David Burkhart Oral History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Melody Baggech, Fruit Bag, Babel, Credo for Plastical Score, Etc

Melody Baggech 2100 Fullview Drive, Ada, Oklahoma 74820 | (580) 235-5822 | [email protected] TEACHING EXPERIENCE Professor of Voice – East Central University, 2018-present Private Studio Voice, Music Theatre Voice, Opera Workshop, Diction I and II, Vocal Pedagogy, Music Appreciation, Beginning Italian. Actively recruit and perform. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Associate Professor of Voice - East Central University, 2010-2018 Private Studio Voice, Music Theatre Voice, Opera/Musical Theatre Workshop, Diction I and II, Vocal Pedagogy, Music Appreciation, Beginning Italian. Actively recruit and perform. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Assistant Professor of Voice - East Central University, 2001-2010 Private Studio Voice, Opera Theatre, Diction, Vocal Literature, Beginning Italian, Gospel Singers. Actively recruit and perform. Expanded existing opera program to include full-length performances and collaboration with ECU’s Theatre Department, local theatre companies and professional regional opera company. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Faculty, StartTalk Russian Language Camp, ECU 2012. Subjects taught: Russian folk song, Russian opera, Russian art song/poetry Adjunct Instructor of Voice, Panhandle State University, 1991-1993 Taught private studio voice, accompanied student juries. Performed in faculty recital series. Instructor of Voice, University of Oklahoma, March 20-April 27, 2000 Taught private studio voice to majors and non-majors. Private Studio Voice, Suburban Washington D.C., 2000-2001 Graduate Teaching Assistant, West Texas A&M University, 1988-1990 Voice Instructor, Moore High School, Moore, Oklahoma, 1998-1999 Voice Instructor, Travis Middle School, Amarillo, Texas, 1990-1991 EDUCATION DMA Vocal Performance, University of Oklahoma, 1998 Dissertation – An English Translation of Olivier Messiaen’s Traité de Rythme, de Couleur, et d’Ornithologie vol. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

Kidsbook © Is a Publication of the Negaunee Music Institute

KIDS�OOK CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CSO SCHOOL CONCERTS May 4, 2018, 10:15 and 12:00 CSO FAMILY MATINEE SERIES May 5, 2018, 11:00 and 12:45 TheThe FirebirdFirebird 312-294-3000 | CSO.ORG | 220 S. MICHIGAN AVE. | CHICAGO THE FIREBIRD PERFORMERS Members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Tania Miller conductor Joffrey Academy Trainees and Studio Company guest dancers WHAT WOULD IT �E LIKE TO LIVE PROGRAM INCLUDES SELECTIONS FROM IN A WORLD WITHOUT HARMONY? Glière Russian Sailors’ Dance This program explores the ways from The Red Poppy that dynamic orchestral music and Prokofiev exquisite ballet dancing convey Suite No. 2 from emotion and tell stories of conflict Romeo and Juliet, and harmony. Our concert features Op. 64B Stravinsky’s Suite from The Firebird Tchaikovsky which depicts the heroic efforts of Swan Lake, Op. 20 Prince Ivan and a magical glowing Stravinsky bird struggling to defeat evil and Suite from The Firebird (1919) restore peace to the world. 2 CSO School Concerts / CSO Family Matinee series / THE FIREBIRD CONFLICT &HARMONY Each piece on our program communicates a unique combination of conflict and harmony. The first piece on the concert is Russian Sailor’s Dance from the ballet The Red Poppy by Reinhold Glière [say, Glee-AIR]. What kind of emotion do you feel as the low strings and brass begin the piece? William Shakespeare’s What emotion do you feel as the story of Romeo and Juliet is music gets faster? Would you say filled with conflict, and composer this piece is mostly about harmony Sergei Prokofiev [say: pro-CO-fee- or conflict? Why? What story of ] brilliantly captures this emotion do you imagine the music is in his ballet based on this timeless telling you? tale. -

Mouthpiece Vol. 22 Issue 4

DecemberThe Journal2020 of the Australian Mouthpiece Trumpet Guild Pty Ltd ABN Volume76 085 24022 Issue 446 4 Mouthpiece gets a new look in 2021 Page 17 Interview with “Mr. Clean” — James Wilt of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Page 15 ITG News Page 8 ...and more! Next issue Orchestra matters, (Aussie trumpets of the Aukland Phil); Cornet Coirner International corner, December 2020 1 Volume 22 Issue 4 December 2020 Mouthpiece Volume 22 Issue 4 CONTENTS Click the page number to go to the page Publishing information Page 2 Guild Notes, Editorial, Page 3 Australian Trumpet News Page 4 A Blast from the past Page 7 ITG News Page 8 Orchestra matters (held over to 2021) Page 10 New work review Page 12 Cornet Corner Page 13 International Corner Page 15 Mouthpiece gets a new cover! Page 19 Snippets Page 20 PUBLISHING INFORMATION ADVERTISING RATES Deadlines for 2020 publications: 1 issue 4 issues Issue 1 February 15 (March issue) Issue 2 May 15 (June issue) Full page $100 $340 Issue 3 August 15 (September issue) 1/2 page $55 $180 Issue 4 November 15 (December issue) PLEASE NOTE: The above dates are firm. We need copy 1/4 Page $30 $100 within these time frames for efficient production of 1/8 page) $15 $55 Mouthpiece. Provide copy of adverts and articles via email . JPEG versions Classifieds(4 lines max.) $5 $15 preferred. Enquiries to: Australian Trumpet Guild Pty Ltd P.O. Box 1073 Wahroonga Sponsorships are also available. Contact the ATG NSW 2076 Ph: (02) 9489-6940 for details of packages including advertising, email: [email protected] conference stands and other benefits. -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

