Mapping Environmental Services in Guatemala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elaboración De Cartografía Geológica Y Geomorfológica De Cinco Subcuencas De La Parte Alta De La Cuenca Alta Del Río Nahualate

ELABORACIÓN DE CARTOGRAFÍA GEOLÓGICA Y GEOMORFOLÓGICA DE CINCO SUBCUENCAS DE LA PARTE ALTA DE LA CUENCA ALTA DEL RÍO NAHUALATE María Mildred Moncada Vásquez Marzo 16, 2017 ÍNDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ...................................................................................................................................... 6 2. OBJETIVOS .............................................................................................................................................. 7 3. ANTECEDENTES ...................................................................................................................................... 7 4. ENCUADRE TECTÓNICO REGIONAL ........................................................................................................ 9 5. CONTEXTO VOLCÁNICO REGIONAL ......................................................................................................10 6. METODOLOGÍA .....................................................................................................................................12 7. CARTOGRAFÍA GEOLÓGICA ..................................................................................................................16 7.1 Procesos y unidades litológicas asociadas a Calderas Atitlán ......................................................16 7.1.1 Rocas graníticas (Tb - Tbg) ..........................................................................................................16 7.1.2 Toba María Tecún (Tmt) .....................................................................................................20 -

Taller Internacional De Lecciones Aprendidas Del Volcán De Fuego, Y

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized MEMORIAS DEL TALLER INTERNACIONAL Public Disclosure Authorized DE LECCIONES APRENDIDAS DEL VOLCÁN DE FUEGO. GUATEMALA, 17 -19 DE OCTUBRE DE 2018 HOJA DE RUTA PARA FORTALECER LA GESTIÓN Public Disclosure Authorized DEL RIESGO DE DESASTRES VOLCÁNICOS EN EL PAÍS MEMORIAS DEL TALLER INTERNACIONAL DE LECCIONES APRENDIDAS DEL VOLCÁN DE FUEGO. GUATEMALA, 17 -19 DE OCTUBRE DE 2018 HOJA DE RUTA PARA FORTALECER LA GESTIÓN DEL RIESGO DE DESASTRES VOLCÁNICOS EN EL PAÍS El Taller Internacional de Lecciones Aprendidas del Volcán de Fuego, realizado en la ciudad de Guatemala los días 17 al 19 de octubre de 2018, fue organizado y ejecutado conjuntamente entre el Ministerio de Finanzas Públicas (MINFIN), la Secretaría Ejecutiva de la Coordinadora Nacional para la Reducción de Desastres (SE-CONRED), el Instituto Nacional de Sismología, Vulcanología, Meteorología e Hidrología (INSIVUMEH) y la Secretaría de Planificación y Pro- gramación de la Presidencia (SEGEPLAN); y contó con el apoyo técnico y financiero del Banco Mundial a través del Fondo Global para la Reducción de Desastres (GFDRR por sus siglas en inglés). El presente documento ha sido preparado por un equipo de especialistas del Banco Mun- dial liderado por Lizardo Narváez (Especialista Senior en Gestión de Riesgo de Desastres – Gerente del Proyecto), y conformado por Rodrigo Donoso (Especialista en Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres), Osmar Velasco (Especialista Senior en Gestión de Riesgo de Desastres) y Carolina Hoyos (Especialista en Comunicaciones). El Banco Mundial, el Fondo Mundial para la Reducción y Recuperación de Desastres (GF- DRR) y el Gobierno de Guatemala no garantizan la exactitud de la información incluida en esta publicación y no aceptan responsabilidad alguna por cualquier consecuencia derivada del uso o interpretación de la información contenida. -

