Jernej Weiss 'CZECH-SLOVENE' MUSICIANS? on the QUESTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

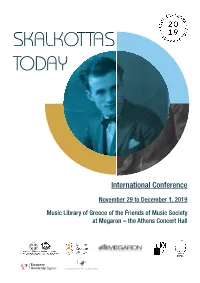

SKALKOTTAS Program 148X21

International Conference Program NOVEMBER 29 TO DECEMBER 1, 2019 Music Library of Greece of the Friends of Music Society at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall Organised by the Music Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of the Friends of Music Society, Megaron—The Athens Concert Hall, Athens State Orchestra, Greek Composer’s Union, Foundation of Emilios Chourmouzios—Marika Papaioannou, and European University of Cyprus. With the support of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Directorate of Modern Cultural Heritage The conference is held under the auspices of the International Musicological Society (IMS) and the Hellenic Musicological Society It is with great pleasure and anticipa- compositional technique. This confer- tion that this conference is taking place ence will give a chance to musicolo- Organizing Committee: Foreword .................................... 3 in the context of “2019 - Skalkottas gists and musicians to present their Thanassis Apostolopoulos Year”. The conference is dedicated to research on Skalkottas and his environ- the life and works of Nikos Skalkottas ment. It is also happening Today, one Alexandros Charkiolakis Schedule .................................... 4 (1904-1949), one of the most important year after the Aimilios Chourmouzios- Titos Gouvelis Greek composers of the twentieth cen- Marika Papaioannou Foundation depos- tury, on the occasion of the 70th anni- ited the composer’s archive at the Music Petros Fragistas Abstracts .................................... 9 versary of his death and the deposition Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of Vera Kriezi of his Archive at the Music Library of The Friends of Music Society to keep Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of The Friends safe, document and make it available for Martin Krithara Biographies ............................. -

In Loving Memory of Milan Yaklich Dennis & Janice Strootman UWM Foundation Non-Profit Slovenian Arts Program Organization 1440 East North Avenue U.S

FALL ISSUE: NOVEMBER 2019 EDITOR: HELEN E. FROHNA NEWSLETTER OF THE UWM SLOVENIAN ARTS COUNCIL SLOVENIAN ARTS PROGRAM How would you describe Slovenian music? President: Christina Carroll Would it be Frankie Yankovic playing his accordion and singing about you and me under the silk umbrella (Židana Marela Polka)? Or would it be the Original Oberkrainer (Ansambel Avsenik) performing Trompetenecho? This is the type of music that most Slovenian-Americans recognize and relate to. When people left their homes and families behind in Slovenia/Austrian Empire to come to America to reinvent their lives in the mines and factories in Michigan’s UP, the Iron Range in Minnesota, and the cities of Cleveland, Chicago, and Milwaukee, they wanted to remember a little bit of “home”. Various singing choirs and musicians organized to replicate the melodies and sounds that they knew when they were growing up. Folk melodies were what they remembered. Over the past 30 years, the UWM Slovenian Arts Council presented various music programs that featured Slovenian performers and/or Slovenian compositions. Not all performers were from Slovenia, not all music sounded like familiar Slovenian folk tunes. Our goal was to showcase various types of music for the enjoyment and enrichment of the Slovenian-American commu- nity and the public at large. Singers and musicians from Slovenia consisted of the Deseti Brat Oktet, Navihanke, Vlado Kreslin, Perpetuum Jazzile, Slovenski Oktet, and the Lojze Slak Ansambel, performing folk, classical, and contemporary compositions. But other programs also featured the Singing Slovenes from Minnesota; from Cleveland, the Jeff Pecon Band, Fantje Na Vasi, and the Fantje’s next generation singers, Mi Smo Mi. -

