The Conceptual Change of Conscience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternate History – Alternate Memory: Counterfactual Literature in the Context of German Normalization

ALTERNATE HISTORY – ALTERNATE MEMORY: COUNTERFACTUAL LITERATURE IN THE CONTEXT OF GERMAN NORMALIZATION by GUIDO SCHENKEL M.A., Freie Universität Berlin, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (German Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2012 © Guido Schenkel, 2012 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines a variety of Alternate Histories of the Third Reich from the perspective of memory theory. The term ‘Alternate History’ describes a genre of literature that presents fictional accounts of historical developments which deviate from the known course of hi story. These allohistorical narratives are inherently presentist, meaning that their central question of “What If?” can harness the repertoire of collective memory in order to act as both a reflection of and a commentary on contemporary social and political conditions. Moreover, Alternate Histories can act as a form of counter-memory insofar as the counterfactual mode can be used to highlight marginalized historical events. This study investigates a specific manifestation of this process. Contrasted with American and British examples, the primary focus is the analysis of the discursive functions of German-language counterfactual literature in the context of German normalization. The category of normalization connects a variety of commemorative trends in postwar Germany aimed at overcoming the legacy of National Socialism and re-formulating a positive German national identity. The central hypothesis is that Alternate Histories can perform a unique task in this particular discursive setting. In the context of German normalization, counterfactual stories of the history of the Third Reich are capable of functioning as alternate memories, meaning that they effectively replace the memory of real events with fantasies that are better suited to serve as exculpatory narratives for the German collective. -

Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School April 2021 Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis William A. B. Parkhurst University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Parkhurst, William A. B., "Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis by William A. B. Parkhurst A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Lee Braver, Ph.D. Vanessa Lemm, Ph.D. Alex Levine, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 16th, 2021 Keywords: Fredrich Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, History of Philosophy, Continental Philosophy Copyright © 2021, William A. B. Parkhurst Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my mother, Carol Hyatt Parkhurst (RIP), who always believed in my education even when I did not. I am also deeply grateful for the support of my father, Peter Parkhurst, whose support in varying avenues of life was unwavering. I am also deeply grateful to April Dawn Smith. It was only with her help wandering around library basements that I first found genetic forms of diplomatic transcription. -

Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Knut Kristian Langva Døscher German Reprisals in Norway During the Second World War Master’s thesis in Historie Supervisor: Jonas Scherner Trondheim, May 2017 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Preface and acknowledgements The process for finding the topic I wanted to write about for my master's thesis was a long one. It began with narrowing down my wide field of interests to the Norwegian resistance movement. This was done through several discussions with professors at the historical institute of NTNU. Via further discussions with Frode Færøy, associate professor at The Norwegian Home Front Museum, I got it narrowed down to reprisals, and the cases and questions this thesis tackles. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Scherner, for his guidance throughout the process of writing my thesis. I wish also to thank Frode Færøy, Ivar Kraglund and the other helpful people at the Norwegian Home Front Museum for their help in seeking out previous research and sources, and providing opportunity to discuss my findings. I would like to thank my mother, Gunvor, for her good help in reading through the thesis, helping me spot repetitions, and providing a helpful discussion partner. Thanks go also to my girlfriend, Sigrid, for being supportive during the entire process, and especially towards the end. I would also like to thank her for her help with form and syntax. I would like to thank Joachim Rønneberg, for helping me establish the source of some of the information regarding the aftermath of the heavy water raid. I also thank Berit Nøkleby for her help with making sense of some contradictory claims by various sources. -

Legal Naturalism Is a Disjunctivism Roderick T. Long Legal Positivists

Legal Naturalism Is a Disjunctivism Roderick T. Long Auburn University aaeblog.com | [email protected] Abstract: Legal naturalism is the doctrine that a rule’s status as law depends on its moral content; or, in its strongest form, that “an unjust law is not a law.” By drawing an analogy between legal naturalism and perceptual disjunctivism, I argue that this doctrine is more defensible than is generally thought, and in particular that it entails no conflict with ordinary usage. Legal positivists hold that a rule’s status as law never depends on its moral content. In Austin’s famous formulation: “The existence of law is one thing; its merit or demerit is another. Whether a law be is one enquiry; whether it ought to be, or whether it agree with a given or assumed test, is another and different inquiry.”1 There seems to be no generally accepted term for the opposed view, that a rule’s status as law does (sometimes or always) depend on its moral content. Legal moralism would be the natural choice, but that name is already taken to mean the view that the law should impose social standards of morality on private conduct. Legal normativisim, another natural choice, is, somewhat perversely, already in use to denote a species of legal positivism.2 The position in question is sometimes referred to as “the natural law view,” but this is not really accurate; although the view has been held by many natural law theorists, it has not been held by all of them, and is not strictly implied by the natural law position. -