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1133, V. 1.2, Table 3

Table 3. (following pages). Spreadsheet of volcanoes of the world with eruption type assignments for each volcano. [Columns are as follows: A, Catalog of Active Volcanoes of the World (CAVW) volcano identification number; E, volcano name; F, country in which the volcano resides; H, volcano latitude; I, position north or south of the equator (N, north, S, south); K, volcano longitude; L, position east or west of the Greenwich Meridian (E, east, W, west); M, volcano elevation in meters above mean sea level; N, volcano type as defined in the Smithsonian database (Siebert and Simkin, 2002-9); P, eruption type for eruption source parameter assignment, as described in this document. An Excel spreadsheet of this table accompanies this document.] Volcanoes of the World with ESP, v 1.2.xls AE FHIKLMNP 1 NUMBER NAME LOCATION LATITUDE NS LONGITUDE EW ELEV TYPE ERUPTION TYPE 2 0100-01- West Eifel Volc Field Germany 50.17 N 6.85 E 600 Maars S0 3 0100-02- Chaîne des Puys France 45.775 N 2.97 E 1464 Cinder cones M0 4 0100-03- Olot Volc Field Spain 42.17 N 2.53 E 893 Pyroclastic cones M0 5 0100-04- Calatrava Volc Field Spain 38.87 N 4.02 W 1117 Pyroclastic cones M0 6 0101-001 Larderello Italy 43.25 N 10.87 E 500 Explosion craters S0 7 0101-003 Vulsini Italy 42.60 N 11.93 E 800 Caldera S0 8 0101-004 Alban Hills Italy 41.73 N 12.70 E 949 Caldera S0 9 0101-01= Campi Flegrei Italy 40.827 N 14.139 E 458 Caldera S0 10 0101-02= Vesuvius Italy 40.821 N 14.426 E 1281 Somma volcano S2 11 0101-03= Ischia Italy 40.73 N 13.897 E 789 Complex volcano S0 12 0101-041 -

Bilingual Test New Enlgish Text.Indd

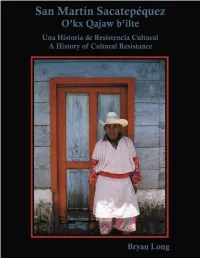

1 2 San Martín Sacatepéquez O’kx Qajaw b’ilte Una Historia de Resistencia Cultural A History of Cultural Resistance 3 Texto: copyright © 2007 Bryan Long Fotografías, gráficas, y mapas: Copyright © 2007 Bryan Long Todo los derechos reservado por autor. Ni un parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducido sin permiso del autor. La presente publicación fue posible por medio del aporte del “Chicago Area Peace Corps Association” (CAPCA) y la Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional (USAID) en Guatemala, a través del fondo para asistencia de proyectos pequeños (SPA) administrado por Cuerpo de Paz Guate- mala. Las opiniones expresadas en este documento son propias del autor y no necesariamente reflejan los puntos de vista de CAPCA, USAID o Cuerpo de Paz. Traducción: Sara Martínez Juan Revisión: Elisa Echeverría, Kathryn Griffin, Danielle Long, Christopher Lutz y Francisco Vásquez Ramírez Text: copyright © 2007 by Bryan Long Photos, graphs, and maps: copyright © 2007 by Bryan Long All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission of the author. The present publication was made possible with support from the Chicago Area Peace Corps Association (CAPCA) and USAID through the Small Project Assistance Fund administered by Peace Corps Guate- mala. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of CAPCA, USAID, or Peace Corps. Translated by: Sara Martínez Juan Edited and/or revised by: Elisa Echeverría, Kathryn Griffin, Danielle -

Oxfam First Published by Oxfam GB in 2000

Risk-Mapping and Local Capacities: Lessons from Mexico and Central America Monica Trujillo Amado Ordonez Rafael Hernandez Oxfam First published by Oxfam GB in 2000 © Oxfam GB 2000 ISBN 0 85598 420 1 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. Reproduction, copy, transmission, or translation of any part of this publication may be made only under the following conditions: • With the prior written permission of the publisher; or • With a licence from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, or from another national licensing agency; or • For quotation in a review of the work; or • Under the terms set out below. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for teaching purposes, but not for resale. Formal permission is required for all such uses, but normally will be granted immediately. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable. Available from the following agents: USA: Stylus Publishing LLC, PO Box 605, Herndon, VA 20172-0605, USA tel: +1 (0)703 661 1581; fax: + 1(0)703 661 1547; email: [email protected] Canada: Fernwood Books Ltd, PO Box 9409, Stn. 'A', Halifax, N.S. B3K 5S3, Canada tel: +1 (0)902 422 3302; fax: +1 (0)902 422 3179; e-mail: [email protected] India: Maya Publishers Pvt Ltd, 113-B, Shapur Jat, New Delhi-110049, India tel: +91 (0)11 649 4850; -