Real Estate Newsletter with Articles (Traditional, 2

Nationality Rooms Newsletter Nationality Rooms and Intercultural Exchange Programs at the University of Pittsburgh http://www.nationalityrooms.pitt.edu/news-events Volume Fall 2017 THE SCOTTISH NATIONALITY ROOM Dedicated July 8, 1938 THE SCOTTISH NATIONALITY ROOM E. Maxine Bruhns The dignity of a great hall bearing tributes to creative men, ancient clans, edu- cation, and the nobility of freedom is felt in the Scottish Nationality Room. The oak doors are adapted from the entrance to Rowallan Castle in Ayrshire. Above the doors and cabinet are lines lauding freedom from The Brus by John Barbour . On either side of the sandstone fireplace are matching kists, or chests. A portrait of Scotland’s immortal poet, Robert Burns, dominates above the mantel. Above the portrait is the cross of St. Andrew, Scotland’s patron saint. Bronze figures representing 13th– and 14th-century patriots William Wallace and Robert the Bruce stand on the mantel near an arrangement of dried heather. The blackboard trim bears a proverb found over a door in 1576: “Gif Ye did as ye should Ye might haif as Ye would.” Names of famous Scots are carved on blackboard panels and above the mantel. Student chairs are patterned after one owned by John Knox. An aumbry, or wall closet, pro- vided the inspiration for the display cabinet. The plaster frieze bears symbols of 14 clans Oak Door whose members served on the Room’s committee. The wrought-iron chandelier design was inspired by an iron coronet retrieved from the battlefield at Bannockburn (1314). Bay win- dows, emblazoned with stained-glass coats of arms, represent the Univer- sities of Glasgow, St. -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea. -

ARC Music CATALOGUE

WELCOME TO THE ARC Music CATALOGUE Welcome to the latest ARC Music catalogue. Here you will find possibly the finest and largest collection of world & folk music and other related genres in the world. Covering music from Africa to Ireland, from Tahiti to Iceland, from Tierra del Fuego to Yakutia and from Tango, Salsa and Merengue to world music fusion and crossovers to mainstream - our repertoire is huge. Our label was established in 1976 and since then we have built up a considerable library of recordings which document the indig- enous lifestyles and traditions of cultures and peoples from all over the world. We strive to supply you with interesting and pleasing recordings of the highest quality and at the same time providing information about the artists/groups, the instruments and the music they play and any other information we think might interest you. An important note. You will see next to the titles of each album on each page a product number (EUCD then a number). This is our reference number for each album. If you should ever encounter any difficulties obtaining our CDs in record stores please contact us through the appropriate company for your country on the back page of this catalogue - we will help you to get our music. Enjoy the catalogue, please contact us at any time to order and enjoy wonderful music from around the world with ARC Music. Best wishes, the ARC Music team. SPECIAL NOTE Instrumental albums in TOP 10 Best-Selling RELEASES 2007/2008 our catalogue are marked with this symbol: 1. -

NEWSLETTER Lecture by Slavoj Žižek: More Alienation, Please! A

Energy Announcement: List of Diplomacy Consular Hours Upcoming Consultations in San Francisco Events page 3 > page 3 > page 8 - 12 > NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 16, 2015, VOLUME 11, NUMBER 23 Lecture by Slavoj Žižek: More Alienation, Please! A Critique of Cultural Violence. The Embassy of With his address to a Slovenia, together with full NYU auditorium, keynoted the Goethe Institute in “More Alienation, Please! A a leading contemporary thinker Washington, DC and the John Critique of Cultural Violence”, and cultural theorist. The shock Brademas Center for the Slavoj Žižek opened the EUNIC over the terrorist attacks in Paris Study of Congress at New Iconoclash series of transatlantic in January 2015 inspired Žižek York University’s Washington conversations about the to write an essay on Islam and branch, hosted on October 8 ongoing challenges of Islamist modernism. In it, he addressed a lecture by one of Slovenia’s radical fundamentalism and its the rupture between the Western most influential intellectuals: impact related to democracy world’s advocacy for tolerance political philosopher and and universal values of cultural and the fundamental hatred cultural critic Slavoj Žižek. heritage. Žižek writes on a of Western liberalism within Opening remarks were given diverse range of topics, including radical Islam; the same issue he by Ambassador Dr. Božo political theory, theology, and also discussed in his lecture on Cerar, as well as by Goethe psychoanalysis. His lectures Thursday evening. Institute DC Director, Wilfried and appearances around the The event, which was also Eckstein. globe underline his position as streemed live, was moderated Embassy of Slovenia 2410 California Street, NW twitter.com/SLOinUSA Washington, D.C. -

