A Palestinian Perspective on the Peace Process Mahdi Abdul Hadi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

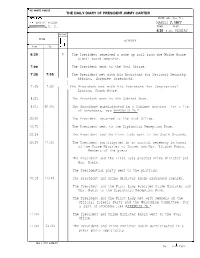

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

7. Politics and Diplomacy

Hoover Press : Zelnick/Israel hzeliu ch7 Mp_119 rev1 page 119 7. Politics and Diplomacy as israeli forces were clearing recalcitrant settlers from their Gaza homes on August 16, 2005, Khalil Shikaki, director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PSR) in Ra- mallah, published a column in the Jerusalem Post headlined, “How Sharon and Abbas Can Both Win.”1 Shikaki, a pollster and political analyst respected in Israel and the west, questioned the wisdom of Israeli unilateralism in Gaza and on the West Bank as opposed to Lebanon, where no one on the other side wanted to talk. Here, he argued, Hamas may be as close-minded as Hez- bollah, preferring to paint Israel’s withdrawal as a victory for Pal- estinian resistance, but Abu Mazen, supported by Palestinian pub- lic opinion, wanted to reduce tensions and negotiate. Make him look good by easing restrictions on Palestinian trade and move- ment, and he will help Sharon and Israel by defeating Hamas and talking about the terms for settling the conflict. In other words, let the PA rather than Hamas control the Palestinian narrative of withdrawal. Shakaki updated his survey data two months later for a con- ference at Brandeis University hosted by Shai Feldman, director of the Crown Center for Middle East Studies and former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies in Tel Aviv. By that October conference, 84 percent of Palestinians were convinced that violence had played a role in the Israeli withdrawal. Irre- 1. Khalil Shikaki, “How Sharon and Abbas Can Both Win,” Jerusalem Post, August 16, 2005. -

The Labor Party and the Peace Camp

The Labor Party and the Peace Camp By Uzi Baram In contemporary Israeli public discourse, the preoccupation with ideology has died down markedly, to the point that even releasing a political platform as part of elections campaigns has become superfluous. Politicians from across the political spectrum are focused on distinguishing themselves from other contenders by labeling themselves and their rivals as right, left and center, while floating around in the air are slogans such as “political left,” social left,” “soft right,” “new right,” and “mainstream right.” Yet what do “left” and “right” mean in Israel, and to what extent do these slogans as well as the political division in today’s Israel correlate with the political traditions of the various parties? Is the Labor Party the obvious and natural heir of The Workers Party of the Land of Israel (Mapai)? Did the historical Mapai under the stewardship of Ben Gurion view itself as a left-wing party? Did Menachem Begin’s Herut Party see itself as a right-wing party? The Zionist Left and the Soviet Union As far-fetched as it may seem in the eyes of today’s onlooker, during the first years after the establishment of the state, the position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union was the litmus test of the left camp, which was then called “the workers’ camp.” This camp viewed the centrist liberal “General Zionists” party, which was identified with European liberal and middle-class beliefs in private property and capitalism, as its chief ideological rival (and with which the heads of major cities such as Tel Aviv and Ramat Gan were affiliated). -

Military Activism and Conservatism During the Intifadas Murat ÜLGÜL* Abstract Introduction

Soldiers and The Use of Force: Military Activism and Conservatism During The Intifadas Murat ÜLGÜL* Abstract Introduction Are soldiers more prone and likely to use force Are soldiers more prone to use force and initiate conflicts than civilians? To bring a and initiate conflicts than civilians? new insight to this question, this article compares The traditional view in the civil- the main arguments of military activism and military relations literature stresses that military conservatism theories on Israeli policies during the First and Second Intifadas. Military professional soldiers are conservative activism argues that soldiers are prone to end in the use of force because soldiers political problems with the use of force mainly are the ones who mainly suffer in war. because of personal and organizational interests Instead, this view says, it is the civilians as well as the effects of a military-mindset. The proponents of military conservatism, on the who initiate wars and conflicts because, other hand, claim that soldiers are conservative without military knowledge, they on the use of force and it is the civilians most underestimate the costs of war while likely offering military measures. Through an overvaluing the benefits of military analysis of qualitative nature, the article finds 1 action. In recent decades, military that soldiers were more conservative in the use of force during the First Intifadas and Oslo conservatism has been challenged by Peace Process while they were more hawkish in a group of scholars who argue that the the Second Intifada. This difference is explained traditional view is based on a limited by enemy conceptions and by the politicization number of cases, mainly civil-military of Israeli officers. -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

