would be better avoided. Third, see Figure 20 of N3082, where a glyph variant of CUATRILLO WITH COMMA is shown with a horizontal bar rather than with a comma. If encoded as a unique character, font designers can more easily make the choice to draw it this way; it’s not at all reasonable to expect COMBINING COMMA BELOW to render in this fashion. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Lilypond Music Glossary

LilyPond The music typesetter Music Glossary The LilyPond development team ☛ ✟ This glossary provides definitions and translations of musical terms used in the documentation manuals for LilyPond version 2.21.82. ✡ ✠ ☛ ✟ For more information about how this manual fits with the other documentation, or to read this manual in other formats, see Section “Manuals” in General Information. If you are missing any manuals, the complete documentation can be found at http://lilypond.org/. ✡ ✠ Copyright ⃝c 1999–2020 by the authors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For LilyPond version 2.21.82 1 1 Musical terms A-Z Languages in this order. • UK - British English (where it differs from American English) • ES - Spanish • I - Italian • F - French • D - German • NL - Dutch • DK - Danish • S - Swedish • FI - Finnish 1.1 A • ES: la • I: la • F: la • D: A, a • NL: a • DK: a • S: a • FI: A, a See also Chapter 3 [Pitch names], page 87. 1.2 a due ES: a dos, I: a due, F: `adeux, D: ?, NL: ?, DK: ?, S: ?, FI: kahdelle. Abbreviated a2 or a 2. In orchestral scores, a due indicates that: 1. A single part notated on a single staff that normally carries parts for two players (e.g. first and second oboes) is to be played by both players. -

Pruebas De Ingreso a Grado Medio

CONSERVATORIO PROFESIONAL DE MÚSICA “PINTOR PINAZO” DE GODELLA PRUEBAS DE ACCESO 2014 Listados de obras orientativas, contenidos mínimos y criterios de evaluación. CONSERVATORIO PROFESIONAL DE MÚSICA “PINTOR PINAZO” DE GODELLA Plaça Santa Magdalena Sofia, 3-D 46110 – GODELLA (Valencia) CONSERVATORI Tel. 963900787 DE GODELLA Correo: [email protected] ÍNDICE - LENGUAJE MUSICAL (1º-3º) 3 - ARMONÍA (4º, 5º) 10 - ANÁLISIS (6º) 12 - HISTORIA DE LA MÚSICA (6º) 14 - ACOMPAÑAMIENTO (6º) 16 - CLARINETE (1º-6º) 18 - SAXOFÓN (1º-6º) 32 - FLAUTA (1º-6º) 45 - FAGOT (1º-6º) 63 - OBOE (1º-6º) 79 - TROMPETA (1º-6º) 93 - TROMPA (1º-6º) 105 - TROMBÓN(1º-6º) 118 - TUBA (1º-6º) 131 - PERCUSIÓN (1º-6º) 144 - VIOLÍN (1º-6º) 167 - VIOLA (1º-6º) 180 - VIOLONCHELO (1º-6º) 192 - CONTRABAJO (1º-6º) 204 - GUITARRA (1º-6º) 217 - PIANO (1º-6º) 241 - PIANO COMPLEMENTARIO (3º-5º) 260 2 CONSERVATORIO PROFESIONAL DE MÚSICA “PINTOR PINAZO” DE GODELLA Plaça Santa Magdalena Sofia, 3-D 46110 – GODELLA (Valencia) CONSERVATORI Tel. 963900787 DE GODELLA Correo: [email protected] PRUEBAS DE ACCESO A LAS ENSEÑANZAS PROFESIONALES PRUEBA B: LENGUAJE MUSICAL CURSO: 1º TODAS LAS ESPECIALIDADES 1. SOLFEO REPENTIZADO Interpretación de un fragmento musical de una extensión no superior a 16 compases con las siguientes características: Claves de Sol o de Fa en 4ª línea. Ámbito vocal del Sol2 al Sol4. Compases de 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 y 6/8, 9/8 ó 12/8. Figuras hasta la semicorchea y su silencio. Puntillos en la blanca, negra y corchea. Ligaduras de prolongación. Grupos de valoración irregular: dosillo y tresillo equivalentes a la unidad de tiempo o de subdivisión. -