The Dick Crum Collection, Date (Inclusive): 1950-1985 Collection Number: 2007.01 Extent: 42 Boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2r29q890 No online items Finding Aid for the The Dick Crum Collection 1950-1985 Processed by Ethnomusicology Archive Staff. Ethnomusicology Archive UCLA 1630 Schoenberg Music Building Box 951657 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1657 Phone: (310) 825-1695 Fax: (310) 206-4738 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.ethnomusic.ucla.edu/Archive/ ©2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the The Dick Crum 2007.01 1 Collection 1950-1985 Descriptive Summary Title: The Dick Crum Collection, Date (inclusive): 1950-1985 Collection number: 2007.01 Extent: 42 boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Ethnomusicology Archive Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Dick Crum (1928-2005) was a teacher, dancer, and choreographer of European folk music and dance, but his expertise was in Balkan folk culture. Over the course of his lifetime, Crum amassed thousands of European folk music records. The UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive received part of Dick Crum's personal phonograph collection in 2007. This collection consists of more than 1,300 commercially-produced phonograph recordings (LPs, 78s, 45s) primarily from Eastern Europe. Many of these albums are no longer in print, or, are difficult to purchase. More information on Dick Crum can be found in the Winter 2007 edition of the EAR (Ethnomusicology Archive Report), found here: http://www.ethnomusic.ucla.edu/archive/EARvol7no2.html#deposit. Language of Material: Collection materials in English, Croatian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Greek Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S. -

MIDWEST CHAPTER NEWSLETTER Spring, 1991

MUSIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION - MIDWEST CHAPTER NEWSLETTER Spring, 1991 FROM THE CHAIR Greetings! The fall meeting in Milwaukee was exceptional both in the local arrangements and in the program. Our thanks go to Linda Hartig and Lynn Gullikson for the arrangements, and to Beth Christensen for the program. All concerned did an outstanding job. Our Fall 1991 meeting will be in Kansas City, Missouri, October 24-26, hosted by Peter Munstedt and Anna Sylvester, who have promised us some interesting music! More about that in the next Newsletter. In Milwaukee, we said goodbye to two people who have served the Chapter for several years. Beth Christensen concluded her year as Past Chair with her usual flair. She now turns her attention to her next job--chairing the Program Committee for the Music Library Association's Annual Meeting in Baltimore. And with this issue we also say a heartfelt thanks to Joan Falconer, who concludes her tenure as editor of the chapter Newsletter. Jody has done a wonderful job and deserves the rest that she has earned. We greet our new chapter Vice Chair/Chair-Elect Allie Wise Goudy. Some of you may remember when Allie served the Chapter as secretary-treasurer. I know we can look forward with pleasure to Allie's tenure as Chair. Allie will also be serving as program chair for the Kansas City meeting. Many of you will also remember Rick Jones, who chaired the Midwest Chapter several years ago and now succeeds Jody as Newsletter Editor. We welcome these two old/new members to their respective new positions. -

NEWSLETTER Luxury Slovenia Presented at the Ambassador's

Wine Tasting Reception Education: for St. Martin’s for Clemson VTIS Event Day University in New York > page 2 & 3 > page 4 page 7 > NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 27, 2015, VOLUME 11, NUMBER 27 Luxury Slovenia Presented at the Ambassador’s Residence On Monday, November 16, Ambassador Dr. Cerar hosted Following the opening Košir Gažovič. Delicious bites of in his residence a wine tasting address, Imperial Travel’s General traditional Slovenian dishes were event for the Connoisseur’s team Managing Partners Matej Valenčič accompanied by the wine selection of expert travel consultants. In his and Matej Knific presented Luxury which included: Radgonska Srebrna introductory remarks, Ambassador Slovenia as a highly accomplished Penina Sparkling Wine, Chardonnay Dr. Cerar outlined the importance brand which boasts quality, by Sanctum Wines, Batič Rose, of the tourist sector for Slovenian exceptional service and perfect Merlot by Zanut Kocjančič, 360 by economy. He emphasized balance between price and top- House Of Wine Doppler, Bagueri Slovenia’s advantages as a luxury quality luxury. Guests could also get Cabernet Sauvignon, White Pinot destination: its combination of acquainted with the wine regions by Ščurek and Kabaj Pinot Grigio modern infrastructure along with in Slovenia, which also offer a Orange Wine. Ms. Polona Brumec, beautiful and diverse nature variety of options for a unique travel representative of Sanctum Winery, and genuine hospitality, which experience. They also got to try and Ms. Marta Rojnik of the Rojnik provide sophisticated guests with the assortment of Slovenian wines, Hops Brewery were also present at unsurpassed luxury. presented by sommelier Ms. Andreja the wine tasting event. -

