The Lost Mirjaniya Madrasa of Baghdad: Reconstructions and Additional Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Summer 2003), pp. 128-149 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.128 . Accessed: 25/03/2015 15:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Institute for Palestine Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Palestine Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 66.134.128.11 on Wed, 25 Mar 2015 15:58:14 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions QUARTERLY UPDATE ON CONFLICT AND DIPLOMACY 16 FEBRUARY–15 MAY 2003 COMPILED BY MICHELE K. ESPOSITO The Quarte rlyUp date is asummaryofbilate ral, multilate ral, regional,andinte rnationa l events affecting th ePalestinians andth efutureofth epeaceprocess. BILATERALS 29foreign nationals had beenkilled since 9/28/00. PALESTINE-ISRAEL Positioningf orWaronIraq Atthe opening of thequarter, Ariel Tokeep up the appearance of Sharon had beenreelected PM of Israel movementon thepeace process in the and was in theprocess of forming a run-up toawar on Iraq, theQuartet government.U.S. -

A Sufi Reading of Jesus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Representations of Jesus in Islamic Mysticism: Defining the „Sufi Jesus‟ Milad Milani Created from the wine of love, Only love remains when I die. (Rumi)1 I‟ve seen a world without a trace of death, All atoms here have Jesus‟ pure breath. (Rumi)2 Introduction This article examines the limits touched by one religious tradition (Islam) in its particular approach to an important symbolic structure within another religious tradition (Christianity), examining how such a relationship on the peripheries of both these faiths can be better apprehended. At the heart of this discourse is the thematic of love. Indeed, the Qur’an and other Islamic materials do not readily yield an explicit reference to love in the way that such a notion is found within Christianity and the figure of Jesus. This is not to say that „love‟ is altogether absent from Islamic religion, since every Qur‟anic chapter, except for the ninth (surat at-tawbah), is prefaced In the Name of God; the Merciful, the Most Kind (bismillahi r-rahmani r-rahim). Love (Arabic habb; Persian Ishq), however, becomes a foremost concern of Muslim mystics, who from the ninth century onward adopted the theme to convey their experience of longing for God. Sufi references to the theme of love starts with Rabia al-Adawiyya (717-801) and expand outward from there in a powerful tradition. Although not always synonymous with the figure of Jesus, this tradition does, in due course, find a distinct compatibility with him. -

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

Investigating the Patterns of Islamic Architecture in Architecture Design of Third Millennium Mosques

European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences 2014; www.european-science.com Vol.3, No.4 Special Issue on Architecture, Urbanism, and Civil Engineering ISSN 1805-3602 Investigating the Patterns of Islamic Architecture in Architecture Design of Third Millennium Mosques Parvin Farazmand1*, Hassan Satari Sarbangholi2 1Young Researchers and Elite Club, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran; 2Architecture Group of Azad-e-Eslami University, Tabriz Branch *Email: [email protected] Abstract Islamic architecture, which is based on the Islamic school, has been shaped by the total awareness of architects’ of techniques of architecture and adherence to the principles of geometry and inspired by religious beliefs. Principles of geometry and religious beliefs caused certain patterns to take shape in Islamic architecture that were used in designing buildings including mosques. With the advancements in technology, architecture entered a new stage considering the form of construction and the buildings. Islamic architecture and mosque, which is the primary symbol of Islamic architecture, are not different and consequently went through changes in forms and patterns. In this paper, the purpose is to express the place of patterns of Islamic Architecture in the mosques of the third millennium. The method used is descriptive-analytic and the mosques of the third millennium are the statistical population and ten of them are the statistical sample. The tools used are the library studies and the data has been analyzed using chars obtained from Excel. The result indicated that in the architecture of the mosques of the third millennium, the patterns of Islamic architecture have been fixed and proposed, and yet do create different designs that would be novel. -

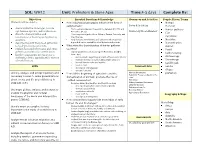

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 Days Complete

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 days Complete By: Objectives Essential Questions & Knowledge Resources and Activities People, Places, Terms Students will be able to: How did physical geography influence the lives of Nomad early humans? Notes & Activities Hominid characterize the stone ages, bronze Homo sapiens emerged in east Africa between 100,000 and Hunter-gatherer age, human species, and civilizations. 400,000 years ago. Prehistory Vocab Handout Clan describe characteristics and Homo sapiens migrated from Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and innovations of hunting and gathering the Americas. Paleolithic societies. Early humans were hunters and gatherers whose survival Neolithic describe the shift from food gathering depended on the availability of wild plants and animals. Domestication to food-producing activities. What were the characteristics of hunter gatherer Artifact explain how and why towns and cities societies? Fossil grew from early human settlements. Hunter-gatherer societies during the Paleolithic Era (Old Carbon dating list the components necessary for a Stone Age) Archaeology civilization while applying their themes o were nomadic, migrating in search of food, water, shelter of world history. o invented the first tools, including simple weapons Stonehenge o learned how to make and use fire Catal hoyuk Skills o lived in clans Internet Links Jericho o developed oral language o created “cave art.” Aleppo Human Organisms Identify, analyze, and interpret primary and How did the beginning of agriculture and the prehistory Paleolithic Era versus Neolithic Era secondary sources to make generalizations domestication of animals promote the rise of chart about events and life in world history to settled communities? Prehistory 1500 A.D. -