Los Estudios Ortogra&Ficos De Nebrija Y Su Influencia

LOS ESTUDIOS ORTOGRA&FICOS DE NEBRIJA Y SU INFLUENCIA SOBRE EL ESTUDIO DE LOS IDIOMAS INDIGENAS EN AMERICA POR ROSA HELENA CHINCHILLA University of Connecticut at Storrs De vi ac potestate litteratum (Salamanca, 1503: 1981) y Reglas de la ortografia castellana(AlcalA de Henares, 1517: 1977) por Antonio de Nebrija forman la base tebrica para el estudio de la ortografia en la epoca colonial. Los misioneros dedicados al aprendizaje de idiomas indigenas se inspiraron y guiaron por la obra de Nebrija Introductiones latinae que contenia distintas versiones de los tratados ortograficos. En el Reino de Guatemala los idiomas quiche, cakchiquel y tzutuhil fueron los mAs detalladamente estudiados en la epoca colonial. Arte de las tres lenguas kaqchiquel, k 'ich y tz 'utuhil (MS c. 1711:1993) por Fr. Francisco Ximdnez, O.P. y Arte de la lengua metropolytana del reino cakchiquel o Cuatimalico (Guatemala: Sebastian Arabalo, 1753) por Fray Ildefonso Jose Flores documentan las distintas controversias que surgieron airededor de la ortografia de los idiomas desconocidos de America y que en el siglo XVIII se estudiaban cientificamente. Estas gramaticas coloniales ejemplifican el problema de utilizar normas europeas para entender la multiplicidad linguistica de America. La atencion cuidadosa dedicada a aspectos de ortografla de las lenguas indigenas por autores coloniales de gramAticas se vincula la obra retbrica de Quintiliano difundida por Nebrija en el siglo XVI. El estudio de los idiomas maya-quiche en el Reino de Guatemala se inici6 con los primeros misioneros franciscanos y dominicos que liegaron a catequizar a los pueblos de Guatemala despuds de 1524. La imprenta en Mexico, y luego en Guate- mala, traj o consigo la posibilidad de imprimir gramAticas para uso de misioneros no iniciados en estas lenguas. -

CURRENT TRENDS in MAYAN LITERACY Joseph Dechicchis Kwansei Gakuin University, Sanda, Japan

CURRENT TRENDS IN MAYAN LITERACY Joseph DeChicchis Kwansei Gakuin University, Sanda, Japan Abstract: The Maya are not dead, and their languages continue to be used. Reviewing the history of Mayan literacy, we focus on several important changes which have been facilitated by an invigorated spirit of pan-Mayanism since the mid-1980s. The Maya have succeeded in changing Guatemalan language policy and statutory law during the past generation. Key legal changes and policy decisions, which seemed perhaps insufficient at first, have resulted in increased literacy, including multimodal literacy, throughout the Mayan areas of Guatemala. Robust language communities, such as the K’iche’ and the Q’eqchi', have certainly benefi tted from government literacy initiatives, but even endangered communities, such as the Ch’orti’, have seen improvements in literacy. Guatemala clearly deserves most of the credit for initiating the new laws and policy changes which have fostered growing literacy among the Mayans. The spirit of pan- Mayanism has also helped to improve Mayan literacy in Belize and Mexico. Guatemala’s initiatives have also been a catalyst for NGO literacy programs, and they have served as a touchstone for pan-Mayan coöperation and coördination in general. Of course, the Maya’s ancient writing is legend, so today’s Mayan literacy is actually a recovery of literacy. Still, on balance, the past 25 years represent perhaps the most optimistic period for Mayan literacy since the destruction of the indigenous Mayan literature in 1697. Key words: Mayan languages, language policy, pan-Mayanism, literacy revitalization MAYAN LANGUAGES AND HISTORICAL MAYAN LITERACY Mayan is a Mesoamerican language family, characteristic of the Maya people. -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3028 L2/06-028