24 September 2017 Cankarjev Dom – Ljubljana SLOVENIA

21 – 24 September 2017 Cankarjev dom – Ljubljana SLOVENIA WELCOME to the European Jazz Conference, the most important annual meeting of professionals from the jazz sector in Europe, in particular of presenters, managers, agents and national/regional organisations. The Conference is composed of inspiring keynote speeches, high-level discussion groups and workshops, networking sessions for professionals, cultural visits and in the evenings a showcase programme of the best new artists from the host country, this year Slovenia. #europejazz17 21/09 15:00 OPENING AND WELCOME of EJN Members Kosovel Hall, -2 15:15 Overview of past activities, introduction of workplan 2017-2021 Kosovel Hall, -2 16:00 Coffee break Foyer, -2 16:30 FORMAL EJN GENERAL ASSEMBLY Kosovel Hall, -2 19:00 OPENING GALA CONCERT: Bojan Z & Goran Bojčevski Quartet / Rabih Abou-Khalil trio Linhart Hall, -1 22:30 Events around the city 22/09 10:30 OPENING CEREMONY: welcome addresses Linhart Hall, -2 11:00 KEYNOTE SPEECH: Rabih Abou-Khalil Linhart Hall, -2 12:00 PLENARY DEBATE: Rabih Abou-Khalil, Anuša Pisanec, Mehdi Marechal, N’toko Moderator: Francesco Martinelli Linhart Hall, -2 13:00 Lunch Foyer, -2 14:45 BOOK PRESENTATION: “The Shared Roots of European Jazz” Linhart Hall, -2 15:30 SPECIAL CONCERT: To Pianos - Kaja Draksler & Eve Risser Štih Hall, -1 16:15 CREATIVE WALKS: 6 parallel groups around the city of Ljubljana Ending at Ljubljana Market - “Open kitchen” event 19:30 Dinner at Cankarjev dom Foyer, -2 21:00 SLOVENIA SHOWCASE FESTIVAL #1 CD Club 10:30 KEYNOTE SPEECH: Bojan -

Music Entrepreneurship and Family Businesses: the Case of Avsenik Brothers Ensemble

Preliminary communication Received: 8 September 2014 Accepted: 23 March 2015 DOI: 10.15176/vol52no102 UDK 784.4(497.12) 398.8:67/68](497. -

Kozmus Takes Silver in Hammer

Summer Slovenia Scholarships for Festivals Wine Slovenians in Slovenia Diversity Abroad page 2 5 > page 6 > page 7 > NEWSLETTER AUGUST 10, 2012, VOLUME 8, NUMBER 32 Kozmus Takes Silver in Hammer Slovenian fi eld star Primož Kozmus took the silver in men’s hammer throw at the London Olympics with a throw of 79.36m on Sunday, August Primož Kozmus with his silver medal at the Summer Olympics. 5. The silver completes the full medal set for Slovenia, have allowed him to have a 32yearold confi rmed his status which now has four medals shot at winner Krisztian Pars of as Slovenia’s most successful in London. Hungary, the Olympic champion track and fi eld athlete of all time. Overcoming a below- from Beijing was never in In addition to his Olympic par season, Kozmus once again danger of missing out on the medals, Kozmus also has three confi rmed he was a competitor podium. Third place went to Koji medals (one of each class) who thrives in big competitions, Murofushi of Japan with a throw from World Championships. as he bettered his preOlympic of 78.71 meters. The London silver is Kozmus’s season best by two meters to Kozmus’s silver increases second medal since coming out send Slovenian track and fi eld Slovenia’s medal tally in London of retirement in late 2010, after fans into raptures. to four: one gold, one silver, and winning the bronze at the World While unable to surpass two bronze. Bagging his second Championship in Daegu last the 80m mark, which would piece of Olympic hardware, the year.