Al-Ghazali's Integral Epistemology: a Critical Analysis of the Jewels of the Quran

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2017 Al-Ghazali's integral epistemology: A critical analysis of the jewels of the Quran Amani Mohamed Elshimi Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Elshimi, A. (2017).Al-Ghazali's integral epistemology: A critical analysis of the jewels of the Quran [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/618 MLA Citation Elshimi, Amani Mohamed. Al-Ghazali's integral epistemology: A critical analysis of the jewels of the Quran. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/618 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Humanities and Social Sciences Al-Ghazali’s Integral Epistemology: A Critical Analysis of The Jewels of the Quran A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Amani Elshimi 000-88-0001 under the supervision of Dr. Mohamed Serag Professor of Islamic Studies Thesis readers: Dr. Steffen Stelzer Professor of Philosophy, The American University in Cairo Dr. Aliaa Rafea Professor of Sociology, Ain Shams University; Founder of The Human Foundation NGO May 2017 Acknowledgements First and foremost, Alhamdulillah - my gratitude to God for the knowledge, love, light and faith. -

Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects 2020-03-05 Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco Alyssa Joy Sousa Worcester Polytechnic Institute Brian Preiss Worcester Polytechnic Institute Nathan S. Kaplan Worcester Polytechnic Institute Payton Bielawski Worcester Polytechnic Institute Rebekah Jolin Vernon Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Sousa, A. J., Preiss, B., Kaplan, N. S., Bielawski, P., & Vernon, R. J. (2020). Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/5619 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by Payton S. Bielawski Nathan S. Kaplan Brian C. Preiss Alyssa J. Sousa Rebekah J. Vernon Date: 8 March 2020 Report Submitted to: Mr. Abdelhadi Bennis Association Ribat Al-Fath Professor Laura Roberts Professor Mohammed El Hamzaoui Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate -

Review Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 7, Issue, 03, pp.13547-13558, March, 2015 ISSN: 0975-833X REVIEW ARTICLE CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURAL TRENDS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE SYMBOLIC AND SPIRITUAL FUNCTION OF THE MOSQUE *Aida Hoteit Department of Architecture, Institute of Fine Arts Lebanese University – Beirut, Lebanon ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Since the dawn of history, mosque architecture has witnessed changes and developments to meet the Received 13th December, 2014 cultures and civilizations passing through; accordingly, modern contemporary architectural trends Received in revised form have presented bold innovative solutions that affect the stereotypes that have been attributed to 29th January, 2015 mosques over time. At this point, a discussion was initiated on the feasibility of maintaining certain Accepted 28th February, 2015 mosque elements that are considered to be essential for some in the process of going to the mosque, Published online 17th March, 2015 such as the minaret and the dome. However, some trends posed ideas that exceeded the spiritual function of a mosque, as well as the cause and essence of its existence; accordingly, the present Key words: research study was conducted to elucidate those various trends and to discuss and evaluate their conformity with the standards and principles in mosque architecture. The study begins with the Mosque, definition of a mosque and its fundamental elements, determines the most significant mosque styles in Contemporary mosque, the world while highlighting the relationship each has with the culture or civilization it produced, and Islam, subsequently addresses the function of the mosque and the requirements to be considered in Islamic architecture, compliance with the provisions of Sharia. -

Vernacular Tradition and the Islamic Architecture of Bosra, 1992

1 VERNACULAR TRADITION AND THE ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF BOSRA Ph.D. dissertation The Royal Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture Copenhagen. Flemming Aalund, architect MAA. Copenhagen, April 1991. (revised edition, June 1992) 2 LIST OF CONTENTS : List of maps and drawings......................... 1 List of plates.................................... 4 Preface: Context and purpose .............................. 7 Contents.......................................... 8 Previous research................................. 9 Acknowledgements.................................. 11 PART I: THE PHYSICAL AND HISTORIC SETTING The geographical setting.......................... 13 Development of historic townscape and buildings... 16 The Islamic town.................................. 19 The Islamic renaissance........................... 21 PART II: THE VERNACULAR BUILDING TRADITION Introduction...................................... 27 Casestudies: - Umm az-Zetun.................................... 29 - Mu'arribeh...................................... 30 - Djemmerin....................................... 30 - Inkhil.......................................... 32 General features: - The walling: construction and materials......... 34 - The roofing..................................... 35 - The plan and structural form.................... 37 - The sectional form: the iwan.................... 38 - The plan form: the bayt......................... 39 conclusion........................................ 40 PART III: CATALOGUE OF ISLAMIC MONUMENTS IN BOSRA Introduction..................................... -

