Property Concept Words in Six Amazonian Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 1 Volume 11, Issue 1 6-2013 The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin Andrés Pablo Salanova University of Ottawa Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Epps, Patience and Salanova, Andrés Pablo (2013). "The Languages of Amazonia," Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 1, 1-28. Available at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epps and Salanova: The Languages of Amazonia ARTICLE The Languages of Amazonia Patience Epps University of Texas at Austin Andrés Pablo Salanova University of Ottawa Introduction Amazonia is a linguistic treasure-trove. In this region, defined roughly as the area of the Amazon and Orinoco basins, the diversity of languages is immense, with some 300 indigenous languages corresponding to over 50 distinct ‘genealogical’ units (see Rodrigues 2000) – language families or language isolates for which no relationship to any other has yet been conclusively demonstrated; as distinct, for example, as Japanese and Spanish, or German and Basque (see section 12 below). Yet our knowledge of these languages has long been minimal, so much so that the region was described only a decade ago as a “linguistic black box" (Grinevald 1998:127). -

Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action

Available online at: http://lumenpublishing.com/proceedings/published-volumes/lumen- proceedings/rsacvp2017/ 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN* https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 How to cite: Roman, D.-M. (2017). The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language. In C. Ignatescu, A. Sandu, & T. Ciulei (eds.), Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice (pp.682-694). Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN1* Abstract This study is the outcome of research on the grammar of the contemporary Romanian language. It proposes a discussion of the marked nominalization of adjectives in Romanian, the analysis being focused on the hypostases of the convertor (nominalizer). Within this area of research, contemporary scholarly treaties have so far accepted solely nominalizers of the determinative article type (definite and indefinite) and nominalizers of the vocative desinence type, in the singular. However, with regard to the marked conversion of an adjective to the large class of nouns, the phenomenon of enclitic articulation does not always also entail the individualization of the nominalized adjective, as an expression of the category of definite determination. -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

Possessive Agreement Turned Into a Derivational Suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1

Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1. Introduction The prototypical case of grammaticalization is a process in the course of which a lexical word loses its descriptive content and becomes a grammatical marker. This paper discusses a more complex type of grammaticalization, in the course of which an agreement suffix marking the presence of a phonologically null pronominal possessor is reanalyzed as a derivational suffix marking specificity, whereby the pro cross-referenced by it is lost. The phenomenon in question is known from various Uralic languages, where possessive agreement appears to have assumed a determiner-like function. It has recently been a much discussed question how the possessive and non-possessive uses of the agreement suffixes relate to each other (Nikolaeva 2003); whether Uralic definiteness-marking possessive agreement has been grammaticalized into a definite determiner (Gerland 2014), or it has preserved its original possessive function, merely the possessor–possessum relation is looser in Uralic than in the Indo-Europen languages, encompassing all kinds of associative relations (Fraurud 2001). The hypothesis has also been raised that in the Uralic languages, possessive agreement plays a role in organizing discourse, i.e., in linking participants into a topic chain (Janda 2015). This paper helps to clarify these issues by reconstructing the grammaticalization of possessive agreement into a partitivity marker in Hungarian, the language with the longest documented history in the Uralic family. Hungarian has two possessive morphemes functioning as a partitivity marker: -ik, an obsolete allomorph of the 3rd person plural possessive suffix, and -(j)A, the productive 3rd person singular possessive suffix. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/42006 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. Kwaza in a Comparative Perspective Author(s): Hein van der Voort Reviewed work(s): Source: International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol. 71, No. 4 (October 2005), pp. 365- 412 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/501245 . Accessed: 13/07/2012 09:37 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of American Linguistics. http://www.jstor.org KWAZA IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE1 Hein van der Voort Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi In view of the previous sparsity of data, the existing claims with regard to a genea- logical classification of the Aikanã, Kanoê, and Kwaza languages of Rondônia, on the Brazilian side of the Guaporé River, are premature and unconvincing. -