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3028 L2/06-028 2006-01-30 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to add Mayanist Latin letters to the UCS Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2006-01-30 1. Background. In N2931, Lorna Priest and Peter Constable proposed the addition of Ó LATIN LETTER TRESILLO and Ô LATIN LETTER CUATRILLO to the UCS in support of archaic letters used in 16th-century Guatemala to write Mayan languages such as Cakchiquel, Quiché, and Tzutuhil. Although these two letters were accepted for ballotting in PDAM3 of ISO/IEC 10646, as a set of characters they are inadequate to represent texts in normalized 16th-century orthography which use these letters. Such normalization may be rare—it certainly has been in the past—but it should nevertheless be supported by the UCS. The letters in question were devised by Brother Francisco de la Parra (†1560 in Guatemala) and were used by a number of early linguist-missionaries to represent sounds occurring in Cakchiquel, Quiché, and Tzutuhil. In his edition of the Annals of the Cakchiquels, Brinton 1885 gives a set of four letters (one of which is used as a digraph with h) with the following glyphs, alongside descriptions which he attributes to the grammarian Torresano: Ó TRESILLO represented “the only true guttural in the language, being pronounced forcibly from the throat, with a trilling sound (castañeteando)”. This is now described as [q’], the glottalized uvular stop. -

ISO/IEC International Standard 10646-1

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3658 Proposed Draft Amendment (PDAM) 8 ISO/IEC 10646:2003/Amd.8:2009 (E) Information technology — Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) — AMENDMENT 8: Additional symbols, Bamum supplement, CJK Unified Ideographs Extension D, and other characters Page 2, Clause 3, Normative references Replace the list describing the fields of the linked con- tent (CJKU_SR.txt) and the following paragraph with Update the reference to the Unicode Bidirectional Algo- the following text: rithm and the Unicode Normalization Forms as follows: st • 1 field: BMP or SIP code point (0hhhh), Unicode Standard Annex, UAX#9, The Unicode Bidi- (2hhhh) rectional Algorithm: • 2nd field: Radical Stroke index http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/tr9-21.html. (d{1,3}’.d{1,2}), (Radical is one to three di- gits, optionally followed by an apostrophe for alter- Unicode Standard Annex, UAX#15, Unicode Normali- nate radical, followed by a full stop, and ending by zation Forms: one or two digits for the stroke count). http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr15/tr15-31.html. rd • 3 field: Hanzi G sources(G0-hhhh), (G1- hhhh), (G3-hhhh), (G5-hhhh), (G7- Editor’s Note: The versions for the Unicode Standard hhhh), (GS-hhhh), (G8-hhhh), (G9- Annexes mentioned above will be updated as appropri- hhhh), (GE-hhhh), (G_4K), (G_BK), ate in future phases of this amendment process. (G_BKddddd), (G_CH), (G_CY), (G_CYYddddd), (G_CHddddd), (G_FZ), Page 21, Sub-clause 23.1 Source references (G_FZddddd), (G_GHddddd), for CJK Unified Ideographs (G_GFHZBddd), (G_GJZddddd), (G_HC), -

Doulos SIL Font 2006-01-31 Page 1 of 27

Doulos SIL Font 2006-01-31 Page 1 of 27 Doulos SIL Font NRSI staff, SIL Non-Roman Script Initiative (NRSI) 2006-01-31 Note Updates to this font and the documentation are available online at: http://scripts.sil.org/DoulosSILfont. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction to the Doulos SIL Font Package...................................................................................2 Overview of the Doulos SIL Font .......................................................................................................2 Documentation ...........................................................................................................................................3 System requirements..........................................................................................................................3 Features of the font.............................................................................................................................3 Samples ...............................................................................................................................................4 Supported character ranges ..............................................................................................................4 Private-use (PUA) characters.............................................................................................................5 Advanced typographic