“Los Volcanes En Áreas Protegidas”, Dirigido a Estudiantes Del Instituto Nacional De Educación Básica INEB, De Guazacapán, Santa Rosa

Luis Ernesto Velásquez Contreras Módulo pedagógico “Los Volcanes en Áreas Protegidas”, dirigido a estudiantes del Instituto Nacional de Educación Básica INEB, de Guazacapán, Santa Rosa Asesor: Lic. Guillermo Arnoldo Gaytán Monterroso Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES DEPARTAMENTO DE PEDAGOGÍA Guatemala, mayo de 2011. Este informe fue presentado por el autor como trabajo de Ejercicio Profesional Supervisado EPS, como requisito previo a optar al grado de Licenciado en Pedagogía y Administración Educativa. Guatemala, mayo 2011 ÍNDICE PÁGINA CONTENIDO Introducción i CAPÍTULO I 1 DIAGNÓSTICO 1 1.1. Datos generales de la institución patrocinante 1 1.1.1. Nombre de la institución 1 1.1.2. Tipo de institución 1 1.1.3. Ubicación geográfica 1 1.1.4. Visión 1 1.1.5. Misión 1 1.1.6. Políticas 1 1.1.7. Objetivos 2 1.1.8. Metas 2 1.1.9. Estructura organizacional 3 1.1.10. Recursos humanos, materiales, financieros 4 1.2. Procedimientos, técnicas utilizados 4 1.3. Lista de carencias 4 1.4. Cuadro de análisis de problema 5 1.5. Datos generales de la institución beneficiada 7 1.5.1. Nombre de la Institución 7 1.5.2. Tipo de Institución 7 1.5.3. Ubicación geográfica 7 1.5.4. Visión 7 1.5.5. Misión 7 1.5.6. Políticas 7 1.5.7. Objetivos 7 1.5.8. Metas 7 1.5.9. Estructura Organizacional 8 1.5.10. Recursos humanos, materiales, financieros 8 1.6. Lista de carencias 8 1.7. Cuadro de análisis de problemas 9 1.8. -

Estimaciones De La Población Total Por Municipio. Período 2008-2020

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA Guatemala: Estimaciones de la Población total por municipio. Período 2008-2020. (al 30 de junio) PERIODO Departamento y Municipio 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 REPUBLICA 13,677,815 14,017,057 14,361,666 14,713,763 15,073,375 15,438,384 15,806,675 16,176,133 16,548,168 16,924,190 17,302,084 17,679,735 18,055,025 Guatemala 2,994,047 3,049,601 3,103,685 3,156,284 3,207,587 3,257,616 3,306,397 3,353,951 3,400,264 3,445,320 3,489,142 3,531,754 3,573,179 Guatemala 980,160 984,655 988,150 990,750 992,541 993,552 993,815 994,078 994,341 994,604 994,867 995,130 995,393 Santa Catarina Pinula 80,781 82,976 85,290 87,589 89,876 92,150 94,410 96,656 98,885 101,096 103,288 105,459 107,610 San José Pinula 63,448 65,531 67,730 69,939 72,161 74,395 76,640 78,896 81,161 83,433 85,712 87,997 90,287 San José del Golfo 5,596 5,656 5,721 5,781 5,837 5,889 5,937 5,981 6,021 6,057 6,090 6,118 6,143 Palencia 55,858 56,922 58,046 59,139 60,202 61,237 62,242 63,218 64,164 65,079 65,963 66,817 67,639 Chinuautla 115,843 118,502 121,306 124,064 126,780 129,454 132,084 134,670 137,210 139,701 142,143 144,535 146,876 San Pedro Ayampuc 62,963 65,279 67,728 70,205 72,713 75,251 77,819 80,416 83,041 85,693 88,371 91,074 93,801 Mixco 462,753 469,224 474,421 479,238 483,705 487,830 491,619 495,079 498,211 501,017 503,504 505,679 507,549 San Pedro Sacatepéquez 38,261 39,136 40,059 40,967 41,860 42,740 43,605 44,455 45,291 46,109 46,912 47,698 48,467 San Juan Sacatepéquez 196,422 202,074 208,035 213,975 219,905 -