Australian Politicians

Asem Judeh Melbourne 19 October 2009 The Hon Arch Bevis MP Chair Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Mr Bevis Supplementary Submission on re-listing Hamas’s Brigades and PIJ As you know the politics of Israel-Palestine issue is always attracting the international community attention and always there are important development day-to-day basis. Because of that I am writing this supplementary submission that summarises the important developments in relation to re-listing the Brigades and PIJ since I submitted my original submission to PJCIS. The recent development supports all the facts, analysis and serious allegations included in my previous submission. These recent facts and reports show clearly the root causes of the violence and terrorism in Palestine. It proves that occupation is violence and terrorism; colonization is violence and terrorism. This new evidence proves that ASIO’s assessment report is politically motivated and misleading the parliament and public. Finally, when I appear before the Committee to give oral evidence, I will present more facts and answer all clarifications and questions from the Committee members. Sincerely yours, Asem Judeh Supplementary Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Review of the re-listing of Hamas' Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades and PIJ Page: 1 of 1 Asem Judeh’s Supplementary Submission on re-listing Hamas’s Brigades and PIJ 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 4 2. UN FACT FINDINGS MISSION ON THE GAZA CONFLICT ................ 4 WHY UN FACT FINDINGS MISSION ON THE GAZA CONFLICT REPORT IS RELATED TO PJCIS INQUIRY? .................................................................................................... 5 ISRAEL AND HAMAS RESPONSE TO UN FACT FINDING MISSION AND UNHR DECISION ENDORSING THE REPORT, OCTOBER 16. -

Israel's Soviet Immigrants

4 ISRAEL’S SOVIET IMMIGRANTS Dr Neill Lochery, Director of the Centre for Israeli Studies at University Israel’s Soviet College London, has been conducting research on the impact of Russian immigrants on contemporary Israeli politics. Below, he considers the degree Immigrants to which they have become assimilated within Israeli society and their influence on the political agenda. HE arrival of Israel’s Soviet immigrants It was within the context of need that the political and economic conditions in Russia and their assimilation into Israeli society first members of this Aliyah were welcomed meant that many Jews decided to remain in Tduring the 1990s is one of the most at Ben-Gurion airport in Tel Aviv in 1988. For the countries of the former Soviet Union important developments in the State of Israel, Yitzhak Shamir, the then Israeli prime (FSU). Unlike previous Aliyahs who generally and for the prospects of finding an accord minister, their arrival was a boost to his cut their ties with their countries of origin, between Israel, the Palestinians and the wider widely declared goal of settling extensively in this group has maintained close ties with the Arab world. Like most aspects of the the West Bank and Gaza Strip in order both to motherland. Many immigrants still have development of Israel the arrival of this new change the demographic balance in these family in the FSU and return for holidays, Aliyah (wave of Jewish immigrants) has areas that heavily favoured the Palestinians, shopping and family events. The ever- brought challenges, problems and unforeseen and to make it extremely difficult for these growing numbers of flights between Tel Aviv, consequences. -

Statistical Information

STATISTICAL INFORMATION VOTES CAST FOR SENATORS IN 2008, 2010, and 2012 [Compiled from official statistics obtained by the Clerk of the House. Figures in the last column, for the 2012 election, may include totals for more candidates than the ones shown.] Vote Total vote State 2008 2010 2012 cast in 2012 Democrat Republican Democrat Republican Democrat Republican Alabama ....................... 752,391 1,305,383 515,619 968,181 .................... .................... .................... Alaska .......................... 1,51,767 147,814 60,045 90,839 .................... .................... .................... Arizona ........................ .................... .................... 592,011 1,005,615 1,036,542 1,104,457 2,243,422 Arkansas ...................... 804,678 .................... 288,156 451,618 .................... .................... .................... California ..................... .................... .................... 5,218,441 4,217,366 7,864,624 4,713,887 12,578,511 Colorado ...................... 1,230,994 990,755 851,590 822,731 .................... .................... .................... Connecticut .................. .................... .................... 605,204 498,341 792,983 604,569 1,511,764 Delaware ...................... 257,539 140,595 174,012 123,053 265,415 115,700 399,606 Florida .......................... .................... .................... 1,092,936 2,645,743 4,523,451 3,458,267 8,189,946 Georgia ........................ 909,923 1,228,033 996,516 1,489,904 ................... -

Interest in Past Leaders Reflects the Crisis on the Israeli Left

Interest in Past Leaders Reflects the Crisis on the Israeli Left by Prof. Hillel Frisch BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 875, June 26, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The crisis of the Israeli left is reflected in the sharply declining interest within Israel in Yitzhak Rabin compared to Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir. The opposite trend is visible abroad. The problem of the left is that it is Israelis who vote, not the world community. A search for the term “Yitzhak Rabin” in Hebrew in Google Trends reveals a sharp decline in interest since 2005, the tenth anniversary of Rabin’s assassination. The decline is precipitous in the years immediately following 2005 and then levels off. Still, the decline over time is substantial. If searches for Rabin in 2004 represent 100, the high point, this figure was down to 6 by October 2017 – less than one-twelfth the number of searches 13 years before. Interest in Rabin is also sharply correlated to the period of commemoration that occurs in November of each year on the anniversary of the assassination. Obviously, official remembrance days heighten awareness in any particular year, but they have done little to arrest the overall decline in interest in Rabin. “Yitzhak Rabin” in Google Trends The same exercise regarding Menachem Begin and Shamir shows a stark contrast. Whereas interest in Rabin has declined sharply, interest in Begin and Shamir remains surprisingly constant – not only over the years, but within the calendar year. These comparisons say nothing about the absolute number of searches over time among the three leaders. They do say something conclusive, however, about trends in interest and therefore in the collective historical memory. -

Experiential Learning: Role-Play

NON-CLASSROOM ENRICHMENT EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING How to Use Role-Play Role-play is a type of simulation that enables participants to step into the shoes of an historical or other figure and gain insight into the world in which they lived. For students or participants, assuming the role of another person allows for evaluating that individual’s ideology and viewpoint in the context of a specific moment in time as learners internalize key concepts. In addition, role-play can shed light on the emotional and psychological aspects of heroism and defeat and the struggles in decision-making at critical junctures. When working with students and assigning them roles, the more information that is learned about the individual’s experiences and views before the role-play commences, the better that person can be represented. Using this technique, participants will have the opportunity to identify with the individual and to make emotional connections with history. How does one facilitate role-play? If working with a group of participants for a role-play session or classroom activity such as a Mock Zionist Congress etc. where the participants will take in part in the role play: 1. First, identify the individuals who played a major role in shaping history in the period being studied. Then, determine sources of information that would inform a role-play (biographies, documents they authored such as diaries, memos or books, documents about them such as newspaper articles or memoirs, photos, etc.) 2. Assign each participant an individual to portray. That participant should research the individual in-depth to determine characteristics, views, experiences that influenced their expertise or opinions, etc. -

A Never-Ending Quest for Peace

THE NEW YORK TIMES, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 A NEVER-ENDING QUEST FOR PEACE Israel has lost a light, the world has lost a forward thinker, the Jewish people have lost a wise voice, and I have lost a friend. - S. DANIEL ABRAHAM SHIMON PERES Z”L AUG. 2, 1923 - SEPT. 28, 2016 Founder of a Nation | Nobel Prize Winner | Humanitarian | Visionary Warrior for Peace | Statesman | Political Giant | Author and Poet An Inspiration for a Generation President Shimon Peres z”l, the last of Israel’s founding tapped him in 1948 to head Israel’s nascent Navy, and then generation and a man who served his country for seven named him director general of Israel’s Ministry of Defense. decades, died Sept. 28, two weeks after suffering a stroke. First elected to Israel’s Knesset in 1959, he held numerous Respected worldwide, he had been honored with a Nobel positions throughout the years, including: president, twice Peace Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom, French Legion of prime minister, acting prime minister, vice premier, deputy Honour and the Congressional Gold Medal. He was 93. prime minister, senior deputy prime minister, foreign minister, defense minister, finance minister and deputy defense minister. Unwavering in his optimism that Israel could achieve peace with its neighbors, he dedicated his life to that pursuit, was He also headed the Labor Party for 15 years, became the first at the forefront of creating Israel’s defense forces and was Israeli president in history to speak to a Muslim country’s instrumental in turning Israel into the startup nation it is legislature when he addressed the Turkish parliament in 2007 today.