Maya Daykeeping: Three Calendars from Highland Guatemala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAYA GLYPHS – Book 2

Maya Numbers & TTTheThe Maya Calendar A Non-Technical Introduction to MAYA GLYPHS – Book 2 by Mark Pitts Maya Numbers and Maya Calendar by Mark Pitts © Mark Pitts 2009 This book is dedicated to the Maya people living today in Mesoamerica. Title Page: A Maya glyph signifying10 periods of about 20 years each, or about 200 years. From Palenque, Mexico. 2 Book 22:::: Maya Numbers & TTTheThe Maya Calendar A Non-Technical Introduction to MAYA GLYPHS Table of Contents 3 Book 2: Maya Numbers and the Maya Calendar CHAPTER 1 – WRITING NUMBERS WITH BARS AND DOTS • The Basics: The Number Zero and Base 20 • Numbers Greater Than 19 • Numbers Greater Than 399 • Numbers Greater Than 7999 CHAPTER 2 - WRITING NUMBERS WITH GLYPHS • Maya Head Glyphs • The Number 20 CHAPTER 3 – THE SACRED AND CIVIL CALENDAR OF THE MAYA • Overview of the Maya Calendar • An Example • The Sacred Calendar and Sacred Year (Tzolk’in) • The Civil Calendar and Civil Year (Haab) • The Calendar Round CHAPTER 4 - COUNTING TIME THROUGH THE AGES • The Long Count • How to Write a Date in Maya Glyphs • Reading Maya Dates • The Lords of the Night • Time and The Moon • Putting It All Together Appendix 1 – Special Days in the Sacred Year Appendix 2 – Maya Dates for 2004 4 Appendix 3 – Haab Patrons for Introductory Glyphs Resources Online Bibliography Sources of Illustrations Endnotes 5 Chapter 111.1. Writing Numbers wwwithwithithith Bars and Dots A Maya glyph from Copán that denotes 15 periods of about 20 years each, or about 300 years. 6 THE BASICS: THE NUMBER ZERO AND BASE 20 The ancient Maya created a civilization that was outstanding in many ways. -

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

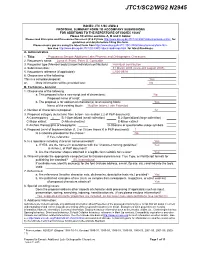

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N2945

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2945 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Proposal to Encode Additional Latin Phonetic and Orthographic Characters 2. Requester's name: Lorna A. Priest, Peter G. Constable 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual contribution 4. Submission date: 31 March 2005 (revised 9 August 2005) 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): L2/05-097R 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes or, More information will be provided later: No B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): No Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Modifier letters, Latin Extended 2. Number of characters in proposal: 12 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary x B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

Winter 2013 Newsletter

WINTER 2013 - No. 8 Chican@ Studies Department University of California, Santa Barbara 93106-4120 - 1713 South Hall Phone: (805) 893-8880 Fax: (805) 893-4076 www.chicst.ucsb.edu www.facebook.com/Chicana.o.Studies Libros, Libros, y Más Libros: Chicana and Chicano Studies in Action Cold as Editorial by Aída Hurtado Estimados Colegas, and Chicano Studies in San Antonio, Texas. ICE ! With every edition of the Chicana and Chicano It is difficult to believe that Studies Department the discipline of Chicana and e-newsletter, one can’t Chicano Studies is in decline help but feel the pos- when so many individuals sibility and magic of the manifest the vibrancy of discipline of Chicana the field in so many arenas. and Chicano Studies. It is important to remind The winter edition of ourselves that the field the e-newsletter is no emerged out of struggle and exception. You will be Aída Hurtado was created by visionaries. delighted as you read Tireless intellectuals and so- each of the articles and amazed by our cial justice seekers who did not know accomplishments as a field. From the the discipline’s trajectory but had an interview with Professor Gerardo Al- unshakeable belief in the power of dana, who had a national and interna- people to learn about themselves tional presence in scholarly and media when institutions of higher learning made them invisible. The discipline of “The books produced by these Chicana and Chicano Studies was cre- extraordinary and gifted women ated from this subterranean knowl- are small miracles that few edge with few resources and a lot of would have predicted and that dedication and corazón. -

Maya Civilisation Information Pack

Maya Everyday Life Information Sheet What would you like to find out about the everyday life of the ancient Maya? Suggested areas to focus on: homes, clothes, food, jobs or industry, role of women, particular practices or traditions, children, farming, crafts. Here are some questions to get you thinking. Did the Maya have special foods for special occasions? What tools did Maya farmers use? What kind of jewellery did ordinary people wear? Did Mayan children go to school? What kind of clothes did people wear? Did the Maya get married? Ensure that your questions cover a range of everyday life themes and enable your answers to show your historical understanding of the civilisation. They should be full of detail. For example, if your question was ‘What kind of houses did people live in?’ your answer could cover the size, the materials used, how they were decorated and what the Maya might have used for windows and doors. Research and Information Gathering: Start here: BBC Teach—Introducing the Maya Civilisation Then move on to these websites, ensuring that you take careful notes: BBC Teach—Jobs in Maya Civilisation—there are also a further 4 clips linked to this series: houses, fashion, food and inventions. They can be accessed towards the bottom of this webpage. Maya Daily Life Maya Fashion and Clothing Ancient Maya Clothing Clothing, Material and Jewellery Farming and Food Murals that give evidence of daily life Mayan Housing It would be a great idea to keep some notes, as you might need the information on later trails. A brief summary: A writing frame for Lewis Group, if required. -