Inalienable Possession in Swedish and Danish – a Diachronic Perspective 27

FOLIA SCANDINAVICA VOL. 23 POZNAŃ 20 17 DOI: 10.1515/fsp - 2017 - 000 5 INALIENABLE POSSESSI ON IN SWEDISH AND DANISH – A DIACHRONIC PERSP ECTIVE 1 A LICJA P IOTROWSKA D OMINIKA S KRZYPEK Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań A BSTRACT . In this paper we discuss the alienability splits in two Mainland Scandinavian language s, Swedish and Danish, in a diachronic context. Although it is not universally acknowledged that such splits exist in modern Scandinavian languages, many nouns typically included in inalienable structures such as kinship terms, body part nouns and nouns de scribing culturally important items show different behaviour from those considered alienable. The differences involve the use of (reflexive) possessive pronouns vs. the definite article, which differentiates the Scandinavian languages from e.g. English. As the definite article is a relatively new arrival in the Scandinavian languages, we look at when the modern pattern could have evolved by a close examination of possessive structures with potential inalienables in Old Swedish and Old Danish. Our results re veal that to begin with, inalienables are usually bare nouns and come to be marked with the definite article in the course of its grammaticalization. 1. INTRODUCTION One of the striking differences between the North Germanic languages Swedish and Danish on the one hand and English on the other is the possibility to use definite forms of nouns without a realized possessive in inalienable possession constructions. Consider the following examples: 1 The work on this paper was funded by the grant Diachrony of article systems in Scandi - navian languages , UMO - 2015/19/B/HS2/00143, from the National Science Centre, Poland. -

'Appositive Possession in Ainu and Around the Pacific'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Appositive possession in Ainu and around the Pacific Bugaeva, Anna ; Nichols, Johanna ; Bickel, Balthasar Abstract: Some languages around the Pacific have multiple possessive classes of alienable constructions using appositive nouns or classifiers. This pattern differs from the most common kind of alienable/i- nalienable distinction, which involves marking, usually affixal, on the possessum, and has only one class of alienables. The Japanese language isolate Ainu has possessive marking that is reminiscent of the Circum-Pacific pattern. It is distinctive, however, in that the possessor is coded not as a dependent in an NP but as an argument in a finite clause, and the appositive word is a verb. This paper givesa first comprehensive, typologically grounded description of Ainu possession and reconstructs the pattern that must have been standard when Ainu was still the daily language of a large speech community; Ainu then had multiple alienable class constructions. We report a cross-linguistic survey expanding pre- vious coverage of the appositive type and show how Ainu fits in. We split alienable/inalienable into two different phenomena: argument structure (with types based on possessibility: optionally possessible, obligatorily possessed, and non-possessible) and valence (alienable, inalienable classes). Valence-changing operations are derived alienability and derived inalienability. Our survey classifies the possessive systems of languages in these terms. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2021-2079 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-204338 Journal Article Published Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. -

Languages of the Middle Andes in Areal-Typological Perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran

Languages of the Middle Andes in areal-typological perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran Willem F.H. Adelaar 1. Introduction1 Among the indigenous languages of the Andean region of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, northern Chile and northern Argentina, Quechuan and Aymaran have traditionally occupied a dominant position. Both Quechuan and Aymaran are language families of several million speakers each. Quechuan consists of a conglomerate of geo- graphically defined varieties, traditionally referred to as Quechua “dialects”, not- withstanding the fact that mutual intelligibility is often lacking. Present-day Ayma- ran consists of two distinct languages that are not normally referred to as “dialects”. The absence of a demonstrable genetic relationship between the Quechuan and Aymaran language families, accompanied by a lack of recognizable external gen- etic connections, suggests a long period of independent development, which may hark back to a period of incipient subsistence agriculture roughly dated between 8000 and 5000 BP (Torero 2002: 123–124), long before the Andean civilization at- tained its highest stages of complexity. Quechuan and Aymaran feature a great amount of detailed structural, phono- logical and lexical similarities and thus exemplify one of the most intriguing and intense cases of language contact to be found in the entire world. Often treated as a product of long-term convergence, the similarities between the Quechuan and Ay- maran families can best be understood as the result of an intense period of social and cultural intertwinement, which must have pre-dated the stage of the proto-lan- guages and was in turn followed by a protracted process of incidental and locally confined diffusion. -