Philosophy of International Law H

Anthony Carty is Professor of Public Law at the Philosophy of University of Aberdeen. P Philosophy of International Law h i ANTHONY CARTY l o s A fundamental challenge to the foundations o International Law of the discipline of international law. p This book offers an internal critique of the h discipline of international law whilst showing y the necessary place for philosophy within this o ANTHONY CARTY subject area. By reintroducing philosophy into f the heart of the study of international law, I Anthony Carty explains how traditionally n philosophy has always been an integral part of t the discipline. However, this has been driven e out by legal positivism, which has, in turn, r n become a pure technique of law. He explores the extent of the disintegration and confusion a in the discipline and offers various ways of t i renewing philosophical practice. o n A range of approaches are covered – post- Jacket design: River Design, Edinburgh a structuralism, neo-Marxist geopolitics, social- Jacket image: Kurt Hutton/Hulton Archive/ l democratic constitutional theory and Getty Images L existential phenomenology – encouraging the Shawcross at the Hague Court in 1948: ‘[ . ] a reader to think afresh about how far to bring Parties to litigation are not entitled to use w order to, or find order in, contemporary merely those documents which they think will international society. assist their case and to suppress others which Key Features are inimical to it. [ . ] As it is, we retain great A misgivings about the propriety of what is being N • Offers a broad survey of possible done, which we can only justify on the T philosophical approaches to international principle “my country [ . -

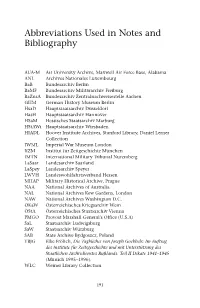

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

CURRICULUM VITAE July 2007

CURRICULUM VITAE January 2013 FRANK CUNNINGHAM Date of Birth: 5 August, 1940. Cities Centre 130 Carlton St. University of Toronto unit 905 455 Spadina Ave. Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario Canada M5A 4K3 Canada M5S 2G8 416-962-9788 416-978-5590 E-mail: [email protected] web: http://individual.utoronto.ca/frankcunningham ACADEMIC HISTORY Ph.D. University of Toronto 1970 M.A. University of Chicago 1965 B.A. Indiana University 1962 University of Toronto Appointments Philosophy Department: Lecturer 1967; Assistant Professor, 1970; Associate Professor, 1974; Professor, 1986. Department of Political Science: Cross Appointment, 2000. Associate Instructor of History and Philosophy of Education, OISE, University of Toronto, 2007 - . Cities Centre, University of Toronto, 2007 - . Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and Political Science, University of Toronto, 2009 - . Visiting Positions University of Amsterdam, Fall 1990 Lanzhou University (PRC), Spring, 199l Ritsumeikan University (Kyoto), Fall 1994, Fall 1997, Spring 2007 University of Rome (I), Spring 1999 Posts Interim Director, Centre for Ethics, University of Toronto, 2011. Principal, Innis College, University of Toronto, 2000- 2005 President, Canadian Philosophical Association, 1997-98 (Vice President, 1996-97) Chair, Department of Philosophy, University of Toronto, 1982- 88 (Associate Chair, 1977-8; Acting Chair, 1991-92) HONOURS Recipient, SAC/APUS Undergraduate Teaching Award, 2005 Recipient, Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal, 2002 Senior Fellow, Massey College, University of Toronto, 1999 - Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, 1995 - Faculty Teaching Fellow, University of Toronto, 1974-75 Mary Beatty Fellowship, University of Toronto, 1965-66 School of Letters Fellowship, Indiana University, 1964-5 Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, 1962-63 Phi Beta Kappa, 1962 Ford Foundation Fellowship, 1961-62 2 TEACHING Introductory Courses: Introduction to Philosophy, Political Philosophy, Science and Society (in the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering), Environmental Ethics. -