ISO/IEC JTC1 SC2 Working Group 2 and UTC FROM: Deborah

TO: ISO/IEC JTC1 SC2 Working Group 2 and UTC FROM: Deborah Anderson, UC Berkeley DATE: 8 April 2006 RE: Expert Input on “Proposal to add Mayanist Latin letters to the UCS” N3028 (=L2/06-028) Executive Summary: This document provides feedback received on the evidence for uppercase tresillo and cuatrillo and whether these characters are should be included in Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646. The initial query went out over the email list LinguistList. A number of experts were sent email queries separately. There were nine responses, included below. Evidence for Attestation Michael Dürr (#1) and Thomas Larsen (#2) both checked the sources available to them (including manuscripts, facsimile editions, and printed books) and have found that the uppercase forms do occur, albeit rarely and not consistently. As noted by Larsen (#2), uppercase—which is a lowercase modified in various ways—appears at the beginning of paragraphs in the Annals of the Cakchiquels, in handwritten dictionary entries in Calepino en Lengua Cakchiquel, and for cited words in Compendio de Nombres en Lengua Cakchiquel. (Campbell [#3] also mentions attempts at printing case distinctions.) Reasons to Encode (or Not) in the UCS In spite of the inconsistency in their use, most respondents were in support of including these characters in the UCS for the following reasons: • Though the original texts do not use uppercase in the conventional way (i.e., at the beginning of sentences, etc.), the characters’ inclusion would make it possible to print the original text accurately (Maxwell #4, -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3094 L2/06-133

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3094 L2/06-133 2006-04-16 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Discussion of the Mayanist Latin letter CUATRILLO WITH COMMA Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2006-04-16 On the Unicore discussion list, Karl Pentzlin asked: “Why do the LATIN capital/small CUATRILLO WITH COMMA need their own codepoints, instead of using LATIN capital/small CUATRILLO + U+0326 COMBINING COMMA BELOW?” The mark does not behave like a combining comma below. First note that real G and real g (not the cuatrillo) are found with U+0327 COMBINING CEDILLA in Latvian orthography, where the cedilla is conventionally drawn with a comma-shape. But with the lower-case g it is not drawn underneath the g, but rather is turned and drawn above it. This is an aside, but it’s just something to note. Second, note that in Figures 18 and 19 of N3082 the true cedilla is drawn with a comma-like shape. This is sort of “typographic handwriting”, though since neither of those two samples shows the CUATRILLO WITH COMMA... well, let’s just say there’s room for confusion that would be better avoided. Third, see Figure 20 of N3082, where a glyph variant of CUATRILLO WITH COMMA is shown with a horizontal bar rather than with a comma. If encoded as a unique character, font designers can more easily make the choice to draw it this way; it’s not at all reasonable to expect COMBINING COMMA BELOW to render in this fashion. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

The Mayan Astronomy and Calendar Xuan Liang

Duke Summer Program The Mayan Astronomy and Calendar Xuan Liang Math of Universe Paper 2 July 25, 2017 Introduction Before 2012, there was a well-known rumor stated that according to the prediction of the Mayan, all the world would come to the end on December 21th, 2012. When talking about it, we can definitely guarantee that this saying was untrue since sun still rose on the morning of December 22th. However, what we can research more deeply is the origin of this rumor. At least, we can obtain many information about “the end of the world” on the internet and books published before 2012. Is it just a coincidence, or a lie fabricated by charlatans and mystics? How did this rumor relate to Mayan? All of the question can be solved by the Mayan calendar. Maya Civilization The Maya are an indigenous people of Mexico and Central America who have continuously inhabited the lands comprising modern-day Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Campeche, Tabasco, and Chiapas in Mexico and southward through Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. The designation Maya comes from the ancient Yucatan city of Mayapan, the last capital of a Mayan Kingdom in the Post-Classic Period. The Maya people refer to themselves by ethnicity and language bonds such as Quiche in the south or Yucatec in the north (though there are many others). The `Mysterious Maya’ have intrigued the world since their `discovery’ in the 1840's by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood but, in reality, much of the culture is not that mysterious when understood. -

Lilypond Music Glossary

LilyPond The music typesetter Music Glossary The LilyPond development team ☛ ✟ This glossary provides definitions and translations of musical terms used in the documentation manuals for LilyPond version 2.21.82. ✡ ✠ ☛ ✟ For more information about how this manual fits with the other documentation, or to read this manual in other formats, see Section “Manuals” in General Information. If you are missing any manuals, the complete documentation can be found at http://lilypond.org/. ✡ ✠ Copyright ⃝c 1999–2020 by the authors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For LilyPond version 2.21.82 1 1 Musical terms A-Z Languages in this order. • UK - British English (where it differs from American English) • ES - Spanish • I - Italian • F - French • D - German • NL - Dutch • DK - Danish • S - Swedish • FI - Finnish 1.1 A • ES: la • I: la • F: la • D: A, a • NL: a • DK: a • S: a • FI: A, a See also Chapter 3 [Pitch names], page 87. 1.2 a due ES: a dos, I: a due, F: `adeux, D: ?, NL: ?, DK: ?, S: ?, FI: kahdelle. Abbreviated a2 or a 2. In orchestral scores, a due indicates that: 1. A single part notated on a single staff that normally carries parts for two players (e.g. first and second oboes) is to be played by both players.