The Pragmatics and Syntax of German Inalienable Possession Constructions University of Georgia1

The Pragmatics and Syntax of German Inalienable Possession Constructions 1 2 VERA LEE-SCHOENFELD , GABRIELE DIEWALD University of Georgia1; Leibniz Universität Hannover2 1 The Phenomenon and Previous Syntactic/Pragmatic Analyses The prototypical inalienable possession construction in German has a dative (DAT)-marked external possessor: (0) Bello hat mir die Hand geleckt. Bello has me.DAT the hand licked ‘Bello licked my hand.’ This is an instance of external possession because the understood possessor of the body part, the possessum, is expressed outside of the nominal phrase containing the possessum, showing up as 1 an object pronoun (mir ‘me.DAT) in the verbal argument domain. Notice that the literal translation of the dative does not work in English. This is because English generally prefers internal possessors and thus makes use of the possessive pronoun my rather than the object pronoun me in examples like (0) (see e.g. Haspelmath 2001, König and Gast 2012). In German inalienable possession constructions with a PP-embedded possessum, there is considerable variation between the prototypical possessor dative construction and four others, so that there are a total of five different construction types: external possession with a dative- marked possessor (1a), external possession with an accusative (ACC)-marked possessor (1b), internal possession, with a genitive (GEN)-marked possessor (2), and doubly-marked possession, with both external and internal possessor, where the external possessor is again either dative- marked (3a) or accusative-marked (3b).2 (1) a. Bello hat mir in die Hand gebissen. Bello has me.DAT in the hand bitten ‘Bello bit me in the hand.’ b. -

External Possession and the Undisentanglability of Syntax and Semantics

External Possession and the Undisentanglability of Syntax and Semantics Luke What is language? (Page 1) The Intuitive View of Language Well, languages are made of sound. And language has meaning. So language is ‘sound with meaning.’ (Aristotle) Saussure’s signifinnt (sound) and signifi (meaning) !ut language is far more than that""" In fact, most of linguistics is the study of the traits of language apart from meaning and sound per se# S!nta$ Phonolog! # Sound and meaning # Phonology # Syntax # $ormal semantics # Mor&hology %dramati&ation' Can I have an orange? inguistics ' the study of the lower iceberg Linguistics generally is the study of what makes us diferent from other apes. )If we want to study the lower iceberg, we ha+e to hold the upper iceberg onstant,- (An assum"tion of Stru tural and .enerati+e Linguisti s,) Traditional Generative Linguistics )techni/ues which enable 0linguists] 0...1 to determine the state and structure of natural languages winthount seminntic reference- (2homsky 1953) )I think that we are for ed to onclude that grammar is autonomous and independent of meaning.” (Chomsky 1957: 17) )*s&ects” Theory of (rammar ,-./01 (from Searle 1368) The Theoretical Problem S!ntax precedes semantics… (Interpreti+e) Primi ficie, shouldn’t the linguistic s!stem know the semantics of a sentence it makes9 Additionall!, the s!nta tic engine has to rule out semanticall! anomalous sentences. Selectional features and Subcat $rames *the *o! ela"sed. ela"se 0;, re/uires 0<tem"oral1 =P1 Why do this when semanti s will alread! >?:?9 an anomalous senten e9 If s!nta$ "re edes semanti s, there is alwa!s redundincy. -

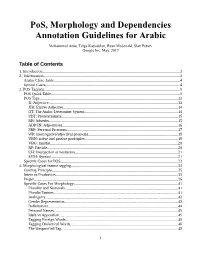

Pos, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic

PoS, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic Mohammed Attia, Tolga Kayadelen, Ryan Mcdonald, Slav Petrov Google Inc. May, 2017 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................2 2. Tokenization...........................................................................................................................................3 Arabic Clitic Table................................................................................................................................4 Special Cases.........................................................................................................................................4 3. POS Tagging..........................................................................................................................................8 POS Quick Table...................................................................................................................................8 POS Tags.............................................................................................................................................13 JJ: Adjective....................................................................................................................................13 JJR: Elative Adjective.....................................................................................................................14 DT: The Arabic Determiner System...............................................................................................14