Geological and Geochemical Reconnaissance of a Non-Volcanic

GRC Transactions, Vol. 38, 2014 Geological and Geochemical Reconnaissance of a Non-Volcanic Geothermal Prospect in Guatemala — Joaquina Geothermal Field R. B. Libbey1,2, A. E. Williams-Jones1, B. L. Melosh1, and N. R. Backeberg1 1McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada 2Adage Ventures Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada Keywords Introduction Geochemistry, soil CO2, shallow temperature, soil chemistry, Regional Geology bulk rock chemistry, fluid inclusions, Motagua, Guatemala, deep-circulation Based on the morphotectonic zones of Burkart and Self (1985), the Joaquina project area is situated in the northern section of Guatemala’s Zone III. This zone is characterized Abstract by monogenetic volcanism related to East-West extension and decompressive generation of relatively mafic, olivine- to neph- The results of a geological and geochemical survey of the Joa- eline-normative magmas. Quaternary, behind-the-volcanic-front quina geothermal field in Guatemala are summarized. Structural (BFV) volcanism has a clear association with Holocene-Mio- mapping, soil chemistry including CO2 (soil gas), and shallow temperature measurements were employed in conjunction with petrographic and bulk rock chemical analyses of drill cutting samples to identify regions of hydrothermal fluid upwelling and outflow in the Joaquina system. A chemical reconnaissance of thermal manifestations provided evidence for the presence of a meteorically-derived Na-bicarbonate(-sulfate) geothermal fluid, similar to those in neighboring geothermal systems in Honduras. Geo- thermometric analyses of the Joaquina fluids yielded reservoir temperature estimates (Tsilica-adiabatic) of ~180°C. Sulphur and carbon isotopic analyses of soil gas and sulfide minerals in drill core indicate that the sulfur, CO2, and CH were likely derived from Figure 1. -

Geothermal Potential of the Cascade and Aleutian Arcs, with Ranking of Individual Volcanic Centers for Their Potential to Host Electricity-Grade Reservoirs

DE-EE0006725 ATLAS Geosciences Inc FY2016, Final Report, Phase I Final Research Performance Report Federal Agency and Organization: DOE EERE – Geothermal Technologies Program Recipient Organization: ATLAS Geosciences Inc DUNS Number: 078451191 Recipient Address: 3372 Skyline View Dr Reno, NV 89509 Award Number: DE-EE0006725 Project Title: Geothermal Potential of the Cascade and Aleutian Arcs, with Ranking of Individual Volcanic Centers for their Potential to Host Electricity-Grade Reservoirs Project Period: 10/1/14 – 10/31/15 Principal Investigator: Lisa Shevenell President [email protected] 775-240-7323 Report Submitted by: Lisa Shevenell Date of Report Submission: October 16, 2015 Reporting Period: September 1, 2014 through October 15, 2015 Report Frequency: Final Report Project Partners: Cumming Geoscience (William Cumming) – cost share partner GEODE (Glenn Melosh) – cost share partner University of Nevada, Reno (Nick Hinz) – cost share partner Western Washington University (Pete Stelling) – cost share partner DOE Project Team: DOE Contracting Officer – Laura Merrick DOE Project Officer – Eric Hass Project Monitor – Laura Garchar Signature_______________________________ Date____10/16/15_______________ *The Prime Recipient certifies that the information provided in this report is accurate and complete as of the date shown. Any errors or omissions discovered/identified at a later date will be duly reported to the funding agency. Page 1 of 152 DE-EE0006725 ATLAS Geosciences Inc FY2016, Final Report, Phase I Geothermal Potential of -

¡El Pacaya Explota!