Robin Sutherland Oral History

Robin Sutherland Oral History San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives 50 Oak Street San Francisco, CA 94102 Interview conducted January 29 and February 29, 2016 Tessa Updike, Interviewer San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives Oral History Project The Conservatory’s Oral History Project has the goal of seeking out and collecting memories of historical significance to the Conservatory through recorded interviews with members of the Conservatory's community, which will then be preserved, transcribed, and made available to the public. Among the narrators will be former administrators, faculty members, trustees, alumni, and family of former Conservatory luminaries. Through this diverse group, we will explore the growth and expansion of the Conservatory, including its departments, organization, finances and curriculum. We will capture personal memories before they are lost, fill in gaps in our understanding of the Conservatory's history, and will uncover how the Conservatory helped to shape San Francisco's musical culture through the past century. Robin Sutherland Interview This interview was conducted at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music on January 29 and February 29, 2016 in the Conservatory’s archives by Tessa Updike. Tessa Updike Tessa Updike is the archivist for the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Tessa holds a B.A. in visual arts and has her Masters in Library and Information Science with a concentration in Archives Management from Simmons College in Boston. Previously she has worked for the Harvard University Botany Libraries and Archives and the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Use and Permissions This manuscript is made available for research purposes. -

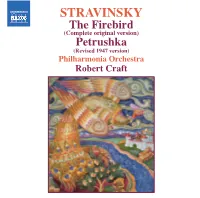

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire. -

El Lenguaje Musical De Luciano Berio Por Juan María Solare

El lenguaje musical de Luciano Berio por Juan María Solare ( [email protected] ) El compositor italiano Luciano Berio (nacido en Oneglia el 24 de octubre de 1925, muerto en Roma el 27 de mayo del 2003) es uno de los más imaginativos exponentes de su generación. Durante los años '50 y '60 fue uno de los máximos representantes de la vanguardia oficial europea, junto a su compatriota Luigi Nono, al alemán Karlheinz Stockhausen y al francés Pierre Boulez. Si lograron sobresalir es porque por encima de su necesidad de novedad siempre estuvo la fuerza expresiva. Gran parte de las obras de Berio ha surgido de una concepción estructuralista de la música, entendida como un lenguaje de gestos sonoros; es decir, de gestos cuyo material es el sonido. (Con "estructuralismo" me refiero aquí a una actitud intelectual que desconfía de aquellos resultados artísticos que no estén respaldados por una estructura justificable en términos de algún sistema.) Los intereses artísticos de Berio se concentran en seis campos de atención: diversas lingüísticas, los medios electroacústicos, la voz humana, el virtuosismo solista, cierta crítica social y la adaptación de obras ajenas. Debido a su interés en la lingüística, Berio ha examinado musicalmente diversos tipos de lenguaje: 1) Lenguajes verbales (como el italiano, el español o el inglés), en varias de sus numerosas obras vocales; 2) Lenguajes de la comunicación no verbal, en obras para solistas (ya sean cantantes, instrumentistas, actores o mimos); 3) Lenguajes musicales históricos, como -por ejemplo- el género tradicional del Concierto, típico del siglo XIX; 4) Lenguajes de las convenciones y rituales del teatro; 5) Lenguajes de sus propias obras anteriores: la "Sequenza VI" para viola sola (por ejemplo) fue tomada por Berio tal cual, le agregó un pequeño grupo de cámara, y así surgió "Chemins II". -

Junior Recital: Beth Alice Reichgott, Mezzo-Soprano" (2004)

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-17-2004 Junior Recital: Beth Alice Reichgott, mezzo- soprano Beth Alice Reichgott Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Reichgott, Beth Alice, "Junior Recital: Beth Alice Reichgott, mezzo-soprano" (2004). All Concert & Recital Programs. 3480. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/3480 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. JUNIOR RECITAL BETH ALICE REICHGOTT, mezzo-soprano Sean Cator, piano Assisted by: Leslie Lyons, violoncello and John Rozzoni, baritone HOCKETT FAMILY RECITAL HALL FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2004 7:00PM JUNIOR RECITAL BETH ALICE REICHGOTT, mezzo-soprano Sean Cator, piano Assisted by: Leslie Lyons, violoncello and John Rozzoni, baritone Vaga luna che inargenti Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) Bella Nice, che d' amore Per pieta, bell' idol mio Auf dem Wasser zu singen Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Du bist die Ruh Auf dem Strom Quando men vo Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) from La boheme INTERMISSION Must the winter come so soon? Samuel Barber (1910-1981) from Vanessa Une poupee aux yeux d'email Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) from Les contes d'Hoffmann Ariettes oubliees (1903) Claude Debussy (1862-1918) 2. I1 Pleure dans mon Coeur 3. L'Ombre des Arbres 4. Chevaux de Bois The Plough Boy Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) The trees they grow so high The Ash Grove Oliver Cromwell Baby, It's Cold Outside Frank Loesser (1910-1969) \ I r,' Junior Recital presented in partial fulfillment of a Bachelor's degree in Vocal Performance and Music Education.