2018 • Vol. 2 • No. 2

THE JOURNAL OF REGIONAL HISTORY The world of the historian: ‘The 70th anniversary of Boris Petelin’ Online scientific journal 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 Cherepovets 2018 Publication: 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 JUNE. Issued four times a year. FOUNDER: Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education ‘Cherepovets State University’ The mass media registration certificate is issued by the Federal Service for Supervi- sion of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor). Эл №ФС77-70013 dated 31.05.2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: O.Y. Solodyankina, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) DEPUTY EDITORS-IN-CHIEF: A.N. Egorov, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) E.A. Markov, Doctor of Political Sciences (Cherepovets State University) B.V. Petelin, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) A.L. Kuzminykh, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Vologda Institute of Law and Economics, Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia) EDITOR: N.G. MELNIKOVA COMPUTER DESIGN LAYOUT: M.N. AVDYUKHOVA EXECUTIVE EDITOR: N.A. TIKHOMIROVA (8202) 51-72-40 PROOFREADER (ENGLISH): N. KONEVA, PhD, MITI, DPSI, SFHEA (King’s College London, UK) Address of the publisher, editorial office and printing-office: 162600 Russia, Vologda region, Cherepovets, Prospekt Lunacharskogo, 5. OPEN PRICE ISSN 2587-8352 Online media 12 standard published sheets Publication: 15.06.2018 © Federal State Budgetary Educational 1 Format 60 84 /8. Institution of Higher Education Font style Times. ‘Cherepovets State University’, 2018 Contents Strelets М. B.V. Petelin: Scientist, educator and citizen ............................................ 4 RESEARCH Evdokimova Т. Walter Rathenau – a man ahead of time ............................................ 14 Ermakov A. ‘A blood czar of Franconia’: Gauleiter Julius Streicher ...................... -

Download File

In the Shadow of the Family Tree: Narrating Family History in Väterliteratur and the Generationenromane Jennifer S. Cameron Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 2012 Jennifer S. Cameron All rights reserved ABSTRACT In the Shadow of the Family Tree: Narrating Family History in Väterliteratur and the Generationenromane Jennifer S. Cameron While debates over the memory and representation of the National Socialist past have dominated public discourse in Germany over the last forty years, the literary scene has been the site of experimentation with the genre of the autobiography, as authors developed new strategies for exploring their own relationship to the past through narrative. Since the late 1970s, this experimentation has yielded a series of autobiographical novels which focus not only on the authors’ own lives, but on the lives and experiences of their family members, particularly those who lived during the NS era. In this dissertation, I examine the relationship between two waves of this autobiographical writing, the Väterliteratur novels of the late 1970s and 1980s in the BRD, and the current trend of multi-generational family narratives which began in the late 1990s. In a prelude and three chapters, this dissertation traces the trajectory from Väterliteratur to the Generationenromane through readings of Bernward Vesper’s Die Reise (1977), Christoph Meckel’s Suchbild. Über meinen Vater (1980), Ruth Rehmann’s Der Mann auf der Kanzel (1979), Uwe Timm’s Am Beispiel meines Bruders (2003), Stephan Wackwitz’s Ein unsichtbares Land (2003), Monika Maron’s Pawels Briefe (1999), and Barbara Honigmann’s Ein Kapitel aus meinem Leben (2004). -

Political Theology and Secularization Theory in Germany, 1918-1939: Emanuel Hirsch As a Phenomenon of His Time

