Snakebite — Prevention and First Aid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

2008 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Le Centre Sheraton Montréal Hotel Montréal, Quebec, Canada 23 July 2008 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University Biological Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - OE 167 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 31 May 2008 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 23 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Salon A&B in the Le Centre Sheraton, Montréal Hotel. President Mushinsky plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book. Items that a governor wishes to discuss will be exempted from the motion for blanket acceptance and will be acted upon individually. We will cover the proposed consititutional changes following discussion of reports. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Montreal. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Montréal on 20 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive late on the afternoon of 22 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 27 July 2005 from 1800-2000 h in Salon A&C. Please plan to attend the BOG meeting and Annual Business Meeting. I look forward to seeing you in Montréal. Sincerely, Maureen A. Donnelly ASIH Secretary 1 ASIH BOARD OF GOVERNORS 2008 Past Presidents Executive Elected Officers Committee (not on EXEC) Atz, J.W. -

Tan Choo Hock Thesis Submitted in Fulfi

TOXINOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATIONS OF THE VENOM OF HUMP-NOSED PIT VIPER (HYPNALE HYPNALE) TAN CHOO HOCK THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2013 Abstract Hump-nosed pit viper (Hypnale hypnale) is a medically important snake in Sri Lanka and Western Ghats of India. Envenomation by this snake still lacks effective antivenom clinically. The species is also often misidentified, resulting in inappropriate treatment. The median lethal dose (LD50) of H. hypnale venom varies from 0.9 µg/g intravenously to 13.7 µg/g intramuscularly in mice. The venom shows procoagulant, hemorrhagic, necrotic, and various enzymatic activities including those of proteases, phospholipases A2 and L-amino acid oxidases which have been partially purified. The monovalent Malayan pit viper antivenom and Hemato polyvalent antivenom (HPA) from Thailand effectively cross-neutralized the venom’s lethality in vitro (median effective dose, ED50 = 0.89 and 1.52 mg venom/mL antivenom, respectively) and in vivo in mice, besides the procoagulant, hemorrhagic and necrotic effects. HPA also prevented acute kidney injury in mice following experimental envenomation. Therefore, HPA may be beneficial in the treatment of H. hypnale envenomation. H. hypnale-specific antiserum and IgG, produced from immunization in rabbits, effectively neutralized the venom’s lethality and various toxicities, indicating the feasibility to produce an effective specific antivenom with a common immunization regime. On indirect ELISA, the IgG cross-reacted extensively with Asiatic crotalid venoms, particularly that of Calloselasma rhodostoma (73.6%), suggesting that the two phylogenically related snakes share similar venoms antigenic properties. -

Zootaxa, a Taxonomic Revision of the South Asian Hump

Zootaxa 2232: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A taxonomic revision of the South Asian hump-nosed pit vipers (Squamata: Viperidae: Hypnale) KALANA MADUWAGE1,2, ANJANA SILVA2,3, KELUM MANAMENDRA-ARACHCHI2 & ROHAN PETHIYAGODA2,4 1Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka 2Wildlife Heritage Trust, P.O. Box 66, Mt Lavinia, Sri Lanka 3Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University, Saliyapura, Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka 4Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The hump-nosed pit vipers of the genus Hypnale are of substantial medical importance in Sri Lanka and India, being included among the five snakes most frequently associated with life-threatening envenoming in humans. The genus has hitherto been considered to comprise three species: H. hypnale, common to Sri Lanka and the Western Ghats of peninsular India; and H. nepa and H. walli, both of which are endemic to Sri Lanka. The latter two species have frequently been confused in the literature. Here, through a review of all extant name-bearing types in the genus, supplemented by examination of preserved specimens, we show that H. nepa is restricted to the higher elevations of Sri Lanka’s central mountains; that H. walli is a junior synonym of H. nepa; and that the endemic species widely distributed in the island’s south-western ‘wet-zone’ lowlands is H. zara. We also draw attention to a possibly new species known only from a single specimen collected near Galle in southern Sri Lanka. -

Guidelines for the Management of Snake-Bites

Guidelines for the management of snake-bites David A Warrell WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data Warrel, David A. Guidelines for the management of snake-bites 1. Snake Bites – education - epidemiology – prevention and control – therapy. 2. Public Health. 3. Venoms – therapy. 4. Russell's Viper. 5. Guidelines. 6. South-East Asia. 7. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia ISBN 978-92-9022-377-4 (NLM classification: WD 410) © World Health Organization 2010 All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

Presumptive Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Withana et al. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2014, 20:26 http://www.jvat.org/content/20/1/26 CASE REPORT Open Access Presumptive thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura following a hump-nosed viper (Hypnale hypnale) bite: a case report Milinda Withana1, Chaturaka Rodrigo2*, Ariaranee Gnanathasan2 and Lallindra Gooneratne3 Abstract Hump-nosed viper bites are frequent in southern India and Sri Lanka. However, the published literature on this snakebite is limited and its venom composition is not well characterized. In this case, we report a patient with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-like syndrome following envenoming which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported in the literature before. A 55-year-old woman from southern Sri Lanka presented to the local hospital 12 hours after a hump-nosed viper (Hypnale hypnale) bite. Five days later, she developed a syndrome that was characteristic of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with fever, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolysis, renal impairment and neurological dysfunction in the form of confusion and coma. Her clinical syndrome and relevant laboratory parameters improved after she was treated with therapeutic plasma exchange. We compared our observations on this patient with the current literature and concluded that thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is a theoretically plausible yet unreported manifestation of hump-nosed viper bite up to this moment. This study also provides an important message for clinicians to look out for this complication in hump-nosed viper bites since timely treatment can be lifesaving. Keywords: Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Hump-nosed viper, Thrombotic microangiopathy, Snakebite, Hemolytic uremic syndrome Background Since TTP has high mortality without prompt recogni- Hump-nosed vipers of the genus Hypnale have three tion and treatment, awareness about this potential com- species Hypnale hypnale (Figure 1), Hypnale nepa and plication associated with hump-nosed viper envenoming Hypnale zara [1]. -