Islam in Europe

The Way, 41.2 (2001), 122-135. www.theway.org.uk 122 Islam in Europe Anthony O'Mahony SLAM PRESENTS TWO DISTINCT FACES to Europe, the one a threat, the I other that of an itinerant culture. However viewed, the history of the relationship between Islam and Europe is problematic and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. The relationship between Christians and Muslims over the centuries has been long and tortuous. Geographically the origins of the two communities are not so far apart - Bethlehem and Jerusalem are only some eight hundred miles from Mecca. But as the two communities have grown and become universal rather than local, the relationship between them has changed - sometimes downright enmity, sometimes rivalry and competition, sometimes co-operation and collaboration. Different regions of the world in different centuries have therefore witnessed a whole range of encounters between Christians and Muslims. The historical study of the relationship is still in its begin- nings. It cannot be otherwise, since Islamic history, as well as the history of those Christian communities that have been in contact with Islam, is still being written. Obviously Christian-Muslim relations do not exist in a vacuum. The two worlds have known violent confrontation: Muslim conquests of Christian parts of the world; the Crusades still vividly remembered today; the expansion of the Turkish Ottoman Empire; the Armenian massacres and genocide; European colonialism of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; the rise of Christian missions; the continuing difficult situations in which Christians find themselves in dominant Muslim societies, such as Sudan, Indonesia, Pakistan. -

Two Queens of ^Baghdad Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Two Queens of ^Baghdad oi.uchicago.edu Courtesy of Dr. Erich Schmidt TOMB OF ZUBAIDAH oi.uchicago.edu Two Queens of Baghdad MOTHER AND WIFE OF HARUN AL-RASH I D By NABIA ABBOTT ti Vita 0CCO' cniia latur THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu The University of Chicago Press • Chicago 37 Agent: Cambridge University Press • London Copyright 1946 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1946. Composed and printed by The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu Preface HE historical and legendary fame of Harun al- Rashld, the most renowned of the caliphs of Bagh dad and hero of many an Arabian Nights' tale, has ren dered him for centuries a potent attraction for his torians, biographers, and litterateurs. Early Moslem historians recognized a measure of political influence exerted on him by his mother Khaizuran and by his wife Zubaidah. His more recent biographers have tended either to exaggerate or to underestimate the role of these royal women, and all have treated them more or less summarily. It seemed, therefore, desirable to break fresh ground in an effort to uncover all the pertinent his torical materials on the two queens themselves, in order the better to understand and estimate the nature and the extent of their influence on Harun and on several others of the early cAbbasid caliphs. As the work progressed, first Khaizuran and then Zubaidah emerged from the privacy of the royal harem to the center of the stage of early cAbbasid history. -

Cairo 1993/94, Polish-Egyptian Mission for Islamic Architecture, Amir Kebir Qurqumas Project

CAIRO 1993/94, POLISH-EGYPTIAN MISSION FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE, AMIR KEBIR QURQUMAS PROJECT Jarosław Dobrowolski The Mission, organized jointly by the Egyptian Supreme Coun- cil of Antiquities and the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of Warsaw University, works on a constant basis. The following report covers the period from October 1, 1993, to December 31, 1994.1 RESTORATION WORK RESIDENTIAL PART (arawaqa or khanqa) Following a study of the technical conditions of this build- ing in November 1993, it was decided to take immediate action in the seriously endangered structure. First, emergency reinforce- ment of the existing walls was done by filling in voids in the 1 The Polish members of the Mission were: Mr. Jarosław Dobrowolski (head of the Mission), Mrs. Agnieszka Dobrowolska, architects, year-round members; Dr. Grzegorz Bogobowicz, structural engineer, 1 October-1 December 1993; and Mr. Paweł Jackowski, sculptor-restorer, 1 February-28 April 1994. The SCA was repre- sented at the site by Mrs. Mervet Saad Mahmud, Chief Inspector, for whom highest credits are due for her extremely effective and involved work. In December 1994 she was replaced by Mr. Mohammad Othman and Mrs. Fatim Hasan, inspectors. They were aided by Mrs. Badriya Mohammad, inspector, and by engineers Mr. Tariq Bah- gat and later Mr. Wahid Barbari. The Mission acted under the general supervision of Mr. Medhad Husein al-Minnabawi, General Director, Foreign Missions Department, Islamic and Coptic Sector, whose personal involvement was of great importance for our work. The Mission's work was possible thanks to friendly cooperation and concern of the SCA authorities at all levels.