Harvard Divinity School Political Theology and Secularization Theory in Germany, 1918-1939: Emanuel Hirsch as a Phenomenon of His Time Author(s): John Stroup Source: The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 80, No. 3 (Jul., 1987), pp. 321-368 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Harvard Divinity School Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1509576 . Accessed: 18/11/2013 17:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and Harvard Divinity School are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Harvard Theological Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.42.202.150 on Mon, 18 Nov 2013 17:40:09 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions HTR80:3 (1987) 321 -68 POLITICAL THEOLOGY AND SECULARIZATION THEORY IN GERMANY, 1918-1939: EMANUEL HIRSCH AS A PHENOMENON OF HIS TIME * John Stroup Yale Divinity School According to Goethe, "writing history is a way of getting the past off your back." In the twentieth century, Protestant theology has a heavy burden on its back-the readiness of some of its most distinguished representatives to embrace totalitarian regimes, notably Adolf Hitler's "Third Reich." In this matter the historian's task is not to jettison but to ensure that the burden on Prot- estants is not too lightly cast aside-an easy temptation if we imagine that the theologians who turned to Hitler did so with the express desire of embracing a monster. -

Gilbert Molinier Lorsqu'alain Badiou Se Fait Historien : Heidegger, La

Texto ! Textes et cultures, vol. XXIV, n°3 (2019) Gilbert Molinier Lorsqu’Alain Badiou se fait historien : Heidegger, la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, et coetera « [L]e spectacle que m’a offert l’université a contribué à m’exorciser complètement, à me délivrer d’une catharsis qui s’est achevée à la Sorbonne quand j’ai vu mes collègues, tous ces singes qui lisaient Heidegger et le citaient en allemand. »1 Vladimir Jankélévitch Résumé. — Cette étude traite d’une dénégation collective. Situant ses recherches au niveau et dans la lignée des prestigieux penseurs de la question de l’Être, Parménide, Aristote, Malebranche…, Alain Badiou rencontre Martin Heidegger. Or, celui-ci est soupçonné d’avoir été et/ou d’avoir toujours été un nazi inconditionnel. Souhaitant effacer une telle tache, Alain Badiou affirme, d’une part : « [Il] n’y a absolument pas besoin de chercher dans sa philosophie des preuves qu’il était nazi, puisqu’il était nazi, voilà ! […] » ; d’autre part et en même temps, il infirme : « C’est bien plutôt dans ce qu’il a fait, ce qu’il a dit, etc. » Cet « etc. » contient donc « ce qu’il a pensé, ce qu’il a écrit » . C’est sur une telle dénégation collective que s’appuient encore l’enseignement et la recherche universitaires dans de nombreux pays, en particulier en France. Or, une dénégation si marquée ne va pas sans produire des effets négatifs. Resümee. — Ursprung der folgenden Bemerkungen ist eine kollektive Verneinung. Alain Badiou, der es liebt, seine Forschungen auf die Ebene und in Übereinstimmung mit den angesehenen Denkern zur Frage des Seins, Parménides, Aristoteles, Malebranche… zu stellen, trifft einen gewissen Martin Heidegger. -

Émigré Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Cognitive Scientists in North America Since the Second World War

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2018 PREPRINT 490 Frank W. Stahnisch (Ed.) Émigré Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Cognitive Scientists in North America since the Second World War Dieses Preprint ist in einer überarbeiteten Form zur Publikation angenommen in: History of Intellectual Culture, Band 12/1 (2017–18): https://www.ucalgary.ca/hic/issues. Accessed 5 July 2018. [Themenheft 2017–18: Émigré Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Cognitive Scientists in North America since the Second World War, Guest Editor: Frank W. Stahnisch]. Der vorliegende Preprint erscheint mit freundlicher Erlaubnis des geschäftsführenden Herausgebers, Herrn Professor Paul J. Stortz an der Universität von Calgary, Alberta, in Kanada. Frank W. Stahnisch e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Émigré Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Cognitive Scientists in North America since WWII Émigré Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Cognitive Scientists in North America since the Second World War Frank W. Stahnisch (Guest Editor)1 Abstract: The processes of long-term migration of physicians and scholars affect both the academic migrants and their receiving environments in often dramatic ways. On the one side, their encounter confronts two different knowledge traditions and personal values. On the other side, migrating scientists and academics are also confronted with foreign institutional, political, economic, and cultural frameworks when trying to establish their own ways of professional knowledge and cultural adjustments. The twentieth century has been called the century of war and forced migration: it witnessed two devastating World Wars, which led to an exodus of physicians, scientists, and academics. Nazism and Fascism in the 1930s and 1940s, forced thousands of scientists and physicians away from their home institutions based in Central and Eastern Europe.