BUSQUE LOS BATRES SALE CHISMES DE EL LUNES PARA Cuando los EL MUNDIAL GÝ>(- LA SEMANA GÝ>)' rápidos muerden 7*&3/&4%&.":0%&t(6"5&."-"t"¨0t/0 Q2.00 a los grandes EN TODO EL PAÍS Bellezas se SIP 2010 / LIMA divierten en la fiesta de la televisión GÝ>(+ CENTRO URUY S ESCUINTLA INSIVUMEH LAS UG DO : ANTICIPA OTO F POSIBLE ¡EL PACAYA TORMENTA TROPICAL EXPLOTA! GÝ>+ EL GOBIERNO DECLARA ESTADO DE CALAMIDAD PÚBLICA TRASLADO DE REOS A JUZGADOS SIGUE SIN SOLUCIÓN GÝ>, La Máquina de Ideas CONSULTORA INTERNACIONAL DE MEDIOS LAVA Y LLUVIA DE ARENA Y PIEDRAS, EN SAN VICENTE PACAYA, CAUSA LA www.lamaquinadeideas.com QUEMA DE 4 CASAS Y LA EVACUACIÓN DE VECINOS DE 5 COMUNIDADES. GÝ>j)$* BUSCA TAVITO Y SUS BELLAS Cuando los TU SÚPER BAILARINAS VUELVEN GÝ>(. PÁGINA GÝ>(+ A LOS ESCENARIOS rápidos muerden 4#"%0%&.":0%&t(6"5&."-"t"¨0t/0 Q2.00 a los grandes EN TODO EL PAÍS Exija gratis su lámina con SIP 2010 / LIMA las fotografías de su guía coleccionable OCCIDENTE 26&5;"-5&/"/(0t4"/."3$04t)6&)6&5&/"/(0t$)*."-5&/"/(0t40-0-t5050/*$"1/t26*$) OOL Y GUATEMALA O R A V AL : OTO EL PACAYA GOLPEA F A LOS POBRES DOÑA LUCILA ALFARO, DE 78 AÑOS, HA SUFRIDO OTRAS ERUPCIONES, PERO ASEGURA QUE LA DEL JUEVES FUE TAN LARGA QUE PERDIÓ LO POCO QUE TENÍA: SU CASA, ANIMALES Y SIEMBRAS. GÝ>j)$- La Máquina de Ideas 2 MIL 356 60 % CONSULTORA INTERNACIONAL DE MEDIOS PERSONAS VIVIENDAS DEL CAFÉ www.lamaquinadeideas.com EVACUADAS DESTRUIDAS SE PERDERÁ EL HUMOR DE LA EL GORDO LLUVIA DE ARENA DE LA 51348 Cuando los ESTÁ EN LA MATRACA SANTA GÝ>(0 rápidos muerden %0.*/(0%&.":0%&t(6"5&."-"t"¨0t/0 Q2.00 Si se perdió las EN TODO EL PAÍS a los grandes fotografías SIP 2010 / LIMA de la guía coleccionable ¡exíjalas gratis este día! IONAL ES C PE A C N I A N L Ó I C I D E GUATEMALA FOTO: ALVARO YOOL FOTO: ALVARO LOS NÚMEROS OFICIALES TORMENTA 8,737 EVACUADOS 4,342 La Máquina de Ideas EN ALBERGUES CONSULTORA INTERNACIONAL DE MEDIOS MORTAL www.lamaquinadeideas.com LAS LLUVIAS OCASIONADAS POR EL FENÓMENO NATURAL “ÁGATA” 3,475 COBRARON LA VIDA DE 8 PERSONAS Y 16 ESTÁN DESAPARECIDAS. -

(3) Producción De Mapas Geomorfológicos 1) Area De Mapeo

2.3 Mapeo de Amenaza (3) Producción de Mapas Geomorfológicos 1) Area de Mapeo Geomorfológico Se elaboraron los siguientes mapas geomorfológicos a través de la interpretación de fotografías aéreas y estudio de campo. Estos resultados fueron ingresados a mapas digitales de ortofotomapas escala 1:10,000 o mapas topográficos de 1:50,000 (Volcán Tacaná). La escala de salida de los mapas geomorfológicos es de 1:25,000, exceptuando la del área de estudio del Volcán Tacaná. Tabla 2.3.6-2 Escala de los mapas geomorfológicos Ciudades, Areas y Terremotos Volcanes Deslizamientos Inundaciones Cuencas Ciudad de Guatemala 1:25,000 1:25,000 Quetzaltenango 1:25,000 1:25,000 Mazatenango 1:25,000 Escuintla 1:25,000 Puerto Barrios 1:25,000 Tacana 1:50,000 Santiaguito 1:25,000 Cerro Quemado 1:25,000 Pacaya 1:25,000 Antigua Guatemala 1:25,000 Región Nor-Oeste -- Región Central -- Cuenca de Río Samalá 1:25,000 Cuenca de Río Acomé 1:25,000 Cuenca Río Achiguate 1:25,000 Cuenca R. María Linda 1:25,000 Nota: Se elaboró (en datos SIG) un mapa de distribución de deslizamientos para las regions Nor-Oeste y Central. 2) Leyenda del Mapa Geomorfológico La Tabla 2.3.6-3 muestra las leyendas para un mapa geomorfológico. 2-226 2.3 Mapeo de Amenaza Tabla 2.3.6-3 Leyenda de mapas geomorfológicos 2-227 2.3 Mapeo de Amenaza 3) Características geomorfológicas de cada área de estudio a) Ciudad de Guatemala En la Ciudad de Guatemala generalmente prevalece la erosión. La meseta está significativamente diseccionada por valles profundos, y las cabeceras de los valles están siendo cortados más y más hacia la meseta. -

Folleto De Los Volcanes De Guatemala

LOS FOCOS ERUPTIVOS CUATERNARIOS DE GUATEMALA1 Otto H. Bohnenberger Instituto Centroamericano de Investigación y Tecnología Industrial Guatemala RESUMEN Aprovechando los estudios volcanológicos fundamentales de Sapper (1925), Meyer-Abich (1956) Williams (1960) y Williams, McBirney y Dengo (1964), se efectuó un inventario de los focos eruptivos cuaternarios de la República de Guatemala. En este estudio se usaron ventajosamente los modernos mapas topográficos a escala 1:50 000 y fotografías aéreas del Instituto Geográfico Nacional de Gua- temala. Los focos eruptivos se asentaron en forma tabular, registrando número y nombre, características del edificio volcánico, tipo de roca, coordenadas geográficas con aproximación a cinco segundos, coordenadas UTM con aproximación de 100 metros y localización departa- mental. Este estudio, que se considera preliminar, arroja el número de 324 focos eruptivos en Guatemala, la gran mayoría representados por peque- ños conos cineríticos y de lava, en el suroriente del país, pero incluye desde luego los grandes estratovolcanes, conocidos y descritos por muchos investigadores. Sin embargo, cabo mencionar específicamente que en la lista no se incluyeron tres volcanes citados por Sapper (1925): Lacandón, Zunil y Santo Tomás, que se consideran formas erosivas de rocas volcánicas más antiguas. Incluidos están 11 volcanes clasificados como "activos” en el Catálogo de los Volcanes Activos del Mundo (1958, Asociación Vulcanológica Internacional). Tres de éstos: Santiaguito, Fuego y Pacaya, han registrado erupciones en los últimos diez años. ABSTRACT Relying on basic volcanological studis by Sapper (1925), Meyer-Abich (1956) Williams (1960), and Williams, McBirney and Dengo (1964) an inventory of the Quaternary eruptive vents was made in the Republic of Guatemala.