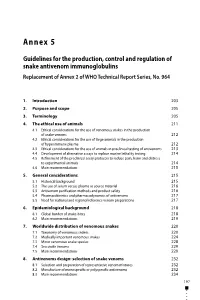

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

DERMAL IRIDOPHORES IN SNAKES; CORRELATIONS WITH HABITAT ADAPTATION AND PHYLOGENY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kleese, William Carl Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 04:07:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289250 INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Acute Myocardial Infarction Associated with Thrombotic Microangiopathy

de Silva et al. Journal of Medical Case Reports (2017) 11:305 DOI 10.1186/s13256-017-1484-z CASEREPORT Open Access Acute myocardial infarction associated with thrombotic microangiopathy following a hump-nosed viper bite: a case report Nipun Lakshitha de Silva1, Lalindra Gooneratne2 and Eranga Wijewickrama1,3* Abstract Background: Hump-nosed viper bite is the commonest cause of venomous snakebite in Sri Lanka. Despite initially being considered a moderately venomous snake more recent reports have revealed that it could cause significant systemic envenoming leading to coagulopathy and acute kidney injury. However, myocardial infarction was not reported except for a single case, which occurred immediately after the snakebite. Case presentation: A 50-year-old previously healthy Sri Lankan woman had a hump-nosed viper bite with no evidence of systemic envenoming during initial hospital stay. Five days later she presented with bite site cellulitis with hemorrhagic blisters, acute kidney injury, and evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia with normal coagulation studies. She was managed with supportive care that included intravenously administered antibiotics, blood transfusions, and hemodialysis; both her microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia improved without any specific intervention. On day 10 she developed: a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction complicated with acute left ventricular failure evidenced by acute shortness of breath with desaturation despite adequate ultrafiltration; new onset lateral lead T inversions in electrocardiogram; raised troponin I titer; and hypokinetic segments on echocardiogram. She was managed with low molecular weight heparin and antiplatelet drugs, which were later discontinued due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Her hospital stay was further complicated by hospital- acquired pneumonia and deep vein thrombosis involving her ileofemoral vein. -

Table S3.1. Habitat Use of Sampled Snakes. Taxonomic Nomenclature

Table S3.1. Habitat use of sampled snakes. Taxonomic nomenclature follows the current classification indexed in the Reptile Database ( http://www.reptile-database.org/ ). For some species, references may reflect outdated taxonomic status. Individual species are coded for habitat association according to Table 3.1. References for this table are listed below. Habitat use for species without a reference were inferred from sister taxa. Broad Habitat Specific Habit Species Association Association References Acanthophis antarcticus Semifossorial Terrestrial-Fossorial Cogger, 2014 Acanthophis laevis Semifossorial Terrestrial-Fossorial O'Shea, 1996 Acanthophis praelongus Semifossorial Terrestrial-Fossorial Cogger, 2014 Acanthophis pyrrhus Semifossorial Terrestrial-Fossorial Cogger, 2014 Acanthophis rugosus Semifossorial Terrestrial-Fossorial Cogger, 2014 Acanthophis wellsi Semifossorial Terrestrial-Fossorial Cogger, 2014 Achalinus meiguensis Semifossorial Subterranean-Debris Wang et al., 2009 Achalinus rufescens Semifossorial Subterranean-Debris Das, 2010 Acrantophis dumerili Terrestrial Terrestrial Andreone & Luiselli, 2000 Acrantophis madagascariensis Terrestrial Terrestrial Andreone & Luiselli, 2000 Acrochordus arafurae Aquatic-Mixed Intertidal Murphy, 2012 Acrochordus granulatus Aquatic-Mixed Intertidal Lang & Vogel, 2005 Acrochordus javanicus Aquatic-Mixed Intertidal Lang & Vogel, 2005 Acutotyphlops kunuaensis Fossorial Subterranean-Burrower Hedges et al., 2014 Acutotyphlops subocularis Fossorial Subterranean-Burrower Hedges et al., 2014 -

2007 Red List of Threatened Fauna and Flora of Sri Lanka

The 2007 Red List of Threatened Fauna and Flora of Sri Lanka This publication has been jointly prepared by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) in Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources. The preparation and printing of this document was carried out with the financial assistance of the Protected Area Management and Wildlife Conservation Project and Royal Netherlands Embassy in Sri Lanka. i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources. This publication has been jointly prepared by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources. The preparation and publication of this document was undertaken with financial assistance from the Protected Area Management and Wildlife Conservation Project and the Royal Netherlands Government. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Copyright: © 2007, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Sri Lanka. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged.